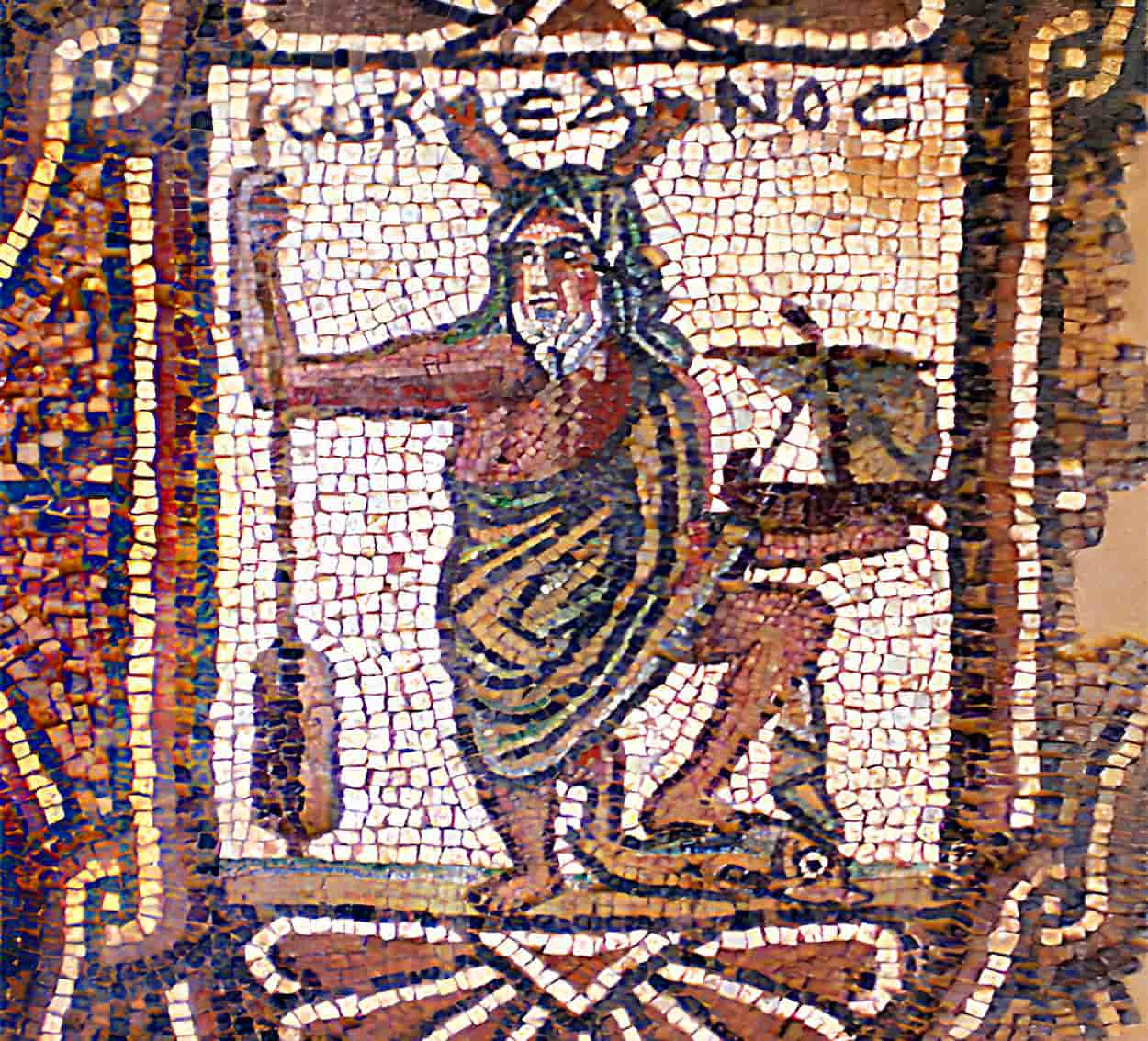

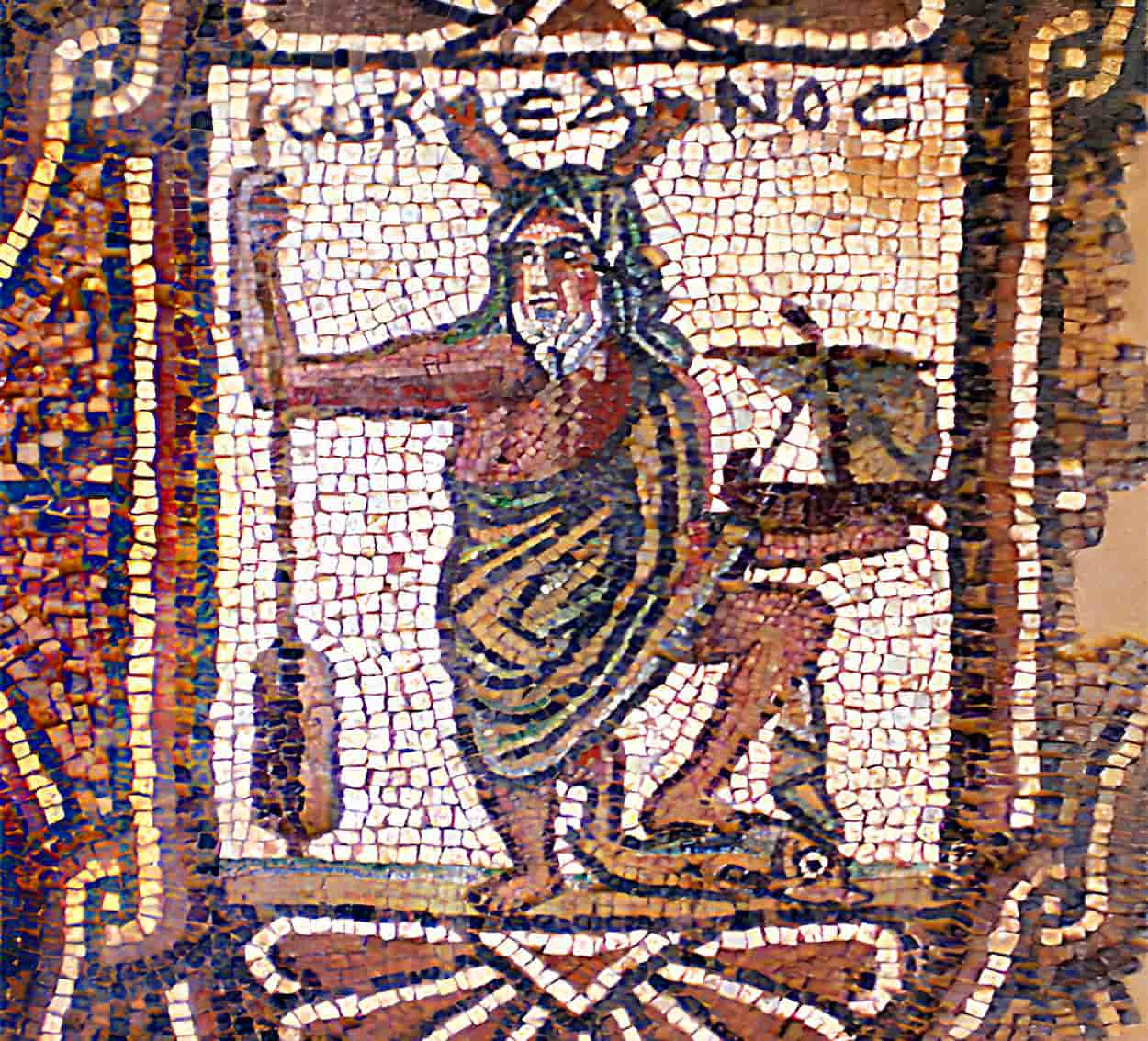

Oceanus: A Vast Stream That Surrounds the World

Oceanus is in Greek mythology the divine personification of a vast flowing stream that surrounds the inhabited world.

Oceanus is in Greek mythology the divine personification of a vast flowing stream that surrounds the inhabited world.