Byzantine philosophy consists of the works and philosophical currents expressed in Greek within the Byzantine Empire, starting in the 9th century and flourishing in the following century until the empire’s fall in the 15th century. Heavily influenced by Aristotelian, Platonic, and Neoplatonic ideas, Byzantine philosophy occasionally blurs with theology. It aimed to be a rediscovery, continuation, and reinterpretation of ancient Greek philosophy in light of the Christian faith as transmitted by the Orthodox Church.

Origin and Definition

Education in the Byzantine Empire

Education was widespread among the Byzantines, with a higher percentage of men and even women, a rare phenomenon at that time, being literate compared to Europe or Arab countries. Primary education (propaideia) was readily available, even in villages, and secondary education (paideia—students aged 10 to 17) was fee-based. It took place in a school where the teacher, sometimes with the help of an assistant, taught the trivium (grammar, geometry, and astronomy) and the basics of the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music) by assimilating texts from classical antiquity.

Higher education typically included rhetoric, philosophy, and law. Its purpose was to train competent officials for both the state and the church, at least until the latter established its own university (Patriarchal School) dedicated to clergy formation. The first institution dedicated to advanced studies was founded in 425 by Emperor Theodosius II (r. 402–450) under the name Pandidakterion (in Byzantine Greek: Πανδιδακτήριον, it was the origin of the University of Constantinople). It comprised thirty-one chairs dedicated to law, philosophy, medicine, arithmetic, geometry, etc., with fifteen taught in Latin and sixteen in Greek.

The Conflict Between Christian Faith and Pagan Philosophy

When Greek elites converted to Christianity and began studying Greek classics, a confrontation between “true philosophy,” i.e., Christian, and “false philosophy,” i.e., pagan, became inevitable. However, unlike what occurred in the West, neither Byzantine philosophers nor theologians completely rejected the Ancients; instead, they sought to use them for their purposes.

Perhaps the best illustration of this approach is Basil of Caesarea’s (330–379) treatise, “Address to Young Men on the Right Use of Greek Literature.” This moderation (economia) was not universal, though. In the early stages of Christianization, Emperor Julian (r. 360–363) not only attempted to restore ancient Greek culture but also the ancestral religion.

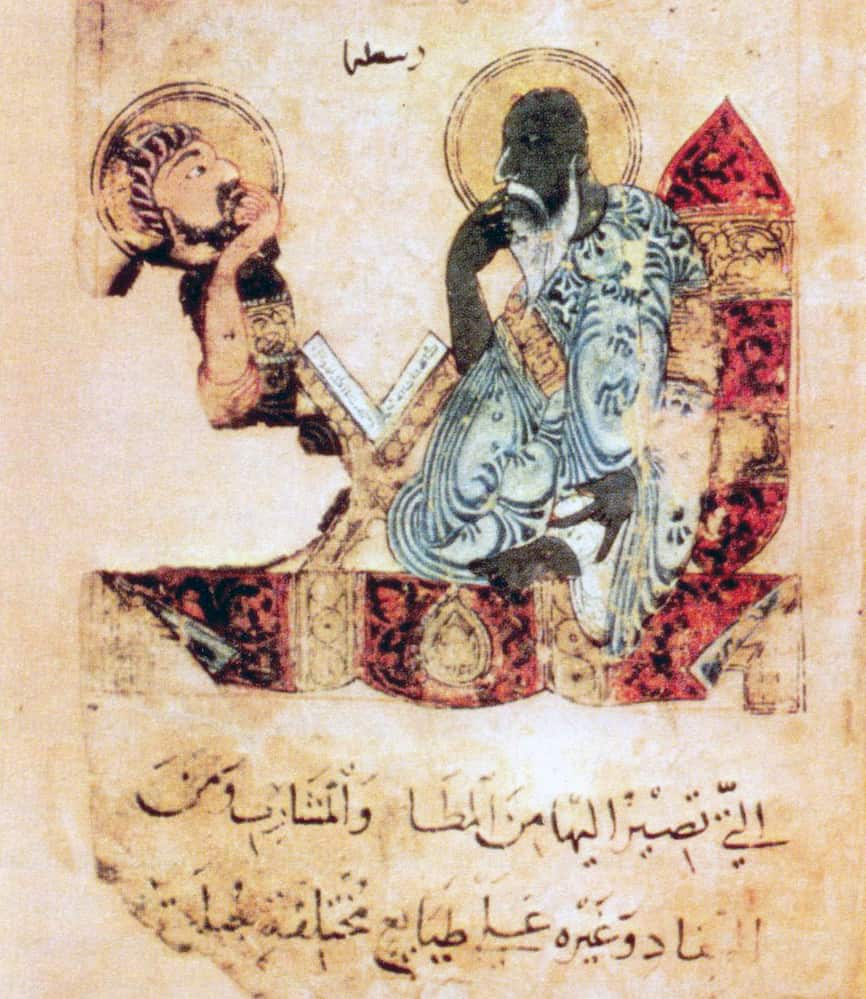

In the 5th century, the Prefect of Constantinople, Kyros Panopolites, was exiled from Constantinople for being too “Hellenic.” However, over time, a sort of osmosis occurred, so that by the early 8th century, John of Damascus (circa 676–749), a monk and theologian of Syriac origin but Greek language, could define philosophy as:

- The knowledge of existing things (onta),

- The knowledge of divine and human things,

- Preparation (melete) for death,

- Assimilation to God,

- The art (techne) of art, the science of sciences, and

- The love of wisdom.

