Nicolas Flamel (circa 1330 or 1340, possibly in Pontoise – in Paris) was a Parisian bourgeois of the 14th century, a public writer, copyist, and sworn book merchant. His successful career, marriage to Pernelle, a wealthy widow, and real estate speculations ensured him a comfortable fortune, which he dedicated, towards the end of his life, to pious foundations and constructions. This fortune, amplified by rumors, is the origin of the myth that made him an alchemist who succeeded in the quest for the philosopher’s stone, capable of transmuting metals into gold.

Because of this reputation, several alchemical treatises were attributed to him, from the late 15th century to the 17th century, the most famous being “The Book of Hieroglyphic Figures” published in 1612. Thus, “the most popular of French alchemists never practiced alchemy.”

Biography

For a character of the time not belonging to the nobility, there is relatively extensive documentation on Nicolas Flamel: the records of the parish of Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie, compiled in the 18th century, various personal documents of him and his wife including his will, as well as descriptions and illustrations, posthumous to his death, of the buildings and religious monuments he had built.

Flamel, Public Writer, and Sworn Book Merchant

Nicolas Flamel was born around 1340 (rather than around 1330 as often indicated), perhaps in “Pontoise, seven leagues from Paris.” He escaped the Black Death of 1348 in his youth, which claimed between a third and half of the European population. His life unfolded in Paris during the Hundred Years’ War, from the Battle of Crécy in 1346 to that of Agincourt in 1415. In 1389, he had to attend, with all the Parisian bourgeois dressed in red and green, the entry into Paris of Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, and he lived just before his death in 1418, the Parisian disturbances of the civil war between Armagnacs and Burgundians and the revolt of the Cabochiens (1413). From the 13th century, the foundation of universities but also the development of secular literature and reading in the nobility and the upper bourgeoisie led to the establishment of lay workshops for copying and illuminating, which until then had been the prerogative of monasteries. They were established in major cities, especially in Paris.

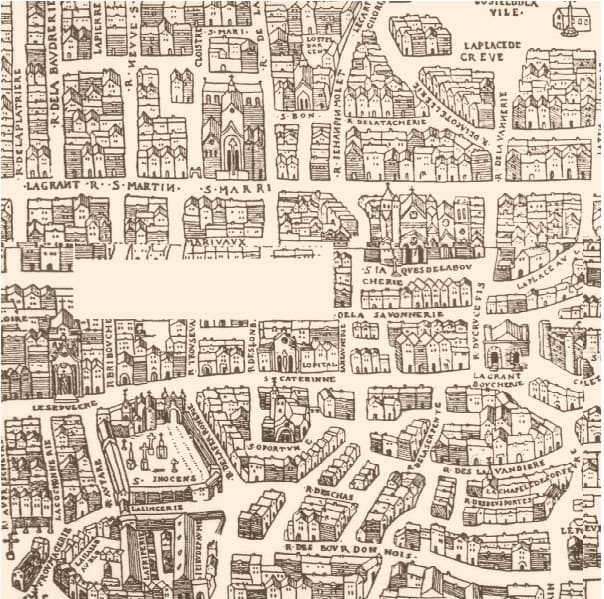

He began a career as a copyist and public writer in Paris, in a small shop next to the church of Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie, on the Rue des Écrivains. He may have been the elder brother or a relative of Jean Flamel, secretary and librarian to the great bibliophile Jean I de Berry (the one from the “Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry”). He later bought a house opposite the shop, at the corner of Rue des Écrivains and Rue de Marivaux (renamed Rue Nicolas-Flamel in 1851), where he lived and set up his workshop, under the sign of La Fleur de Lys. This house, decorated with engravings and religious inscriptions, and with the motto “Let everyone be content with what they have, He who lacks sufficiency has nothing,” attests to the wealth Flamel acquired, although, compared to other much more luxurious bourgeois residences of the time, it does not seem to have been exceptional. Rue de Rivoli, much wider, now covers Rue des Écrivains, the location of Flamel’s house, and most of the church, of which only the Saint-Jacques Tower remains (built at the beginning of the 16th century, a century after Flamel’s death).

Probably after 1368, he became a sworn book merchant (sworn because he had to swear an oath to the University of Paris), a member of the privileged category of “booksellers, parchment makers, illuminators, writers, and bookbinders, all people belonging to various sciences and known in the Middle Ages under the generic term of clerics. They depended on the University and not on the jurisdiction of the provost of Paris, like other merchants.” They were notably exempt in principle from taxes (direct taxes). Flamel also tried in 1415 to invoke this privilege to avoid paying a tax.

Nicolas and Pernelle

Around 1370, he married a woman twice widowed, Pernelle, and in 1372, they made a mutual bequest of their property before a notary, a donation that was renewed several times and excluded from Pernelle’s inheritance her sister and her children. Childless themselves, the Flamel couple began to finance pious works and constructions.

In order to empty the pits of the Cemetery of the Innocents, the bourgeois of Paris had charnel houses built all around it, in the 14th and 15th centuries, where the exhumed bones were piled up and left to dry, high up, above arcades. In 1389, Nicolas Flamel had one of these arcades built and decorated, on the Rue de la Lingerie side, where there were also public writer’s shops. Carved on it, around a black figure representing death, were Nicolas Flamel’s initials in Gothic letters, a poem, and religious inscriptions, “writings to stir people to devotion” according to Guillebert de Mets in his Description de Paris (1434). The same year, he financed the renovation of the portal of Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie, where he was depicted in prayer with his wife, at the foot of the Virgin Mary, Saint James, and Saint John.

