The Oneiros (Greek Ὄνειροι Óneiroi, ‘Dreams’) are in Greek mythology the embodiment of dreams or dreaming. The singular term Oneiros (Ὄνειρος Óneiros) referring to a god of dreams is rare. More often, the Oneiros are mentioned as an unspecified group. In Hesiod’s Theogony, they are the children of Nyx (“Night”): “Nyx bore […] Hypnos along with the swarm of Oneiros.”

According to Homer, the land of dreams (demos oneiroi) is part of the underworld. It is located beyond the Okeanos, beyond the white rock and the gates of the sun, before reaching the Asphodel Meadow, where the shades of the dead reside.

True Dreams and Dream Gates

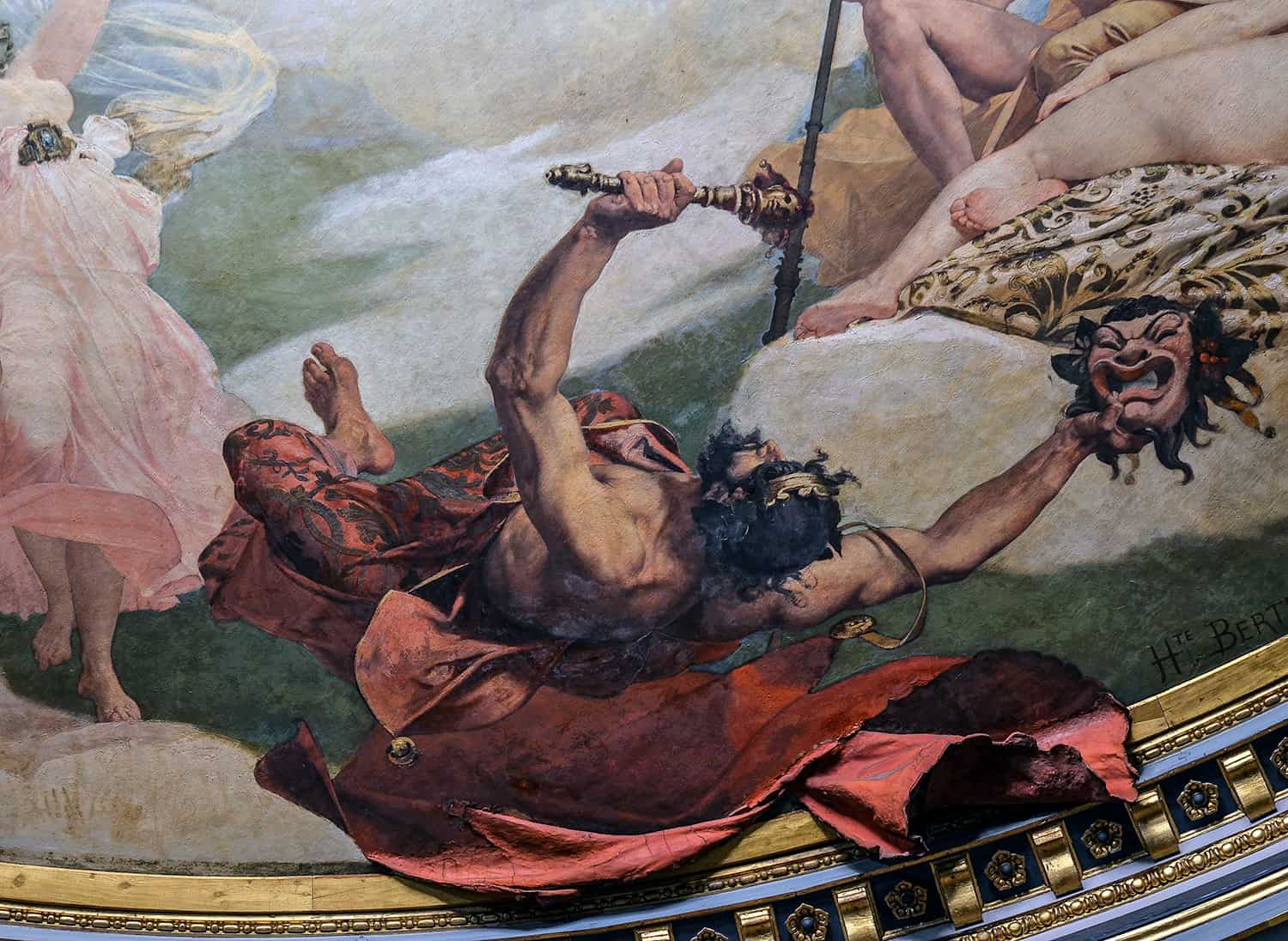

Homer further distinguishes between deceptive dreams and true dreams. However, it is not the case that deceptive dreams are mere illusions and dreams sent by the gods are always true dreams. The gods also employ deceptive dreams. For instance, when Zeus plans to prompt Agamemnon into a premature battle, he sends him a deceptive dream in the form of the wise advisor Nestor. Plato criticizes this passage, arguing that, despite one’s appreciation for Homer, depicting the god Zeus as a sender of false dreams cannot be endorsed.

Aesop explains in a fable how it came to be that the gods did not only send true dreams to humans.

Apollo once asked Zeus for the gift of infallible prophecy. When the gift was granted and Apollo became the greatest prophet among the gods, he became even prouder than before, leading Zeus to seek a remedy.

Zeus created true dreams so that humans could foresee the future in visions without Apollo’s help.

When Apollo apologized and begged Zeus not to completely diminish the value of prophecy through true dreams, Zeus created false dreams. As people realized that some dreams were only illusions, they turned back to Apollo’s oracles.

According to Homer, true and false dreams can be distinguished based on the gate:

For, as they say, there are two gates of vain dreams:

One made of ivory, the other crafted from horn.

Those who come through the gate of ivory,

They deceive the mind with deceitful proclamation;

Others, emerging from the gate of polished horn,

Indicate reality when they appear to humans.

