Popol Vuh (K’iche’: Popol Wu’uj) is a historical-mythological text of the K’iche’ (in the old spelling: Quiché), a Maya people from Guatemala, which was transcribed into European script shortly after the Spanish conquest (mid-16th century). The document was presumably composed by members of the K’iche’ nobility to legitimize their own position in the emerging colonial society.

The first part of the Popul Vuh recounts the creation of the earth and humans. The creation of humans did not succeed at first: the first attempt resulted in the creation of animals; the first human made of clay was too weak; the second made of wood lacked intelligence and walked on all fours; only the human made of corn was perfect. He was too perfect, and his sight had to be clouded so that his wisdom was limited. He was not meant to be like the gods. During his sleep, his wife was created. Four pairs of humans, created from corn, were the ancestors of the K’iche’ Maya.

Before their history is further recounted, the myths surrounding the divine twins Hunahpu and Ixbalanqué are discussed: their victory over the proud Seven Macaw and his sons, their birth from the spit of Hun Hunahpu (One Hunter) and the disobedient maiden Ixquic. She desired to taste the forbidden fruits of the calabash tree. This tree bloomed after Hun Hunahpu’s body was placed within it. He had been defeated by the Lords of the Underworld, Xibalba. Hun Hunahpu already had two sons, who were turned into monkeys by the divine twins and driven into the forests. The twins returned to Xibalba and defeated the Lords of Death. Afterward, the brothers ascended as the sun and moon.

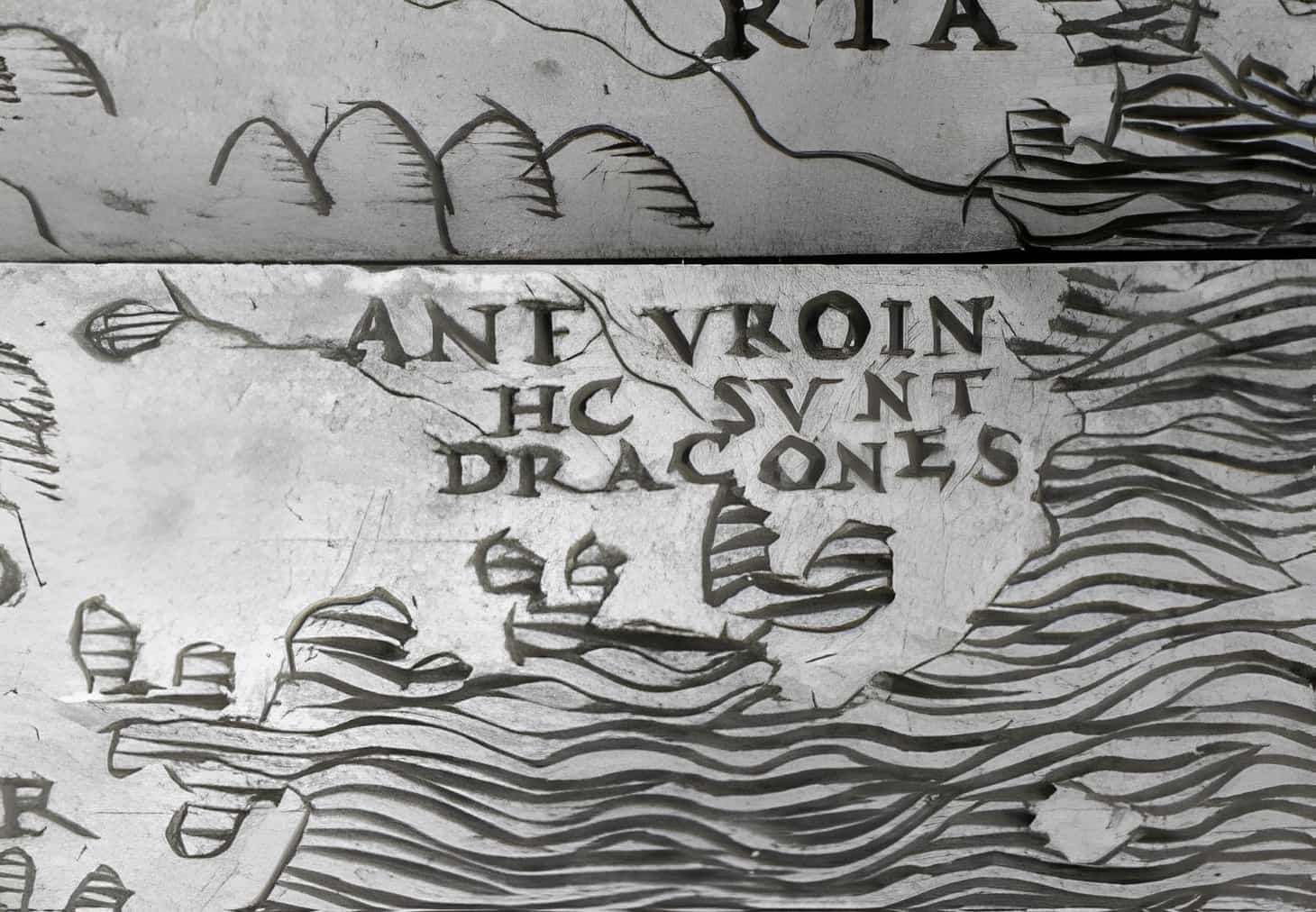

The migrations of the Maya tribes, described in the second part, led eastward from Tula (Tollan) to Santa Cruz del Quiché, while the book repeatedly states that the Maya originally came from the east, migrated to Tula, and that even Tula lay in the east. A catastrophe must have occurred as the Maya left their homeland and traversed the darkness, dressed only in hides, in the cold, and without food. They had to wade through the sea and wait for dawn until the sun finally dried the earth’s surface.

Three sons of the maize ancestors traveled ‘to the other side of the sea’ in the direction ‘where the sun is made [the east]: from there came our fathers.’ They received from King Nacxit (Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl), ‘the lord of the sunrise,’ the signs of kingship and ‘the writing from Tula,’ in which their history was recorded, and returned home with it.

