Pericles was an Athenian statesman and strategist who lived from 495 to 429 BC. Pericles, the uninterruptable military leader of Athens from 443 to 431 BC, who also happened to be the period’s namesake, was the undisputed star of the 5th century. The city was the political center of all of Greece, and it was also home to some of the country’s finest artists and thinkers. Moreover, Athens boasted lavish buildings like the Parthenon thanks to the Delian League‘s riches, which helps to explain why it is considered the most beautiful city in Antiquity. During the Peloponnesian War, while his city was under siege by Sparta, Pericles died of the plague in 429, at the age of 65.

Who was Pericles?

Former Greek statesman Pericles (493–429 BC). Famous for his oratory talents and meticulous honesty, Pericles ruled Athens for nearly 30 years during the city’s golden age. He was an advocate for learning and the arts and supervised the building of the Parthenon. The years in which Pericles was the leader of Athens, from about 461 to 429 BC, are frequently referred to as the u0022Age of Pericles.u0022 Many people blame Pericles for starting the conflict with Sparta that led to the collapse of Athens. At the age of 65, Pericles died as a result of the disease that ravaged Athens during their disastrous war.

What Pericles was known for?

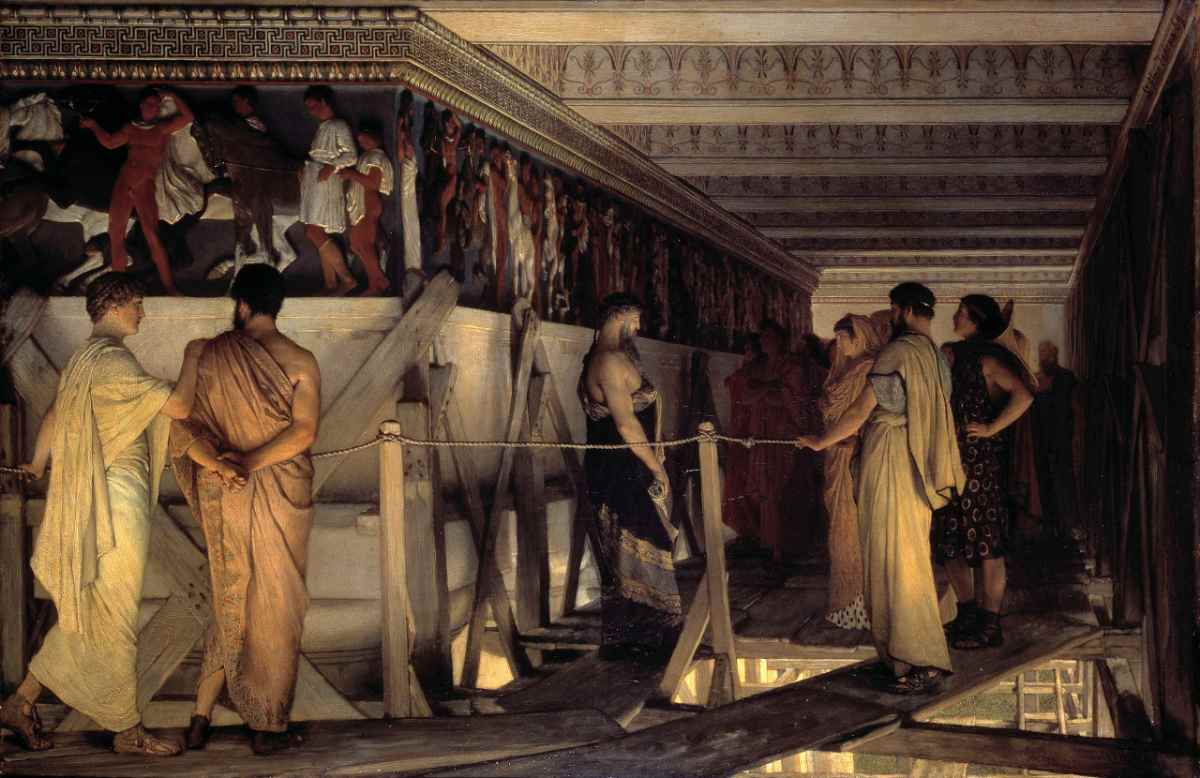

In addition to his leadership of the Athenian Empire and his attempts to promote democracy and the rule of law, Pericles is most recognized for his involvement in the building of the Parthenon, a temple dedicated to the goddess Athena on the Acropolis. His contributions to Athenian culture include patronage of the arts and advocacy of Athenian excellence, for which he is well recognized.