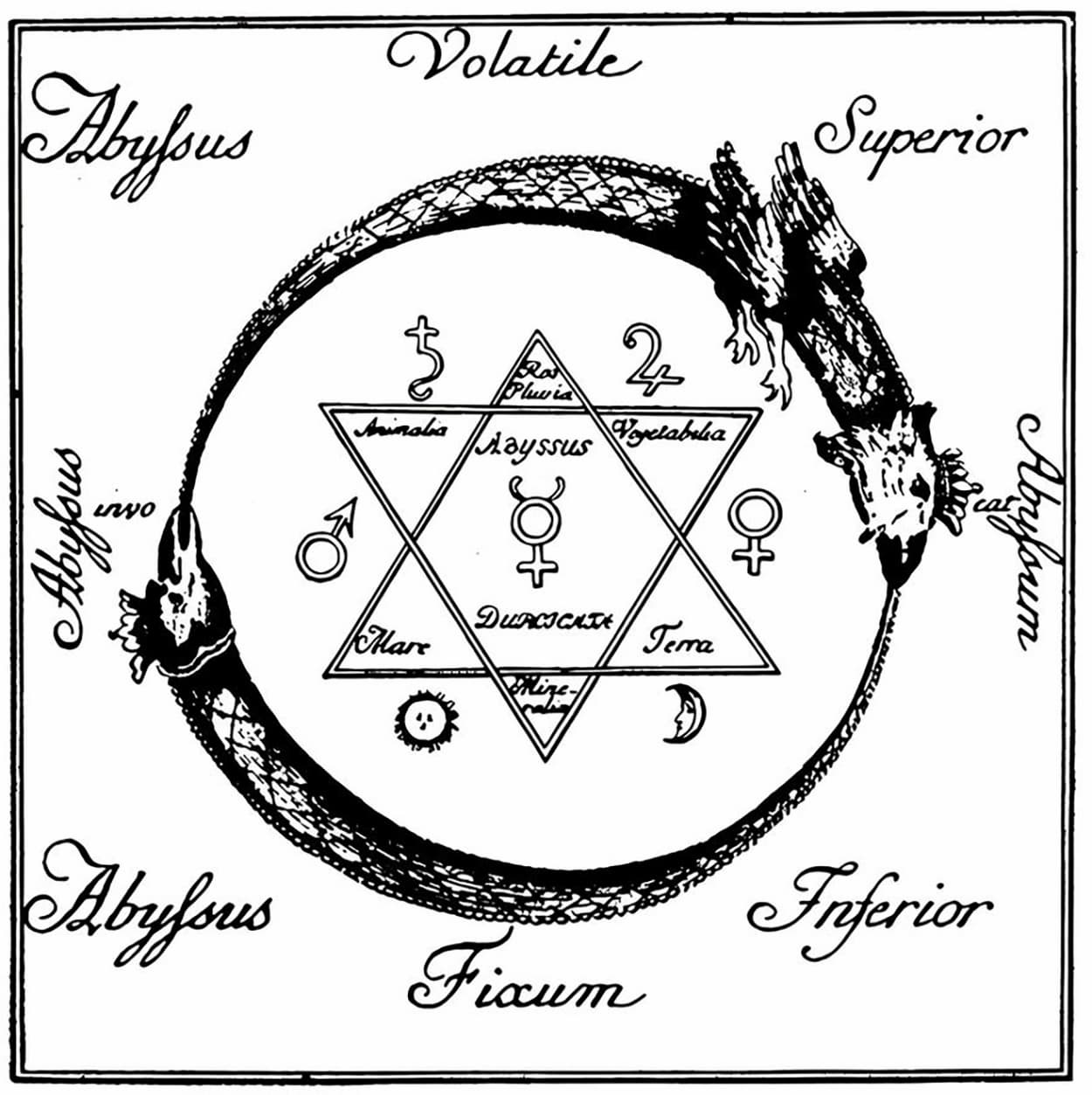

These definitions were drawn from Aristotle (1) and (5), the Stoics (2), and Plato (3) and (4); they were compiled by Neoplatonists from the school of Alexandria, such as Ammonius of Alexandria (a Christian mystic of the 3rd century), David the Invincible (an Armenian philosopher of the 5th and 6th centuries), and Elias of Alexandria (a philosopher from the School of Alexandria in the 6th century). John of Damascus summarized this thought in simple terms: “Philosophy is the love of wisdom, but true wisdom is God. Therefore, the love of God is true philosophy.”

Though somewhat arbitrary, the evolution of Byzantine philosophy can be divided into three periods, each beginning with the establishment or re-foundation of a major school: the end of the Amorian dynasty; the beginning of the Macedonian dynasty (842–959); the end of the Macedonian dynasty; the beginning of the Komnenos dynasty (1042-1143); and the beginning of the Palaeologian dynasty (1259–1341).

Equally arbitrarily, one could say that the first period was mainly dedicated to collecting and copying ancient authors, the second to commenting, paraphrasing, and critiquing them, while the third, marked by attempts to reconcile the Churches of Constantinople and Rome, would see a certain distancing in most philosophers allowing for the critique of ancient authors when they deviate from the official dogma, or, on the contrary, in some, the adoption of the Ancients at the expense of the Church’s doctrine.

History

The Precursors

The foundations of Byzantine philosophy can be found in Proclus, a Neoplatonist philosopher born in Constantinople in 412 into a wealthy family, which allowed him to study philosophy in Alexandria and then in Athens under Plutarch the Younger, the founder of the Neoplatonic school in that city. He would become the third director of the same school in 438 and undertake the most extensive philosophical synthesis of the very end of ancient Greek antiquity. With his disciple Ammonius, who founded his own school in Alexandria, they set the philosophical curriculum and made significant contributions, including the theory of structure and reality.