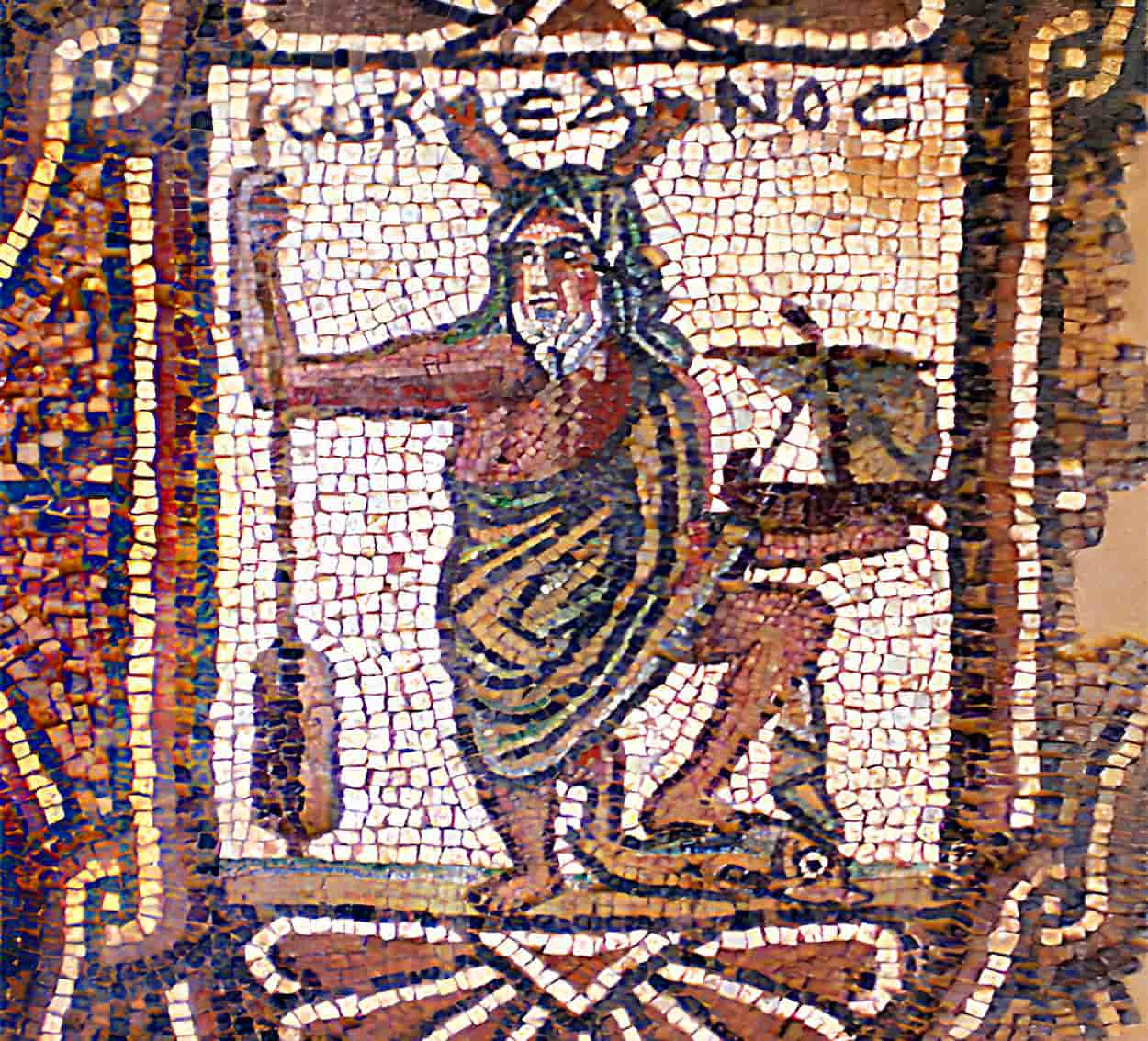

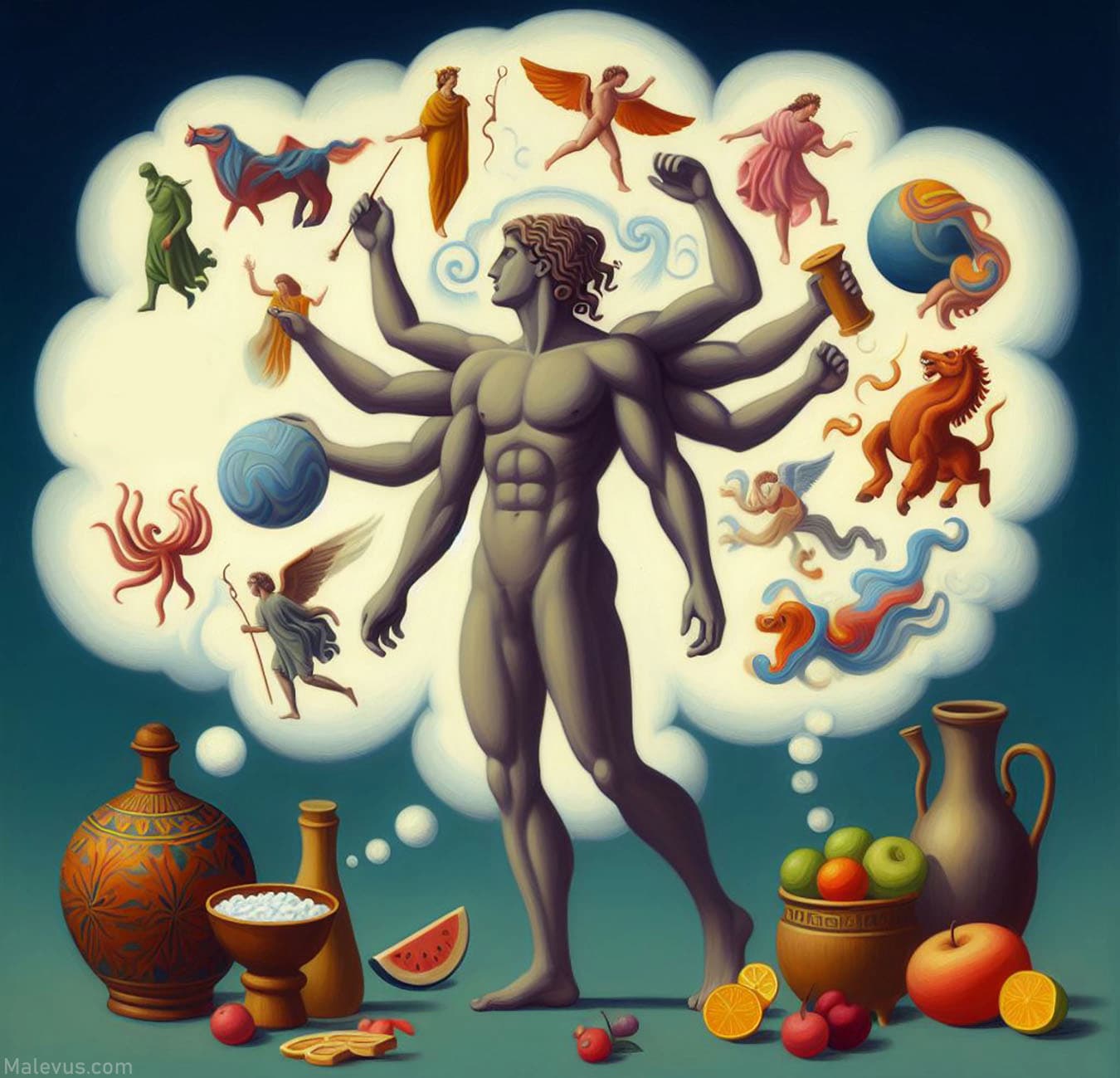

The image of the two gates of dreams (pylē oneirōn) had a broad impact on poetry and iconography. According to one of Flavius Philostratus’s descriptions, the famous Amphiareion of Oropos is the subject of a painting. In this sanctuary, especially the sick, they sought clues for therapy in dreams (see Enkoimesis). The image accordingly depicts the city of Oropos as a youth amidst the Thalattai, allegories of the seas, as well as the gate of dreams, next to which stands the white-clad Aletheia, the goddess of truth, indicating that at this place, the sleeper finds the truth in the dream. The dream (Oneiros) is also depicted, carrying a horn in its hands.

Dreams in Roman Mythology

In Roman mythology, the equivalent of the Greek Oneiros is the Somnia, also children of Nox (Night). Hyginus Mythographus names Erebus as the father of the Somnia.

Ovid mentions Somnus as the father of dreams. In the Metamorphoses, he recounts a thousand sons of Somnus, including Morpheus, Phobetor (or Ikelos), and Phantasos. Morpheus is the most powerful among them, shaping human actors in dreams. Phobetor is responsible for the representation of animals. Phantasos, on the other hand, shapes everything inanimate, such as earth, stones, water, and trees. While the nameless Oneiros send their dreams to the people, Morpheus, Phobetor, and Phantasos undertake this task for kings and tribal leaders.

