Why Were the Ancient Greeks So Educated and Enlightened?

Like any society, ancient Greek culture was diverse, encompassing more than just the distinctions between citizens, slaves, and foreigners living in Greek cities. The majority of citizens were not highly educated, and their interest in enlightenment was not particularly broad. Truly educated individuals belonged to a narrow circle of thinkers and wealthy citizens, primarily aristocrats. However, there were also plenty of ordinary laborers, crude soldiers, artisans, and citizens focused solely on their personal affairs.

- Why Were the Ancient Greeks So Educated and Enlightened?

- Did They Look Like Their Statues?

- By the Way, Why Are All the Statues Naked? Were the Greeks Not Ashamed of Anything?

- Did They Have Free Love, and Were All Men Homosexuals?

- Did Ancient Greeks Wear Underwear?

- Did They Really Dilute Wine with Water?

- What Did They Eat Besides Olives? Buckwheat?

- Did They Really Believe That Thunder and Lightning Were Zeus’s Anger, and That a Three-Headed Dog Awaited Them Underground?

- How Much Larger Was the Poor Population Compared to the Rich, and What Were the Relations Between Them?

- Were the Greeks as Warlike as the Vikings? Did They Often Engage in Warfare?

- Did They Invent the Olympic Games?

- Why Is Everything Ancient Still Considered the Most Beautiful by Many?

- Why Did Greece, With All Its Advantages, Not Become a Great Empire Like Rome?

- How Did Such a Vast Civilization Disappear?

What distinguished the Greeks was their near-universal literacy. It was impossible to exist in Greek society without knowing how to read and write, so all citizens either hired private tutors to teach their children literacy or taught them at home. Additionally, children became familiar with various poetic works. A deeper education required money and time.

Why, then, do we tend to think that all Greeks, or at least all Greek men, were universally educated thinkers? This misconception arises from the foundation of European education since the Roman Empire. It has been based on the texts of Greek and Roman authors, who often featured famous philosophers, scholars, or public figures as their heroes. This could create the impression that Greeks were constantly engaging in deep conversations. However, such discussions were only available to a narrow circle of intellectuals, while the topics of conversation among ordinary residents of Greek cities at a banquet or during a walk were not as elevated.

Did They Look Like Their Statues?

It depends on which statues we are talking about; Greek statues are very diverse. Some depicted gods or perfect athletes of the classical era; others showed orators and philosophers of the Hellenistic period; and still others were characteristic representations of ordinary people, such as an old fisherman or a drunken old woman. Faces in Greek art were conventionally portrayed symmetrically, and bodies were depicted as anatomically perfect, considering only the specifics of age (though there were exceptions).

Diversity was achieved through the unique features of the faces (symmetry was maintained, and unattractive details were not depicted) and the canons of depiction used by different sculptors. For example, the Argos sculptor Polykleitos in the 5th century BCE depicted young men with barely suggested anatomical details, while his contemporary Myron showed them more developed, as in older men.

To answer the question of which statues the ancient Greeks resembled, we need to know if modern Greeks resemble their ancestors. Physical anthropology suggests that the differences between ancient and modern Greeks are not very significant. However, while the faces may have been only slightly idealized, the bodies of ancient models certainly were not as perfect or physically developed. Statues aimed to depict the ideal human form, but reality was often quite different. Of course, occasionally, one might encounter an athlete with the physique of Apollo or a beauty with the body of Aphrodite, but such cases were rare. On the other hand, drunken old women and elderly fishermen were common, especially in the poorer neighborhoods of ancient Greek cities.

By the Way, Why Are All the Statues Naked? Were the Greeks Not Ashamed of Anything?

This is a misconception. First, not all Greek statues are naked, though many are. Second, this does not mean that the Greeks did not experience feelings of shame. They were as modest as modern people.

The question of why the Greeks favored depicting the naked body is quite complex. In ancient times, men worked naked in the fields—this custom was recorded by the poet Hesiod in the 8th century BCE. In the same century, runners began competing naked, and other athletes followed suit. According to legend, during the Olympic Games in 720 BCE, a loincloth fell off the runner Orsippos, and he finished naked. Another version of the legend states that the Spartan Akanthos started the race naked from the outset.

In any case, only men could be naked, and only under specific circumstances within their own circles: during sports, some religious rituals, etc. One hypothesis explains this shared nudity as a reflection of democratic thinking, which suggested that equal citizens should hide nothing from each other, including the intimate parts of their bodies. Statues emphasized the social role of the citizen, which is why their authors began depicting Greeks naked.