Pernelle died in 1397. Just before her death, her family tried to annul the mutual bequest between the spouses. This led to a lawsuit between the heirs of Pernelle’s sister and Nicolas Flamel, which he eventually won. After his wife’s death, he continued to finance pious constructions and engaged in real estate investments in Paris and the surrounding areas.

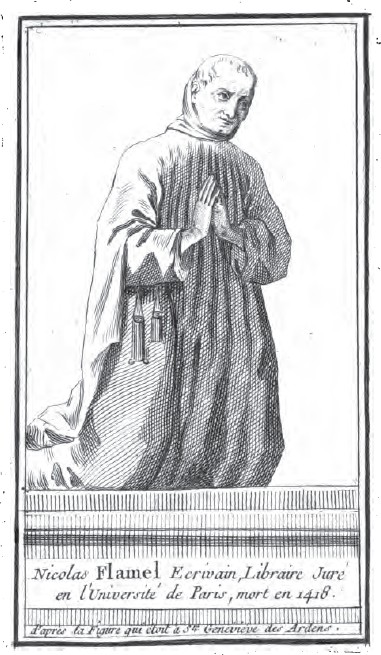

In 1402, he rebuilt the portal of the church of Sainte-Geneviève-la-Petite, which was located on the Île de la Cité, along Rue Neuve-Notre-Dame, on the site of the current “parvis Notre-Dame – place Jean-Paul-II”. It was called Sainte-Geneviève-des-Ardents from the beginning of the 16th century and destroyed in 1747. His statue, dressed in a long hooded robe, and with a writing tablet, symbol of his profession, was placed in a niche next to the portal. In 1411, he financed a new chapel of the hospital of Saint-Gervais (which was opposite the church of Saint-Gervais), and seems to have contributed to the renovations of the churches of Saint-Côme and Saint-Martin-des-Champs. In 1407, he had a tomb built for Pernelle in the Cemetery of the Innocents, on which he had an epitaph engraved in verse.

That same year, he had several houses built to accommodate the poor, on which were seen “many figures engraved in the stones with an N and a Gothic F on each side.” The best-known, and the only one still existing today, is the house of Nicolas Flamel, also called “with the large gable,” on Rue de Montmorency (now at No. 51). In addition to Flamel’s initials and various figures including musical angels, it bears the inscription: “We men and women laborers residing in the porch of this house which was built in the year of grace one thousand four hundred and seven are each bound to say every day a Pater Noster and an Ave Maria praying to God that his grace may grant pardon to the poor sinners deceased Amen.” Today baptized “Nicolas Flamel’s house,” although nothing indicates that he ever lived there, it is reputed to be one of the oldest dwellings in Paris.

Flamel also owned a number of houses in Paris and the surrounding villages, some of which brought in rents, but others were abandoned and in ruins. With the success of his activity as a copyist and bookseller, and the contribution of his wife Pernelle, twice widowed before marrying him, these real estate investments, made in the context of the economic depression of the Hundred Years’ War, probably contributed to his fortune.

Gravestone and Will

He died on [date], and was buried in the church of Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie where his gravestone was installed on a pillar below an image of the Virgin. The church was destroyed at the end of the revolutionary period, around 1797. The gravestone, however, was preserved and bought by an antique dealer from a fruit and vegetable seller on Rue Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie, who used it as a stall for her spinach. Bought back in 1839 by the Paris City Hall, it is currently located in the Cluny Museum: “The late Nicolas Flamel, formerly a writer, left by his will to the work of this church certain rents and houses, which he had acquired and bought during his lifetime, to perform certain divine services and distribute money each year through alms touching the Quinze Vingt, the Hôtel Dieu, and other churches and hospitals in Paris. Pray here for the deceased.” His remains, as well as those of his wife Pernelle buried with him, are then transferred to the catacombs of Paris.

The number and ostentatious nature of his pious foundations, in fact relatively modest, and the accumulation in his will (now kept at the National Library) of bequests of small amounts probably contributed to amplifying the importance of his fortune in the memory of the time. Shortly after his death, Guillebert de Mets in his Description de la ville de Paris (1434) speaks of Flamel as the “scribe who made so many alms and hospitalities and built several houses where craftsmen lived below and from the rent they paid, poor laborers were supported above.” And as early as 1463, during a lawsuit concerning his succession, a witness already said that “[Flamel] was reputed to be half richer than he was.” It was in this context that the rumor arose that he owed his wealth to the discovery of the alchemists’ philosopher’s stone, capable of transforming metals into gold.