Personifications of Dreams

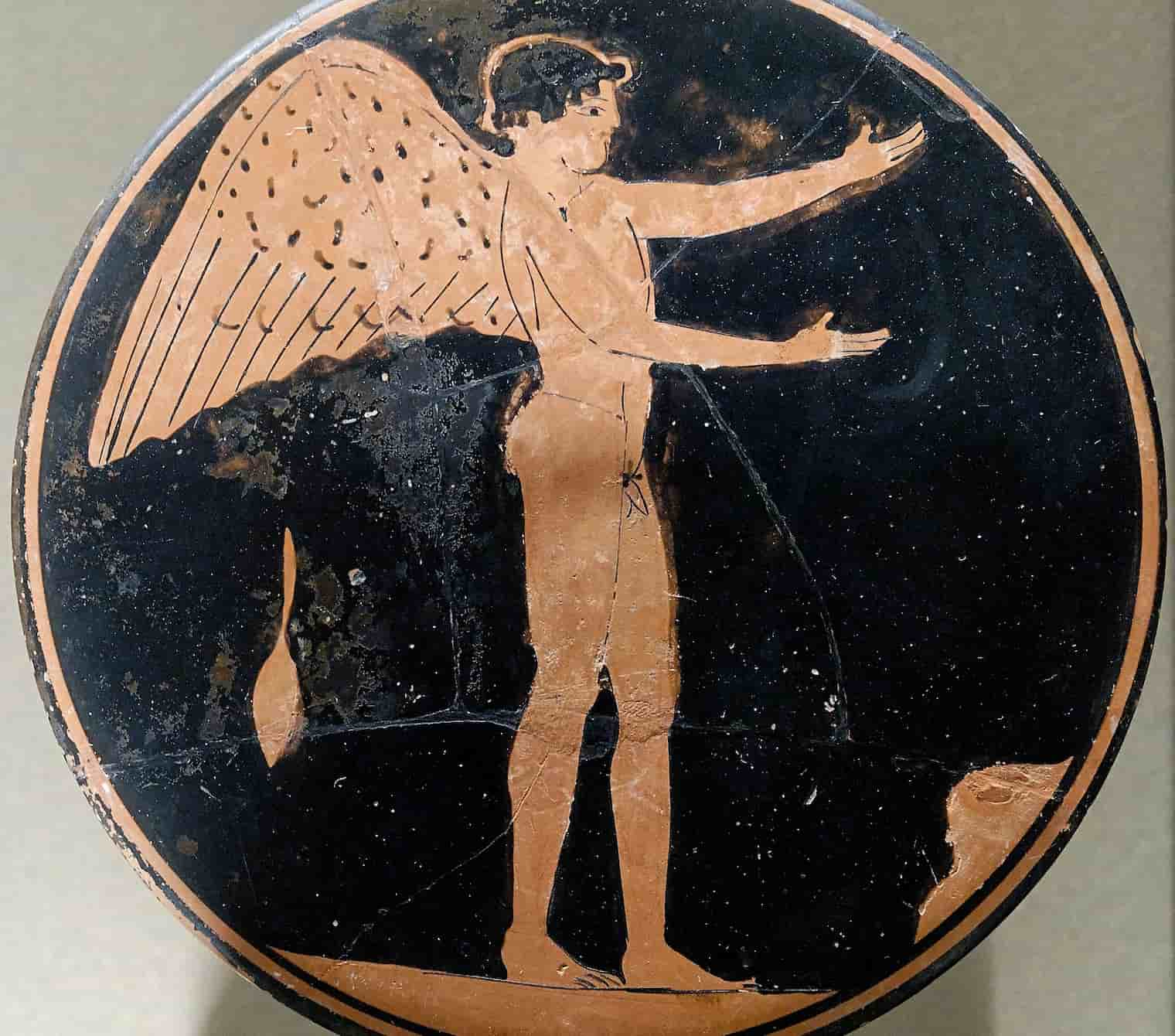

In Greek mythology, the Oneiros were the thousand personifications of dreams. Hesiod considers them children of Nyx (Night) without male intervention, although certain authors regard Erebus (Darkness) as their father. Euripides regarded them as children of Gaia (Earth) and envisioned them as demons with black wings. Ovid, who considers them children of Hypnos (Sleep), mentions three by their names: Morpheus (the most famous and considered by some as their leader), Phobetor (or Icelus), and Phantasos:

“But the father, from the people of his thousand sons, arouses the craftsman and imitator of forms, Morpheus, not because he more skillfully reproduces the walk, the bearing, and the sound of speech than any other. He also adds the clothing and the most common words for each. But he imitates only men. Another becomes a wild beast, a bird, or a long-bodied snake: Icelus, the highest, whom the mortal crowd calls Phobetor. There is also a third of diverse art, Phantasos. He falsely passes to the earth, to a rock, to a wave, to a log, and to everything void of soul. To kings and generals, he usually shows his face at night; others traverse the towns and the common people. His lord ignores them, and of all the brothers, only Morpheus, who fulfills what the Dream has revealed about the offspring of Tethys, is chosen. Sleep, and again, in a soft languor, he lays down his head and in the deep covering, he shields it.”

According to Homer, the Oneiros lived on the dark shores at the western edge of the Ocean, in a cave of Erebus. The gods sent dreams to mortals from one of the two gates located there: authentic dreams emerged from a gate made of horn, while false dreams made their way through a gate made of ivory.

Three Types of Dreams

It is said that there are three kinds of dreams that float around the bed at the back of this cave of sleep.

- Morpheus: Dream of taking the form of a man

- Phobetor/Ikelos: Dream of taking the form of a beast

- Phantasos: Dream of taking the form of an object