First Period: 843–959

Emerging from the iconoclastic crisis (726–843), as intellectual life returned to normal, foreshadowing the Macedonian Renaissance, Emperor Michael III (r. 842–867) handed over the reins of power to his uncle, Caesar Bardas, for ten years. A competent intellectual himself, Caesar Bardas decided between 855 and 866 to create an educational institution housed in the Magnaura Palace, entrusting its direction to Leo the Philosopher, also known as Leo the Mathematician.

Endowed with a great thirst for knowledge, Leo had initiated himself into all known sciences in his youth, including “philosophy and its sisters, namely arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy, and even music (i.e., the disciplines of the quadrivium).” He then opened his school in Constantinople, located in a private house, where he taught all intellectual disciplines to the sons of wealthy families destined for careers in the civil service.

His reputation as a scholar reached the ears of Caliph al-Mamun in Baghdad, who requested Emperor Theophilus to allow Leo to come to his court. Out of patriotism or caution, Leo declined the proposal and was appointed metropolitan of Thessaloniki around 840. Deposed in 843 for being an iconoclast along with John the Grammarian during the restoration of the cult of images, he was chosen by Caesar Bardas to lead his educational institution.

Little is known about this institution, which was supposed to give a new impetus to the study of ancient authors, except that Leo was to teach Aristotelian philosophy with the help of three colleagues whose names and functions are known: Theodore (or Serge), specialized in geometry; Theodegios, in arithmetic and astronomy; and Kometas, in grammar.

With Leo, the figure of a personality more concerned with philosophy and science than with literature emerges, as evidenced by his library: Plato for philosophy, a treatise on mechanics by Kyrinos and Markellos for mathematics, and volumes by Theon, Paul of Alexandria, and Ptolemy for astronomy, inseparable from astrology at that time.

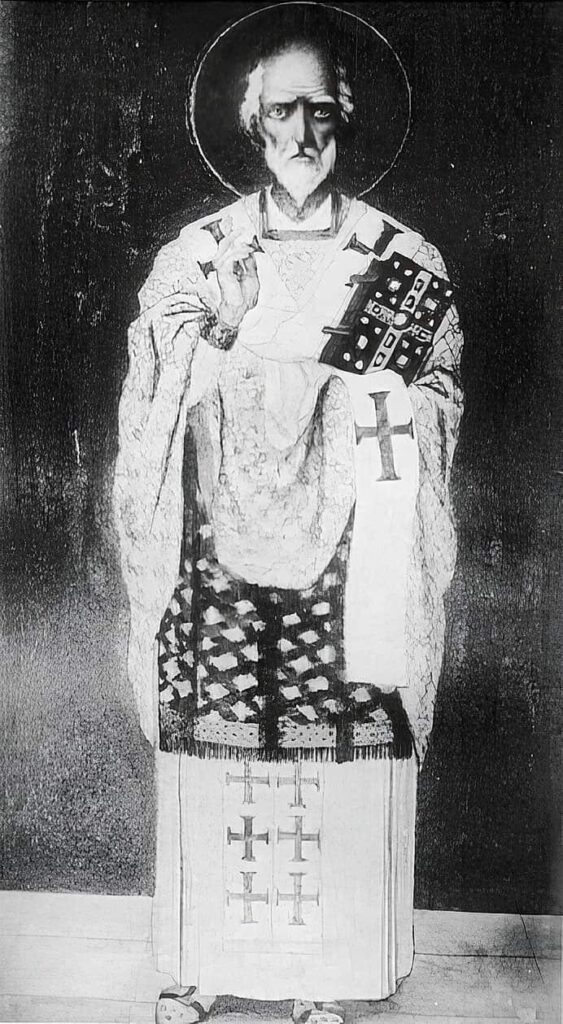

The second prominent figure of this generation was the Patriarch of Constantinople, Photios I, one of the most significant figures in the classical studies of Byzantine history. Possessing encyclopedic knowledge and likely self-taught, he began his career as a teacher before being appointed protasekretis, meaning chief of the imperial chancellery, around 850. This was the position he held when he was appointed patriarch in 858, although he was a layperson. He received all the ecclesiastical orders in six days, contrary to canonical law, leading to his disapproval by Pope Nicholas I.

The dispute between the churches of Constantinople and Rome escalated after the assassination of Caesar Bardas by Basil the Macedonian (r. 867-886). In the summer of 867, Photios convened a synod that declared the papacy and the Latin Church heretical. However, the same year, Basil had Michael III assassinated, dismissed Photios, and replaced him with Ignatius, who reclaimed his throne.

Exiled to the Stenos Monastery, Photios eventually reconciled with the emperor, who appointed him as the tutor to his heir, the future Leo VI (r. 886–912), whose relationship with his father was strained. As soon as Leo took power, he hastened to rid himself of Photios, whose career was shattered. Removed from his positions, Photios was sent into exile where he passed away.

His thoughts are evident in three main works: the Lexicon, an early work in which he explains the meanings of words found in the speeches and prose of antiquity, as well as the vocabulary of Christian authors requiring explanation; the Bibliotheca or Myriobiblos, an enormous work comprising 280 chapters corresponding to 1600 pages in modern editions, written for his brother Tarasios, summarizing the ancient Greek literature he read during his brother’s embassy; and the letters, some of which were included in the Amphilochia, addressed to Amphilohios, Metropolitan of Kyzikos, dealing with various theological and secular questions. In addition to comments on Aristotle’s Categories, they include discussions on the admiration expressed by Emperor Julian for Plato.

One of Photios’ disciples was the Archbishop of Caesarea, Arethas (c. 850–932 or 944), who commented on Aristotle’s Categories and Porphyry’s Isagoge. He is particularly known for collecting and copying numerous texts from both classical antiquity and Christian authors of the patristic period, including the corpus of Plato.