Manuscripts and Editions

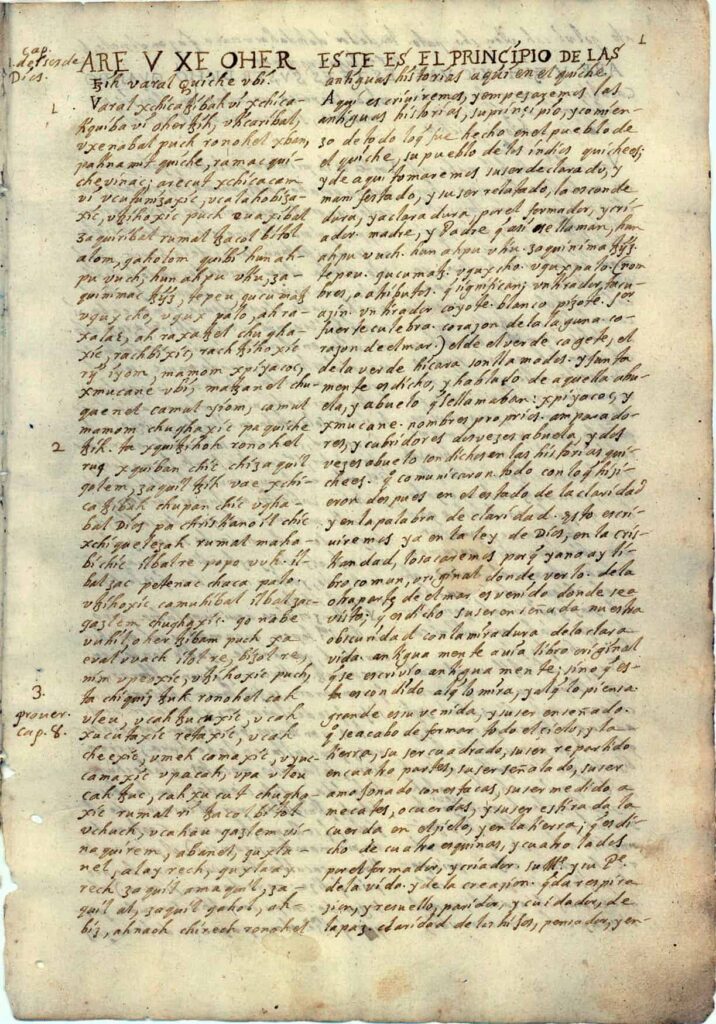

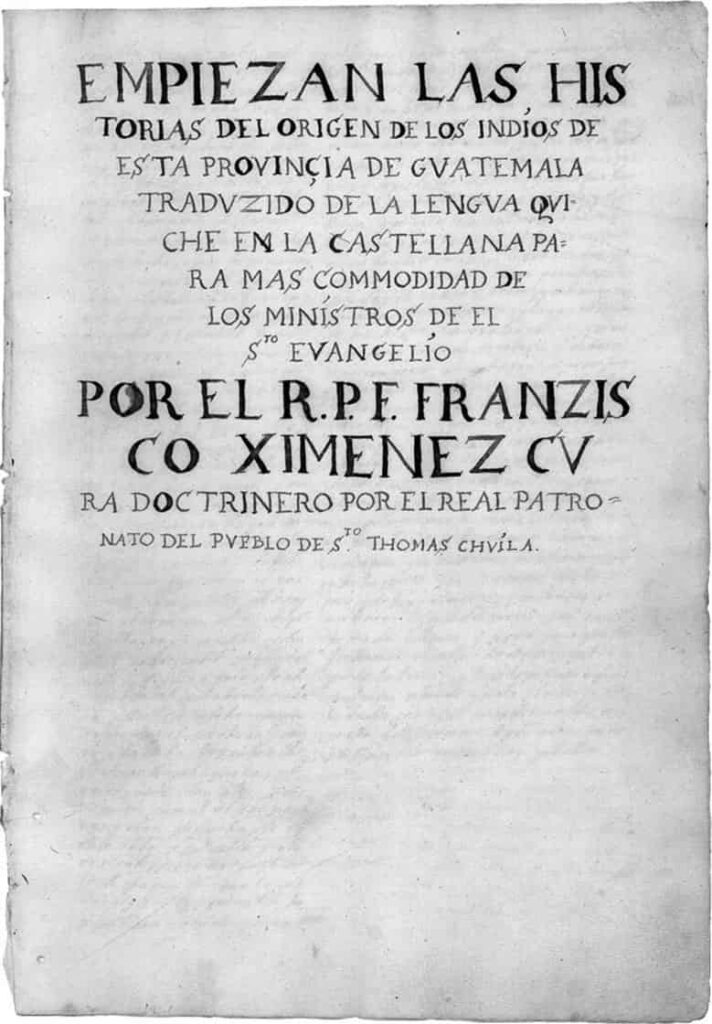

The original manuscript of the Popol Vuh has been lost: all editions are based on a copy from the early 18th century, the Chichicastenango manuscript (Chuilá in K’iche’). This 112-page copy was made by the parish priest of Chuilá, the Dominican Francisco Ximénez (1666-1729), and presents the Mayan text and the Spanish translation in two columns. The modern editorial history of the Popol Vuh begins in 1861 with the publication of the original and its French translation by Brasseur de Bourbourg; since then, numerous new, annotated translations have appeared as research into traditional Mayan culture has progressed (with Schultze Jena, Recinos, Edmonson, Tedlock, and Christenson being the most prominent).

Content

Popol Vuh literally means ‘Book (vuh) of the Mat (popol)’, to be understood as ‘Book of the Council Meeting’. It is essentially a history of the origin of the K’iche’ kingdom of Q’umarkaj that reaches back into the distant mythological past. The structure of the text somewhat resembles that of the Bible (from Genesis to Kings and Chronicles). However, although Christianization was already underway, its influence on the text itself is minimal.

First Part

Creation

The narrative begins with the creation of the earth and the first, yet unsuccessful attempts to create humans. Especially in this section are the oldest prayer texts known from the Maya.

‘Once there was the resting universe. Not a sigh. Not a sound. The world is motionless and silent. And the space of the heavens was empty.’ Thus begins the story of creation. ‘In the water, illuminated by light’ were ‘Tzakól, the creator; Bitól, the shaper; the victor Tepëu and the green-feathered snake Gucumátz; Alóm also; and Caholóm, the progenitors.’ And there was Huracán, ‘the Heart of the sky called Cabavil, he-who-sees-in-the-dark. (..) His first appearance is the lightning, Cakulhá. His second, the thunder, was Chipi Cakulhá. His third is the lightning bolt, Raxa Cakulhá. These three form the heart of the sky.’ Tepëu and Gucumátz came together and discussed the ‘creation of man.’ They created the earth. The earth was formed by ‘the heart of the sky’ and ‘the heart of the earth’, which ‘first impregnated her’. Then the animals were created, ‘our first works, our first beings,’ but the progenitors Tzakól and Bitól were dissatisfied because the animals could not speak, praise, or worship the gods. ‘Therefore, we shall create others who are willing.’

A new attempt was made to create man. ‘From clay they made the flesh of man, but ‘it was too soft, it was without motion and without strength (..) it had no understanding’. It could not walk or multiply and was destroyed. The progenitors decided: ‘Let us say to Ixpiyacóc [Grandfather Daykeeper], Ixmucané [Grandmother Duskkeeper], to Hunahpú-Vuch and Hunahpú-Utiú: Try it again.’

Ixpiyacóc ‘cast lots’ with tsité beans and ‘people of wood’ were created. ‘From tsité was the flesh of man made, but the flesh of the woman (..) from reeds. ‘The wooden people ‘had no soul, no understanding (..) they walked on all fours. (..) Those were the first people; numerous of them lived on the face of the earth. ‘They too were destroyed, beaten with sticks and stones, pots and pans, torn apart by dogs, drowned in a flood. ‘And it is said that their descendants are the monkeys that now live in the forests. In the monkeys, one can recognize those from whom the creator and shaper made the flesh of wood. That is why the monkey resembles man, as a reminder of a creation of humans, of humans who were nothing but wooden dolls.’

The Divine Twins

Next, the deeds of the sons of Ixquic, the Heroic Twins Hunahpu and Ixbalanqué, are described: their neutralizing of the proud Seven Macaw, a bird demon, and his two sons, Zipacná (the Strong) and Cabracán (the Shaker, Two-Legged). Zipacná had killed ‘400 youths,’ who had first attempted to bury Zipacná in a pit with an enormous log. Zipacná is slain by the heroic twins through trickery. They made a crab and placed it in the water at the foot of a mountain. When Zipacná dove for it, the mountain slid onto his chest. Cabracán was incapacitated by feeding him a bird covered in white lime, causing him to lose all his strength and be buried in chains.

