- Pauline Einstein was the mother of Albert Einstein.

- She was a talented pianist with artistic interests and was considered well-read.

- She encouraged Albert’s dedication to learning and academic pursuits.

Pauline Einstein (February 8, 1858–February 20, 1920; originally known as Pauline Koch) was the mother of Maja Einstein and Albert Einstein. She was a middle-class woman, and she had a direct effect on Albert Einstein’s upbringing, the education he received in his childhood, and his personal life, including his marriage. She was a talented pianist with other artistic leanings, and she was thought to be well-read. At the address of Badstrasse 20 in Cannstatt, where Pauline Einstein was born, there is a plaque in her honor.

Who Was Pauline Einstein?

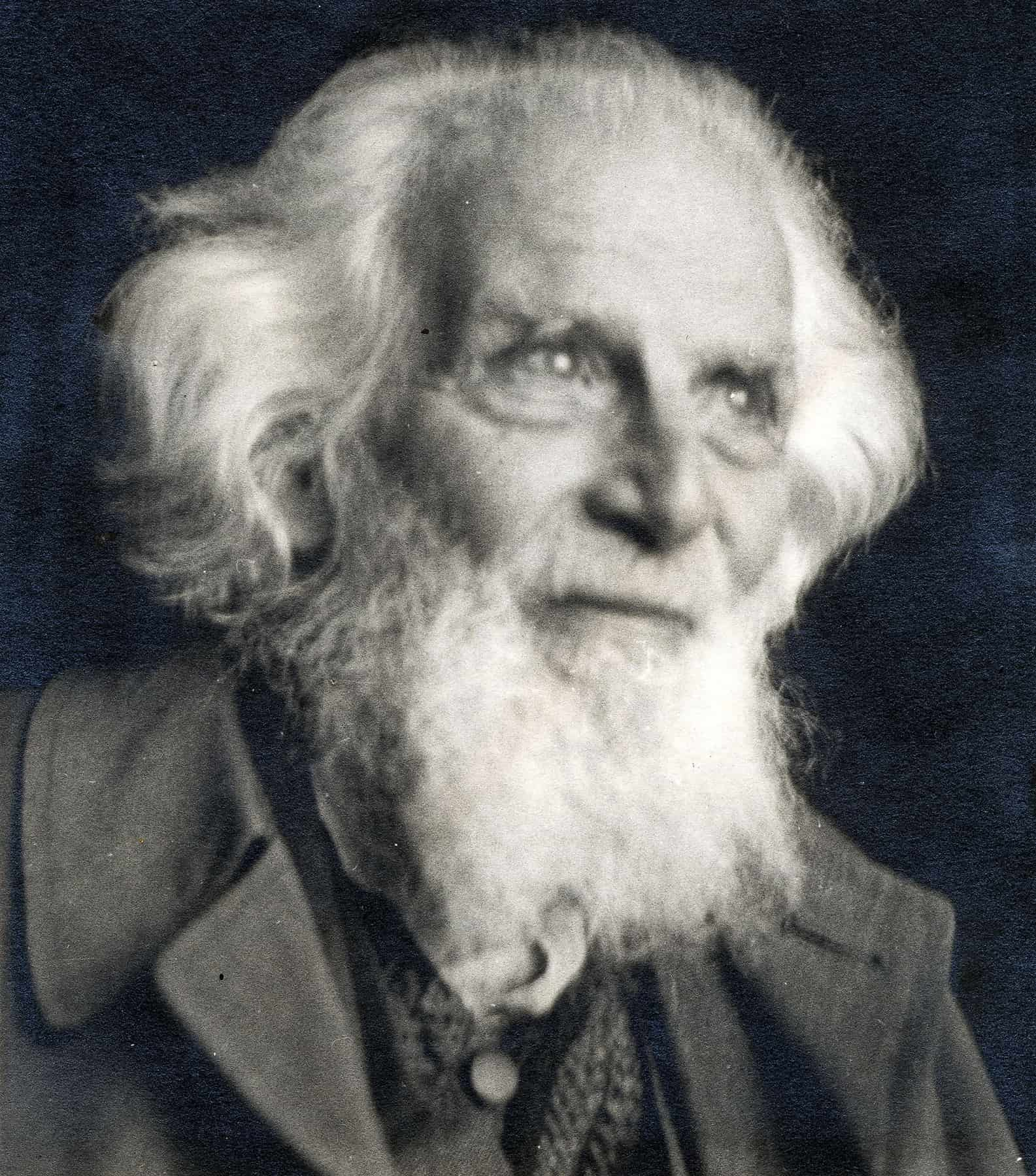

The Cannstatt grain dealer Julius Koch had a daughter named Pauline Einstein. Her dad grew up in a family with modest beginnings. Originally from Jebenhausen, he officially became the supplier of grain to the Royal Württemberg Court after acquiring a sizable fortune with his brother Heinrich. Annette Bernheimer, her mother was a lovely person from the same town.

