There is a true treasure mine of the world’s earliest fish fossils in China, uncovered by paleontologists. The fossils, which are as ancient as 439 million years, prove that the first animals with jaws appeared earlier than previously believed. Scientists have published their findings in no less than four separate issues of “Nature,” and among them are the earliest known examples of cartilaginous fish and jawed armored fish fossils. This provides fresh data on the evolution of fish and the first vertebrates with jaws, which includes humans.

Almost all living vertebrates have their ancestry in ancient fish since they were the first vertebrates to develop a jaw. In the end, they gave rise to the Gnathostomata group, which literally means “jawed mouth,” to which we modern humans also now belong. However, the development of the first fishes, and therefore our earliest predecessors, has been the least explored area of evolutionary biology.

Dreadful gap in fossil records

The issue is that, according to DNA analyses, the first gnathostomes likely arose around 450 million years ago. However, fossils that would have been present in the same period are now absent. But fish fossils are so plentiful in the Devonian Period, which began about 419 million years ago, that it is sometimes known as the Age of Fishes. In the previous decade, paleontologists in China made the first discoveries of fish fossils that date back 425 million years.

According to the theory, the first jaw could be developed by the now-extinct armored fishes (Placodermi), which had a thick carapace of bone plates on the head and trunk but a still-undeveloped skullcap. This makes them, in theory, the ancestors of modern-day sharks and rays, which are cartilaginous fishes. But how about the bony fish that evolved into the terrestrial vertebrates that also eventually became our ancestors? The answers to these theories are now up for debate once again because of a scarcity of new fossil discoveries.

A prehistoric aquarium

A jawless species, the oldest armored fish to date, and three different early cartilaginous fish, making them the oldest known shark ancestors, were discovered in China’s Chongqing province by paleontologists led by You-an Zhu and Qiang Li of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

During the first discovery, scientists found the first Silurian fish fossil wholly intact. Over the last two years, researchers have been able to uncover hundreds more fossils with their ongoing digs. This location has the earliest known fossils of jawed vertebrates and fish from 436 million years ago, many of which are very well preserved and complete.

A fresh perspective on the evolution of vertebrates

Scientists can now test the long-debated theories regarding the evolutionary ancestry of humans. Important as they are for their age alone, the newly found fossils are much more so since they reveal for the first time the whole anatomy of the earliest fishes, from head to tail.

The first thing we can learn from the new discoveries is when vertebrates with jaws first appeared in the timeline. The fossils show that by the early Silurian Period (from 444 Mya to 420 Mya), there was already a great deal of morphological variation among mammals with jaws and wide distribution of the major phylogenetic groupings. This shows that these fishes’ ancestry goes back far further in time than was previously believed, according to researchers.

The first jaws were little and flimsy

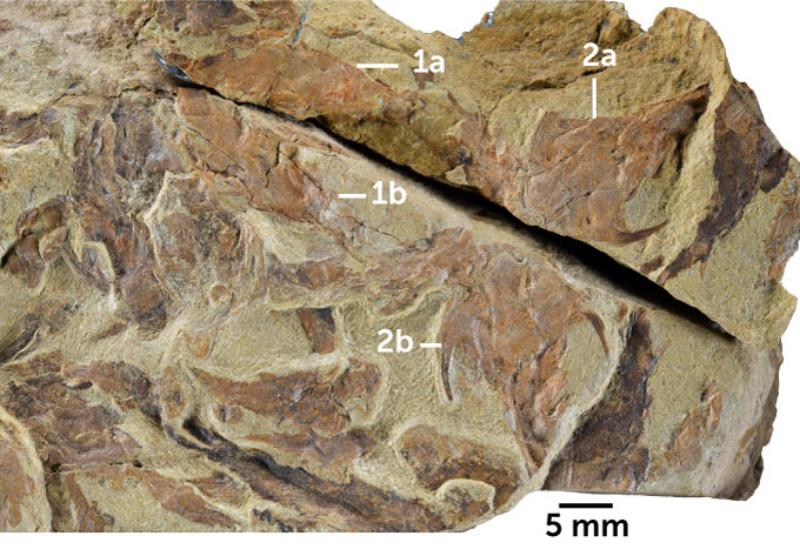

The tiny size of the fishes is one of the two most striking traits of this fossil collection, along with its tremendous variety. Since most species are just a few millimeters in length. This may be the reason why so few fossils of ancient fish have been found so far.