Only after the deaths of Seven Macaw and his sons is it told how the heroic twins were born. The brothers Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunahpu (One Hunter and Seven Hunter) lost their lives in the Underworld in battle with One Death and Seven Death, and the body of Hun Hunahpu was hung in a calabash tree, which then began to bloom beautifully. Ixquic, the daughter of one of the Lords of Xibalba, the Underworld, desired to taste the calabashes, spoke with the head of Hun Hunahpu, and received his saliva on her hand. After that, she became pregnant and was driven away by the Lords of Xibalba. She went to the house of Ixmucané, the mother of Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunahpu. Ixmucané cared for the two sons of Hun Hunahpu’s previous wife. Ixquic must prove that she truly carries the sons of Hun Hunahpu. The heroic twins are born.

Then follows the banishment of One Monkey and One Artisan, two jealous older brothers, to the forests, and especially the avenging of the father through the subjugation of the underworld, an adventure in which the Mesoamerican ballgame plays a significant role. Hunahpu and Ixbalanqué transform into the sun and the moon, respectively.

Completion of Creation

Finally comes the ‘completion of creation’: ‘They must appear, those who sustain us and feed us, the radiant sons of light.’ The’stuff of life’ was found: ‘from Pan Paxil and Pan Cayalá [a wonderfully beautiful land full of pleasant things] came the yellow and white corn cobs.’ There were four animals that brought the yellow and white corn: the wildcat, the coyote, the parrot, and the raven. Ixmucané ground the corn cobs and made nine drinks, which gave ‘strength and abundance’, from which ‘the strength and the power of man’ were created. From corn dough, the four ancestors of the K’iché were created: the Forest Jaguar, the Night Jaguar, the Lord of the Night, and the Moon Jaguar. They were created and formed; they were not born of a woman. ‘Only by a miracle, by sorcery, were they created and formed by Tzakól, Bitól, Alóm, Caholóm, Tepëu, and Gucumátz. (..) A reason was given to them. They looked inward and also looked into the distance; they came so far that they saw everything, knew everything that exists in the world (..) Their wisdom was great. (..) And whatever is great or small in the sky or on the earth, we see it. (..) Soon they knew everything.’ But the creator and shaper were not satisfied and said, ‘Should they also be gods? (..) Should they eventually be like us, who created them and can see very far, know everything, and see everything?’ Then Huracán ‘cast a veil over their eyes. And they became clouded: they could only see what was nearby. Thus, the wisdom and all knowledge of the four people of the origin and the beginning were destroyed.’

Then the spouses were created; they appeared ‘during sleep’: Skywater was the wife of the Forest Jaguar, Springwater of the Night Jaguar, Hummingbirdwater of the Lord of the Night, and Parrotwater of the Moon Jaguar. ‘They begot the people, the small and the large tribes. And they were the origin of us, of the K’iché tribe. (..) There were more than four, but four were the progenitors of our K’iché tribe. Different were the names of all when they multiplied there in the east, and numerous were the names of the tribes: Tepëu [Tepëu-Yaqui], Olomán [Olmecs], Cohá, Quenéch, and Aháu. Thus the tribes called themselves when they multiplied there in the east. Also, the origin of the Tamúb tribe and of the Ilocáb tribe is known; they came together from the east. Balam-Quitzé, Forest Jaguar, was the grandfather and father of the nine great Cavéc families. The Night Jaguar, Balám-Acáb, was the grandfather and father of the nine great Nimhaib families. Mahucutáh [Lord of the Night] is the grandfather and father of the four great Ahau-Quiché families. There were three family groups, but they did not forget the names of their grandfather and father, not those who spread and multiplied in the east. Also, the Tamub and Ilocáb arrived [in Tula], and thirteen subtribes, the thirteen of Tecpán [Pocomanes and Pocomchis]. And the Rabinals, the Cakchiquels, those of Tzikinahá, and those of Zacahá and Lamák, Cumatz, Tulhalhá, Uchabahá, those of Chumilahá, those of Quibahá, those of Batenabá, Acul-Uinák, Balamihá, the Canchahéles, and the Balám-Colób. (..) They multiplied there [in the darkness] in the east as well. (..) They all lived together and roamed in the east. (..) There were many dark and light-skinned people. (..) They had a single language.’ They observed the morning star Venus and awaited the (new) sun.

Second part

With the ‘creation of man from corn,’ the mythological primordial time transitions into a more legendary account of the deeds of the first ancestors, their wanderings, and wars, leading to the foundation and further fortunes of the K’iché kingdom.

Tula

The four patriarchs, Balam-Quitzé, Seawater was his wife, Balam-Acab, Springwater was his wife, Mahucutáh, Hummingbirdwater was his wife, and Ixqui-Balám, Parrotwater was his wife, of the ‘Ahau Quiché’s’ had heard about a city, Tula(n), Seven Caves (the Aztec Chicomoztoc, ‘seven caves’), Seven Gorge, where they journeyed through the ‘darkness of the night’ on a long wander. They desired the great star, the ‘sun bearer’, ‘sun bringer’, (Venus the Morning Star), the ‘birth of the sun’, to see. The Tamub and Ilocáb also went there. There they received their gods: Tohil (Quetzalcoatl), Avalix, Hacavitz, and Nicahtacáh. The three K’iché tribes united under their common god Tohil. Different tribes gathered in Tula: the Rabinal, Cakchiquels, those of Tzikinahá, and Yaqui. In Tula, their languages changed, so they could no longer understand each other because, in Tula, the tribes separated. The people were poor, wore only animal skins, had little food, and had no fire. Tohil gave them fire. Due to heavy rain and a hailstorm, the fire went out again, and the tribes asked the K’iché’s, who alone received fire for the second time from Tohil, for fire. ‘Are we not from one root, were we not created and formed on the same mountains?’ Tohil stipulated that the other tribes also united with him. The tribes were sacrificed, humiliated, and subjected to the K’iché’s. Then the K’iché’s ‘left the east behind,’ they ‘set out [from] the east.’

Hacavitz

The Quiché or Kʼicheʼ people gathered on the mountain ‘Place of the council’ and went through ‘the parting sea’. They called the place ‘Quicksand’. They sought out forests to hide the god statues of Tohil, Avilix, and Hacavitz, which they had been carrying in ‘nets of lianas’ since they had departed from the Tulan cave, there in the east. Hacavitz disappeared ‘into a naked mountain,’ and there they awaited the sunrise. Then ‘they brought out the incense that they had brought from the east for this moment.’ The sun appeared. ‘And immediately the sun dried the face of the earth. (..) immediately the earth’s surface dried.’ The god statues turned into stone. On Mount Hacavitz, ‘they thought with sorrow of the east, from where they had come. They had been their hills, from where they had departed (..) There were also fishermen there in the east, the victorious Olmecs, we did not stay with them.’

The gods appeared as ‘youths’ when incense was offered to them, ‘as nagual they emerged from the rock.’ The four patriarchs, the offering priests, disappeared into the forest, terrorized the tribes, tore people apart, and wanted to sacrifice tribes to the gods. They received from the gods Patzilib, a blood-soaked skin, a sign from Tula. The human hunt began, and tribes were slaughtered. The gods bathed as youths in the ‘Bathing place of Tohil,’ and the tribes wanted to seduce them with three girls: Ixtáh, Ixpúch, and Quibatzunáh. But the gods gave the girls gifts, supposedly as proof that they had given themselves to the gods: three mantles, with the jaguar, the eagle, and bees and wasps painted on them. The prince of the tribes put on the mantles, ‘paraded with his naked genitals before all eyes,’ and was then stung by bees and wasps from the third mantle. Thus, Tohil triumphed over the tribes. The tribes (‘more than 20,000 warriors’) rebelled and wanted to destroy the patriarchs, who had entrenched themselves with their families on the top of Mount Hacavitz. They wanted to worship Tohil but first ‘seize him.’ The attackers were first put to sleep, their weapons and jewelry were stolen from them, their eyebrows and beards were cut off. Then they marched to the top of the mountain. The patriarchs placed ‘insect hives’ in four large gourds at the corners of the palisade around their settlement, behind which wooden armed dolls were arranged. The warriors were defeated by the insects when the lids of the gourds were lifted, and slaughtered. All the tribes submitted. Hacavitz was the first settlement.

