How Did the Opium Wars Impact China?

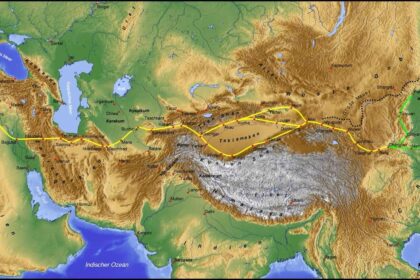

Opium was a significant factor in the Opium Wars. The British East India Company profited from the opium trade by selling opium from India to China. This trade was illegal in China, leading to tensions and ultimately the wars.