A wide variety of occupations existed in the Middle Ages, as evidenced by not only administrative and financial texts, but also paintings, sculptures, stained glass windows, and illuminations (or sumptuous books). These occupations ranged from slave and serf labor provided to the domestic or salaried work of servants and companions, through the chores provided by peasants to their lords. The innovations that sprung from the trades of the Middle Ages set the beating heart of society in motion, driving it forward in its never-ending quest for new knowledge and methods of exploration.

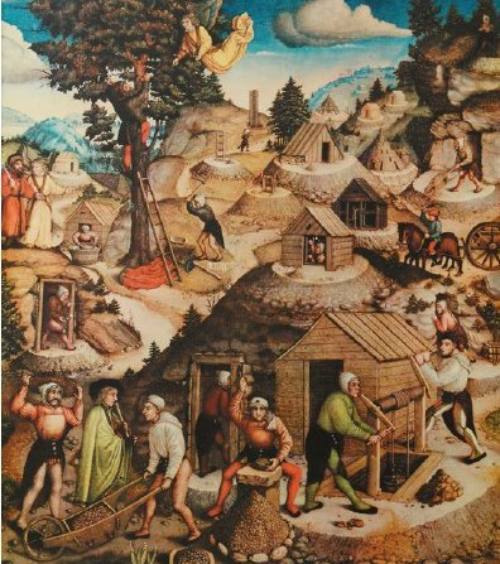

Miners

While it was disregarded in antiquity, sea coal was mined from English beaches in the early Middle Ages. Open pit mines or somewhat shallow galleries are still used for the extraction of rare earth coal. Diggers excavated the mine, carpenters cut timbers for the tunnels, and pickers mined the coal vein. Slaves and inmates were put in charge of the task due to the inherent dangers of the work (landslides, floods, a lack of oxygen, etc.).

The mines could only be opened by the wealthy and powerful (these were the “lords” of the mines from monks to rich merchants). Demand for metal increased in the 15th century, leading to the establishment of new mining communities all over the globe. Since the invention of water suction and air pumping, the job had become increasingly desirable. Between the years 1460 and 1530, European ore output grew by a factor of four.

The mined ore was broken up with a mallet, washed by hand with water, and then carried in baskets to the smelter, where it was combined with lime and cooked at a high temperature in the furnaces, with the impurities pouring out through an aperture on the surface of the molten metal.

Bloomery or Catalan furnaces were employed before blowers and blast furnaces made it possible to completely liquefy the metal. Their distinctive form resembled a half-buried hemispherical cap. Experts in the iron industry used purging furnaces to remove the carbon from the cast iron.

Iron cast in plates or sheaves was sold to blacksmiths exclusively by ironmongers, who also served as forge masters.

Blacksmiths

To forge and shape metal, blacksmiths used simple tools and equipment such as anvils, stoves, bellows, pincers, and hammers in cramped workshops. Charcoal was burned in the forge’s refractory earth construction, and the fire was maintained by bellows at its sides, which were pumped by apprentices.

Blacksmiths had high social standing in rural areas since they supplied weapons, armor, tools, household utensils, plowshares, sickles, and shovels, as well as shoed horses’ feet. Locksmiths installed and repaired locks, forged grails, chandeliers, and sometimes bells, but they also made clocks until clockmaking was attested as a specialization in 1483.

The gunners created the terrifying iron crossbow, while the cutlers fashioned blades and sharp weaponry.

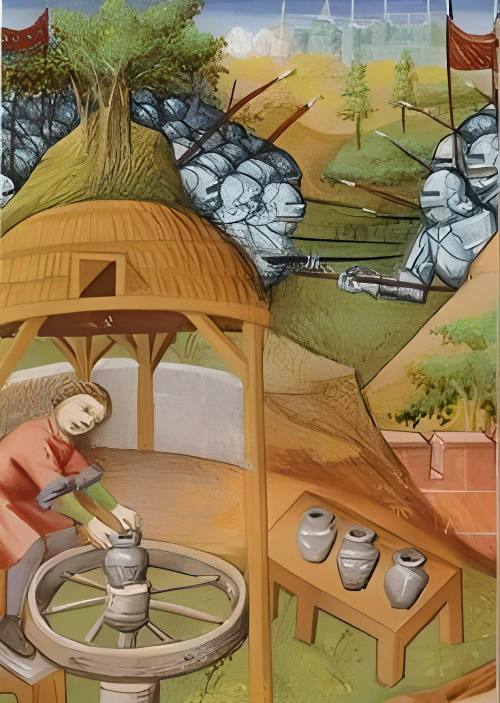

Potters, woodworkers, and salters

Numerous potters worked in rural areas throughout the Middle Ages. They often worked in families or small, rather impoverished artisan groups. In the 1st century AD, when there were no ovens, clay was shaped and baked outside. It wasn’t until the 9th century that these potters were widely used and output increased significantly throughout Europe.