However, respectable women, including goddesses, were not allowed to be depicted naked. A female citizen of a polis could not appear in public without clothes. In artworks, only courtesans, dancers, flutists, and other women whose profession involved entertaining men during banquets were depicted as nude. In the 4th century BCE, the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles made a statue of a naked Aphrodite, which initially was not well received by the Greeks. It was said that he used his lover, the courtesan Phryne, as a model. However, over time, statues of a naked Aphrodite became popular.

Did They Have Free Love, and Were All Men Homosexuals?

No, and no. Rather, sexual relations among the Greeks were organized somewhat differently than in our society. In modern terms, Greek men could be described as bisexual, albeit with certain restrictions. For a married Greek man, it was unacceptable to engage in relationships with a free female citizen of the polis (although relations with a courtesan were possible). According to Athenian law, a lover caught in the act could be killed by the husband, and such precedents did occur. This does not sound much like free love.

However, outside the family, a man was not restricted in his sexual relations with women. Relationships with slave women were generally not taken seriously, and sexual relations with free non-citizens (metics) were not considered shameful. Courtesans, hired by men for entertainment during banquets or intimate encounters, often came from these non-citizen groups.

Homosexuality is more complex. For Greek men, it was normal to form sexual relationships with beardless youths up to the ages of 15–16, and such relationships were even encouraged as a form of mentorship. However, relationships between adult men were considered shameful and were often subjects of ridicule.

Nonetheless, this behavior was viewed more tolerantly than in many traditional societies.

When it comes to women, female citizens of Greek cities were restricted in their sexual relationships: they could only sleep with their husbands, and other relationships were strictly forbidden. At the same time, women sometimes imitated homosexual relationships with men: adult women formed relationships with young girls. The famous poet Sappho, who lived on the island of Lesbos, was known for such relationships—hence why homosexual relationships between women are called lesbian. However, Sappho’s writings are more about platonic rather than sexual love between women.

Did Ancient Greeks Wear Underwear?

No, the Greeks didn’t wear anything like underwear. Instead, loincloths were sometimes used as undergarments; slaves, craftsmen, and peasants wore them during work. However, loincloths were not always worn under clothes—they were used to keep warm or to protect the groin. True underwear, resembling modern bikinis or thongs with side ties, appeared in Roman times but was likely used only by women serving at feasts and perhaps during sports activities.

Did They Really Dilute Wine with Water?

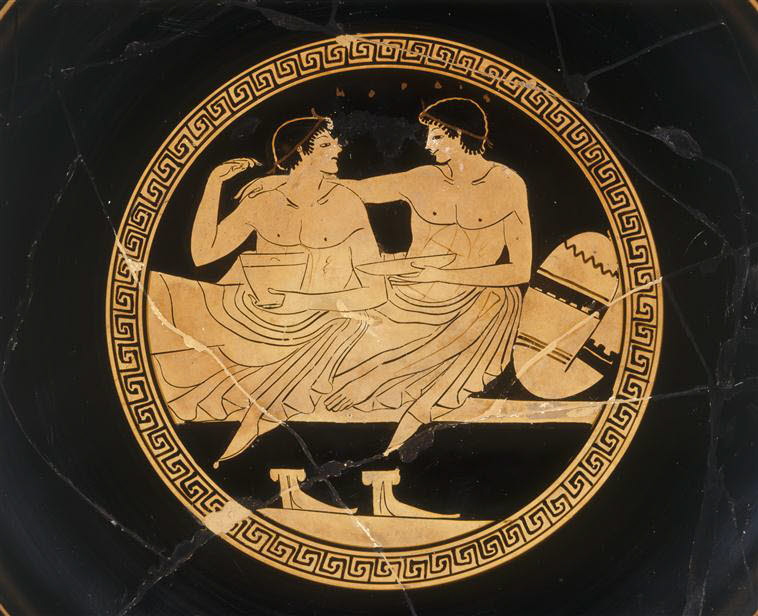

Yes, indeed, and sometimes quite heavily. A common practice was to dilute one part wine with two parts water, but it could go up to ten parts water. Considering that Greeks did not fortify their wine—that is, add alcohol to it—and it rarely contained more than 15% alcohol, diluted wine often became weaker than modern beer.