Without being a philosopher himself, Constantine VII (r. 913–959) would use the state’s resources to stimulate the initiatives of scholars, particularly through the copying and compilation of ancient works from antiquity. This period witnesses the waning of the philosophical revival and its transformation into a vast encyclopedic memory, with the most comprehensive illustration being the Suda. The Suda serves as both a dictionary presenting definitions of rare words in ancient Greek and complex grammatical forms and an encyclopedia commenting on individuals, places, or institutions.

Second Period: 1042–1143

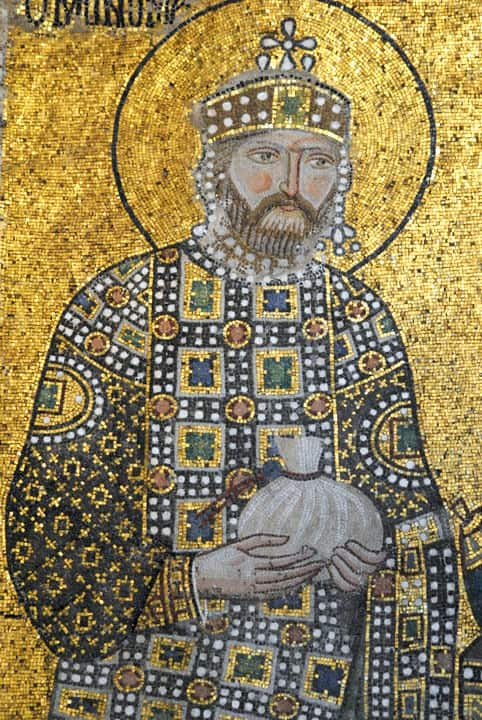

The second period begins with the ascent to power of Constantine IX Monomachos (r. 1042–1055), a senator who became emperor after marrying Empress Zoe (r. 1028–1050). Surrounded by intellectuals such as John Mauropous, Constantine Leichoudes, and John Xiphilinus, his reign would embody what is described as the “government of philosophers.” Like the first period, this second period starts with the establishment of a new school, this one dedicated to law.

Constantine VII had wanted to breathe new life into the school of Caesar Bardas. To achieve this, he appointed the protospatharios Constantin, then Mystikos (an important office in the civil service with an unknown exact function), as in charge of philosophy, the Metropolitan of Nicaea Alexander in charge of rhetoric, the patrician Nicephorus of geometry, and the asecretary Gregory of astronomy.

One essential discipline was missing, especially in an empire that was increasingly centralizing and bureaucratizing—the discipline of law, which had been taught in private schools until then. In 1047, Constantine IX established a new school, placing it under the nomophylax or “guardian of the laws,” and also housing it in the restored Magnaura Palace.

However, among the sciences taught, philosophy retained its privileged position, as attested by the judge and historian Michael Attaleiates: “[Constantine Monomachos] invigorated a school of jurists and appointed a nomophylax. But he also took care of the teaching of high philosophy and appointed a Proedros (Byzantine court) of philosophers, a man who surpassed us all in his knowledge.”

This man was Michael Psellos (1018–1078). A great scholar, he was also a prolific writer, covering diverse subjects such as etymology, medicine, tactics, law, and more. During his studies, he befriended individuals who would later hold key positions in the empire: the future Michael VII Doukas, John Mauropous, Constantine Leichoudes, the future “prime minister,” and John Xiphilinus, the future Patriarch of Constantinople.

However, he had to abandon his studies due to his family’s modest income and take a position as a judge in Philadelphie, Asia Minor. Upon his return to Constantinople, he resumed his studies and taught philosophy at Saint Peter’s School (secondary education). Then, under Constantine IX, he joined the imperial chancellery and became a minister in all the governments from Constantine IX to Michael VII. Disgraced, he died in relative obscurity.

His philosophical thoughts are encapsulated in his Chronographia, narrating events from 976 to 1078, and in about 500 letters he wrote in response to questions from correspondents or students since he continued teaching even after becoming a minister. Although he pays great attention to Aristotle’s work, his preferences undoubtedly lean toward Plato and the Neoplatonists, and he is recognized as a key figure in transmitting the Platonic heritage through the Middle Ages.

His works show that he read and assimilated Plotinus, Porphyry, Iamblichus, and especially Proclus, whom he considers an authority among the ancients. He finds, among other things, a metaphysical system in Proclus that can be adapted to Christianity. However, his theories, for example, those contained in the Chaldean Oracles, were often seen as contrary to Orthodox theology, and he had to make a public confession of faith in his defense.

His successor as the “consul of philosophers” would be John Italus (born around 1020; died after 1080). Born around 1020, he settled in Constantinople around 1050, where he attended the classes of Michael Psellos. A specialist in Plato, Aristotle, Porphyry, and Iamblichus, he began a teaching career at the Theotokos Euergetis (or Pege) Monastery. His reputation grew during the reign of Michael VII, and he was appointed to succeed his former master as the “consul of philosophers.”

After a stay in Italy as an ambassador to the Normans, he returned to Constantinople, but in 1076–1077, a synod condemned his theories for allegedly exceeding the limits imposed on natural reason and the proper relationship between philosophy and theology. When Alexis I ascended the throne, he undertook to combat heresy at all levels, and against the patriarch’s advice, Italus was once again condemned following an autocratic trial. Barred from teaching, he was exiled.

In fact, Italus’ positions were not significantly different from those of Psellos; what seemed unacceptable to the political and religious authorities of the time was his rationalistic approach to doctrines that the Orthodox Church considered beyond human understanding and within the sole purview of the Church to determine. In other words, Italus followed the Ancients’ conception that theology was an integral part of philosophy and not an autonomous discipline.