Villages devoted only to pottery production sprung up over the world in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries; these settlements were situated on the outskirts of woods in order to have access to the wood needed for cooking. The carpenters and woodworkers worked together to construct half-timbered homes and shingle their roofs, while the woodworkers manufactured furniture such as tables, benches, and chests. That includes those who create clogs as well.

Due to its importance in the preservation of meat and fish and in the manufacturing of butter and cheese, salt production offered a livelihood for many Middle Ages people. It was harvested from salt marshes through evaporation. There were “salt houses” in the north of Europe, where salt was extracted from saltwater by boiling it in huge pots.

Stoneworkers and glassworkers

The stone was ripped from the cliff sides by the quarrymen using picks, then smoothed with hammers, cut with scissors, and polished with rasps. Since the stonecutter was paid per unit, they would engrave their marks on every piece. Stones were brought to the building sites by boat or cart.

Artists who worked in stained glass were one subset of the glassmakers, another was the glass artisan whose workshops were often located in close proximity to woods. Large amounts of wood were needed for the furnaces, and the work was difficult, hazardous, and required great expertise due to the high temperatures. While glass had been used since antiquity, it wasn’t until the 14th and 15th centuries that it really took off throughout Europe and beyond. Silica sand and beech ash made up the much-needed “glass paste.”

The history of glass is not a smooth one. Windows were originally crafted from materials such as parchment, greased paper, or mica. The wealthiest residents eventually upgraded their windows from oiled paper and parchment to glass panes.

Paper was often used for windows in ancient China, Korea, and Japan, but it was the Romans who introduced glass windows about the year 100 AD, and it didn’t become more popular until much later in the early 17th century. In the 13th century, the first glasses were created. It was about the year 1320 that the term “glass” began to be used to refer to the drinking vessels.

Developments in the glass business around the end of the Middle Ages included the invention of the blowing rod, or “punty,” and the coloring of the glass before cooking. In the 14th century, Venice emerged as a major rival to Bohemia as a glassmaking hub.

Builders

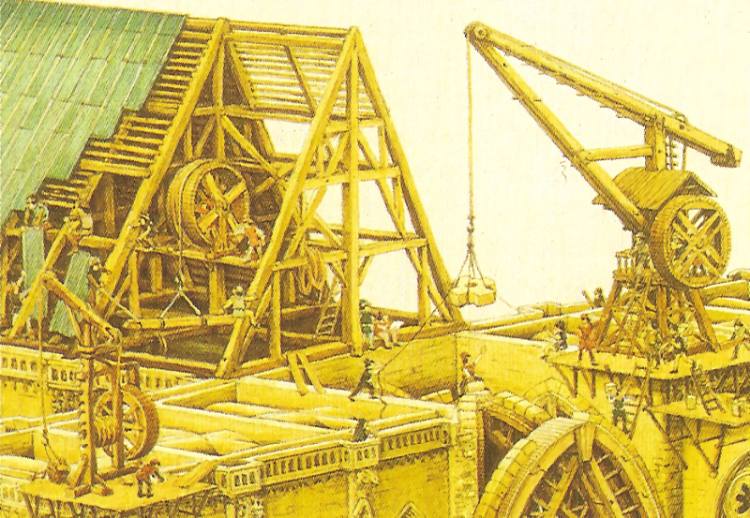

The building industry, which included tile makers, carpenters, bricklayers, pavers, and plasterers, grew as cities expanded and rulers and clergy became wealthy enough to construct palaces and churches. Over the ages, numerous new structures were constructed, ranging from the simple cob homes of laborers and craftspeople to the luxurious hotels of the affluent. The enormous churches were built over many years.