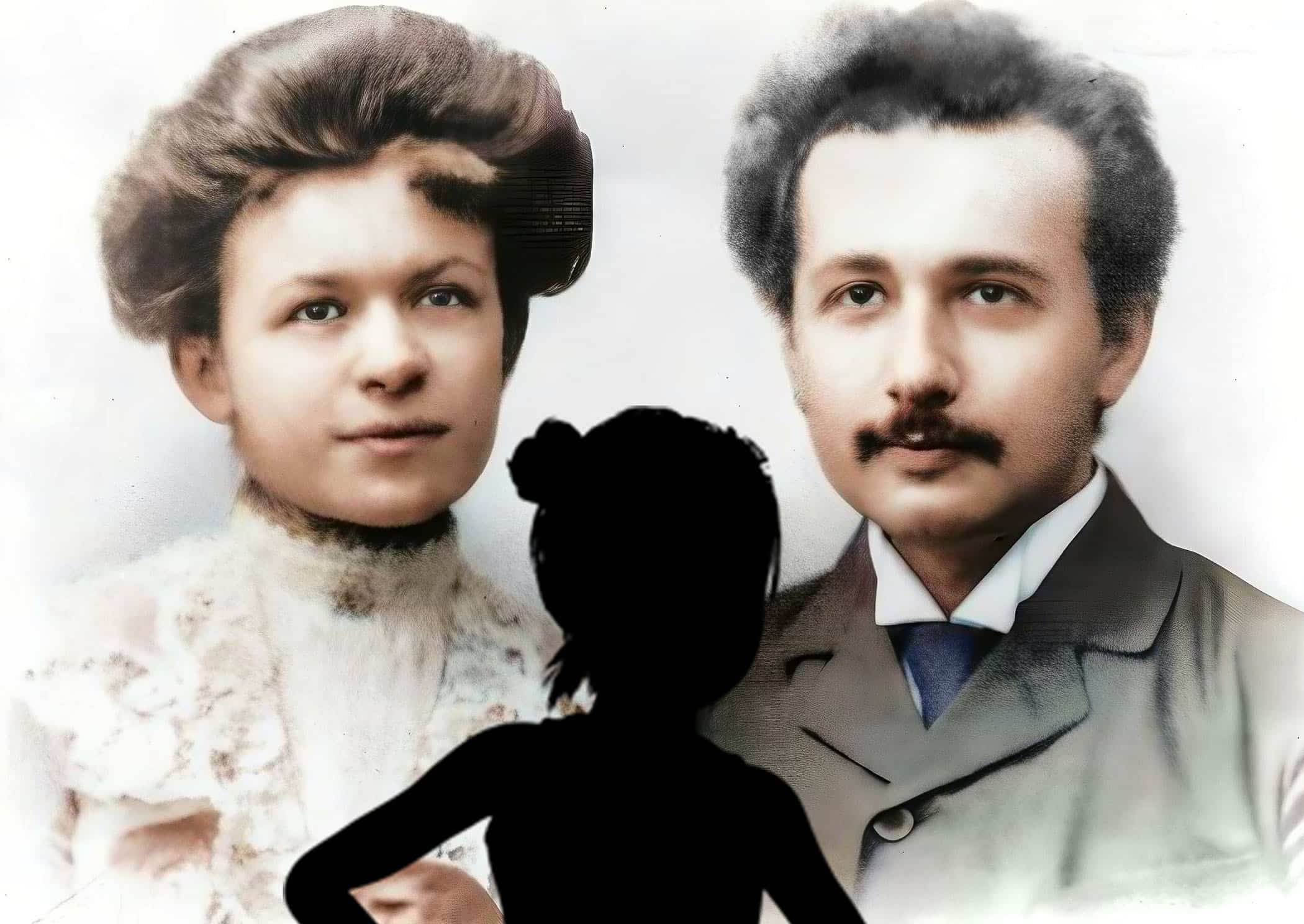

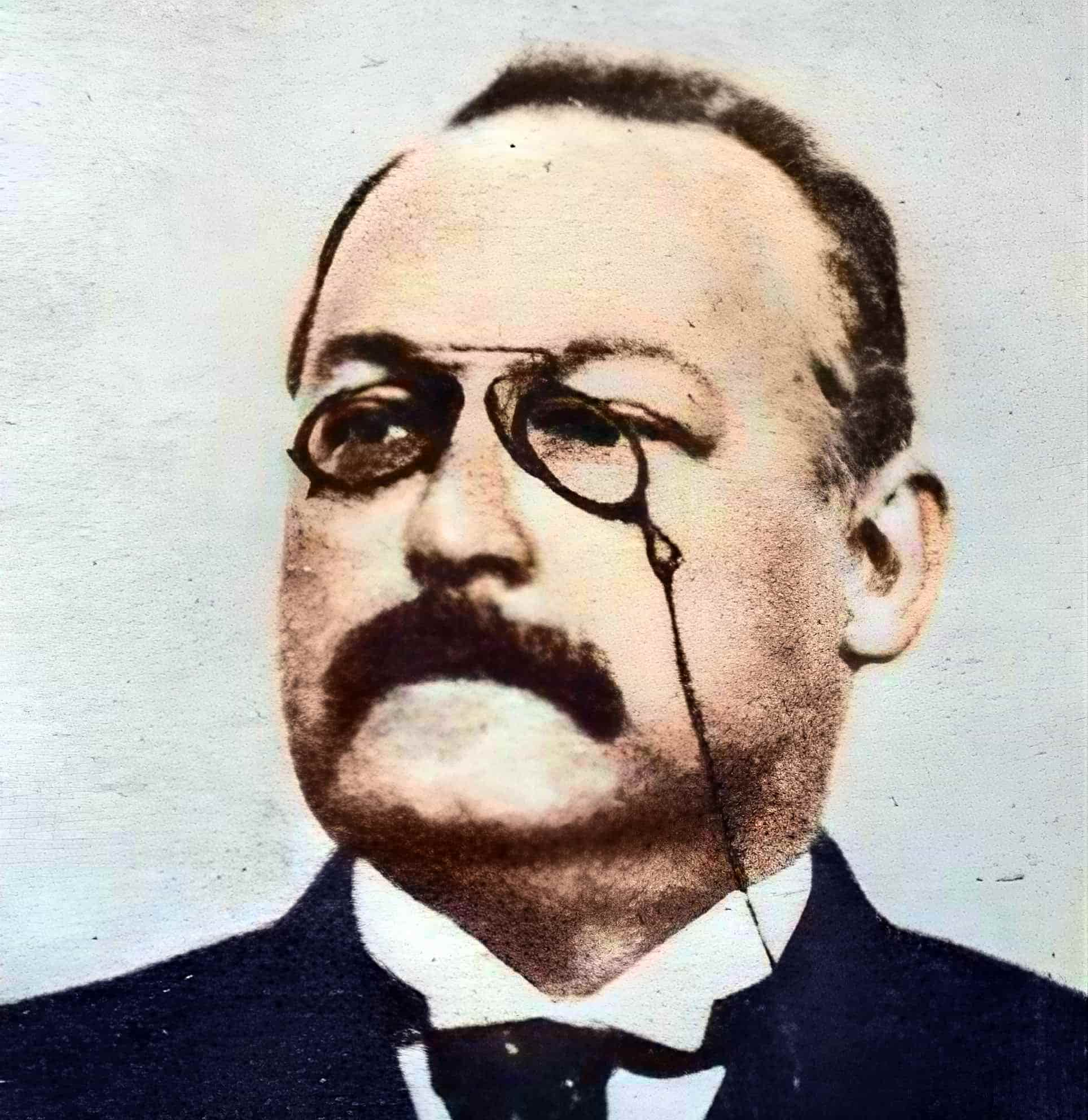

Hermann Einstein (29) and Pauline Einstein (18) tied the knot on June 8, 1876, at an Israelite prayer site in Cannstatt. Hermann was a partner in the Israel & Levi bed feather manufacture in Ulm starting at the end of the 1860s. Pauline, an elegant woman with artistic leanings, was thought to be well-read.

She was a talented pianist and practiced whenever she could find time between her domestic obligations. Maja Einstein often praised her “persevering patience” even while tackling needlework projects. According to Maja, Pauline was a compassionate mother, yet she often did not let her emotions run wild.

Pauline and Hermann Einstein

Pauline and Hermann Einstein resided in a Wilhelminian-style home at Bahnhofstrasse 20 in Ulm, which had been constructed by two Jewish owners. They stayed in this house between 1878 and 1880. When the Einsteins lived in Ulm, they became “dear friends” with Jewish banker Gustav Maier. Hermann Einstein joined his younger brother Jakob’s business in Munich in June 1880; by 1885, the firm had been reorganized as an electrical engineering plant.