The second successor to Psellos, likely appointed after the deposition of John Italus, was probably Theodore of Smyrna (mid-11th century, after 1112). Little is known about this high-ranking official in the Byzantine administration, except that he served as a judge, then as prōtoproedros, and finally as kouropalates. Only fragments of his literary activity, which must have been significant, have survived, including commentaries on Aristotle, a treatise against the Latin Church on azymes and the procession of the Holy Spirit.

Erudite and historian Anna Komnene contributed to the advancement of philosophy by sponsoring a series of commentaries on certain works of Aristotle that were previously little known. Two of the authors who contributed to this work were Eustratius of Nicaea and Michael of Ephesus. Eustratius of Nicaea was a disciple of John Italus; he narrowly escaped Italus’ condemnation by subscribing to it. He retained his position as director of the School of Saint Theodore.

Later, he gained the favor of Emperor Alexios Komnenos by defending the sovereign’s viewpoint on icons against accusations of iconoclasm made by Metropolitan Leo of Chalcedon.

Eustratius was appointed Metropolitan of Nicaea. When the emperor sought to convert the Armenian minority (Monophysite) in Bulgaria, he composed a “dialectical discourse on the two natures of Christ” and the outline of two treatises on the same subject. However, similar to Psellos and Italus, the imprudence of his “dialectician” language scandalized the conservative-minded. A lengthy trial ensued in which the emperor and Patriarch John IX Agapetos attempted to plead in his favor, but the trial ended in his condemnation. Eustratius would die a few years later.

In the surviving commentaries on Aristotle, Eustratius evidently follows the ancient Neoplatonists, although on some subjects, such as the knowledge of first principles, he supports theses closer to Christian doctrine. Unlike Plato and Aristotle, he does not believe that the human soul reappropriates the knowledge it had originally, nor does he hold that it possesses only virtual knowledge that gradually materializes. According to him, the human soul, as created by God, is already perfect, meaning it has full knowledge of first principles and immediately evident concepts. However, humans progressively lose this knowledge and understanding due to the instincts of their bodies.

We know very little about the life of Michael of Ephesus, except that he taught philosophy at the University of Constantinople and, along with Eustratius of Nicaea, was part of the circle set up by Anna Komnene to continue the study of the lesser-known works of Aristotle. However, his reputation as a commentator on Aristotle was well-established, and his method of exposition and interpretation has been compared to that of Alexander of Aphrodisias, a commentator on Aristotle in the 2nd century. His commentaries on several works of Aristotle, especially Metaphysics, Parts of Animals, and Generation of Animals, align with the Neoplatonists and the tradition of Stephen of Alexandria.

In the following century, Theodore Prodromos (circa 1100–circa 1170) continued the tradition of detailed commentaries on the works of Aristotle, notably on the Analytics, where the determining influence of Eustratius of Nicaea is palpable. A prolific author, he mainly worked in the fields of poetry and rhetoric, but he also contributed philosophically with another commentary on Aristotle’s Analytics, heavily influenced by Eustratius of Nicaea.

Not all scholars of the time were fervent admirers of Aristotle, Plato, and the Neoplatonists. This was the case, among others, with Nicholas of Methone, bishop of that city around 1150, who, in the name of Orthodox Christianity, wrote a detailed refutation of Proclus’ Elements of Theology. According to him and conservative Orthodox theologians, Neoplatonic influences on Christian doctrine could lead believers away from true faith. Thus, he systematically opposed Proclus’ propositions, attempting to demonstrate that the first principle of the universe is “one,” considering this proposition contrary to the doctrine of the Trinity.

The sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 proved catastrophic for educational institutions. Many intellectuals had to emigrate, some to Italy, others to the Empire of Nicaea, where Theodore II (r. 1254–1258) himself was a scholar, authoring two works on natural philosophy, the Kosmikē dēlōsis (Cosmic Exposition) and the Peri phusikēs koinōnias (On Physical Community). In these works, he relied on simple mathematical schemes to understand the theory of elements and cosmology.

Third Period: 1259–1341

After the reconquest of the city by Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261, official education was restored by the Grand Logothete George Akropolites, who established a modest school where courses focused on the philosophy of Aristotle, Euclid’s geometry, and Nicomachus of Gerasa’s arithmetic. In 1266, Patriarch Germanos III (Patriarch 1223–1240) restored the patriarchal school.

However, it was under Andronikos II (r. 1282–1328) that a new imperial school, the Scholeion basilikon, was founded under the jurisdiction of the Grand Logothete Theodore Metochites. During this period, marked by attempts to reunify the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches, theological debate profoundly influenced philosophical discussions, with the question of the procession of the Holy Spirit (the Filioque controversy) remaining at the heart of this division.

The central figure at the beginning of the Palaiologan restoration was Nikephoros Blemmydes. Born in 1197, he had to flee Constantinople with his family and seek refuge in Bithynia, where he studied medicine, physics, philosophy, theology, mathematics, logic, and rhetoric. After founding a school in Smyrna at the emperor’s request and then leading the imperial school of Nicaea from 1238 to 1248, he had to retire due to harassment from the city’s clergy.

He then became a monk and, in 1241, founded a monastery in Emathia, near Ephesus, whose school focused on training future monks and novices. In a preliminary note to his treatise on logic, apparently written in 1237 at the request of Emperor John III Vatatzes (r. 1222–1254), he emphasizes the utility of logic in theology. His services were often required to defend the Orthodox position in the Greco-Latin debates of 1234 and 1250, including writing treatises on the procession of the Holy Spirit and being a defender of the ancient patristic formula that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father “through” the Son.

More well-known as a historian, George Pachymeres (1242–circa 1310) taught at the patriarchal school and wrote an extensive treatise titled “Philosophia,” paraphrasing Aristotle and dealing not only with logic and natural philosophy but also with metaphysics and ethics, in addition to the last known Byzantine commentary on Plato, a continuation of the Parmenides, an incomplete commentary by Proclus in which he applies a “logical” (i.e., non-metaphysical) method of interpretation. He was also a great collector, translator, and editor of the manuscripts of philosophers.