The Legend of the Alchemist

How One Becomes an Alchemist

The myth of Nicolas Flamel the alchemist is the result of several phenomena of alchemical tradition. First of all, from the 15th century, the belief in the alchemical origin of certain bourgeois fortunes of the Middle Ages: besides Flamel (the most famous), this was the case of Jacques Cœur (c. 1400-1456), Nicolas le Valois (c. 1495-c.1542) (the richest man in Caen and founder of the Hôtel d’Escoville), or the German merchant Sigmund Wann (c. 1395-1469). Then there was the pseudepigraphy, by which alchemical treatises were attributed to ancient (Aristotle, Hermes Trismegistus, etc.) or medieval (Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas, Raymond Lulle, Arnaud de Villeneuve…) authorities, to compensate for “the marginality of a discipline that was never really integrated into university knowledge.” Finally, with the Renaissance, “the use of allegorical language and pictorial symbolism became systematic” in alchemical texts; this led, from the mid-16th century onwards, to an “alchemical exegesis” that sought a hidden meaning in both biblical texts and the stories of Greco-Roman mythology (especially the legend of the Golden Fleece), and finally in the symbolic decorations of medieval architecture.

The oldest trace of this legend is a text from the late 15th century, Le Livre Flamel, which is actually the French translation of a 14th-century Latin treatise, the Flos florum (The Flower of Flowers), then attributed to Arnaud de Villeneuve. This text gained some circulation, and a shortened version of it was translated into English in the mid-16th century. Other treatises were attributed to Flamel during the 16th century. This is notably the case of the Livre des laveures, which is actually the French translation of the Rosarius, a Latin treatise from the 14th century by the English alchemist John Dastin: on a 15th-century manuscript, the name of the owner was scratched out and replaced by that of Flamel.

At the same time, the idea arose that an alchemical meaning was hidden in the religious allegorical figures adorning the arcades of the cemetery of the innocents. The first trace is found in the book De antiquitate et veritate artis chemicæ (On the antiquity and truth of the chemical art) (1561) by the alchemist Robert Duval (a treatise that will be placed at the beginning of the first volume of the great alchemical anthology Theatrum Chemicum in 1602): “To this category of fictions belongs the enigma of Nicolas Flamel, who shows two serpents or dragons, one winged, the other not, and a winged lion, etc.” This idea is also found in prose commentaries from the second half of the 16th century on the poem Le Grand Olympe (which makes an alchemical interpretation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses). Still in 1561, Robert Duval, in his collection of alchemical poems De la Transformation métallique: Trois anciens traités en rithme françois, attributed to Flamel the Sommaire philosophique, probably because it also presented the motif of the two dragons (the dragon being one of the main alchemical symbols). The poem, which addresses “Who wants to have knowledge / Of metals & true science / How to transform / And from one to the other change,” takes up the classical alchemical theory that all metals are composed of two “seeds”: sulfur, fixed and masculine, and mercury (quicksilver), volatile and feminine.

The legend was taken up several times from 1567 to 1575 by the influential Paracelsian physician Jacques Gohory. At that time, one of the most hackneyed topoi of alchemical literature since the Emerald Tablet appeared, and it suited the bookseller Flamel well: the discovery of an ancient book containing the secret of the philosopher’s stone. It was first introduced by Noël du Fail in 1578, who, in support of Paracelsus’ miraculous healings, cited the most famous alchemists including “Nicolas Flamel, Parisian, who from a poor writer he was, & having found in an old book a metallic recipe that he tried, became one of the richest men of his time, as evidenced by the splendid buildings he built in the cemetery S. Innocents, at Saincte Genevieve des ardens, at S. Jaques la Boucherie, where he is in half relief, with his writing desk on the side, & the hood on the shoulder estimated rich he and his Perronelle (it was his wife) of fifteen hundred thousand ecus, in addition to the immense alms & endowments he made.” The idea gained ground, as it is found in 1592 in a note at the end of a manuscript of an alchemical text La Lettre d’Almasatus.

The legend became so popular that it was mocked in 1585 by Noël du Fail (who had apparently changed his position) in his Tales and Discourses of Eutrapel (1585), while Flamel appeared as an alchemist and author of the Philosophical Summary in the notices of the French Libraries by La Croix du Maine (1584) and Antoine du Verdier (1585). La Croix du Maine also reports rumors that were circulating at the time, according to which Flamel’s wealth did not come from his alchemical talents, but from the fact that he would have appropriated the claims of the Jews, then expelled from Paris (Charles VI had signed an expulsion edict in 1394). It was to conceal this fact that he would have made people believe that he had discovered the philosopher’s stone and would have financed pious foundations.

It crossed borders in 1583, when the Belgian Paracelsian Gérard Dorn translated into Latin passages from the Philosophical Summary, and it is found in Germany in 1605 and in England in 1610. All the ingredients were there for the appearance in 1612 of the most famous work attributed to Flamel: The Book of Hieroglyphic Figures.

The Book of Hieroglyphic Figures

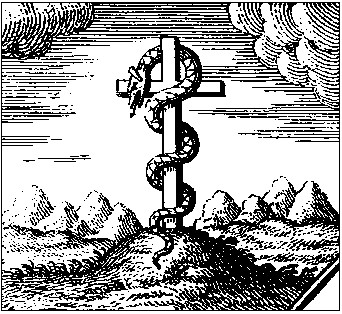

In 1612, in Paris, Three Treatises of Natural Philosophy Not Yet Printed are published, by Pierre Arnauld, lord of La Chevallerie, a native of Poitou. In addition to two treatises in Latin and French versions by Artephius and Synesius, there is a text in French: “The hieroglyphic figures of Nicolas Flamel, as he placed them in the fourth arch he built at the Cemetery of the Innocents in Paris, entering through the main gate of Rue S. Denys, and taking the right hand; with their explanation by Flamel himself.”