The building of Westminster Abbey in 1253 provides some indication of the variety of skilled laborers that would be required in the Middle Ages. There were a total of 59 skilled tradespeople tallied, including 39 stonemasons, 13 marble artisans, 26 masons, 14 glass workers, 4 plumbers, 32 carpenters, 19 blacksmiths, and numerous unskilled employees.

To be sure, the medieval laborers who built the cathedrals had a high level of expertise and were compensated accordingly. The building elite constituted the “upper” class of the construction industry, whereas the “lower” class masons only laid the stones.

The master builder (the term “architect” did not exist in the Middle Ages) was an experienced mason who had the expertise to lay out the blueprints and locate the ideal spot for the building’s foundation. A compass, a graduated ruler, a staff, and a pair of gloves were among the honorifics bestowed upon them. The installation of the stained-glass windows set with lead needed the expertise of glassmakers who were trained in the craft.

In the Middle Ages, medieval masons employed less framing and instead created makeshift wooden pathways that were supported by rafters placed into bolt holes so that the building could be occupied during construction. Who knows how many mishaps and fatalities could be traced back to this precarious approach.

At the tail end of the Middle Ages, cranes were often used in addition to a system of ropes and pulleys to lift the stones. There was not much change to the tools: a serrated hammer, a hammer for the stone, a plumb line, a trowel, and a square. The construction crew lived in a makeshift shack called a lodge, where they stored their belongings and coordinated their daily efforts. This practice resulted in the “statutes of the lodge” which masons began to follow it. Masons still use the term “lodge” in their constitutions and statutes today. The construction sites often dictated the schedules for all the various professions.

Specializations in the Middle Ages

In the tool industry, each trade had its own highly specialized craftspeople. Some of them made large scissors used to shear woolen fabrics. Traveling grinders were in direct competition with those using knives or brute force. The lorimers worked in tandem with the saddlers, producing components of horse harnesses such as spurs, stirrups, mounts, and anything in between. Some of them specialized in plate armor while others produced chain mail for horses.

The wheel rims were reinforced by iron hoops installed by the wheelwrights. Nails and locks were forged by the smiths, while old metal artifacts were recovered and recycled by the ironmongers, who were the forerunners of our modern scrap merchants.

Pewterers specialized in making decorative objects like mirrors and bells, as well as functional items like plates and cups. In the 13th century numerous other metals, including copper and bronze, were also put to use. Belt buckles and other common household items were crafted by copper foundries and molders. Copper was often used in candle holders and lamp bases created by skilled lamp builders.

The copper and bronze cookware came from boilermakers. Metal, from which plumbers took their trade name (from Latin plumbum, “lead”) was shaped by them for use in drainage systems, especially for gutters.

Attachers who created tiny nails used to adorn belts and harnesses, and the button makers who fashioned metal rosaries were just a few examples of the many specialized medieval artisans. The first button makers guild was formed in 1250 in Europe. The metalworking industry was fragmented into many tiny, often family-run businesses, and its members did not get much wealth with the exception of armorers. True artists, the coiners and goldsmiths were much sought after in both religious and secular courts.

Millers

Mills were iconic features of medieval landscapes; they employed the power of water to turn a vertical wheel mounted on an axis, which in turn turned a horizontal wheel attached to the stones to grind. Although water mills were originally used to grind grain and olives, their purpose and design evolved over the 12th century. It was used in a mill where cloth, iron, and paper were worked into shape.

It’s possible that the windmill has Asian roots. It’s a wooden structure with a metal base and three branches for support that houses the machinery and the grinding stones. The millers were notorious for their rapacity, so the lords often demanded a tax from the peasants who brought their grain to be ground.

Codes and regulations controlled the vast array of artisanal and commercial endeavors that flourished throughout the Middle Ages, and their diversity never fails to astonish us (the word “artisan” comes from the Italian word “arte” which implies a turn of the hand). Throughout the Middle Ages, men and women carried on and perfected the inherited tradesmanship that had been passed down through apprenticeship.

Food professions in the Middle Ages

Bakers and pastry chefs

In the countryside, every medieval household baked its own bread in the lord’s public ovens, but in most cities, where bread manufacture was monopolized by many different industries, this was strictly prohibited. Bakers had to work even on Sundays, and they couldn’t bake special cakes reserved for other guilds according to the statutes. Pastry chefs with their shops in the 13th century produced treats, cheesecakes, waffle-like pastries, or scalded pastries.

