Pausanias (Ancient Greek: Παυσανίας; b. 447 BC–d. 385-84 BC, Tegea, Arcadia, Greece) was a Spartan king from the Agiad dynasty (Royal Spartan dynasty), the son of Pleistoanax. He ruled during his father’s exile from 445 to 426 BCE (under the guardianship of his uncle, Cleomenes) and after his father’s death from 409 or 408–07 to 395 BCE (this time independently). Pausanias commanded the Spartan army during the campaign in Attica in 405 BCE, in the final stage of the Peloponnesian War.

Later, he led the opposition against the overly powerful admiral Lysander, took command of a new campaign in Attica, and succeeded in restoring the democratic regime in Athens (403 BCE). During the Corinthian War, he moved to Boeotia to assist Lysander but did not participate in the Battle of Haliartus, where Lysander was defeated and killed (395 BCE). Because of this, Pausanias was sentenced to death in absentia; he fled to Tegea, where he later died.

In exile, Pausanias wrote a speech about the laws of Lycurgus, in which, according to one version, he proposed abolishing or limiting the powers of the Spartan institution of the ephorate. His sons were the Spartan kings Agesipolis I and Cleombrotus I. In historiography, Pausanias is associated with the restoration of the democratic system in Athens and Sparta’s abandonment of an expansionist foreign policy throughout Greece, a policy advocated by Lysander. Scholars’ opinions on whether Pausanias was a principled opponent of tyranny or simply fought against Lysander for influence differ.

Pausanias’ Origin and Early Years

Pausanias belonged to the Agiad dynasty, one of the two royal houses of Sparta, tracing their lineage back to the mythological hero Heracles. He was the son of King Pleistoanax and the grandson of Pausanias, the regent during the reign of King Pleistarchus, who defeated the Persians at Plataea (an ancient Greek city-state) in 479 BCE.

Pausanias’s birth date is unknown. The German researcher H. Schaefer suggested that the future king might have been born shortly before 447 BCE. In 445 BCE, Pleistoanax was suspected of taking bribes from Athens, Sparta’s wartime adversary at the time, and was sentenced to a massive fine. He went into exile, and the royal authority passed to his son.

Due to Pausanias’s youth, he was placed under the guardianship of his uncle, Pleistoanax’s brother Cleomenes, who led campaigns and served as the high priest. In 426 BCE, Pausanias’s father returned to Sparta and was reinstated. After his father’s death in 409 or 408–07 BCE, Pausanias once again became king.

His First Campaign in Attica

When Pausanias finally came to power, Sparta and its leading Peloponnesian League were once again at war with Athens. In 405 BCE, the Spartan admiral Lysander destroyed the Athenian fleet at Aegospotami. This marked the first surviving accounts of Pausanias: the king led an army, including Spartans and other Peloponnesians (except the Argives), besieging Athens jointly with Lysander and his co-ruler Agis II from the Eurypontid dynasty.

The assault did not succeed, and the kings withdrew to winter quarters. Only the fleet remained to block Piraeus, cutting off supply routes. The next year (404 BCE), the Athenians agreed to peace: they dissolved their maritime alliance, demolished the Long Walls, recognized Spartan hegemony, and saw a pro-Spartan oligarchic government established in their city, later known as the “Thirty Tyrants.”

In the final years of the war, Lysander became the most influential politician in Sparta. By supporting tyrannical regimes in various Greek cities, he effectively established his executive authority system, posing a threat to the Spartan political structure. Opposition to this figure emerged, led by Pausanias. According to Xenophon and Diodorus Siculus, the king envied Lysander, but scholars are willing to consider that Pausanias had principled considerations—such as the desire to save his homeland from turmoil and improve its reputation among other Hellenes.

He openly opposed Lysander in 403 BCE, during the civil war unfolding in Attica. By then, the “Thirty Tyrants” had sought refuge in Eleusis (the city in Athens), democracy supporters were entrenched in Piraeus, and another oligarchic government—the Board of Ten—emerged in Athens. Both oligarchic regimes sought help from Sparta, and Lysander went to Attica with the authority of the harmost, initiating the formation of a mercenary army. In the case of success, he could have become the independent ruler of Athens, which his opponents could not tolerate.