How did Pericles rise to power?

A member of a powerful and well-off family, Pericles benefited from a comfortable upbringing and an excellent education. He entered politics at a young age and rapidly rose to prominence. His charm and persuasiveness made him an effective politician. Also, he was a great orator who often spoke in defense of Athens and its ideals with his persuasive speeches.

Origin of Pericles and his first steps in politics

Around the year 492 BC, Pericles, an aristocratic Athens native, entered the world. His father, Xanthippe, was a member of the democratic party’s leadership and a member of an ancient Attic noble family who helped beat the Persians at the Mycale Cape in 479 BC. He was related to the noble Alcmaeonidae dynasty through his mother, and his great-uncle was the lawmaker Cleisthenes, who was responsible for the toppling of the Pisistratus (or Peisistratus).

Zeno of Elea and Anaxagoras, two of Pericles’ primary philosophers, shaped him as a young man into a rationalist with a bent for action and an interest in the major matters of the city. Despite being “exceedingly reluctant to face the people” (according to Plutarch), Pericles chose to serve the democratic party, perhaps to follow in the footsteps of his relative Clisthenes, or perhaps to feel the lightness of the tiny clans of nobles, which he had attended since boyhood.

His attacks against Cimon, the conservative party leader who would be marginalized after just two years in power, can be traced back to 463. By the time he turned 30 in 461 BC, Pericles had already secured a dominant position for himself in the democratic party and in the city, both of which he ruled with his oratory.

Pericles: The champion of the Athenian democracy

Despite a brief period of eclipse lasting a few months (430–429 BC), he continued to be the primary leader, or “tyrant,” of the Athenian democracy until his death. With his role as strategist being extended every year for almost 30 years, Pericles essentially became the perpetual leader of Athens and a figurehead prime minister. Pericles, who enjoyed widespread support, is credited with advancing Athenian democracy to its fullest potential by expanding public participation in government.

He initiated changes restricting the Areopagus’ authority as early as 462 BC, while he was still merely the deputy of Ephialtes, who was to die shortly after being slain. The third-class citizens (zeugites) were allowed to enter the archontate by Pericles; even the lowest-class citizens (the thetes) were eligible to become archons. Pericles popularized the use of lotteries, which eventually became central to representative government.

Pericles made allowances beginning in 451 for the council of the Five Hundred, for the archons, the judges with the court of the Heliasts, for the strategists (the military generals), and for the participation of the citizens in the various civic festivals. This was called “the misthophoria,” or the inclusion of the poor in the magistratures. Nonetheless, these democratic advances were limited to a tiny fraction of Athens’ population, i.e., the only citizens (approximately 30,000 citizens on a population of 410,000 by the middle of the 5th century).

Solon’s legislation, which extended city rights to boys born of a citizen-foreigner marriage, was severely undermined in 451 when Pericles passed legislation recognizing Athenian citizenship only to those born of two citizen parents.

A great strategist

The imperialist Athens of Pericles existed alongside a society marked by inequality. The Delian League’s allies were subdued; the common treasury was moved to Athens (454); the Athenian ecclesia (the assembly of the citizens) replaced the league council as the league’s directing body; and the uprisings of the allies, especially those of Euboean (446) and Samos (440), were put down harshly. All the efforts to establish Greek dominion over the Aegean and Black Seas were directly spearheaded by Pericles. Later, he commanded a fleet that proceeded to the Crimea and seized Sinope on the coast of Asia Minor (437) after a failed mission to the Gulf of Corinth and northwest Greece (454).

During its rule, Athens fought several conflicts, including the First Peloponnesian War (459–446) against Sparta and Corinth, a catastrophic expedition to Egypt in 454, and a civil war among its own allies. The conclusion of the Greco-Persian Wars and the expulsion of the Persians from the Aegean were brought about by the Peace of Callias (449). While the Thirty Years’ Peace (446–431) between Athens and Sparta was signed, the continuance of Athenian expansion led inevitably to the renewal of hostilities, which erupted in 431 as the Second Peloponnesian War and culminated in Athens’ defeat in 404. At the outset of the fight, Pericles died, but not before seeing the ebbing of the support of the people for whom he had been responsible up until that point.