The work presents itself as the translation from Latin of a text by Flamel written between 1399 and 1413. Following the trope of alchemical literature about the discovery of an ancient book, Flamel recounts that he acquired for two florins a mysterious and ancient book in Latin, made of “three times seven sheets” of bark bound in a copper cover “all engraved with letters and figures.” On the first sheet, one finds the title “The book of Abraham the Jew, prince, Levite priest, astrologer and philosopher, to the people of the Jews by the wrath of God, scattered in Gaul, greetings. D. I.”. This book, written by a “very learned man,” explains that, “to help his captive nation pay tributes to the Roman emperors, and to do other things, which I will not say, he taught them the metallic transmutation in common words […] except for the first agent of which he said nothing, but […] he painted it, and depicted it with very great artifice.” The text of the book of Abraham the Jew thus explains the process of the Great Work (which Flamel does not repeat) without specifying the initial ingredient, the prima materia (the alchemists’ raw material), which is only given through mysterious illuminations, which are described but not reproduced in the Book of Hieroglyphic Figures.

Despite the help of his wife Pernelle, Nicolas Flamel fails at the Great Work for twenty-one years (the same number of years as the book’s sheets) for not understanding the illuminations. He then goes on a pilgrimage to Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle, where he meets an old converted Jewish doctor, who finally explains the illustrations to him.

Back in Paris, he finally succeeds in transmuting mercury into silver, then into gold, on [date]: “I projected it with red stone onto a similar quantity of mercury […] which I truly transmuted into almost as much pure gold, certainly better than common gold, softer and more pliable.”

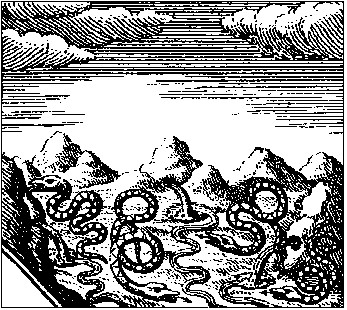

With the fortune thus acquired, Flamel and his wife “founded and endowed fourteen hospitals in this city of Paris, built completely anew three chapels, decorated seven churches with great gifts and good incomes, with several repairs in their cemeteries, besides what we had done in Boulogne, which is hardly less than what we have done here” (much more than the donations and works of the historical Flamel). And Flamel had “hieroglyphic figures” painted on an arcade of the cemetery of the innocents, which have both a theological interpretation and a “philosophical interpretation according to the magisterium of Hermes.” He first briefly gives the theological explanation; thus “the two dragons united […] are the sins which are naturally intertwined [chained to each other]; for one at its birth from the other: some of them can be easily chased away, as they come easily, for they fly at all times towards us. And those who have no wings cannot be chased away, such as the sin against the Holy Spirit.” He then gives, in a significantly more extensive manner, the explanation of the alchemical sense, an explanation in which the symbolism of colors takes a prominent place: “these are the two principles of philosophy that the wise men dared not show to their own children. The one which is below without wings, it is the fixed, or the male; the one which is above, it is the volatile, or the black and obscure female […] The first is called sulfur, or warmth and dryness, and the latter quicksilver, or coldness and humidity. These are the sun and the moon of mercurial source…”

Dating and Attribution

No medieval original of either the Book of Hieroglyphic Figures or the Book of Abraham the Jew has been found. Two Latin manuscripts of the Book of Figures have recently come to light, but they turn out to be “Latin translations” of the French text from 1612 made in the early 17th century.

In fact, everything indicates that this is a text written between the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century: the vocabulary (starting with the word Hieroglyph), the anachronisms (the text mentions the name of the alchemist Lambsprinck, mentioned for the first time by Nicolas Barnaud in 1599). The true source is a famous collection of medieval alchemical treatises, the Artis auriferae, published in 1572 (In The Hieroglyphic Figures, alchemical theories are often presented in the same order, but sometimes in reverse).

According to Claude Gagnon, P. Arnaud de la Chevallerie would be the pseudonym of Béroalde de Verville (1556-1626) (in the form of the imperfect anagram “Arnauld de Cabalerie”), a writer interested in alchemy and cabala, and best known today for his satire Le Moyen de Parvenir (1617). In support of this thesis, Gagnon found in a note by a 17th-century bibliographer on a copy of La Croix du Maine’s Bibliothèque françoise, the title of a work by Béroalde: Les aventures d’Ali el Moselan surnommé dans ses conquêtes Slomnal Calife, Paris 1582, translated from Arabic by Rabi el Ulloe de Deon. “Slomnal Calife” being the anagram of “Nicolas Flamel,” and “Rabi el Ulloe de Deon” that of “Béroalde de Verville.” Another element is that Béroalde de Verville published, in the same year and with the same publisher as The Hieroglyphic Figures, the Palais des curieux in which he warns his alchemist readers against “those who deceive you, and who under the beautiful tales of Flammel & others spy on your souls, to ruin them.”