Balam-Quitzé had two sons: Co Caib and Co Cavib. Balam-Acab had two sons: Co Acul and Co Acuték. Mahucutáh had a son: Co Ahau and Iqui-Balám had no sons, ‘he was a true offering priest.’ The patriarchs left and left behind a ‘sign of the covenant,’ Pisom K’ak’al, a seamless scroll consisting of many cloths. ‘So the people descended from these lords. (..) the first people who came across the sea from the sunrise.’ Now, it was decided by Co Caib (of the Cavéc house), Co Acuték (of the Nihaib house), and Co Ahau (of the Ahau Quiché house) to journey to the east, ‘to the other side of the sea’. The three sons went to Nacxit (Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl), the ‘lord of the sunrise.’ They received from him the signs of royal power and ‘they brought across the sea the scripture from Tula. They called it the Scripture, in which their history was recorded.’ The three sons returned, and after the four wives of the patriarchs had died, other mountains were sought to settle.

Santa Cruz

Chiquix became the new city, and on four hills, cities with the same name appeared. Then came the cities of Chiquix, Chicác, Humetahá, Kulbá, and Cavinál. The sons of the patriarchs died. The ‘elders and the fathers’ united in the hilly city of Chi Izmachi. There were three great families, from the Cavéc, Nihaib, and Ahau Quiché houses. The Ilocáb rebelled but were captured by King Co Tuhá. During that time, the custom of sacrificing people for the god statues began. Three generations ruled over the city of Izmachi. Then came the city of Cumarcaáh (the Aztec Utatlan, Santa Cruz del Quiché) under the kings Co Tuhá and Gucumátz, where the three houses were divided into nine families and the empire was divided into twenty-four subdivisions (and twenty-four ruling houses). Then Chichicastenango emerged. Driehert and Negenhond, the twelfth royal lineage of the Cavéc house, ruled when the Spanish conqueror Pedro de Alvarado arrived. They were hanged by the Spaniards. Don Christóbal was the ruler of the Nihaib house at the time of the Spaniards.

The end of the Popol Vuh reads: ‘There is nothing more to see. The old wisdom of the kings has been lost. Thus everything comes to an end in Quiché, which is called Santa Cruz.’

Background

The mythological part of the Popol Vuh has a great depth of time. Main characters such as the Heroic Twins, Howler Monkey gods, and underworld gods were already significant in the Classic Maya civilization (up to 900 AD) and were frequently depicted on painted pottery. One of the heroic twins, Hunahpu, had a direct connection with the then-kingship (see Ahau). The extent to which the adventures of the classic heroic twins coincided with those of the Quichean is a contentious issue.

Impact in the present

Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg already labeled the Popol Vuh as ‘the holy book’ in 1861. This implicit comparison with the holy books of Jews and Christians is not entirely accurate. First of all, the Popol Vuh as a whole does not have a universal edifying purpose, and secondly, the mythological part of the Popol Vuh, as far as is known, was not an inviolable, essentially unchangeable text like the Bible. However, in the struggle for their own cultural identity, the text has indeed become a kind of holy book for many modern Maya and a new, pan-Mayan life has begun. Translations into other Mayan languages than just K’iche’ have contributed to this. Although the Popol Vuh is considered national heritage by all Guatemalans, for these Maya and their organizations, it represents their quintessentially own.

History

The Popol Vuh, also known as the Book of the Council, is a book that treasures much of the wisdom and many of the traditions of Mayan culture, primarily established in what is now Guatemala. It is a comprehensive compendium of aspects of great importance such as religion, astrology, mythology, customs, history, and legends that recount the origin of the world and civilization, as well as the many phenomena that occur in nature.

The text of the Popol Vuh is preserved in a bilingual manuscript written by Friar Francisco Ximénez, who identifies himself as the transcriber (of the version in Quiché Maya) and translator of an ancient “book.” Based on this, the existence of a work written around the year 1550 by an indigenous person who, after learning to write with Latin characters, captured and wrote down the oral recitation of an elder, has been postulated. However, this hypothetical author “never reveals the source of his written work and instead invites the reader to believe whatever they want from the first recto folio,” where he affirms that the original book “is no longer seen” and uses the expression “painted” to describe it. If such a document existed, it would have remained hidden until the period 1701-1703, when Ximénez became the doctrinal curate of Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (Chuilá).

Friar Francisco Ximénez transcribed and translated the text into parallel columns of K’iche’ and Spanish. Later, he elaborated a prose version that occupies the first forty chapters of the first volume of his History of the Province of Santo Vicente de Chiapa and Guatemala, which he began writing in 1715.

Ximénez’s works remained archived in the Convent of Santo Domingo until 1830 when they were transferred to the Academy of Sciences of Guatemala. In 1854, they were found by the Austrian Karl Scherzer, who in 1857 published Ximénez’s first carving in Vienna under the original title The Stories of the Origin of the Indians of this Province of Guatemala.

Abbot Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg stole the original manuscript from the university, took it to Europe, and translated it into French. In 1861, he published a volume under the title Popol Vuh, le livre sacré et les mythes de l’antiquité américaine. It was he, therefore, who coined the name Popol Vuh.

Brasseur died in 1874 and left his collection to Alphonse Pinar. He showed little interest in the Central American area and sold the collection in 1883 to raise funds for other studies. The original manuscript by Ximénez was purchased by collector and businessman Edward E. Ayer, who resided in Chicago, United States. As a member of the board of directors of a private library in Chicago, he decided to donate his collection of seventeen thousand pieces to the Newberry Library, a process that lasted from 1897 to 1911. Three decades later, Guatemalan ambassador Adrián Recinos located the manuscript in the library and published the first modern edition in 1947. Today, a facsimile of the manuscript is available online thanks to a collaboration between the Newberry and the Library of Ohio State University, under the direction of Professor Carlos M. López.

The town of Santa Cruz del Quiché was founded by the Spanish to replace Q’umar Ka’aj, the ancient capital of the K’iche’ kingdom. Juan de Rojas and Juan Cortés are cited in the book as the last members of the generation of K’iche’ kings.

Origin of the Narratives

The first researchers assumed that the Popol Vuh had been written in the Mayan language with Latin characters, thus collecting the existing oral tradition in the 16th and 17th centuries. The mention in the genealogies of characters from the post-conquest period undoubtedly indicates that the work as it exists today is also posterior to the Hispanic presence in the area.

René Acuña, like other scholars, doubted that the content reflected in the Popol Vuh was truly Mayan because he points out that “the Popol Vuh is a book designed and executed with Western concepts. Its compositional unity is such that it allows us to postulate a single collector of the narratives, it does not seem that this was a spontaneous native autodidact who wrote down the memories of his nation.” This theory is based on certain transcription errors that Ximénez commits when translating the text, revealing his unfamiliarity with the K’iche’ language. For example, the analogies with the biblical book of Genesis, although mixed with purely Mesoamerican concepts, have raised suspicions both of clerical intervention in its composition and of the result of a process of acculturation.

