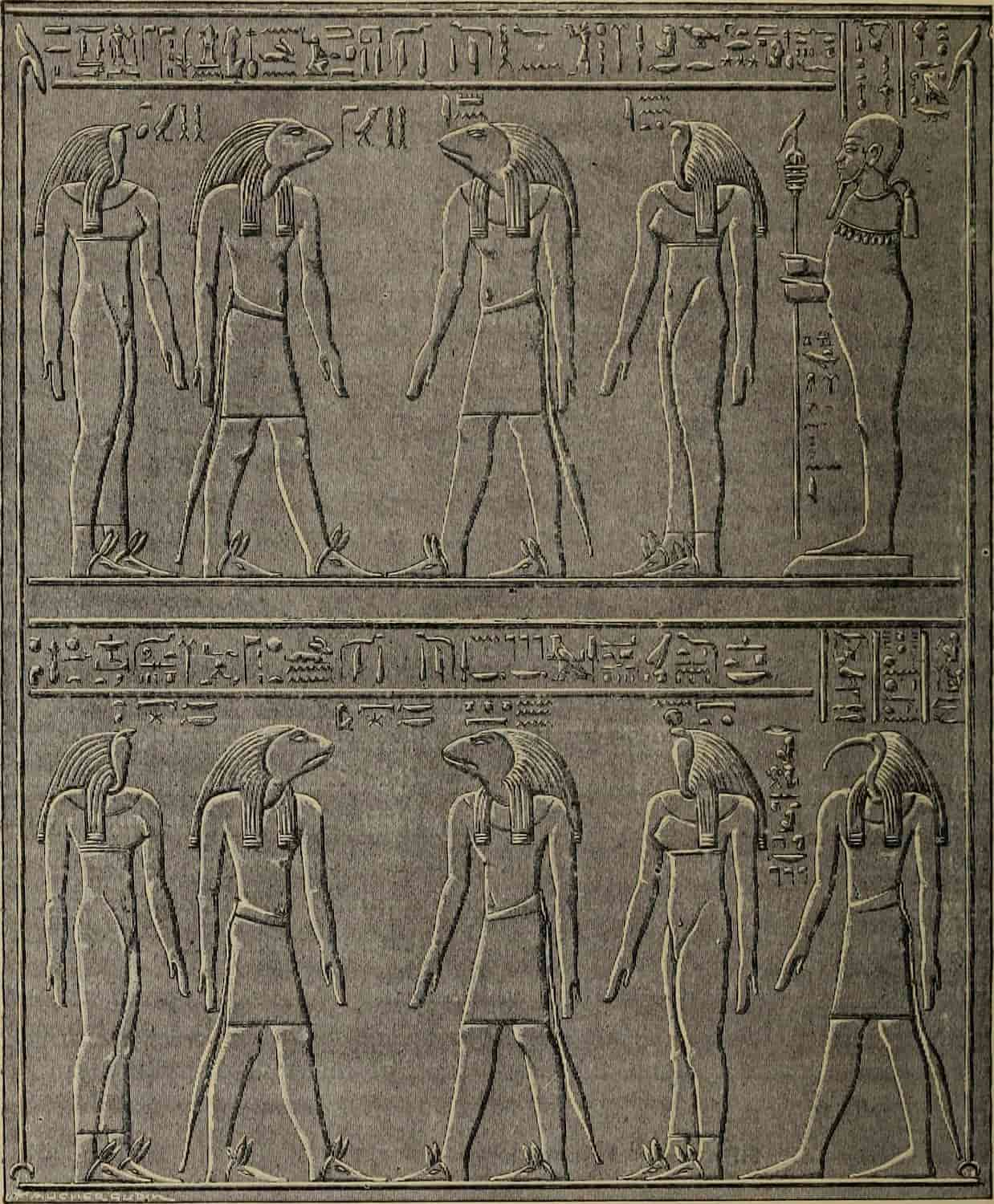

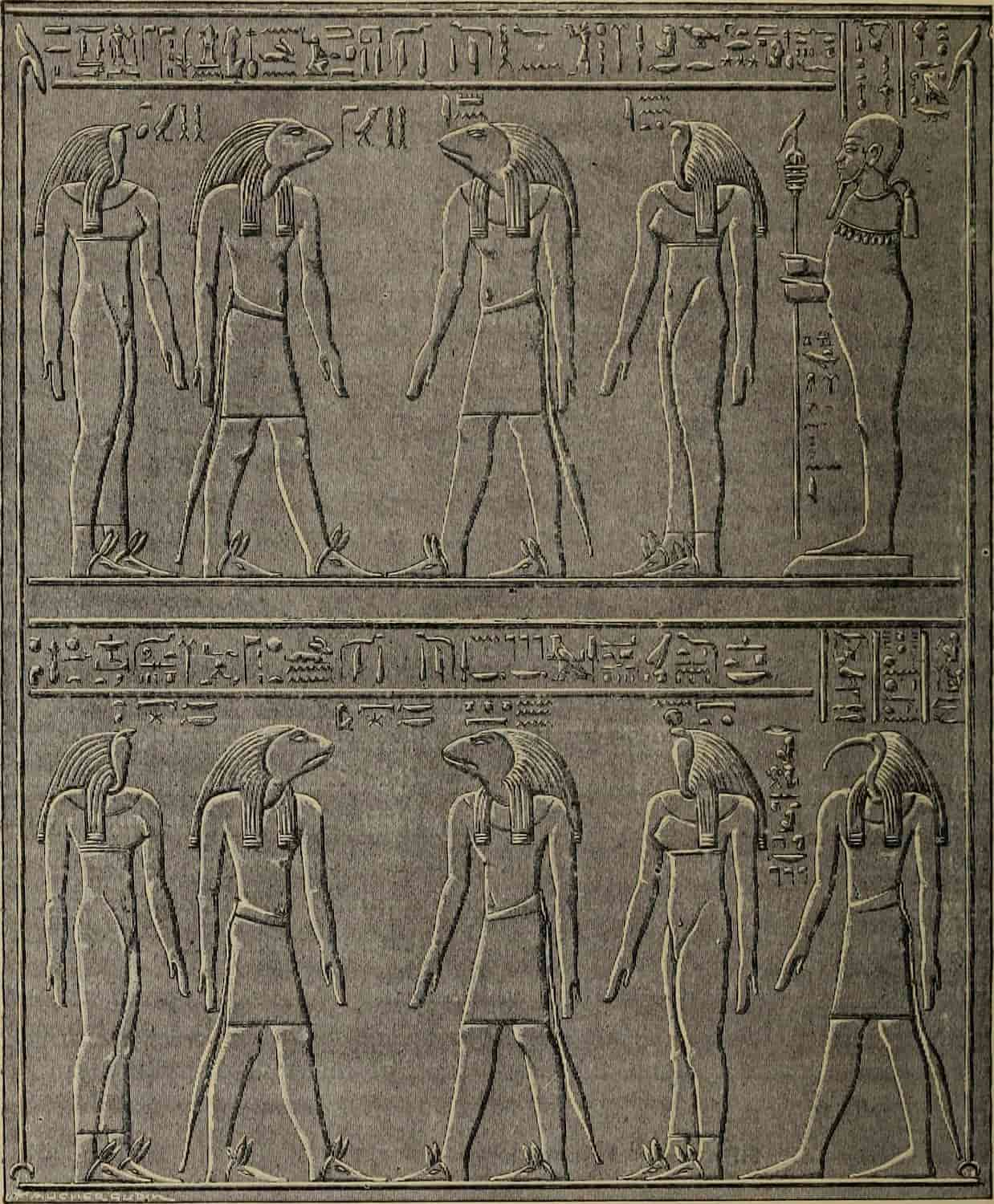

Ogdoad: Four Pairs of Parthenogenetic Egyptian Gods

The members of the Ogdoad were four pairs of parthenogenetic gods, each consisting of a male and a corresponding female element: Nun and Naunet, Heh and Hauhet, Kuk and Kauket, Tenemu and Tenemut.

The members of the Ogdoad were four pairs of parthenogenetic gods, each consisting of a male and a corresponding female element: Nun and Naunet, Heh and Hauhet, Kuk and Kauket, Tenemu and Tenemut.