- “Protome” comes from Greek, meaning “front part” or “animal head.”

- They are decorative sculptures depicting the front or top parts of objects.

- Protomes are dating back to Neolithic times and have been found in various cultures.

A protome is a sculpture in art history that depicts the head and shoulders of an animal or person and is often paired with another item. It is a decorative feature that can be painted, sculpted, or engraved and was often utilized in ancient art. In architecture, it may be found on brackets, cornices, and pediments; in decorative arts, on utensils, containers, armor pieces, sculptures, ceramics, jewelry, coinage, furniture, etc.; and in literature, in the form of heads and busts of real or imagined characters.

Origin of the Word Protome

Protome (προτομή) means “the bust or head of an animal” and comes from the Greek words (pro- “front, before”; tomos- “part”), which literally translate to “the front part.” The protémno lies at the origin of this word, which means “to carve, amputate, cut.” It originally referred to an animal bellows still attached to its head.

In the field of ethnology, a protome is an animal mask used during rituals (like African initiation rites) or as a badge of honor. It may be a small piece of an animal, such as a piece of fur, claws, or teeth.

What is a Protome?

Whether it’s an animal, a legendary creature, or a person, protomes are sculptures that show the front or top body of the object. Masks, heads (with or without necks), busts, and portraits all qualify as frontal or upper body parts. They were often attached to vessels, equipment, jewelry, sculptures, or structures as adornments (appliques; ornamental needlework).

The Greeks valued female deity heads as independent works of art and presented them as votive offerings. By definition, many things are protomes, and they frequently go by their own distinctive names.

Busts, herms, masks, mascarons, angel heads, portrait medallions, gargoyles, attachments, and acroteria all fit this description when they are artistically executed.

Why Did Humans Create Protomes?

Few comprehensive studies have been conducted on the evolution of protomes. However, Ancient Greek, Persian, Roman, and Phoenician buildings, sculptures, and crafts often included them for decorative purposes.

There are three primary factors that led to the development of protomes:

- Giving the object a character — The difficulty of depicting legendary and magical entities on corbels, cornices, and other architectural elements that lack distinct and recognized iconography gave birth to the protomes.

- Creating a memory — Protomes have been used in art for historical and psychological reasons that are referred to as “the art of memory.” It was around this time that artists decided to solely show the faces of their subjects, whether human or animal. They thought that by emphasizing that, the viewers of the picture would be able to recall the whole animal or person. This method of creative expression attempted to communicate the importance of the topic by depicting just its head.

- The animistic view — The third most important factor is religion, which is tied to animistic worldviews. Protomes were used in ancient times with the belief that the symbolic attributes of the entities they represented would be transferred to the places and things in which they were placed. To express more nuanced symbolic meanings, ancient protomes began to fuse together previously distinct beings (humans and animals) to form chimeras, or, more accurately, using mythical creatures (such as flying bulls and horses, centaurs, and birdmen) to demonstrate the cultural mixing that occurred in Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, and Greece.

Protomes Throughout History

Despite the vast history of this ornament, art historians didn’t start using the word “protome” until the nineteenth century.

The Oldest Protome

The rams are the oldest example of protomes. Four rams’ heads etched on a sacrificial bowl from Neolithic Hungary’s Tisza culture in Szeged are the earliest protomes we have. Following these are a variety of Hittite workmanship items from the 15th to 13th centuries BC, and then a Minoan rhyton (a liquid container) with a bull’s head from the 16th or 14th century BC.

Throughout the Hellenistic period in ancient Greece, beginning in the 7th century BC, various protomes depicting both animal heads and human busts can be discovered on numismatic pieces such as coins and tokens.

Griffin, Snake, Lion, Bull, and More

Tripod bases for cauldrons were also adorned with protomes. Cauldrons from the 7th or 8th century BC were discovered at Olympia and Samos, and they were decorated with protomes of griffins and other animals. They might be inspired by bull protomes found on cauldrons from Urartu in the 8th century BC.

Cauldrons depicting snake protomes (Bernardini Tomb in Palestrina) and panther protomes (Regolini-Galassi Tomb in Cerveteri) have been unearthed in graves dating back to the 7th century BC in Etruria, central Italy.

For instance, the Phoenician settlement of Alcacer do Sal in Portugal has yielded bronze artifacts depicting protomes of felines, perhaps panthers. These likely served a spiritual purpose.

Protomes in the Ancient East

Protomes depicting bulls, lions, and griffins were discovered on jewelry, utensils, containers, and architectural large capitals in excavations at Susa and Persepolis dating back to the Achaemenid dynasty. A rhyton with a goat’s head is also housed at the Reza Abbasi Museum.

Meanwhile, Rudbar, in the northern Iranian province of Gilan, produced a decorated spherical clay vase from 900 BC with bovine protomes that can be seen now in the Iranian National Museum in Tehran.