Regarding this, Acuña points out: “If the fidelity with which Ximénez copied and translated the K’iche’ text were the criterion for establishing the authenticity of the Popol Vuh, it would immediately have to be declared false […] Enumerating in detail all the inaccuracies that Ximénez introduced could justify a work of pages whose number cannot be quantified […] Faced with the impossibility of carrying out here a detailed examination of the translations that Ximénez made of the Popol Vuh, I will have to limit myself to saying that they are unequal and very unfaithful and that the friar omitted translating a high percentage of the text. My assessment is based on the meticulous comparative analysis I have carried out of the first 1,180 lines of the Popol Vuh with Fray Francisco’s two Spanish versions. But my intention is not aimed at discrediting the linguistic competence of this religious, but rather at highlighting that, with the scarce knowledge of the K’iche’ language that he possessed, it is natural that he would have disfigured the work when copying it.”

By questioning Ximénez’s ability to handle the Mayan language, a logical doubt arises as to whether the Popol Vuh is an original Mayan text, since only the version of said religious text is currently available. In this same line of thought, John Woodruff, another critic, has come to the conclusion that “the extent of the interaction that Ximénez has with the text is not sufficiently established […] and without discussing what could constitute an authentic indigenous discourse, at least some of the ideas contained in the first recto folio can be identified as not entirely indigenous.” On his part, Canto López comments that it is possible to question the existence of an original book of pre-Hispanic origin, which would lead to the logical conclusion that it was written with the support of oral tradition.

However, some archaeologists have endeavored to find evidence of the narratives of the Popol Vuh in the Mayan hieroglyphs of the pre-Hispanic period.

Popol Vuh is a bilingual compilation of mythical, legendary, and historical narratives of the Maya K’iche’ or Quiché people, the indigenous people of present-day Guatemala with the largest population. This book, of great historical and spiritual value, has been called the Sacred Book of the Maya. In contemporary K’iche’ orthography, the book is called Popol Wuj, following the norms of the Academy of Mayan Languages of Guatemala.

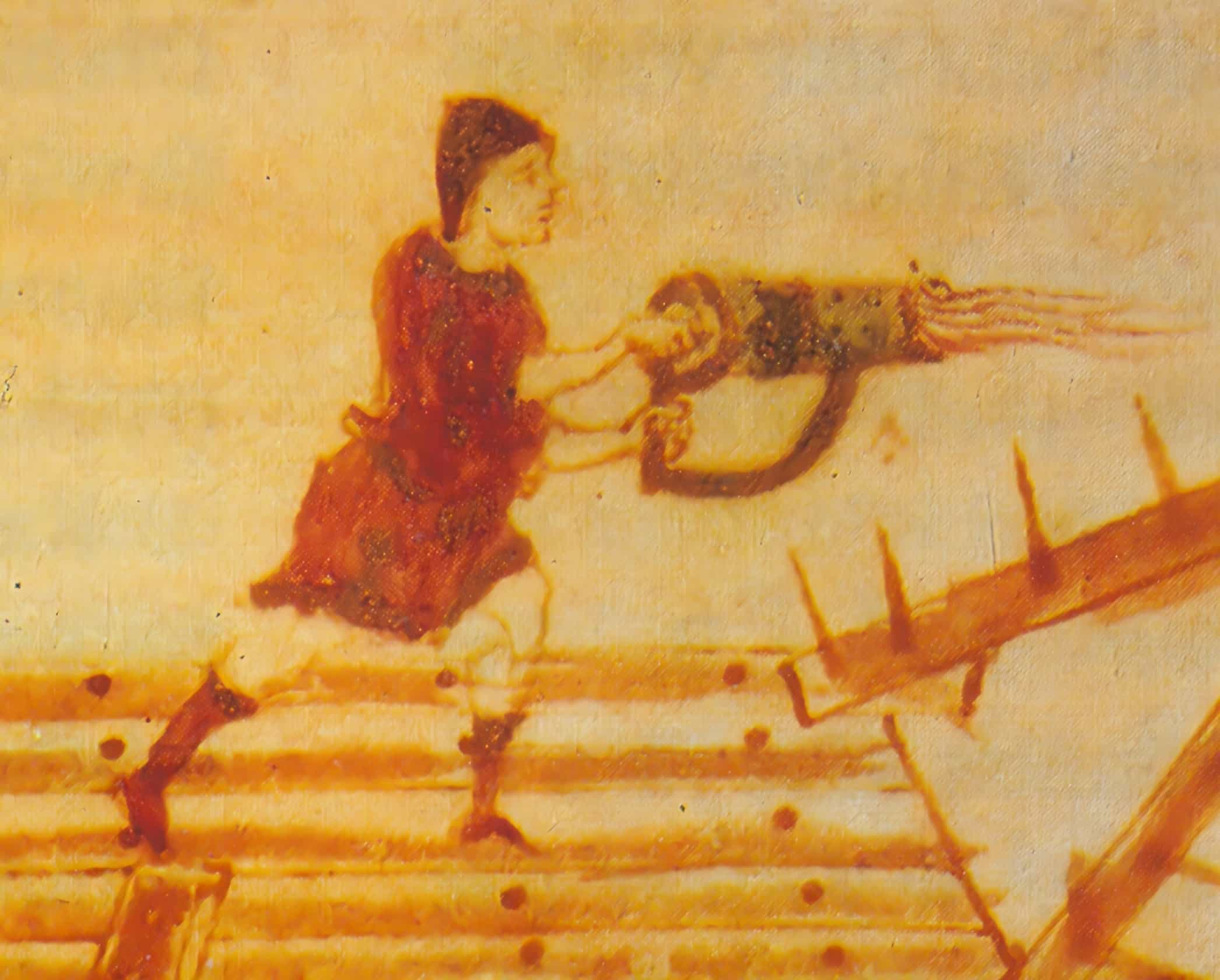

Discovery of Popol Vuh Mural in El Mirador

During investigations carried out in the city of El Mirador, a team of archaeologists led by Richard D. Hansen from Idaho State University discovered a panel with one of the oldest representations of the creation beliefs according to the Mayans: the Popol Vuh. The sculpture dates back to approximately 200 BCE and depicts the mythical twin heroes Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué, swimming in the underworld to retrieve the decapitated head of their father. The sculpture dates from the same period as some of the oldest works related to the Popol Vuh: the murals in San Bartolo and the Nakbe stela, two nearby cities. Archaeologists installed a climate-controlled shed over the newly discovered area to prevent the structure from being damaged.

The sculpture adorns the wall of a canal intended to channel rainwater through the administrative area of the city; moreover, every roof and plaza in the city were designed to direct rainwater towards collection centers. This water collection system would have been one of the reasons why El Mirador became the first powerful Mayan kingdom and would represent one of the oldest examples of the myths described in the Popol Vuh.

Synopsis

The Popol Vuh encompasses a variety of themes including creation, ancestry, history, and cosmology. There are no content divisions in the Newberry Library’s holograph, but generally popular editions have adopted the organization introduced by Brasseur de Bourbourg in 1861 in order to facilitate comparative studies. Guatemalan writer Adrián Recinos explains that: “The original manuscript is not divided into parts or chapters, the text runs without interruption from beginning to end. In this translation, I have followed Brasseur de Bourbourg’s division into four parts and each part into chapters, because the arrangement seems logical and in accordance with the subject matter and meaning of the work. Since the version by the French abbot is the most well-known, this will facilitate the work of those readers who wish to make a comparative study of the different translations of the Popol Vuh.”

Creation

- The gods create the world.

- The gods create the animals, but since they do not praise them, they condemn them to eat each other.

- The gods create beings from clay, which are fragile and unstable and fail to praise them.

- The gods created the first humans from wood, these are imperfect and lacking in feelings.

- The first humans, who become monkeys, are destroyed.

- The twin heroes Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué try to kill the arrogant god Vucub Caquix, but fail.

- Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué kill Vucub Caquix.

Stories of Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué

- Ixpiyacoc and Ixmukané engender two dwarfs.

- Hun Hunahpú and Ixbakiyalo engender the twins Hunbatz and Hunchouén.

- The Lords of Xibalbá kill the brothers Hun Hunahpú and Vucub Hunahpú, hanging the head of the former (Hun Hunahpú) on a tree.

- Hun Hunahpú and Ixquic engender the twin heroes Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué.

- The twin heroes are born and live with their mother and paternal grandmother Ixmukané, competing with their half-brothers Hunbatz and Hunchouén.

- Hunbatz and Hunchouen turn into monkeys.

- Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué use magic to cut down trees.

- A rat speaks to Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué and tells them the story of their ancestors.

- The Lords of Xibalbá call Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué to the underworld.

- Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué survive the tests of the underworld.

- Hunahpú is killed by bats, but his brother resurrects him.

- The twin heroes commit suicide in the flames and their bones are left abandoned in a river.

- Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué come back to life and murder the Lords of the Underworld.

- Hun Hunahpú returns to life through his son.

Creation of the Corn Men

- The first four real men are created: Balam Quitzé, the second Balam Akab, the third Mahucutah, and the fourth Iqui Balam. They are made of corn.

- The first four women are created.

- They began to have children and raise their generation.

Waiting for Dawn and Stay in Hacauitz

- Venus rises, followed by the birth of the sun, causing great joy.

- The deities turn to stone (only the elf Zaquicoxol escapes).

- The four K’iche’ men remain hidden in the mountain.

- By order of Tohil, the patron god of the K’iche’, the kidnappings of other tribes begin to carry out human sacrifices to this deity.

- The other tribes, desperate due to the kidnappings, send four beautiful girls to seduce the men and achieve their defeat, but they are deceived by four magic mantles.

- The other tribes send an army to defeat the K’iche’ men hiding in the mountain, but before reaching it, they fall asleep induced by Tohil, and the four K’iche’ men steal their war instruments.

- Death and advice of Balam Quitze, Balam Akab, Mahucutah, Iqui Balam.

- Balam Quitze leaves his descendants, the K’iche’, the “Pizom Kakal,” or “Sacred Wrapper,” which will serve as a symbol of their power.

Migration Stories

- The children of the first K’iche’ parents return to Tula, where they receive the symbols of power from Nacxit. Upon their return to Mount Hacauitz, they are received with signs of joy.

- They embark on a migration in search of the mountain where they will finally settle and find a city. In Chi Quix, some groups split. They pass through Chi Chak, Humeta Ya, Qulba, Cauinal, and Chi Ixmachi.

- In Chi Ixmachi, the first war erupts, motivated by the deception of the Ilocab group to Istayul. Finally, the Ilocab are reduced to slavery.

- The power of the K’iche’ grows, causing fear among other peoples.

- The three main tinamit of the K’iche’ Confederation are formed: Cauiquib, Nihaib, and Ahau Quiché.

Foundation of Gumarcah and List of Generations

- They found the city of Gumarcah, near present-day Santa Cruz del Quiché, in the Quiché department.

- The 24 “Great Houses” are founded, becoming important units of sociopolitical organization.

- The conquests made by Quikab and Gukumatz, of prodigious nature, are narrated.

- The K’iche’ caueques expand their territory, conquering neighboring and distant peoples, who become tributaries.

- The different chinamit and “Great Houses,” as well as their main rulers until Juan de Rojas, who lived under Spanish rule, are named.

Main Characters

Tepeu-Gucumatz

Also called Tz’aqol-B’itol; Alom-K’ajolooom; Junajpu Wuch’-Junajpu Utiw; Saqinim Aq-Sis; Uk’ux Cho-Uk’ux Palo; Ajraxa Laq-Ajraxa Tzel. He is buried under quetzal feathers when Uk’ux Kaj comes to speak to him. He is what is before anything, amidst the darkness, pulsating. From him emerges the creative force, the first deity that then becomes increasingly distant. Seeks advice from other deities: Uk’ux Kaj and Xmukane, when it comes to creation, as he does not know how to do it. The creative impulse arises from this deity, which later in the narrative falls into oblivion.

Uk’ux Kaj-Uk’ux Ulew

Also represented as Jun Raqan; Kaqulja Jun Raqan; Ch’ipi Kaqulja; Raxa Kaqulja (and Nik’aj Taq’aj). In this sense, it is a triad, as the text says “It was of three essences, that of Uk’ux Kaj”. This deity is not present from the beginning, but “comes” to talk with Tepeu-Gucumatz, so it can be considered that it is posterior to Tepeu. Creation arises from the dialogue between the two. It remains active for a longer time than Tepeu, as later in the narrative it assists Junajpu and Ixb’alamke.

Xpiyakok, Xmukane

Also called Grandmother of the Day, Grandmother of Clarity, Rati’t q’ij, rati’t saq. According to Sam Colop, they were ajq’ijab’ (Mayan spiritual guides). They give advice on the creation of the stick men (the second failed creation). Later in the narrative, they are the grandparents of Jun Junajpu and Wuqub’ Junajpu. Although not mentioned directly, Xpiyakok contributes with Xmukane to the deception of Wuqub’ Kak’ix, saying they are doctors. They are wise but also naive. Their grandchildren deceive them to obtain the ball implements or when they turn their brothers into monkeys, for example. They do not show signs of being prodigious; rather, they are religious specialists who divine and burn incense when appropriate.

Wuqub’ Kak’ix-Chimalmat

Literally “Seven Macaw”. He became grand before creation. He claimed to be the sun and the moon, but it was not true; only his wealth shone: his silver eyes, his precious stones, the green gems of his feathers. It is not clear if he was a macaw or a man; he may have had characteristics of both, as he has a jaw, but at the same time, it is indicated that he “perches” (taqalik in the K’iche’ language) to eat the nances in the tree when he is shot down (like a bird) by the blowpipe of the boys. He behaved like a great lord, but only his riches gave him power, since when he is deceived, and these are taken from him, he dies. He could be a metaphor for those who are grand solely because of their material possessions, but he can also be (like his children) a representative of the error of pride alone.

Zipaqna

First son of Buqub’ Kak’ix, Zipaqna created mountains and volcanoes in one night. The text says that he literally played ball with the hills. He was a diviner, for he knew that the 400 boys wanted to kill him, whom he later murdered. He is defeated by Junajpu and Ixb’alamke, who bury him under what was his pride: a mountain.

Kabraqan

Literally “two feet” or “earthquake”, Kab’raqan knocked down mountains; with his feet, he made the earth tremble. He is deceived by the brothers Junajpu and Ixb’alamke with the promise of a mountain taller than all, which continues to grow. They give him a bird smeared with tizate (white earth), which weakens him, and so he is buried under the earth, under that which gave him pride.

Jun Junajpu, Wuqub’ Junajpu

The sons of Xmukane and Xpiyakok were apparently twins, although this is not explicitly mentioned in the text. Perhaps they were prodigious, but this is not clear since they do not perform any prodigy (except for the flowering of the morro tree in Xib’alb’a) and are easily deceived by those of Xib’alb’a. Jun Junajpu fathered two sons with Ixb’aqiyalo. Apparently, their only occupation was to play dice and ball. They held the title of rajpop achij. They were defeated in Xib’alb’a, in the House of Darkness, and their bodies were sacrificed and buried under the ballgame, except for Jun Junajpu’s head, which was placed on a tree that later sprouted and turned into a morro.