Furthermore, they dominated the market for meat and fish pies, which were all the rage in Medieval Europe (salmon, eel, pork fish, woodcock, lark, or quail pies). Street vendors sold their medieval wafers to passers-by on the sidewalk.

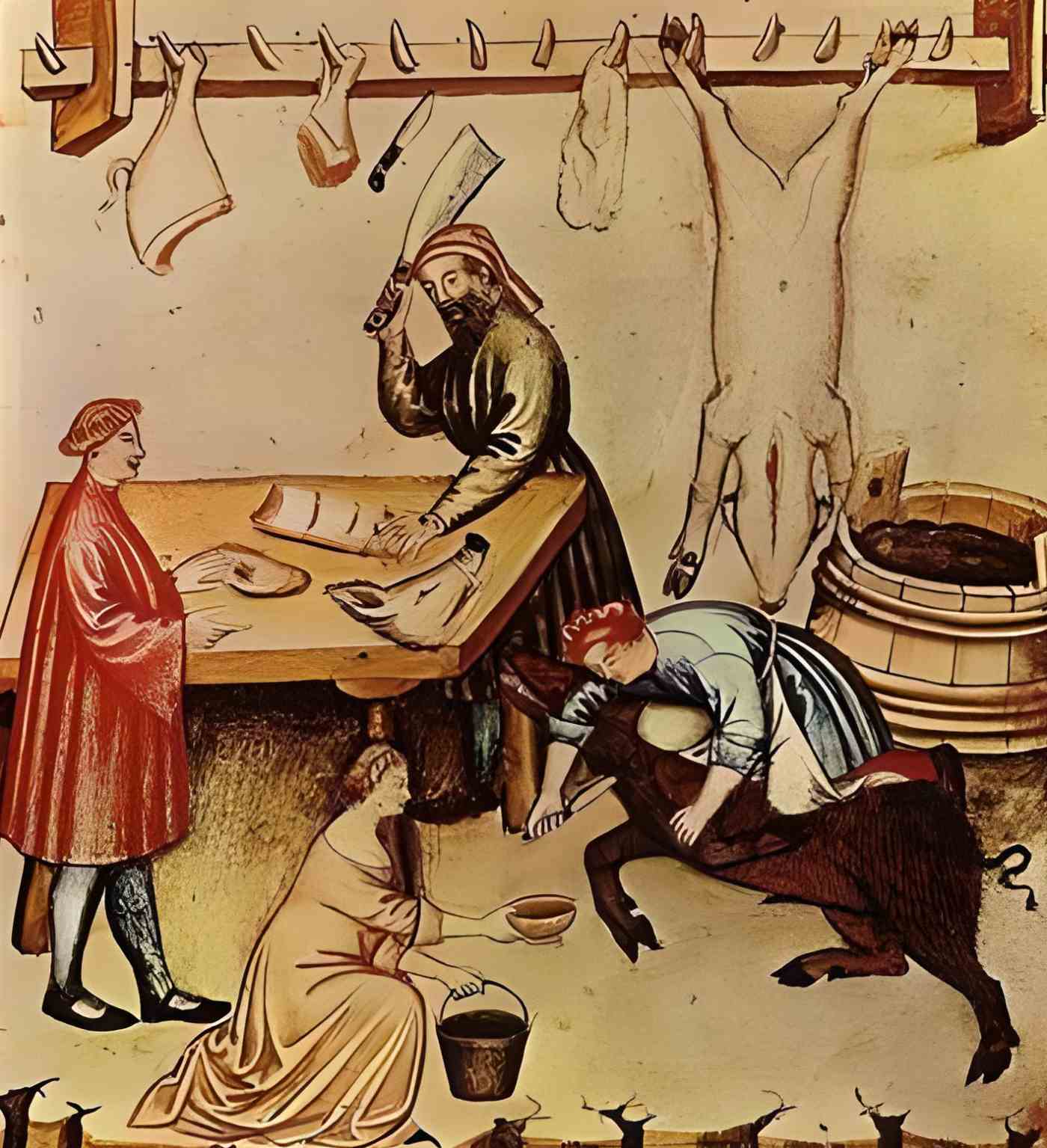

Butchers

People living in medieval cities ate a lot of meat, which made butchers successful despite their unsavory reputations owing to the street killing of animals and the resulting garbage. They cut lambs, goats, rabbits, chicken, goose, and partridges, while selling beef, fowl, veal, offal, and cold cuts.