There were four generations of Einsteins in the household at Adlzreiterstrasse 14: Hermann and Pauline, Albert and Maja, Jakob and Ida, and Robert and Edith. From 1886 until 1894, Pauline’s father, Julius Koch, a widower, lived with her and her husband’s families in Munich. However, as a result of financial difficulties, the Munich business was shut down in 1894, and the family relocated to Milan.

How Did Pauline Raise Albert as a Kid?

Pauline Einstein achieved ‘self-actualization’ as a mother and wife when she understood the full potential of her brilliantly talented child, Albert Einstein. This was at a time when, as the wife of a business owner, she was legally barred from working outside the home. At the age of five, Albert Einstein was already in the second grade of his Munich primary school because his mother Pauline had given him individual lessons.

Albert Einstein’s ‘religious period’ began when he was 10 years old and lasted for two years. During this time, he was strict with his family about not, among other things, eating kosher. However, shortly after that, Albert developed an agnosticism toward everything. Lucky for him, his parents let him out of having a bar mitzvah, unlike most other Jewish families.

A Jewish medical student from Munich named Max Talmey (1869–1941) was invited once a week by Pauline Einstein to have dinner at the house. The natural world and the fundamentals of philosophical and mathematical-scientific thought were both new to Albert before he met Talmey.

Pauline Einstein’s Legacy on Albert

Pauline Einstein instilled in her son Albert a desire for learning, hard work, and dedication until his death in 1894. She urged Albert to study the violin with all his might. Beginning at the age of twelve, Albert found that his violin playing provided him with inspiration in his life, including in the field of physics.

Having received parental permission, Albert studied independently in Milan in order to pass the admission test for the Swiss Federal Polytechnic (ETH) in Zurich. With dedication, Pauline Einstein fostered her son Albert’s growth. She was typical of the mother who sees her role as ensuring that her talented child grows into an accomplished person.

A Nobel Prize was awarded to Albert in the end. On the other hand, Maja Einstein, the daughter, earned a doctorate in the field of Romance studies.

A Turbulent Life

Together with Lorenzo Garrone, Jakob and Hermann Einstein ran an electrical engineering enterprise in Pavia, Italy, from 1894 until its failure in 1896. Hermann Einstein eventually went on to run his own, smaller electrotechnical businesses in Milan. The first one collapsed into insolvency, leaving just the second one standing. In 1895, Albert’s parents realized they couldn’t afford to keep him in Zurich for school, so they transferred him to Genoa instead.