Jun B’atz, Jun Chowen

Sons of Jun Junajpu and Ixb’aqiyalo. They were flutists, artists, scribes, wise men, connoisseurs, blowgunners, sculptors, and goldsmiths. They were envious and mistreated their brothers Junajpu and Ixb’alamke, so they were deceived by them and turned into monkeys. In the narrative, it is mentioned that they were invoked by artists later as patron or protective deities.

Ixkik’

Daughter of Kuchuma Kik’, a lord of Xib’alb’a, she is a curious and impulsive maiden who approaches the forbidden tree by the lords of Xib’alb’a and speaks with the fruit-head of Jun Junajpu. She is also ingenious and brave when she finds a way to cheat her own death and ascends to the earth in search of her mother-in-law. There, she proves to be a good daughter-in-law, as she performs the impossible tasks her mother-in-law requests. Xkik’ and the prodigious pregnancy Xkik’ heard the tale of the tree fruit when it was told by her father Kuchumalkik’, the fruit of which was actually tasty, the one she heard about, so she walked alone and arrived at the foot of the tree planted in the ball court, Ixki’k wondered about the fruit, whether it was sweet, she thought she was not going to die or get lost, then she thought about cutting one. And then suddenly a skull among the branches of the tree spoke to her, it was the head of Jun Junajpu speaking to Xkik’, and asked her, don’t you want it? The head inquired, but the girl said she wanted it, the head asked her to extend her right hand so I can see it, said the head. Xkik’, convinced, extended her hand in front of the skull, so it squeezed and a bone saliva came out and went directly into the girl’s hand, and when she opened her hand there was no

bone saliva. The saliva carries her descent from Junajpu as a thinker, speaker, artist, ballplayer. When Xkik’ returned home, she carried Junajpu and Xb’alanke in her womb.

Junajpu, Xb’alamke

Sons of Jun Junajpu and Wuqub’ Junajpu, they are the main characters in the mythological section of the Popol Wuj. Their main characteristic is cunning and humility, for although they perform great feats, they never boast of them; on the contrary, they often perform them under the guise of simple blowgunners, poor people, or beggars. They carry out the wishes of Uk’ux Kaj, with whom they have constant communication. They are vengeful, as seen when they ceaselessly strive to defeat those from Xib’alb’a until they dismember them. They are prodigies by nature.

Jun Kame, Wuqub’ Kame

The two main lords of Xib’alb’a are wicked and deceitful. They and their kingdom are full of deception for anyone who descends into it, even if invited. They seek the destruction of Junajpu and Ixb’alamke, as they disturbed their rest with their ballgame. Apparently, they ruled over a large number of people, who were not necessarily dead, just as they themselves seemed to be alive, despite their macabre titles. This is proven when they are killed by the twins. They are proud and arrogant, which ultimately causes their downfall.

B’alam Ki’tze’, B’alam Aq’ab’, Majuk’utaj, Ik’i B’alam

The first created men set out for the mythical city of Tula, where they were given their respective deities. Except for Ik’i B’alam, they are the grandparents of the three great divisions, or amaq’, of the K’iche’: Kaweq, Nija’ib’, and Nima K’iche’. They are humble and obedient to the mandates of their respective deity, although often it is Tojil, the deity of the Kaweq, who speaks for all. They ensure the submission of other people by offering fire in exchange for their hearts. For this reason, they later kidnap the inhabitants of other villages to sacrifice them to their deities. Finally, they die leaving behind the Sacred Bundle to their descendants. They are faithful in fulfilling the wishes of their deities and ultimately die peacefully.

Tojil, Awilix, Jaqawitz, Nik’aj Taq’aj

Tojil is the tutelary deity who was given to B’alam Ki’tze’, the Ilokab’, Tamub’, and Rab’inaleb’ (under the name Jun Toj) in Tula. Awilix is the deity of B’alam Aq’ab’; Jaqawitz of Majuk’utaj; and Nik’aj Taq’aj of Ik’i B’alam. Nik’aj Taq’aj, like Ik’i B’alam, lacks protagonism and disappears in the later narrative. As for Awilix and Jaqawitz, although they are present throughout the story, they are often not mentioned, their names being replaced only by Tojil. They are vengeful deities, demanding the blood of people as tribute, and with it, they become more powerful and youthful. They guide the pilgrimage of the K’iche’ and direct them in their wars against other peoples.

As for their nature, perhaps they were animate beings before dawn, as with the rays of the sun, they became stone statues. If compared with Saqik’oxol, a similar deity who escaped petrification, it becomes clear that they were supernatural beings similar to those known as elves, with a physical presence but also immaterial, like the so-called owners of the current hills. In their stone state, however, these deities also manifested themselves as human beings. This is evident because it is mentioned that they went to bathe in the river, where they were seen by the villages, who tried to lose them through fornication, implying that they also had a physical nature.

K’oka’ib’, K’o’akutek, K’o’ajaw

Sons of the three first fathers, they set out eastward where Nacxit gives them the emblems of power and authority. They are the ones who move to and reign justly in Chi K’ik.

Q’ukumatz-K’otuja

Q’ukumatz was a character who reigned alongside K’otuja. According to the text, he belonged to the fourth generation of another character also known as Q’ukumatz. He is a portentous being, taking the form of a serpent, eagle, jaguar, and resting blood. He initiated a period of greatness for the K’iche’.

K’ikab’, Kawisamaj

They extended K’iche’s dominance by conquering the Kaqchikel and the Rab’inaleb’. They extended their domains to Mam territory as well, in Xe’laju and Saqulew. They made tributaries of the conquered peoples, brutally repressing those who refused their expansion. They razed cities and wiped out entire lineages. They also secured the villages they were conquering so that they could not be taken back. They were great warriors and consolidated the expansion and image of the K’iche’.

Fragments

Creation of the World and the First Attempts to Create Men

The Popol Vuh recounts the nonexistence of the world until the creator and former decided to generate life. The intention was for his own creations to be able to speak to him and thank him for life. First, the Earth was created, then the animals, and finally, men. These were initially made of clay, but as the attempt failed, the great creator and former decided to fashion them from wood. Once several families were established, the creator and former, fearing that his creatures might be tempted to supplant him in wisdom, diminished the sight and intelligence of the eight gods

The Creation

This is the account of how all was in suspense, all calm, silent; all still, silent, and the expanse of the sky empty.

This is the first relation, the first speech. There was not yet a man, bird, fish, crab, tree, stone, cave, cliff, herb, or forest: only the sky existed.

The face of the earth was not yet manifest. Only the sea was calm and the sky in all its extent. Nothing was together, making noise, or moving, or stirring in the sky. Nothing stood upright; only the water at rest, the calm sea, alone and tranquil. Nothing was endowed with existence.

There was only stillness and silence in the darkness, in the night. Only the Creator, the Former, Tepeu, Gucumatz, and the Progenitors were in the water surrounded by brightness. They were hidden under green and blue feathers.

Here then came the word, Tepeu and Gugumatz came together, in the darkness, in the night, and spoke to each other Tepeu and Gugumatz. They spoke, therefore, consulting with each other and meditating; they agreed, they joined their words and thoughts. Then it was clearly manifested, while they meditated, that when dawn came, man should appear. Then the creation and growth of the trees and vines and the birth of life and the clarity in action of man were arranged. Thus it was arranged in the darkness and in the night by the Heart of

the Sky, which is called Hurricane.

The first is called Caculhá Hurricane. The second is Chipi-Caculhá. The third is Raxa-Caculhá. And these three are the Heart of the Sky.

Then Tepeu and Gugumatz came together; then they conferred about life and clarity, how it will be done so that it clears and dawns, who will be the one who produces food and sustenance.