Vertebrates with jaws from Chongqing are tiny and fragile, indicating that they were likely poorly preserved outside of certain deposit types. On the other hand, it’s possible that fishes were only regionally spread at the time and the evolution of fishes with jaws was slower than that of their jawless forebears.

Fish with jaws but no frills

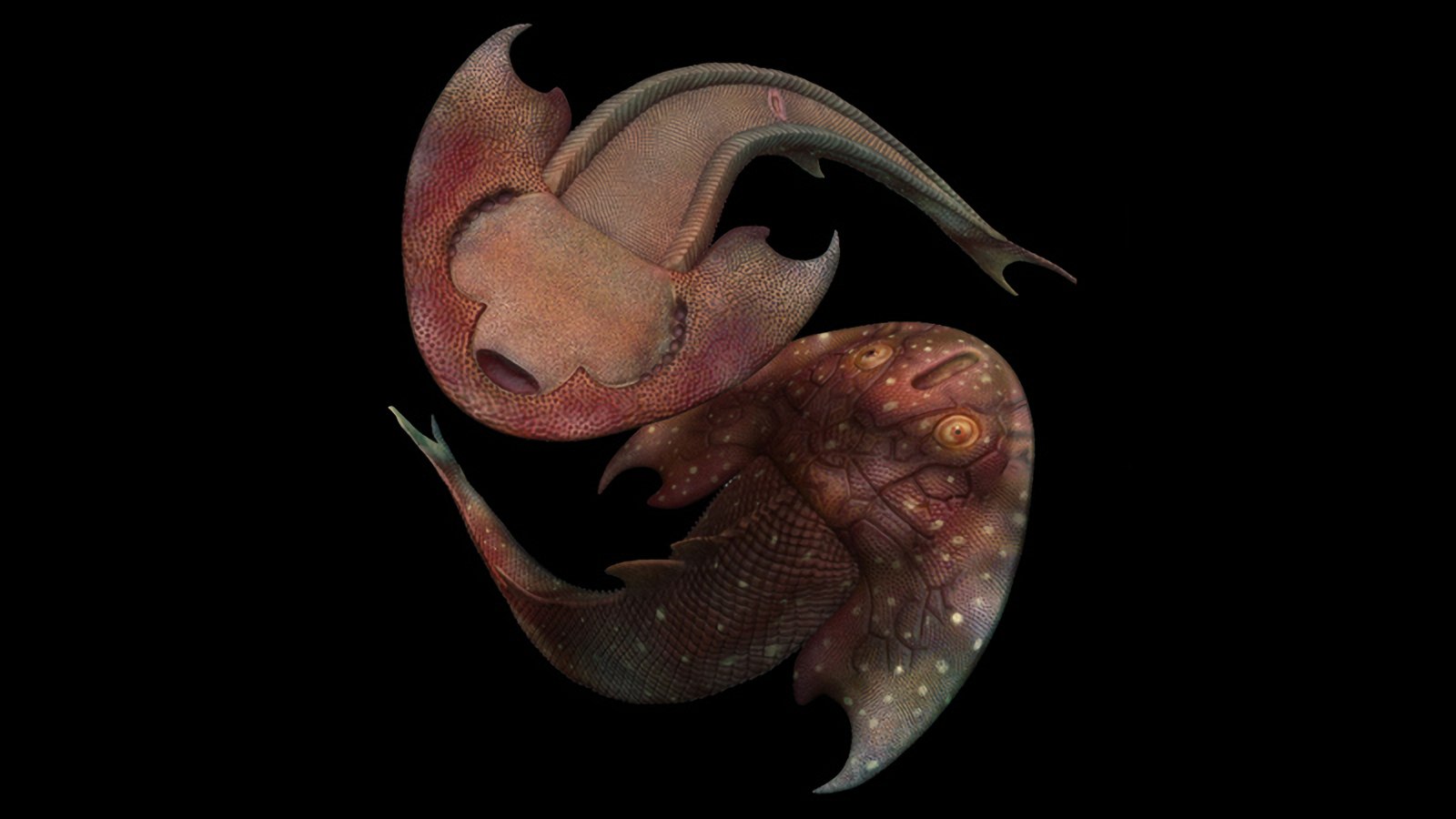

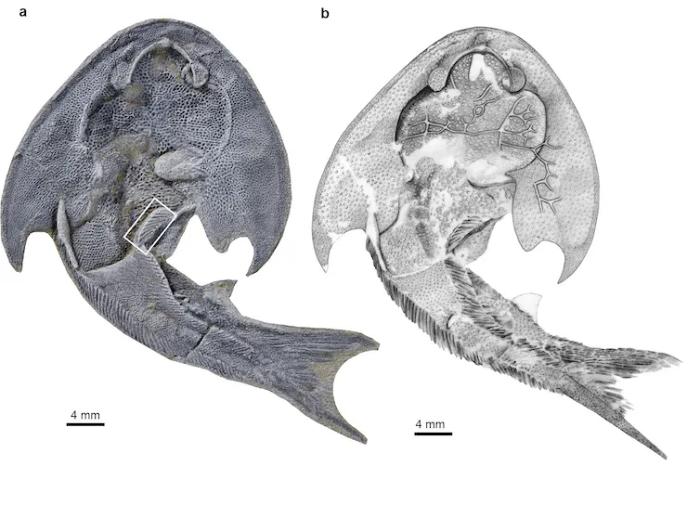

Yet another finding regarding the early fishes’ appearance is also revealed by the fossils. More than 20 individuals of the armored fish Xiushanosteus mirabilis have been found in Chongqing. These ancient fossils are mostly intact. The tiny Xiushanosteus combines the characteristics of many different types of armored fish.

Exciting, however, is the structure of the armored plates above its skull. The plates include a unique set of sutures that set them apart from the surrounding head plates. Researchers speculate that the change to the bony fishes’ skull plates could make its first appearance here.

Ancestor fishes with shoulder pads

Another unique trait may be seen in the remains of two primitive cartilaginous fish, the forerunners of modern sharks and rays. Shenacanthus vermiformis, a species discovered in Chongqing that is around 436 million years old, has many of the normal shark characteristics, but its shoulder region is covered by huge, hard armor plates, like those of an armored fish. Such armored fish and jawless have a full ring of thickened skin parts all the way around their bodies.

The Fanjingshania renovata, a shark fish that lived 439 million years ago and has a striking resemblance to the armored fish due to its armored shoulder region, is a pleasing example of a cartilaginous fish with a comparable structure. On the other hand, the fish has teeth and scales that are similar to those of bony fish. According to the research group led by Qujing Normal University’s first author Plamen Andreev, this combination distinguishes this ancient fish from all other known vertebrates.

New and exciting times

Together, these new fossils provide fascinating light on the timeframe during which the first animals with jaws initially appeared. There will undoubtedly be heated discussions on the unique properties of these new fossils and the complexities of their classification. After all, much remains unknown about the variety of the recently found fishes.

More jawed fishes from the Early Silurian have been found at these locations, although these have not yet been characterized. As a result, the study of primitive jawed fishes has entered a new and interesting epoch. (Nature, 2022; doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05136-8; doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05233-8)