There, Albert lived well thanks to his aunt Julie Koch, who provided him with 100 Swiss francs a month until the year 1900. Pauline Einstein was her sister-in-law and a close friend. So, Pauline Einstein made sure her kids had enough money to get by, even though they were practically poor. Pauline Einstein even took her kids, Albert and Maja, to Mettmenstetten (a village in Switzerland) twice over the summer at the request of Julie Koch.

For Pauline and Hermann Einstein, keeping their independence intact was a top priority from 1896 until 1902. After Hermann Einstein’s untimely death from heart disease on October 10, 1902, Pauline Einstein found herself a widow.

The Second Act in Pauline Einstein’s Life

After spending some time with her cousin Auguste Hochberger in Heilbronn, Germany, Pauline Einstein relocated to Hechingen in 1903 to be closer to her sister Fanny, and brother-in-law Rudolf Einstein. In 1910, the Einsteins brought Pauline with them to Berlin.

However, in 1911, she was unable to remain there due to financial problems, so her son Albert sent her to work as a housekeeper for the wealthy Heinz Oppenheim in Heilbronn. In Heilbronn, Heinz ran a spice and intestinal import business.

Albert Einstein intended to go into electrical engineering and could have helped the family firm get off the ground in 1900 if he had taken that path. When the school year at Aarau was over, however, he decided to delve into the study of physics and mathematics. The Einsteins were opposed to their son marrying a non-Jewish student at Zurich University named Mileva Maric, a Serb who graduated as one of the first women in mathematics and physics. Their marriage occurred in 1903, when Maric was 28 and Einstein was 24.

Mileva Maric was now Pauline Einstein’s daughter-in-law, although she despised her since she was older than her son and neither Jewish nor German. “Like you, she’s a book, but you ought to have a wife,” Pauline said to Einstein. “By the time you’re 30, she’ll be an old witch.”

Since they were living in Zurich, Pauline was unable to maintain communication with the couple. She was certain that she could tell her son, better than he could, which lady was the right one for him. Nonetheless, both women stopped speaking to each other in 1913.