However, this attribution did not convince some specialists of Béroalde de Verville. On the other hand, Bruno Roy takes up Gagnon’s hypothesis about the author of the Hieroglyphic Figures: “In the end, Béroalde’s Flamel is much more attractive to us than the real bourgeois bigot, megalomaniac, and litigious who lived in the 14th century.” Another possibility is the discovery by François Secret in early 17th-century alchemical manuscripts of the name of a “Sieur de la Chevalerie de Chartres” (therefore from Beauce rather than Poitou), but about whom nothing more is known.

Fortune of the Myth

This text was immediately successful and widely popularized the myth of Flamel, who became the quintessential French alchemist. In addition to the fact that his supposed fabulous fortune, traces of which are still visible in Paris, testified to his success in the search for the philosopher’s stone, this success may be partly due to the fact that during the Counter-Reformation, Flamel offered an alchemist figure revering the Virgin and the Saints, while the discipline was dominated by the reformed alchemists of the “Paracelsian revival,” within which other alchemical literary mystifications were born, promising success as well: Solomon Trismosin (appeared in 1598), the alleged master of Paracelsus (1493/4-1541), Basil Valentine (1600), who would have been a Benedictine monk of the 15th century, as well as the Rosicrucian manifestos (1614-1615) and The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz (1616).

The Book of Hieroglyphic Figures had many reprints and translations. As already indicated, pseudo-Latin originals were forged. The figures from the Book of Abraham the Jew, which are merely described in the 1612 edition, were quickly represented in manuscripts and in subsequent editions. This tradition continued until the 18th century, when in German in Erfurt in an Uraltes chymisches Werck (1735): “A very ancient alchemical work by Rabbi Abraham Eleazar, which the author wrote partly in Latin and Arabic, partly in Chaldean and Syriac, and which was then translated into our German language by an anonymous author,” and which contains a new version of the figures from the Book of Abraham.

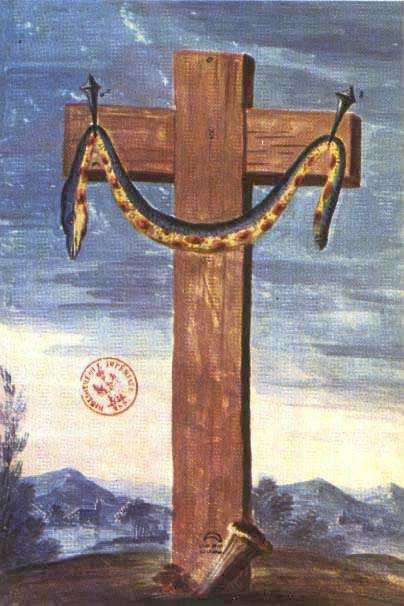

“A cross where a serpent was crucified.”

“Deserts, amidst which flowed several beautiful fountains, from which emerged several serpents, running here and there.”

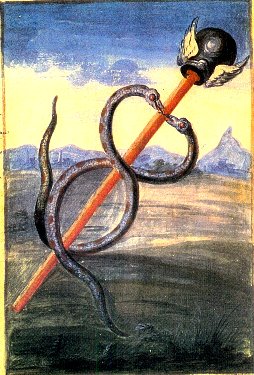

“A young man with wings on his heels, holding a caduceus in his hand, entwined with two serpents, with which he struck a helmet covering his head, […], against him came running and flying with open wings, an old man, who on his head had a clock attached, and in his hands a scythe like death, from which, terrible and furious, he wanted to cut off Mercury’s feet.”

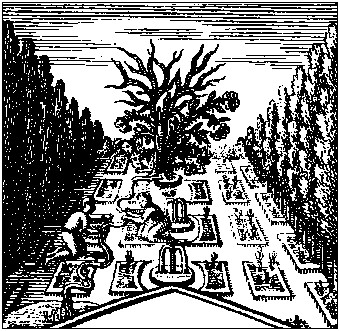

“A beautiful flower at the top of a very high mountain, which the north wind shook very roughly, it had a blue stem, white and red flowers, leaves shining like fine gold, around which northern dragons and griffins made their nest and dwelling.”

“A beautiful rose bush blooming in the middle of a beautiful garden, climbing against a hollow oak, at the feet of which bubbled a fountain of very white water, which was going to precipitate into the abysses, nevertheless passing, first, between the hands of endless peoples who dug in the earth, seeking it: but because they were blind, no one knew it, except someone, considering the weight.”

“A king with a large knife, who had soldiers kill in his presence a great multitude of small children, whose mothers wept at the feet of the pitiless soldiers, the blood of whom little children was then collected by other soldiers, and put into a large vessel, in which the sun and the moon came to bathe.”

Other texts were attributed to Flamel. In 1619 appeared, along with the Treatise on Sulphur by the Pole Michael Sendivogius, a Treasury of Philosophy or Original of the Desired Desire of Nicolas Flamel, which is nothing other than a French version of the Thesaurus philosophiae by Efferarius Monachius (14th century). The attribution is probably related to the Book of Washings which begins with “The desired desire, and the price that no one can appraise.” The same goes for The Great Enlightenment of the Philosopher’s Stone for the transmutation of all metals (1628), a French translation of the Italian treatise Apertorio alfabetale (1466 or 1476) by Cristoforo Parigino (Christophe de Paris).