“Let it be so! Let the void be filled! Let this water retreat and clear the space, let the earth emerge and firm up! So they said. Let it clear, let it dawn in the sky and on earth! There will be no glory or greatness in our creation and formation until there exists the human creature, the formed man.” So they said.

Then the earth was created by them. Thus it truly was how the creation of the earth was done:

“Earth!” they said, and instantly it was made.

Like the mist, like the cloud, and like a dust cloud was the creation, when the mountains emerged from the water; and instantly the mountains grew.

Only by a miracle, only by magical art was the formation of the mountains and valleys accomplished; and instantly the cypress and pine forests sprang up on the surface.

And thus Gugumatz was filled with joy, saying:

“Good has been your coming, Heart of the Sky; you, Hurricane, and you, Chípi-Caculhá, Raxa-Caculhá!”

“Our work, our creation shall be completed,” they replied.

First, the earth, the mountains, and the valleys were formed; the waterways were divided, the streams flowed freely among the hills, and the waters were separated when the high mountains appeared.

Such was the creation of the earth, when it was formed by the Heart of the Sky, the Heart of the Earth, which are thus called those who first made it fertile, when the sky was in suspense and the earth was submerged within the water.

Thus the work was perfected when they executed it after thinking and meditating on its happy completion.

Then they made the small animals of the forest, the guardians of all the woods, the mountain geniuses, the deer, the birds, lions, tigers, snakes, serpents, and rattlesnakes (vipers), guardians of the vines.

And the Progenitors said:

“Shall there be only silence and stillness under the trees and vines? Henceforth, there should be those who guard them.”

Thus they spoke when they meditated and immediately spoke. At once, the deer and birds were created. Then the deer and birds were assigned their abodes:

“You, deer, will sleep in the meadows by the rivers and in the ravines. Here you will be among the underbrush, among the grasses; in the forest, you will multiply, on four legs you will walk and have yourselves. And as it was said, so it was done.”

Then they also designated their abode to the small birds and the larger birds:

“You, birds, will dwell on the trees and vines, there you will make your nests, there you will multiply, there you will shake yourselves on the branches of the trees and vines.” Thus it was told to the deer and birds so that they would do what they were supposed to do, and all took their dwellings and nests.

Thus the Progenitors gave their dwellings to the animals of the earth.

And when the creation of all the quadrupeds and birds was completed, they were told by the Creator and Former and the Progenitors:

“Speak, cry out, chirp, call, speak each one according to your species, according to the variety of each one.” Thus it was told to the deer, the birds, lions, tigers, and serpents.

“Say, then, our names, praise us, your mother, your father. Invoke, therefore, Hurricane, Chípi-Caculhá, Raxa-Caculhá, the Heart of the Sky, the Heart of the Earth, the Creator, the Former, the Progenitors; speak, invoke us, worship us!” they said to them.

But they could not be made to speak like men; they only squealed, clucked, and squawked; the form of their language was not manifested, and each one shouted differently.

When the Creator and the Former saw that it was not possible for them to speak, they said to each other:

“It has not been possible for them to say our name, the name of us, their creators and formers. This is not right,” the Progenitors said to each other. Then they said to them:

“You will be changed because it has not been achieved that you speak. We have changed our minds: your food, your pasture, your dwelling, and your nests you will have, they will be the ravines and the forests, because it has not been possible to achieve that you worship us or invoke us. There are still those who worship us, we will make other beings that are obedient. You, accept your fate: your flesh will be ground up. So it will be. This will be your fate.” Thus they said when they made known their will to the small and large animals that are on the face of the earth.

Thus, a new attempt had to be made to create and form man by the Creator, the Former, and the Progenitors.

“Let’s try again! Dawn and the dawn are approaching; let’s make the one who will sustain and feed us! How will we be invoked to be remembered on earth? We have already tried with our first works, our first creatures; but it was not possible to achieve that we were praised and venerated by them. Let’s try now to make beings obedient, respectful, who will sustain and feed us.” Thus they made the human beings who exist on earth.

The Twin Gods: Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué

The Popol Vuh also recounts the exploits of the twin gods: Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué, who descended to Xib’alb’a (underworld) and defeated the Ajawab, and became the Sun and the Moon. Here is a fragment of the story of their birth:

When the day of their birth arrived, the young woman named Ixquic gave birth; but the grandmother did not see them when they were born. In an instant, the two boys named Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué were born. There, on the mountain, they were born.

Then they arrived at the house, but they could not fall asleep.

“Go throw them out!” said the old woman, because truly they cry a lot. And immediately they were placed on an anthill. There they slept peacefully. Then they were removed from that place and placed on thorns.

Now, what Hunbatz and Hunchouén wanted was for them to die right there on the anthill, or to die on the thorns. They desired this because of the hatred and envy they felt for Hunbatz and Hunchouén.

At first, they refused to receive their younger brothers into the house; they did not know them and so they were raised in the field. Hunbatz and Hunchouén were great musicians and singers; they had grown up amidst much toil and need and had gone through many hardships, but they became very wise. They were at once flute players, singers, painters, and carvers; they knew how to do everything.

They knew about their birth and also knew that they were the successors of their parents, those who went to Xibalbá and died there. Great sages they were, for Hunbatz and Hunchouén knew everything about the birth of their younger brothers. However, they did not demonstrate their wisdom, because of the envy they felt for them, for their hearts were filled with ill will towards them, although Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué had not offended them in anything.

The latter only occupied themselves with blowing darts every day; they were not loved by the grandmother or by Hun

batz or Hunchouén. They were not given food; only when the meal was finished and Hunbatz and Hunchouén had eaten, then they arrived. But they did not get angry or enraged, and suffered silently, because they knew their condition and understood everything clearly. They brought their birds when they came every day, and Hunbatz and Hunchouén ate them, without giving anything to either of the two, Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué.

The only occupation of Hunbatz and Hunchouén was to play the flute and sing.

References

- Akkeren, Ruud van (2003). Authors of the Popol Vuh (14). Ancient Mesoamerica. pp. 237-256. ISSN 0956-5361.

- Edmonson, Munro S. (1971). “The Book of Counsel: The Popol-Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala.” Middle American Research Institute (New Orleans, Louisiana: Tulane University) (35).

- Goetz, Delia; Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (1950). Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya By Adrián Recinos. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- López, Carlos M. (2007). “The Popol Wuj in Ayer MS 1515 Is a Holograph by Father Ximénez”. Latin American Indian Literatures 23 (2). pp. 112-41.

- Quiroa, Néstor Ivan (2002). “Francisco Ximénez and the Popol Vuh: Text, Structure, and Ideology in the Prologue to the Second Treatise”. Colonial Latin American Historical Review 11 (3): 279-300.

- Quiroa, Néstor Ivan (2001). The “Popol Vuh” and the Dominican Friar Francisco Ximénez: The Maya-Quiché Narrative As a Product of Religious Extirpation in Colonial Highland Guatemala. Illinois, USA: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Tedlock, Dennis (1996). Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. Touchstone Books. ISBN 0-684-81845-0.

- Woodruff, John M. (2011). “Ma(r)king Popol Vuh”. Romance Notes 51 (1): 97-106.

- Woodruff, John M. (2009). The “most futile and vain” Work of Father Francisco Ximénez: Rethinking the Context of Popol Vuh. Alabama, USA: The University of Alabama.

- Zorich, Zach (2010). “Popol Vuh Relief – El Mirador, Guatemala”. Archaeology Magazine (Archaeological Institute of America) 63 (1). Archived from the original on 1 March 2013.