Pausanias proposed sending a Spartan expedition to Attica, which was to be led by one of the kings. Thanks to the support of Agis and three out of five ephors, this proposal was accepted, and Pausanias received the command and authority to rectify Athenian affairs. Plutarch writes that, to achieve his goal, the king declared his intention to continue Lysander’s policy of “assisting tyrants against the people.” Subsequent events revealed that this was a clear deception: Pausanias, merely for appearances, attacked the Piraeus Democrats, after which he organized negotiations between them and the Board of Ten regime. The parties reconciled, burying recent disputes and the crimes associated with them.

Overall, Pausanias’s policy in Attica was decidedly anti-tyrannical. This was linked to the king’s sympathy for the Piraeus democrats and their leader Thrasybulus, his reluctance to “strengthen the tyrannical power of impious people, covering Sparta with indelible disgrace” (words of geographer Pausanias), and the desire to weaken Lysander’s position. The latter was forced to yield to the king, who held a higher position in the military hierarchy and enjoyed the support of the ephors.

The navarch was excluded from the negotiation process, Pausanias compelled the members of the Board of Ten to leave Athens, and in 401 BCE, Attica was reintegrated under the rule of a democratic government. This signaled Sparta’s demonstrative abandonment of an expansionist policy and could be interpreted as a conciliatory gesture toward allies.

Trial and the Corinthian War

Lysander could not easily accept defeat. According to one version, it was at his initiative that, upon his return to Sparta, Pausanias was brought to trial on charges of treason. The pretext for the lawsuit was the death in battle against the Piraeus democrats of several high-ranking Spartiates, including two polemarchs. Presumably, the trial took place in the winter of 403–402 BCE.

Half of the sitting gerontes (14 out of 28, “gerousia”) and King Agis supported the accusation (possibly due to Pausanias’s violation of agreements made by the kings before the Attic campaign), but the votes of all ephors and the second half of the gerontes ensured an acquittal. Historians see in this almost equal division of votes confirmation of Lysander’s immense influence and the split of the Spartan elite into several roughly equal power blocs. To better understand Pausanias’s trial, the ephors usually supported weak kings.

Nothing is known about the king’s involvement in events over the following years. In particular, surviving sources do not report whether Pausanias commanded campaigns in Elis undertaken by the Spartans in 402-400 BCE (H. Schaefer considers this command quite probable). In 399 BCE, when Agis II died, Pausanias intervened in the dispute over the royal title, claimed by the deceased’s son and brother, Leotychidas and Agesilaus, respectively.

Leotychidas was considered the son of Queen Timaea by Alcibiades, but Agis, before his death, acknowledged him as his blood son; nevertheless, Agesilaus asserted his right to power as the uncontested Eurypontid. Since he was a friend of Lysander, Pausanias supported Leotychidas but suffered defeat; Agesilaus became king.