The vast hall in which the Persian monarch entertained as many as 10,000 guests at Persepolis (about 521-465 BC) was decorated with a series of Persian columns topped with bull protomes.

Protomes at Darius I’s palace in Susa featured a variety of animal heads (gazelles, bulls, griffins, etc.) in order to impress and scare visitors. The ceiling was supported by protomes, which also had a symbolic and structural purpose by symbolizing authority and the harmony of the cosmos.

On the acroterion (an architectural ornament) of Persian cruise ships and Phoenician fishing boats (“hippoi” or horses) that sailed the Mediterranean, there was a customary practice of depicting a protome featuring the bust of a horse on the ship’s bow.

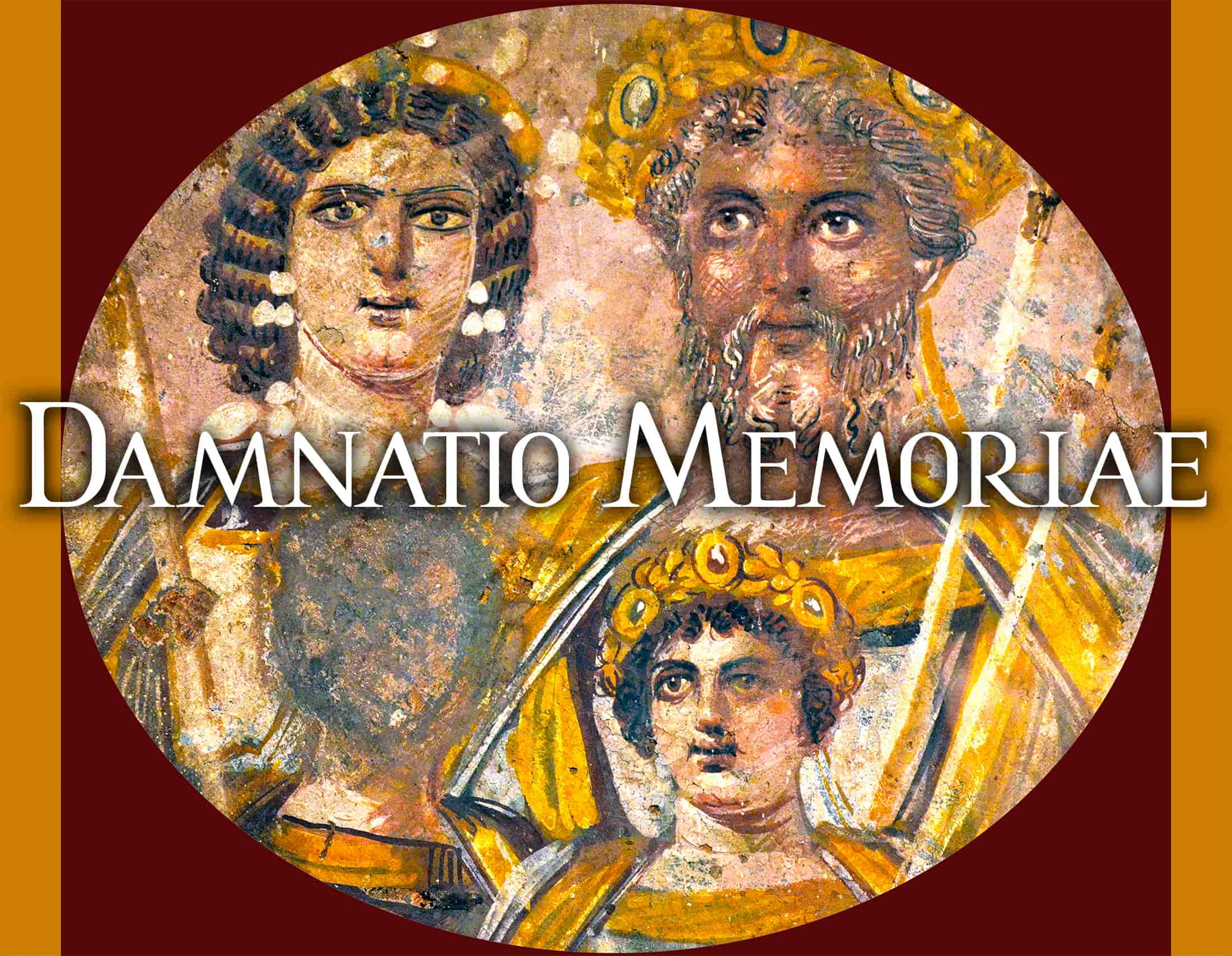

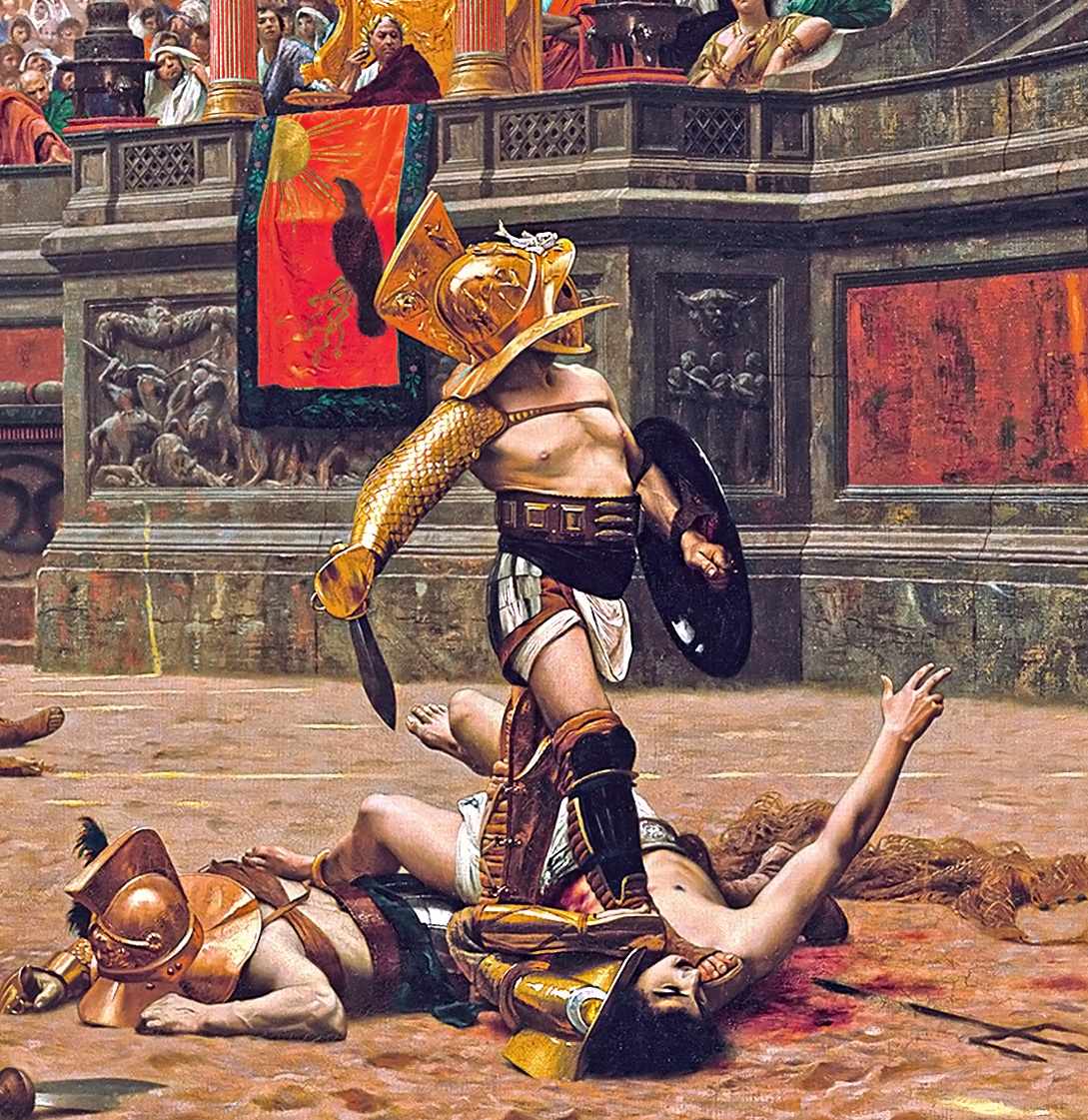

Protomes in Gladiators

Some gladiator helmets were also discovered to have the protome. It was usually placed at the face of the crest and included a variety of emblems.

The griffin protome was one of the most prevalent ones on gladiator helmets. The gods of vengeance were believed to travel with this creature in ancient times. The Hoplomachus gladiator is a popular example.

As shown on a Roman gladiator helmet from the 9th to the 12th century AD, the lion protome was a common decoration on several gladiator helmets.

Just as importantly, the Murmillo gladiators often fought in the arena with a fish protome on their helmets, and their fierce opponent, the Retiarius, was called a “fisherman” who fought with a fishing net.

References

- Photo, Gerd Leibrock, Creative Commons — Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported — CC BY-SA 3.0, enhanced from original.

- Bronze Monsters and the Cultures of Wonder – Google Books

- The Protome Painter and Some Contemporaries | American Journal of Archaeology: Vol 60, No 2 (uchicago.edu)