Back in the 1300s, spice merchants helped customers disguise the flavor of rotten or too-bland meat. Street sellers were known to sell fruits and vegetables in addition to cheese, for which they were paid extremely badly.

Fishmongers

Since the late 1200s, Paris was home to three distinct groups of fishmongers: the King’s fishermen, freshwater fish merchants, and seawater fish merchants. During the time of Lent, many medieval people bought fish, especially herring and salted cod (salt allowed the preservation of fish as well as meat). Fish markets were the generator of waste and bad smells that the townspeople often complained about.

Innkeepers, taverners, hoteliers, and cabarets

Inns served as both homes and restaurants for weary travelers and pilgrims throughout the Middle Ages. These inns provided overnight accommodations and were distinguished by a sign. To draw in tourists or pilgrims, many inns were called after saints like St. James, St. George, and St. Catherine, or by catchy acronyms like “the hostelry of the angel,” “the three wise men,” “the red hat,” “the crown,” “the dish,” “the mermaid,” etc. Women, often widows, ran several of these lodging establishments. Medieval business deals and contracts were often struck at such locations.

Cabarets offered wine in pewter or tin cups on the roadside counter of their stall. The taverners sold wine by the barrel or the pitcher.

Crafting professions in the Middle Ages

Tanners

The tanneries’ foul odor was very disturbing in the Middle Ages. That’s why they were often located out of the ramparts. The skins were given a good scrub under running water, then shaved and conditioned with oil and alum. Tanners supplied the saddlers who made the leather coverings for the saddles, cobblers, glove makers, and bookbinders.

Cobblers got their name because they specialized in making shoes out of Cordovan leather, which was reserved for the upper classes. The glove makers employed exceptionally quality leathers such as deer, hare, or sheep skins, while the furriers sold furs from the Nordic nations.

The cobblers owed their name to the Cordovan leather with which they made the most beautiful shoes for the aristocracy, while the poor were content to call upon the cobbler. The glove makers used very fine leathers: kid, deer, hare, or sheep skins, while the shoemakers sold furs from the Nordic countries.

The rise of secular and religious bureaucracies, as well as the establishment of universities, paved the way for the expansion of the parchment industry.

Textile tradesmen

Fabric manufacture, including wool, was a major focus of medieval cities. Women beat the wool on racks to remove impurities and washed it in many baths to get rid of the wool grease that remains after shearing. The next steps were carding (in which the wool was put between two tiny rectangular wooden boards with handles and teeth) and spinning, both of which were common in rural areas and provided a means of subsistence for the local population.

The weight of the spindle caused a delicate rotation mechanism, which transformed the fleece (which was ready to be spun with the distaff) into thread. Once the spool of thread was built up, weaving commenced. The process started with the warping, when the warp threads were stretched over a casement.

Since the width of the woven pieces was restricted by vertical looms, it was not until the 11th century that horizontal looms were invented. The technique allowed for pattern production by having two workers, one on each side of the loom, sending a shuttle back and forth. The woolen fabric became unevenly grey and scratchy (it was used for horse blankets or for the poor and was called a quilt).

It still had to be washed many times, scraped with thistle to make it felt, trimmed to get rid of any lingering knots, and finally fulled by being trampled in vats of water and sand or wine lees to get rid of any leftover oil (the fullers were a group of poorly paid workers with poor working conditions). After that, medieval tradesmen could choose to sell the wool sheets in their natural state or dye them to match the current trends.

The sheets were submerged in dye, mordant, and alum baths, and the workers stomped them. Since the blue color was rare in nature, a pastel blue offered a highly sought-after shade of blue, boosting the economies of the communities that churned it out. For the pink, brazilwood was used; for the yellow and green, dyer’s weed (Reseda luteola); for the black, walnut husk; and for the red, cochineal insect.

Shaving the cloth again after it was colored improved its suppleness. So, in the Middle Ages, textile merchants specialized in five areas: weaving (including linen and hemp), shearing, fulling, dying, and tailoring. Cotton and linen, wool and linen, and wool and animal hair (rabbit or beaver felt) all arose at the end of the Middle Ages to create blended textiles.

In the Middle Ages, dressmakers, haberdashers, and hatmakers constituted the bulk of the medieval fashion industry’s consumer base. Embroiderers engaged in a kind of needle painting, while tapestry weavers were responsible for the magnificent wall hangings that adorned the medieval manors.