In 1655, Pierre Borel, Louis XIV’s personal physician and the first bibliographer of alchemy, reported in his Treasure of Gaulish and French research and antiquities a number of rumors and rumors that were circulating at the time about Flamel: King Charles VI would have sent, to inquire about his wealth, his master of requests Mr. de Cramoisy, whose silence Flamel would have bought with a matras (vessel) full of projection powder (one of the forms of the philosopher’s stone); Flamel’s house would have been searched for the Book of Abraham the Jew, which would have been eventually found by Cardinal Richelieu shortly before his death in 1642. It was also said that Richelieu had executed an alchemist named Dubois who claimed to be the heir to Flamel’s secret.

At the same time, the historian of Paris Henri Sauval (1623-1676) was more doubtful: “The hermetics who seek everywhere the Philosopher’s Stone without being able to find it, have meditated so much on some portals of our Churches, that in the end they found what they pretend. […] They distill the spirit to quintessentialize Gothic worms & figures, some of them in the round, others scratched, as they say, on the stones of the house on the corner of Rue Marivaux, as well as of the two Hospitals which he [Flamel] had made on Rue de Montmorenci.”

Flamel in the Age of Enlightenment

Alchemy did not disappear with the 18th century and the Enlightenment. But while it retained a certain scientific credibility (Newton, during his alchemical studies, was interested in the “hieroglyphs” of the Book of Figures and the Book of Abraham the Jew), because it did not seem possible to demonstrate the theoretical impossibility of transmutation, the failure of its practical realization gradually accentuated its moral and social discredit throughout the century. It was increasingly perceived as a ruinous chimera, as with Fontenelle (History of the Academy of Sciences 1722) and with Montesquieu in one of his Persian Letters (1721): Rica recounts that he met a man ruining himself because he believes he has achieved the great work, and who affirms to him: “This secret, which Nicolas Flamel found, but which Raymond Lulle and a million others always sought, has come to me, and I find myself today a happy adept.”

Along with the transmutation of metals, the prolongation of life was the other goal of alchemy, in the form of the elixir of long life (sometimes also called drinkable gold). At the time of the Count of Saint-Germain, who pretended to be immortal, the belief arose that Nicolas Flamel and his wife Pernelle were still alive. In 1712, Paul Lucas, the king’s antiquarian and great traveler, reported without too much belief in his Voyage of Mr. Paul Lucas, made by order of the king in Greece, Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Africa: Containing the description of Natolia, Caramania, & Macedonia, that a dervish he met in Turkey told him that the philosopher’s stone prolongs life by a thousand years, with as proof that he would have met Nicolas Flamel in the Indies three years earlier. His wife Pernelle would not have died either in 1397 but would have settled in Switzerland, joined in 1418 by her husband. The legend continued and it was said that Flamel had met Count Desalleurs, ambassador of France in Turkey from 1747 until his death in 1754, and in 1761, with his wife and their son, he had been seen at the opera.

In 1758, Father Étienne-François Villain published a detailed study on the history of his parish of Saint-Jacques la Boucherie, in which he rejected the legend of Flamel the alchemist, first asserting that Flamel’s wealth was far from being as considerable as what was said, for example by Nicolas Lenglet Du Fresnoy in his History of Hermetic Philosophy (1742) who claimed that Flamel’s pious foundations were “more considerable than those made by Kings & Princes themselves”. Secondly, Villain emphasized that the Book of Hieroglyphic Figures was an apocryphal work due to its alleged translator, Pierre Arnauld de la Chevallerie. He was vigorously attacked by Antoine-Joseph Pernety, known as Dom Pernety, a former Benedictine with a passion for hermeticism, relayed by Fréron in his journal The Literary Year, while Villain, supported by the Jesuits of the Journal de Trévoux, published in 1761 a more complete study:

Critical History of Nicolas Flamel and Pernelle his wife; collected from ancient deeds which justify the origin and mediocrity of their fortune against the imputations of alchemists. Pernéty criticized Villain’s historical method in particular: “Can one reasonably imagine that a Hermetic Philosopher should advertise himself as such? And Mr. Abbé V… did he think to find Flamel the Philosopher in the rent contracts, the receipts, etc. of Flamel the private man? […] Was it necessary to employ more than 400 pages to overwhelm us with the minute details of these rents, these receipts, etc. of Flamel conducting himself like a good Christian Bourgeois? Mr. Abbé V… to convince himself that Flamel deserves the name of Philosopher, would he want him to sign, in the contracts he made, in the receipts he received or given, Nicolas Flamel, Hermetic Philosopher?” Pernéty argues that there exists a Breviary of Flamel, dated 1414. This Breviary, found in two illustrated manuscripts from the 18th century, which uses vocabulary and syntax unknown in the 15th century and which quotes The Book of Hieroglyphic Figures, is also a later apocryphal work.