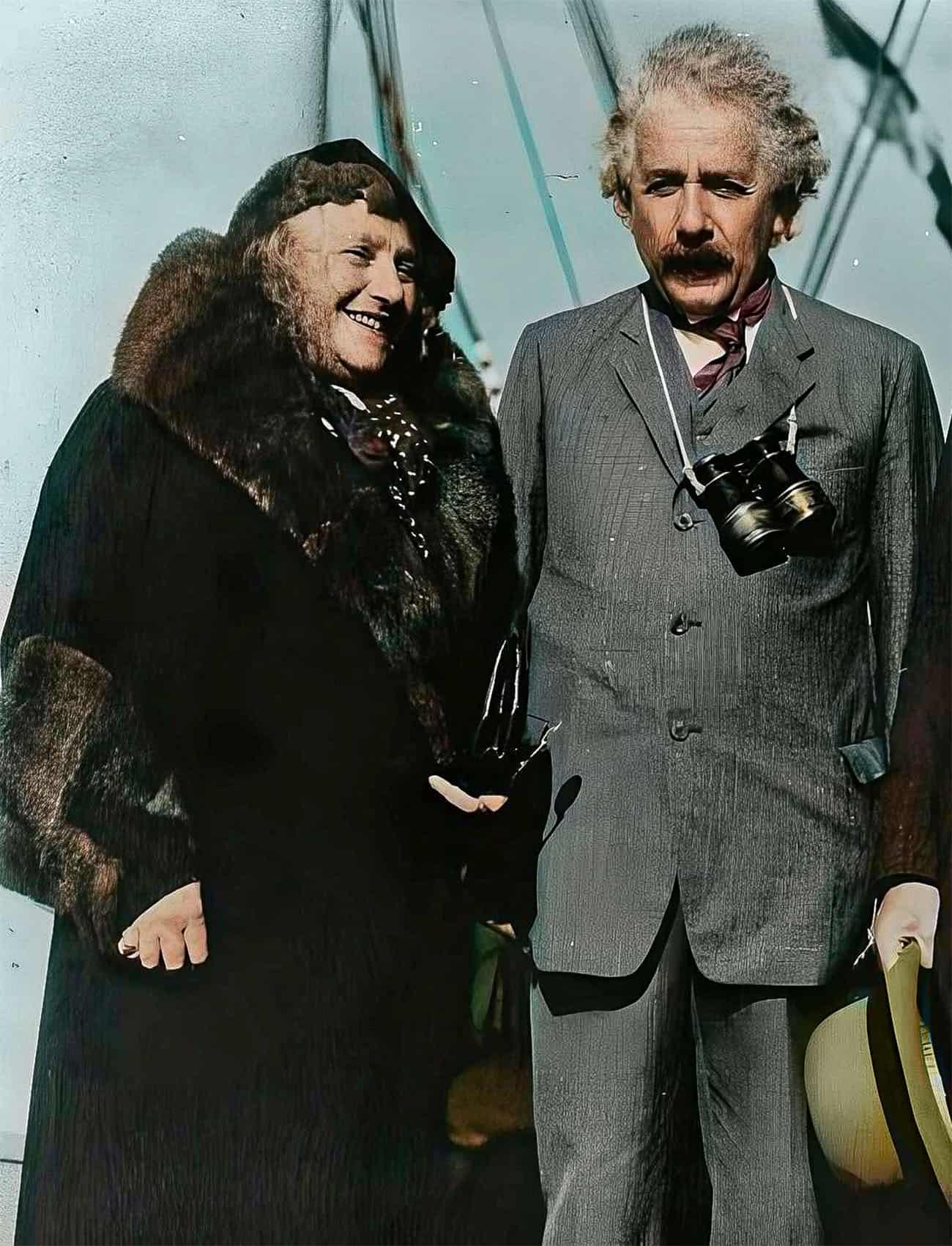

Finally, a Worthy Bride

His mother was finally at peace with Einstein’s separation from Mileva Maric and her children in 1914 and his divorce from her in 1919, but only after Albert established a relationship with his Jewish cousin Elsa Einstein in Berlin. In July 1914, Pauline Einstein won the battle for Mileva’s separation from the Berlin house when Albert sent his wife and her children back to Zurich.

Even though Elsa was older than her son, Albert Einstein’s mother nevertheless gave her blessing to their relationship in 1912. This was because Elsa was Jewish and had previously been accepted into the family. In 1914, Pauline Einstein went back to Berlin to take care of her oldest, recently widowed brother Jakob Koch’s family.

Her Final Years

“I know what it’s like to see one’s mother go through the agony of death and be unable to help; there is no consolation.”

Einstein on his mother.

Pauline had surgery in Berlin the same year, 1914, to treat uterine cancer; Albert Einstein footed the bill. From 1915 through 1918, Pauline Einstein worked as Heinz Oppenheim’s housekeeper in Heilbronn once more. Pauline kept working as a housekeeper even as a cancer patient, probably because Einstein was working at the Patent Office and he was trying to support his family on his modest income.

In 1918, she visited her older brother Jakob Koch in Zurich for a while. Her condition worsened again in 1919. At the time, Pauline was residing in a Lucerne (Switzerland) nursing facility, which she had first moved into with her daughter Maja Einstein and her husband Paul Winteler.

With the help of a doctor from Lucerne, a nurse, and Pauline Einstein’s daughter Maja, she was transported to Berlin in a special hospital vehicle in the winter of 1919. For her last two months on earth, she was attended to by the nurse from Lucerne under the roof of her son Albert in Wilmersdorf.

On February 20, 1920, only weeks after turning 62, Pauline Einstein passed away; she was laid to rest the following day, on February 23, in the Schöneberg Municipal Cemetery on Maxstrasse, Berlin. In modern times, she was featured in the 2017 TV series “Genius.”

References

- Featured Image: Find a Grave Memorial, upscaled and colorized.

- NYTimes – Essay Dollie and Johnnie

- Einstein in Love – Google Books

- The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein: The early years, 1879-1902 – Google Books