The reign of Andronikos II also saw the emergence of an original philosopher, Nikephoros Choumnos (circa 1250 or 1255–1327), who wrote on natural philosophy without reference to ancient authors. After serving as prime minister of the emperor for nearly eleven years, he was ousted by his great intellectual rival, Theodore Metochites. He then lived for some time on his estates before being appointed governor of Thessalonica, the country’s second-largest city, where he remained until around 1326, engaging in long polemics with his political and intellectual rival.

Choumnos’ approach is unique in that he applies philosophical logic, that is, inference to universally accepted principles and definitions, to accepted theological ideas. While he proves to be an ardent defender of Aristotle, he does not embrace the entirety of his system. Instead, he prefers to provide a rational and philosophical justification for Christian theological doctrines. His attacks on Platonic theories of substance and form or his refutation of Plotinus’ theories on the soul aim to demonstrate the validity of Christian teachings.

A rival to Choumnos, Theodore Metochites (1270–1332), succeeded in replacing the former as the Grand Logothete of Andronikos II. During this period, he established a public education service called the Mouseion in memory of the institution in Alexandria and proved to be a great patron of the arts and sciences. His political career was interrupted in 1328 when the emperor was dethroned by his grandson. After being exiled for a few months, he was able to return to Constantinople, where he retired to the Chora monastery, which he had restored.

A statesman by day, Metochites, deeply immersed in the culture and language of ancient Greece, dedicated his free time to intellectual pursuits. A versatile writer, he admired Aristotle and especially Plato, but like Choumnos, he did not accept all their opinions. His Sēmeiōseis gnōmikai (Miscellanies) is a collection of one hundred essays on various subjects (politics, history, moral philosophy, aesthetics, classical Greek literature), in which he does not hesitate to criticize Aristotle’s obscurity and Plato’s use of dialogue. Many of his essays are reflections on the transience of human life, while others are paraphrases or commentaries on Aristotle’s philosophy as contained in his various treatises.

Becoming an orphan at a very young age, Nikephoros Gregoras (circa 1295–1360) began his studies under the guidance of his uncle John, the Metropolitan of Heraclea. Around 1315, he arrived in Constantinople, where he studied logic and rhetoric under the future Patriarch John XIII Glykys and philosophy and astronomy under Theodore Metochites, who introduced him to Aristotle’s philosophy. Gregoras was to become the Metochites’ intellectual successor, establishing himself at the Chora monastery, where he directed a school.

Having achieved an enviable reputation within the circle of Byzantine scholars and humanists, Gregoras became involved in the conflicts between Andronikos II and his grandson, Andronikos III, and later in those between John V Palaiologos (r. 1341 – 1376, 1379 – 1390, September 1390 – February 1391) and the future John VI Kantakouzenos (r. 1347 – 1354). However, what marked his philosophical activity the most was the long struggle he waged against the Calabrian Barlaam. Initially, in 1330, during a public debate initiated by Barlaam, and later from 1340 when Barlaam ignited the Hesychast controversy in Thessaloniki, which would divide the empire for ten years. Primarily a rhetorician, it was in this ongoing dispute until the end of his life that he touched on various philosophical subjects, including his criticism of Aristotle in the dialogue Florentius, evidently based on his first encounter with Barlaam.

Gregoras also came into conflict with another theologian and philosopher who was also involved in the conflict between John V Palaiologos and John VI Kantakouzenos: Gregory Palamas (1296–1359). Of aristocratic origin, Palamas chose the monastic life on Mount Athos over imperial administration at a young age. Ordained as a priest in 1326, he began correspondence with Barlaam in 1336, leading to the development and structuring of his doctrine, Palamism.

Soon, this religious dispute extended to civil society, with John VI, many important clergymen, and the monks of Mount Athos, whose spirituality was based on Hesychasm, siding with Palamas. The politico-religious crisis was resolved in 1347 when a council deposed Patriarch John Kalekas and confirmed the orthodoxy of Palamas’ theses. John Kantakouzenos then became co-emperor with young John V; Isidore became the patriarch of Constantinople; and Palamas became the metropolitan of Thessaloniki. While undertaking various diplomatic missions for the emperor, Palamas continued his struggle against Gregoras, writing his Four Treatises against Gregoras between 1356 and 1358.

According to Palamas, while the substance (ousia) of God remains unknown to man, he can directly experience it through divine activities (energeiai) visible to him. In his “150 chapters,” Palamas denounces what he considers the erroneous views of ancient philosophers, both followers of Aristotle and Plato, devoting the first twenty-nine chapters to defining natural philosophy, placing facts concerning the world as a whole (as opposed to specific facts like astronomical phenomena) in the same epistemological category as facts concerning God and humans.

During this third period, many philosophers tended to identify themselves as either “Aristotelians” or “Platonists,” contrary to the attempts of previous eras that primarily aimed to reconcile the two tendencies. Already present in Gregoras and Metochites, anti-Aristotelian sentiments became more evident in Georgios Gemistos Plethon (circa 1360–1452).

Born in Constantinople between 1355 and 1360, Georgios Gemistos initially studied within the Platonic school of Constantinople. Later, in the cosmopolitan environment of Adrianople, where Christians, Jews, and Muslims taught, he returned to teach in Constantinople. However, his lectures on Plato caused a scandal and nearly led to his arrest for heresy. Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1391–1425), his friend and admirer, chose to exile him to Mistra, which had become a significant intellectual center in the Despotate of the Morea (former country).