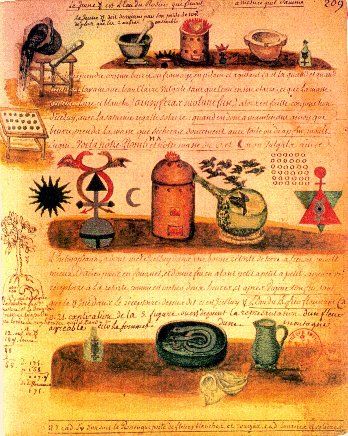

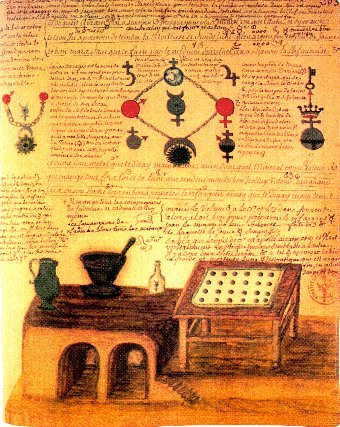

Excerpts from Flamel’s Alchemy, by Chevalier Denys Molinier – 18th-century manuscript.

The conclusions of Abbé Villain were vigorously attacked by the Ardennes alchemist Onésime Henri de Loos (1725-1785) in his work “Flamel avenged, his adaption defended, and tradition restored in its vigor against the attacks, insults of ignorance, against the fictions and impostures of criticism.” He concludes: “The commentary on the hieroglyphs is not and could not have been the work of a speculative philosopher, who only combines ideas, gropes for principles, and tries skillfully to draw conclusions from them. It is, on the contrary, the masterpiece of a man skilled in practice, a collection of the finest and most delicate observations of a master accustomed to seeing and seeing well; and who, by the force of a genius aided by habit, guesses everything, explains everything, and goes back to the secret causes of nature’s crises. No book is as filled with these traits that characterize an eyewitness: no book is less suitable for a beginner, it is only made for adepts. By this, undoubtedly, it is more precious and more estimable. No one will reproach Flamel for leading him into a labyrinth, since he declares at first that he closes the door to it, and that it will never be opened, unless one has found the key elsewhere. All this, well considered, and referring to the other reasons I have mentioned, excludes Mr. de la Chevallerie and Gohorry.”

Flamel in the Contemporary Era

With the advent of modern chemistry in the late 18th century, alchemy lost all its scientific credibility and experienced a considerable decline as a discipline. But “romanticism invents the image of a cursed, misunderstood, heroic and persecuted alchemical science.” Flamel becomes the quintessential figure, especially in France. In 1828, the young Gérard de Nerval made a play about him (Nicolas Flamel), as did Alexandre Dumas in 1856 (La Tour Saint Jacques). Frollo, the alchemist archdeacon of Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) by Victor Hugo, goes to contemplate the hieroglyphic figures in the cemetery of the Innocents. In 1842, he is the hero of Le Souffleur, a fantastic tale by Amans-Alexis Monteil in his Histoire de Français des divers états, aux cinq derniers siècles.

The founder of occultism, Éliphas Lévi, assures in his History of Magic: “Popular tradition asserts that Flamel did not die and that he buried a treasure under the Tour Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie. This treasure contained in a cedar chest covered with blades of the seven metals, would be nothing else, say the enlightened adepts, than the original copy of the famous book of Abraham the Jew, with its explanations written by Flamel’s hand, and samples of projection powder sufficient to turn the Ocean into gold if the Ocean were Mercury.”

The occultists and hermeticists, Albert Poisson, Fulcanelli, Eugène Canseliet, and Serge Hutin, rejected the conclusions of Abbé Villain and continued to affirm that Flamel had been an alchemist. He naturally finds his place in the long succession of the great masters of the Priory of Sion, between 1398 and 1418, in the Secret Files of Henri Lobineau of the hoaxer Pierre Plantard (and is thus found as such in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code).

In 1929, Nicolas Flamel simultaneously inspired André Breton in the Second Manifesto of Surrealism and Robert Desnos in an article “The Mystery of Abraham the Jew” for the magazine Documents. Breton establishes an “analogy of purpose” between alchemical and surrealist research and, taking up the idea of Flamel as an alchemist, compares what “Abraham the Jew” and “Hermes” have been for him to what Rimbaud and Lautréamont represent for the surrealists, both precursors and initiators. However, by “reducing the ‘philosophical stone’ to being the symbol of the triumph of imagination, Breton does not act at all as an adept [but] diverts alchemical tradition and empties it of its metaphysical significance for the benefit of its poetic value.”

On the side of academic historians, as early as 1941, the medievalist Lynn Thorndike completely rejected the myth of Flamel the alchemist, confirmed by the work of Claude Gagnon, Robert Halleux, and Didier Kahn.

The view of alchemy today remains largely dependent on the antagonistic and complementary viewpoints of 19th-century positivism and occultism, and Flamel is, along with his contemporary Paracelsus, the figure referred to by Zénon, the physician, astrologer, and alchemist of the 16th century in “The Abyss” (1968) by Marguerite Yourcenar, which was based on “three major modern [at the time] works on alchemy: Marcellin Berthelot, La Chimie au Moyen Âge, 1893; C.G. Jung, Psychologie und Alchemie, 1944; J. Evola, La Tradizione ermetica, 1948.”

The character of Flamel the alchemist still appears today in esoteric literature, but also in popular literature, comics, and even video games.

“Honor and Posterity”

- Rue Nicolas-Flamel and Rue Pernelle in the 4th arrondissement of Paris.

- The Nicolas Flamel College in Pontoise.