There are different explanations for the origin of this tradition: Greek authors merely state that diluting wine distinguished Greeks from barbarians. One might assume that diluting wine prevented participants at feasts from getting too drunk, but Greek vases often depict very drunk people, even vomiting. There is a theory that water from wells and cisterns could be of poor quality, and wine was used to disinfect it. However, further dilution reduced the alcohol content, lowering the antiseptic properties of the wine.

Most likely, Greek wine was significantly different from modern wine in its production technology. To increase the sugar content, grapes were slightly dried, resulting in a very sweet and thick drink. Additionally, they added seawater, crushed stone, and other ingredients to the wine; these helped prevent spoilage but made it cloudy. A strainer through which the drink was filtered was an essential attribute of a Greek feast.

However, in some circumstances, wine was not diluted, such as during cold weather when it was drunk as a medicine, at the beginning of a feast, or simply because someone liked its taste. Barbarians, on the other hand, drank undiluted wine to get drunk as quickly as possible, which Greeks considered inappropriate behavior.

What Did They Eat Besides Olives? Buckwheat?

Processed olives or olive oil were certainly not the only dishes on the Greek table. However, their cuisine was much less diverse compared to our modern diet. The most important staples in Greek nutrition were grains—wheat and barley. Wheat was used to make bread, and it was also used, like other grains such as millet or emmer, to make porridge. Unfortunately, the Greeks did not know about buckwheat; otherwise, they would have surely used it.

Another important food base was legumes. Large beans were unknown in Ancient Greece (they were brought from America much later), but they grew peas, lentils, and various types of vetch, which is now considered livestock feed. Legumes were used raw and as a base for thick stews. They also ate onions, peppers, cucumbers (which were very bitter at the time), and other vegetables.

Meat, as in other ancient cultures, did not appear on the Greek table every day, and its main sources were sheep and goats, which were raised in abundance. They were often used as sacrificial animals, and after the sacrifice, they were eaten at specially organized feasts. Beef was rarely eaten; only the wealthy could afford it. Pork was not very popular. Among poultry, chicken was often prepared, and of course, they ate chicken eggs. They hunted boars and deer, as well as various birds, including small birds. However, near cities, large animals were not found, so games rarely appeared on the table. Cheeses made from sheep, goat, and cow milk were also common products.

If in ancient times the aristocracy disdained eating fish—as mentioned in Homer’s poems—in archaic and classical Greece, all sea products were consumed. Tuna and sturgeon, caught in the mouths of major rivers of the Black Sea, were especially valued. Fish was salted and dried; crabs, lobsters, octopuses, cuttlefish, and so on were also eaten.

Mollusks, primarily oysters and mussels, were consumed in large quantities.

The Greeks ate fruits like apples, pears, figs, and grapes. For dessert, they had dried figs, raisins, and honey, which was also added to salads and bread.

They drank water, milk (often goat milk), and wine. Beer was known but not particularly popular.

Did They Really Believe That Thunder and Lightning Were Zeus’s Anger, and That a Three-Headed Dog Awaited Them Underground?

Some did, and some didn’t. Since ancient times, myths have explained the world’s structure, and most Greeks certainly did not question them: they saw the gods’ will behind natural phenomena, with Zeus throwing lightning bolts and Poseidon controlling the waves. However, with the development of philosophy and science, by the 6th century BCE, educated Greeks began to doubt such a worldview. On one hand, the world of gods seemed insufficiently structured and logical; on the other, the concept of Hades, where everyone became bodiless, memoryless shadows, seemed hopeless.

In some new philosophical ideas, powerful elements took on the primary role, while in others, the gods were absent altogether. Nevertheless, intellectual musings about the world’s structure were typical of a narrow educated stratum, while more ordinary people continued to believe in omnipotent gods, mighty heroes, and fearsome monsters. They accepted these stories as a given but worshiped the gods more out of tradition than genuine faith.

How Much Larger Was the Poor Population Compared to the Rich, and What Were the Relations Between Them?

We do not know the exact ratio of wealthy to poor populations in Ancient Greece, as it varied greatly from city to city and era to era. Even in cities like Athens and Sparta, these figures are very approximate. In Athens in the 5th century BCE, there were about 300,000 people. Among them were around 40,000 free men, which is about 10–15%. Adding their family members brings the number to roughly 150,000 people. Around 100,000 were slaves, and the rest were free non-citizens, known as metics. Slaves were not just poor; they had no property at all.