As a member of the Byzantine delegation, serving as a lay delegate at the Council of Florence (1437–1439) when he was already in his eighties, he delivered numerous lectures in the city, reviving Platonic thought in Western Europe. It was during this time that he began using the pseudonym Plethon. Upon his return to Mistra, he was appointed to the Senate and became a magistrate of the city. He spent his final years teaching, writing, and continuing the feud with Gennadius II Scholarius, Patriarch of Constantinople and an advocate of Aristotle.

Following his discussions with Florentine intellectuals, he wrote his pamphlet “On the Differences between Aristotle and Plato,” seeking to demonstrate Plato’s superiority to Aristotle. Despite Aristotle’s greater admiration for Western Europe, where the ancient Greek authors had been rediscovered, in part due to exiles from Constantinople fleeing the city after the Fourth Crusade and the subsequent civil wars, Plethon emphasized the weaknesses in Aristotle’s theories. This led to an immediate response from Patriarch Gennadius II Scholarius, titled “In Defense of Aristotle.” Plethon then published a reply, arguing that Plato’s concept of God was closer to the Christian doctrine than Aristotle’s. The dispute lasted for thirty years, concluding with Cardinal Bessarion’s publication of “Against the Slanderers of Plato” (circa 1469).

Key Themes of Byzantine Philosophy

Throughout its evolution, Byzantine philosophy focused on fundamental truths concerning man and the world in which he lives. In this sense, it remained “the science of the external,” while theology was “the science of the internal.” Both were complementary, whereas in the West, philosophy remained either the “servant” or the “background” of theology.

In the West, classical humanities disappeared with the barbarian invasions, replaced by a profound distrust of “pagan ideas,” as evidenced by Tertullian’s question, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” On the contrary, the Greek Fathers of the Church taught that God could be discovered through Greek philosophers. “All who live by applying the methods of reason (logos) are Christians, even if they are classified among atheists […] because each, through the presence of the divine logos within him, has spoken well […] and what every man has said, when he was well-guided, belongs to us Christians.”

The Greek Church thus concluded that the study of ancient wisdom was both useful and desirable, provided that Christians rejected erroneous ideas, retaining only what was true and good. This perspective is expressed in the treatise of Basil of Caesarea, already mentioned, “Exhortation to Young People on the Best Way to Profit from the Writings of Pagan Authors.” The Greek Fathers of the Church did not seek to borrow the essence or content of ancient thought but aimed to adopt the method, technical means, terminology, logical structures, and grammatical elements of the Greek language to construct Christian theology and philosophy.