- The Nicolas-Flamel high school of the BOULLE school, which hosts the Jewellery and Jewel Arts workshop.

Nicolas Flamel in Fiction

Movies

- Nicolas Flamel is mentioned and appears in J. K. Rowling’s Wizarding World franchise: in Chris Columbus’ Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, historical moments in Nicolas Flamel’s life are evoked (cf. the eponymous novel), while the character appears on screen in the spin-off Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: The Crimes of Grindelwald (set in 1927) to fight Gellert Grindelwald alongside the heroes. He is portrayed by Brontis Jodorowsky.

- In John Erick Dowdle’s film Catacombs, released on August 20, 2014, the philosopher’s stone is hidden in Paris by Nicolas Flamel.

- In Alexandre Castagnetti’s film Le Grimoire d’Arkandias, Nicolas Flamel is evoked as a magician who was a precursor of modern chemistry.

Television

In the television series Les Compagnons d’Eleusis (1975), Nicolas Flamel and Dame Pernelle are often mentioned.

Theater and Opera

- Gérard de Nerval, Nicolas Flamel, 1828.

- Alexandre Dumas, La Tour Saint-Jacques, 1856.

- Georges Bizet, Nicolas Flamel, 1865 (unfinished and never performed opera).

Novels

- Martine Basso and Jean-Jacques Lujan, The Testament of Nicolas Flamel, C.R.S editions coll. LiberFaber, 2015 (ISBN ). This novel sets its story in 1916, during the battle of Verdun: a mysterious case is unearthed. In 1968, Antoine, a young student, receives this object. He is eager to shed light on this gift in order to discover who Nicolas Flamel is…

- Michael Scott, in a series of 6 books titled The Secrets of the Immortal Nicolas Flamel: The Alchemist, 2008; The Magician, early 2009; The Sorceress, late 2009; The Necromancer, 2010; The Traitor in 2012; The Enchantress in 2013, Pocket Jeunesse.

- Léo Larguier, The Gold Maker Nicolas Flamel, 1936, J’ai lu, The Mysterious Adventure n° A220.

- Évelyne Brisou-Pellen, The Sorcerers’ Claw, 1996, Rageot Editions: appearance of Nicolas Flamel and Pernelle.

- Marie Desplechin, Verte, 1996, L’École des loisirs: the team against which Soufi plays football, when he is rendered invisible, comes from Nicolas Flamel College.

- J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, 1997: mentioned character but never encountered, Flamel is the creator of the Philosopher’s Stone, at the heart of the plot, thanks to which his wife, Pernelle, and he are still alive; they ultimately agree to die after the stone is destroyed. This is a historical nod from the novelist.

- Éric Boisset, The Arkandias Trilogy (book 1): he is mentioned.

- Éric Giacometti, Jacques Ravenne, The Blood Brother, 2007: Masonic thriller in which Flamel is one of the characters.

- Corinne De Vailly, The Gold Pieces of Nicolas Flamel, coll. “Phoenix: Time Detective”.

- Janine Durrens, Pernelle and Nicolas Flamel: novel, Calviac-en-Périgord, Ed. du Pierregord, coll. “Pierrefeu”, 2008, 477 p. (ISBN , OCLC , BNF ).

- Matthieu Dhennin, Saltarello, Actes Sud, 2009.

- Henri Loevenbruck, The Cathedrals of the Void, 2009, Flammarion, Nicolas Flamel in the context of a testament letter from which extracts are distilled throughout the novel tells us his true story, reminds us that he was not an alchemist at all, and reveals that he nevertheless discovered a secret.

- Patrick Mc Spare, The Heirs of Dawn, vol. 1: The Seventh Sense, Paris, Scrineo, 2013 (ISBN)

- Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code, 2003: Mentioned as the navigator of the Priory of Sion, from 1398 to 1418

- Pierre Pevel in The Paris of Wonders: the enchantments of Ambremer

- Victor Hugo in Notre-Dame de Paris

- Karim Berrouka in The Thing That Resembles a Machine

Comics and Cartoons

- The Gold Maker, 1977, 20th album of the Adventures of Spirou and Fantasio: he is the inventor of a gold-making machine.

- The Genie Wars, 1983, in the series Leonard: he appears during disputes between Leonard and Albert.

- The Secret of Nicolas Flamel, 1989, short story created by Bom and Seron in the tribute album to Gil Jourdan and Maurice Tilleux Les Enquêtes de leurs amis.

- Willy Vassaux, The Philosophers by Fire / Nicolas Flamel, 1990: main character

- The Alchemist’s Testament (1st and 2nd part) of the television series Blake and Mortimer, 1997.

- Belphégor, “The Secret of Master Flamel”.

- Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood (season 1, episode 7): Edward Elric mentions the “Flamel codex” which speaks of the Philosopher’s Stone, 2005.

- The Blood Brother, 2016, 3 albums about alchemy and Nicolas Flamel

Video Games and Board Games

- Assassin’s Creed Unity, 2014, a series of three missions entitled The Secret of Flamel aims to find Nicolas Flamel’s laboratory in Paris and seize his Elixir of Life before members of a monastic cult.

- Artus and the Secret Grimoire, 2004.

- The School of Nicolas Flamel, 2021, by Lalex Andrea, published by Jyde Games.