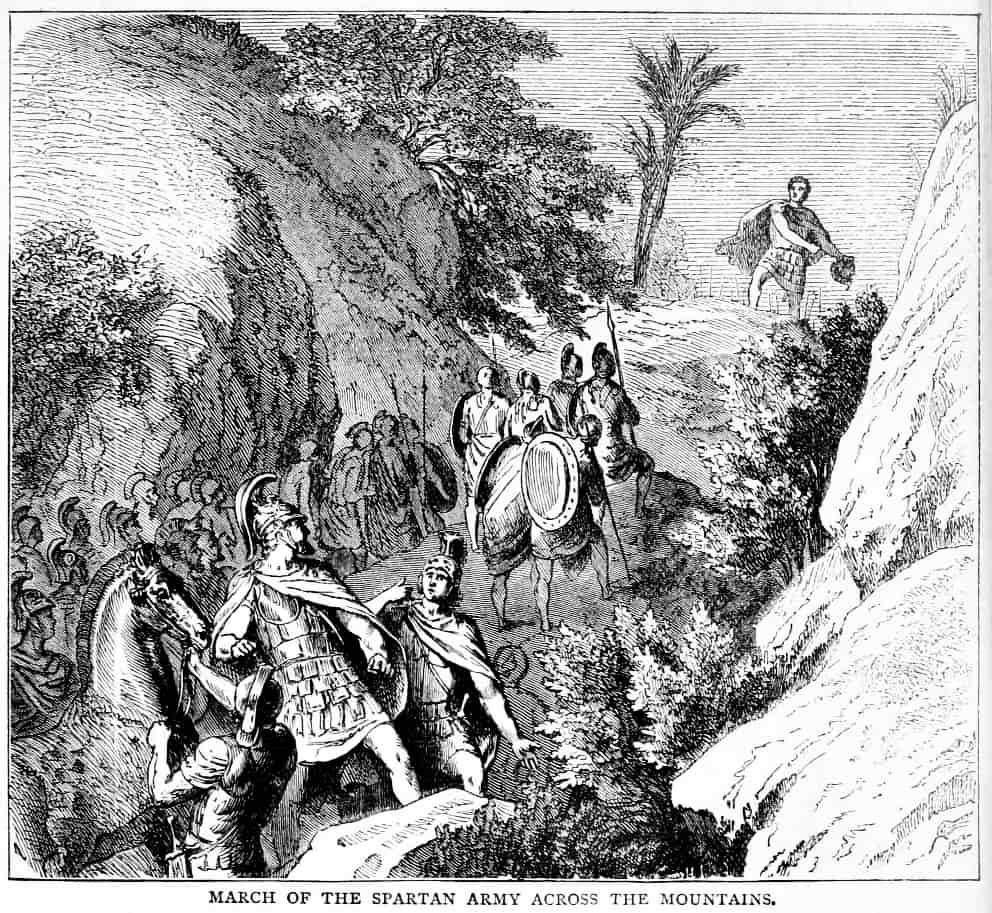

In 395 BCE, the Corinthian War began, during which Athens, Argos, Thebes, and Corinth joined forces against Sparta, receiving support from Persia. In Sparta, it was decided to send two armies into Boeotia, commanded by Lysander and Pausanias. They were supposed to unite near the city of Haliartus either according to a pre-arranged plan or based on a letter sent by Lysander to Pausanias during the campaign but ended up in the hands of the enemy. In any case, the meeting did not take place. Pausanias, according to one version of ancient tradition, delayed on the way to Arcadian Tegea, awaiting reinforcements from allies.

Lysander, at Haliartus, attempted to take the city by storm without waiting for the king or immediately clashed with the Theban army; in the battle, the Spartans were routed, and their commander perished. Pausanias, appearing at Haliartus a day later, chose not to engage in battle. When the Athenians came to aid the Thebans, the king negotiated a truce with the enemy, receiving the bodies of the fallen Spartan warriors in exchange for a commitment to leave Boeotia. According to Xenophon, during the retreat, “the Spartans were disheartened, while the Thebans treated them extremely arrogantly, forcing anyone who deviated even a step from the road onto someone’s land to return to the road under blows.”

In Sparta, Pausanias faced trial once again. He was charged with the delay at Haliartus, concluding a truce instead of attempting to retrieve the bodies from the enemy, and excessive leniency towards the Piraeus Democrats, displayed eight years prior. The king did not appear at the trial. He was sentenced to death, but before the decision was finalized, Pausanias fled to Tegea. Presumably, the trial and the harsh sentence were concessions by the Spartan elite to numerous supporters of Lysander. However, apparently, no one wanted to execute the king, so he managed to escape. The royal power passed to Pausanias’s elder son, Agesipolis, with his closest relative, Aristodemus, becoming his guardian.

Later, rumors circulated in Greece that Pausanias intentionally delayed Haliartus to harm Lysander.

Pausanias in Exile

Pausanias spent the following years in the city of Tegea in Arcadia, not far from the borders of Laconia. According to Plutarch, he lived “as a suppliant for protection on sacred land belonging to Athena.” Apparently, no one attempted to bring the former king back to his homeland and enforce the sentence. Pausanias must have retained many influential supporters, and his execution could have destabilized the situation in Sparta.