Fall and death of Pericles

Pericles’ prestige was severely damaged by the war’s early setbacks and the plague outbreak that swept over Athens in 430; he was even sentenced to pay a fine of 50 talents. Despite this, Pericles was re-elected as a strategist in the spring of 429, only to be killed by a plague in the fall which was typhoid fever. He was honored for his role in elevating Athens to its zenith of strength and overseeing the peak of Greek civilization under his watch.

It was in the realm of art that the “Age of Pericles” (460–430) left its most enduring record, while also being the time when Aeschylus’s writings were completed, when Sophocles and Euripides were first performed, when Herodotus visited Athens, and when sophistry was influential. Pericles, who was able to assemble and inspire painters like Phidias, Callicrates, Ictinos, and Mnesikles, oversaw the beginning of the repair of the shrines on the Acropolis damaged by the Persians about 450 BC, using tribute from the allies to fund the project. Athens was considered the “school of Greece” because of the prominence of landmarks like the Parthenon, Propylaea, and Erechtheion.

KEY DATES ABOUT PERICLES

495 BC: Birth of Pericles

The political leader of Greece had a humble beginning in the city of his birth.

461 BC: Revolt of the Helots in Sparta

Sparta, an oligarchic city ruled by the “Equals,” saw a serf uprising led by the Helots in 461 BC. Slaves in the realm of the “Equals,” the helots were treated with more disdain and violence than their counterparts in any other Greek city, yet they shared the same fate of being stripped of all civil liberties and forced to perform menial labor. The “Equals” had fewer people on their side during the uprising, but Athens sent reinforcements. When Sparta refused to help, it made the Athenians felt like fools. The next year, Pericles had the field to himself because Cimon had been shunned. Indications are that the truce between the two cities had been breached.

451 BC: Political reforms in Athens

At this time, Pericles implemented his first crucial policy, and Athens’ political structure appeared to be changing. You would now need a minimum of two Athenians in your family tree to be considered for citizenship in Athens. There was a tightening of controls on the magistrates and the assemblies. A member of a noble family, Pericles rose to prominence in his society.

449 BC: Pericles had the Parthenon built

Pericles pressured Athens into constructing a new temple to the goddess Athena by saying he would pay for it out of his own pocket if the people rejected his plan for its funding. The Acropolis temple had been damaged during the Second Persian Invasion of Greece and was only partially restored. The Parthenon was the first of many similar projects. It was a temple with a frieze that remembered the Panathenaic, which was the biggest religious event in the city. Next came the temples of Propylaea and the Erechtheion.

443 BC: Pericles as strategist

In Athens, Pericles rose to the highest magistracy as a strategist. There were really 10 people in this role, but unlike the other strategists, Pericles would be re-elected year after year for the next fifteen years. Pericles was an original who preferred the company of academics over politicians. He lived through the golden age of Athens and died in 429 BC during a plague epidemic. Defender of democracy, Pericles instituted the “misthós,” which allowed any citizen to engage in politics.

431 BC: Sparta invades Attica

The Spartans reached Attica, the land around the city of Athens, and ravaged it. When the Athenians realized they were outnumbered by the Spartans on the battlefield, their strategist, Pericles, decided to move everyone back within the city walls. After the medieval conflicts, a wall was constructed to defend it. Pericles’ plan was to strike at the beaches of Sparta while his soldiers were in Attica, taking advantage of Athens’ strength at sea.

429 BC: Death of Pericles

Pericles succumbed to the plague pandemic that destroyed Athens. The Peloponnesian War restricted the Athenians behind the walls, and this promiscuity promoted the growth of the illness. Inevitably, the epidemic would wipe out one-third of population. Pericles was not immune to political challenges; he was fined, but he eventually re-elected within a year. The Spartan war lasted until 421 BC. Pericles, the architect of Athenian greatness, passed away in the autumn of 429 at the age of roughly 65.

Bibliography:

- Plato, Alcibiades I. See original text in Perseus program (translation) from Plato (1955). Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 8. W.R.M. Lamb (trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99184-2.

- Kagan, Donald (1974). The Archidamian War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-0889-2.

- Mattson, Kevin (1998). Creating a Democratic Public. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01723-5.

- McGregor, Malcolm F. (1987). “Government in Athens”. The Athenians and their Empire. The University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0269-7.

- Kagan, Donald (1989). The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War.

- Plato, Gorgias. See original text in Perseus program, 455d, 455e, 515e (translation) from Plato (1903). Platonis Opera. John Burnet (ed.). Oxford University Press.