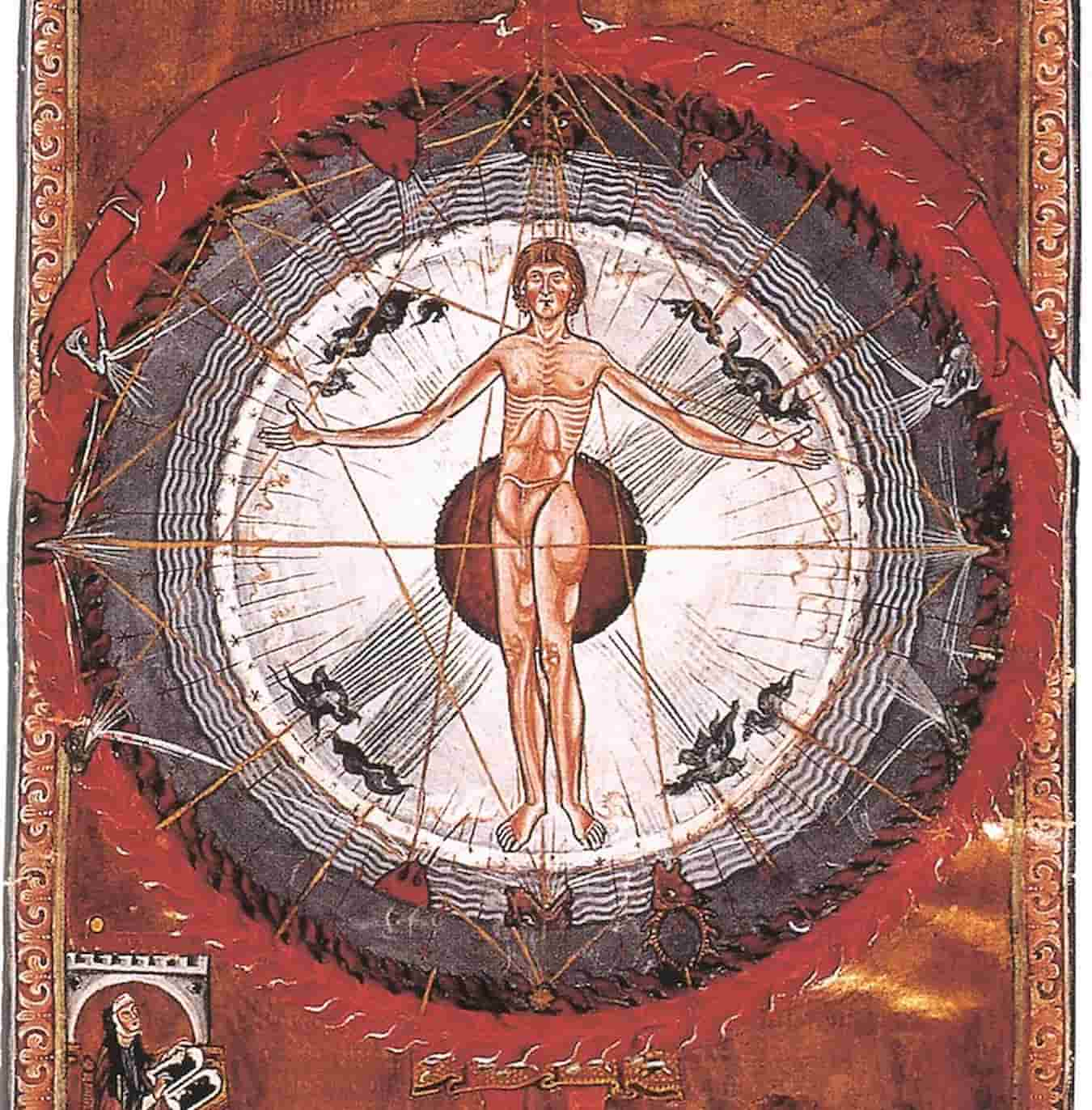

For the Byzantines, the ultimate destiny of humanity was to achieve “theosis,” meaning union or integration with divinity (without being absorbed into it, as in Hindu pantheism). “Theosis” became synonymous with “salvation” or “eternal life in the presence of God,” while damnation was the absence of God in human life. The attainment of “theosis” was through religious experience.

This concept was not far from ancient Greek thought, where theosis was not to be achieved through theology but through philosophy, study (paideia), and the development of intelligence. This idea was defined in the 4th century by the pagan rhetorician and philosopher Themistius (c. 317–c. 388): “Philosophy is nothing other than assimilation to god as far as this is possible for a human.”

More theoretically, the main themes of Byzantine philosophy included:

- The substance or essence of God in its three hypostases (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) and the two natures of the Son.

- The creation of the Universe by God and its limits in time.

- The continuous process of creation and the intention it reveals.

- The world is perceived as a realization in time and space, with its hypostasis in the divine mind (nous).

Other Philosophical Traditions

Byzantine philosophy did not develop in isolation; it was one of the four major traditions of the Middle Ages, with the other three being Arabic philosophy, Jewish philosophy, and Latin philosophy. Arabic philosophy, expressed in Arabic and sometimes in Persian, was prominent from the 9th century until the death of Ibn Rushd (Averroes) in 1198.

After that, religious intolerance hindered the independent development of philosophy. Starting shortly after Arabic philosophy and deeply connected to it, Jewish philosophy developed in colonies established in both the Arab world and Christian Europe, dwindling by the 15th century. In Latin Western Europe, an original philosophical movement emerged at the court of Charlemagne without a clearly defined end except for the Renaissance, which had varying starting points in different countries.

Taken as a whole, what stands out more than their differences is what unites these traditions. All four drew from ancient Greek philosophy, particularly as taught by Neoplatonic schools, as their common heritage. Secondly, they influenced each other throughout their existence: medieval Jewish philosophers were deeply influenced by Arabic philosophers, and the translation of these philosophers transformed the philosophical course of Latin Western Europe from the 12th century onwards.

Only Byzantine philosophy, relying on the ancient heritage, was less open to other currents, although there were various translations from Latin towards the end of the Middle Ages. Finally, these four philosophies belonged to cultures dominated by a revealed monotheistic religion. Although the relationships between these religious doctrines and philosophical speculations varied from one tradition to another, or even from one era to another within each, the questions they posed about the meaning of man and his relationship to divinity were substantially the same, and theological questions were to profoundly influence the development of philosophical thought.

The Main Byzantine Philosophers Include:

- Proclus, a Neoplatonist, born in Constantinople in 412 and died in Athens in 485. He is considered the precursor of Byzantine philosophy.

- Stephen of Alexandria, born around 580 and died around 642.

- John Damascene, born in Damascus around 676, died at the Mar Saba Monastery (Palestine) in 749.

- Leo the Philosopher or Leo the Mathematician, born between 790 and 800, died in Constantinople after 869.

- Arethas of Caesarea, born around 860 in Patras, still alive in 932.

- Suda, a Greek encyclopedia from the late 10th century whose author or authors are anonymous.

- Photius I of Constantinople, born around 820 in Constantinople, died in exile in 891 or 897.

- Michael Psellos, born in Constantinople in 1018, died in Constantinople shortly after the death of Michael VII (1078).

- John Italus, born in southern Italy around 1020, died after 1082.

- Eustratius of Nicaea, born around 1050, died around 1120 or 1130.

- Michael of Ephesus, mid-11th century.

- Theodore Smyrnaios (Theodore of Smyrna), first mentioned in 1082, seemingly died after 1112.

- Nicholas of Methone, born in the early 12th century, died in 1160 or 1166.

- Nikephoros Blemmydes, born in Constantinople in 1197, died in Constantinople around 1269.

- Nikephoros Choumnos, born in Thessaloniki around 1250 or 1255, died in Constantinople in 1327.

- Theodore Metochites, born in 1270 in Constantinople, died in Constantinople in 1332.

- Joseph the Philosopher, born in Ithaca around 1280, died in a monastery near Thessaloniki around 1330.

- Gregory II of Cyprus, born in Lapithos (Cyprus) in 1241, died in Constantinople in 1290.

- Nikephoros Gregoras, born around 1295 in Heraclea Pontica, died in Constantinople in 1360.

- Gregory Palamas, born in Constantinople in 1296, died in Thessaloniki in 1359.

- Plethon Gemistos, born in Constantinople between 1355 and 1360, died in Mistra in 1452.

- Manuel Chrysoloras, born in Constantinople around 1355, died in Constance in 1415.

- John Argyropoulos, born around 1395 in Constantinople, died in Rome in 1487.

- Theodore Gaza, born in Thessaloniki around 1400, died in Rome around 1478.

- Gennadius II Scholarius, born in Constantinople around 1400, died in Macedonia around 1473.

- George Amiroutzes, born in Trebizond in the early 15th century, died around 1470.

- Michael Apostolius, born in Constantinople around 1422 and died on June 18, 1478.

- Andronikos Callistus, born in Constantinople in the early 15th century, died in London after 1476.