Xenophon mentions Pausanias in connection with the events of 385–384 BCE when Agesipolis undertook a campaign against the neighboring city of Mantinea, near Tegea. After the surrender of the city, 60 of its citizens, “supporters of the Argives and leaders of democracy,” faced the death penalty, but Pausanias persuaded his son to settle for exile. Xenophon notes that the former king “was on very friendly terms with the leaders of the Mantinean democracy,” and historians highlight Pausanias’s sympathies towards Democrats in various situations.

During this period of his life, the former king turned to literature. Strabo cites information on this subject from the Ephor of Cyme: “Pausanias, after being exiled due to the hatred of the Eurypontids—the other royal house—composed a speech on the laws of Lycurgus (who belonged to the house that expelled Pausanias); in this speech, he talks about the oracles given to Lycurgus regarding the majority of laws.” The text has survived in corrupted form, and the words “due to hatred” are an editorial insertion made for clarity. In the late 19th century, another version of Strabo’s text was discovered, indicating that Pausanias composed a speech “against the laws of Lycurgus.”

Researchers’ opinions on the correctness of this formulation and the political orientation of the exile’s composition differ. Karl Julius Beloch was confident that Pausanias could not criticize the laws of Lycurgus, revered by contemporary Sparta, as his goal in writing the speech was to obtain permission to return home. Eduard Meyer believed that these laws corresponded to the character of the king, and he did not criticize but defended them: “From the state that sent him into exile and trampled the old order, he appealed to the legislator to whom this state owed its power.”

Supporters of the hypothesis of criticism of the laws refer to Aristotle’s account in “Politics.” “Sometimes a coup aims to make only partial changes in the state structure, for example, to establish or abolish some position. Thus, according to some, in Lacedaemon, Lysander tried to abolish the royal power, and King Pausanias—the ephorate.” These words may imply that Pausanias had a critical view of the Spartan political system and proposed either to eliminate the authority of the ephors as tyrannical or to subordinate this institution to the kings. However, many researchers are convinced that Aristotle is not talking about King Pausanias but his grandfather. The former king died in Tegea from an illness, apparently shortly after 385–384 BCE.

Pausanias’ Family

Pausanias had two sons, Agesipolis I and Cleombrotus I, who reigned in Sparta from 396 to 380 and 380 to 371 BCE, respectively. The name of their mother is unknown. H. Schaefer dates the birth of Agesipolis to around 410 BCE, and Pausanias’s marriage, accordingly, a short time before that.

Sayings attributed to Pausanias, as recorded by Plutarch:

- When Pausanias, son of Pleistoanax, was asked why the Spartans do not allow changes to ancient laws, he replied, ‘Because laws should dominate over people, not people over laws.’

- Banished from Sparta and residing in Tegea, Pausanias still praised the Lacedaemonians. Someone asked him, ‘Why did you not stay in Sparta and flee from there?’ ‘Because,’ replied Pausanias, ‘physicians are usually found not near the healthy but near the sick.’

Evaluations of Personality and Activities

Researchers note that in 403 BCE, Pausanias saved Athenian democracy. There is no consensus on his motives. E. Meyer sees Pausanias as a principled opponent of tyranny, stating, “Sparta’s behavior towards Athens is the most glorious page in its history. For this, Athens, just like the whole world, must thank the most worthy king from the Agiad house.” Sometimes, this judgment is characterized as somewhat idealized. L. Pechatnova poses a rhetorical question:

“How can we know whose side the king would have taken if Lysander had supported the Piraeus democrats instead of the tyrants of Eleusis?” This same researcher sees Pausanias as the representative of the interests of “the moderate, if not conservative, part of Spartan citizenship, which opposed the creation of the Spartan state as conceived and organized by Lysander.” This “faction” was likely advocating for the withdrawal of Spartan garrisons with harmosts from other poleis, a return to traditional foreign policy, and a limitation on the influx of money into Sparta from other regions, which threatened a future split within the community.

As a hypothetical author of a reform program, Pausanias could be placed alongside his opponent Lysander. Both proposed changes to the political structure of Sparta, but the navarch was too radical and the king was too conservative. Neither could garner the support of the majority of citizens. With the death of Lysander and the condemnation of Pausanias, another stage in the internal political struggle in Sparta came to an end. The victor was Agesilaus, who combined strengthening the authority of the royal power with expansionism in the spirit of Lysander.