Intellectual and artistic professions in the Middle Ages

The majority of medieval teachers were clergy, and the church dictated education in the Middle Ages. Schoolmasters and schoolmistresses were often laypeople, and this practice began at the end of the Middle Ages. In the university cities, the profession of booksellers or “stationers” developed in the 13th century, working alongside parchment makers, scribes, or copyists to create literature meant for professors and students. Beautiful illuminated manuscripts (painted books with decorative metals) were ordered by wealthy nobility and clergy. In the 15th century, printers began popping up in the main cities in Europe and around the world.

A barber surgeon, trained via an apprenticeship, would shave patients, perform bloodletting and enemas, and use suction cups, whereas a medieval doctor, educated at a university, would simply examine the ill and prescribe a potion from the apothecary in the Middle Ages. The toothpullers, on the other hand, used big pliers to give their clients much-needed relief out in the public in full view (some even employed musicians to drown out their clients’ screams).

The minstrels, who were both storytellers and musicians, were typically organized into a corporation with a full hierarchy of masters and apprentices but were paid badly and not given any credit for their work.

With an eight- or ten-year apprenticeship, a goldsmith could become one of the most respected and well-paid professionals of the Middle Ages. Precious stones (ruby, emerald, diamond, rock crystal, etc.) used by goldsmiths in jewelry and silverware decoration were fashioned by lapidaries. They didn’t only make jewelry, however; they also made currency (royal coinage workshop). They were respected and powerful, to the point that no other creative field could compare.

Because only mental abilities were deemed valuable and rewarded (with a few notable exceptions) in the Middle Ages, artisans who worked with their hands were classed together in the “mechanical” arts, and given a lesser status than the “liberal” arts such as law, medicine, or theology.

Although most artists such as painters, sculptors, picture framers, and glassblowers learned their trade via an apprenticeship, their training did nothing to elevate them to the status of an artist. But those who carved bas-reliefs, tombs, recumbent figures, and stone sculptures for kings and the affluent in bone, boxwood, or ivory did well for themselves and were called “image carvers.”

The carpenters were responsible for making the wooden effigies. Murals, woodwork panels, and illuminations were all crafted by the painters, and they also created the designs for the stained glass windows. Glassmakers sketched out their designs in wet chalk on enormous tables the size of the glass window, drew on the sketch in “sinopia” (red ochre), and then put the colored glass plates in place with lead.

Apprenticeship, servants, and companions

A young person between the ages of 12 and 16 would be sent by their parents to live and work under a master under the terms of a contract sealed by a notary public. The master (who could ask for an admission fee from the parents to pay the kid’s costs) devoted his professional conscience throughout these years of instruction, which could span anywhere from two to twelve years.

During these years, the master took on the role of a parent, while the young lad devoted himself to labor without reluctance and to stay with his master until the conclusion of his contract, at the end of which he must produce evidence of his ability. When the evidence was excellent, it was not unusual to see a master leave his property or tools to his apprentice.

Few young men were able to go out on their own as business owners, and most remained “servants” to the person who had taught them. People called journeymen or boy servants could be hired for a variable period of one day, one week, or one year.

The journeymen banded together to stand up to their masters’ mistreatment, forming brotherhoods whose primary purpose was to provide aid in times of need. If tensions rose in a city, residents could decide to stage a mass exodus rather than return to work. Revolts sprang out as a result of these demands (the income disparity between bosses and employees only widened), but they were often put down violently and resulted in bloodshed.

The world of medieval trades and professions is not without modern echoes: the hierarchy within the job, the division of labor between men and women, the inequity of remuneration and working hours, all these themes are quite contemporary.

Documents from the Middle Ages reveal a humanity that is far from the anonymity of the Machine Age, while there were always individuals who were left out (unskilled laborers, beggars, and those with disabilities).

Bibliography

- Janet E. Burton, 1994, Monastic and Religious Orders in Britain, 1000-1300. Cambridge University Press.

- Christopher Dyer, 2009, Making a Living in the Middle Ages: The People of Britain, 850 – 1520. Yale University Press.

- Jenny Kermode, 1998, Medieval Merchants: York, Beverley and Hull in the Later Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

- Mark Bailey, 1996, “Population and Economic Resources.”