The Solonian reforms of the 6th century BCE divided the free citizens of Athens into four property classes. The wealthiest, whose annual income exceeded 26,000 liters of grain, wine, or oil, were called pentacosiomedimnoi (500-medimnoi). Such a Greek could own large lands and gardens and possibly even his own ships. In the case of war, they were required to equip a warship at their own expense. Those whose income ranged from 300 to 500 medimnoi were called hippeis, or horsemen, meaning they could afford to maintain a horse.

In Greece, where fertile land was scarce, this required either a piece of uncultivated land or purchased feed, which was quite expensive. These citizens owned substantial land and spacious, wealthy homes. During wartime, they naturally served in the cavalry.

Citizens with an income between 200 and 300 medimnoi were called zeugitai. These were sturdy landowners who could maintain a normal household and had enough land to do so. These citizens formed the backbone of Greek city-states and initially constituted the majority. During wars, they served as heavy infantry—hoplites, since their income allowed them to buy armor and weapons. Finally, those with even lower income were called thetes. These were people who were barely making ends meet; they were exempted from any duties in the city, as it could undermine their already modest budget.

Essentially, thetes were poor farmers and the working poor. During wartime, they served as lightly armed infantrymen, whose role in battle was minimal, and as rowers in the fleet. Greeks did not use slaves on their galleys; the rowers were poor but free men. Initially, there were relatively few thetes, but gradually the number of poor in large cities increased. From these examples, we see that the wealthiest people were at least two and a half times richer than the poor and about twice as wealthy as the middle class—zeugitai. The gap between the rich and poor in Ancient Greece was smaller than in modern society.

Naturally, poor citizens and free non-citizens did not particularly like the rich, but since any issue could be resolved in court (and for citizens, also in the assembly or other governmental bodies), open conflicts were rare. In some cases, citizens were paid for participating in the assembly, serving in court, or were even given funds to attend the theater during festivals. One could also turn to the authorities for social support. Such measures prevented social explosions.

The situation of slaves varied in Greek states, and there were occasional small uprisings. The hardest work in Athens was in the Laurium silver mines, from where slaves would escape at the first opportunity. Moreover, the positions of private slaves and state slaves differed; the latter could serve as policemen, clerks, jailers, heralds, and so on. In fact, they were state employees and were in a better position than other slaves. In Athens, where slaves were treated fairly decently (which sometimes caused discontent among citizens who considered them too bold), there were no uprisings.

Were the Greeks as Warlike as the Vikings? Did They Often Engage in Warfare?

The Greeks were very good warriors and often fought, but their martial nature was somewhat different from that of the Vikings. Essentially, the Vikings were professional pirates and mercenaries who roamed the world for plunder and profit. They posed a threat even to their own compatriots. Sometimes the Vikings managed to conquer significant territories and even establish kingdoms, but these entities often survived only due to the strength of small military bands that did not exert significant cultural influence on the subjugated people.

The Greeks were good warriors because they knew what they were fighting for and were well-prepared for battle. Ideally, every citizen of a Greek city-state would arm himself at his own expense and, if necessary, join the militia. Usually, such a “militia,” a force of armed citizens, had a good fighting spirit but could not compete on the battlefield with professional soldiers. However, constant physical exercises and competitions made the Greeks strong, accurate, and ready for combat.

Moreover, the Greeks possessed brilliant battle tactics.

They formed in long lines shoulder to shoulder, shielded, approached the enemy at arm’s length, and fought hand-to-hand with short spears and swords. This style of fighting required composure and provided a sense of support from comrades standing closely on either side and behind. To learn to move in a phalanx—this formation was called—a Greek soldier would undergo military training. The best were the Spartans, who almost daily practiced military skills.

Constant military conflicts that arose between Greek states and their neighbors were also important for training. These wars were swift and did not lead to heavy losses. If one phalanx overturned another, the losers would flee, abandoning their shields. Victors could not leave their heavy shields on the ground, as it was considered unworthy of a warrior, and running with them in hand was inconvenient. Therefore, the defeated did not suffer losses during the retreat. Usually, a truce was declared immediately after the battle to bury the dead.

Greek farmers did not like to fight unnecessarily, as it distracted them from farming, but they were always ready for war and well-prepared. This played a huge role in the defeat of such dangerous and experienced warriors as the Persians, who conquered vast territories but were defeated by the small Greek cities.

Did They Invent the Olympic Games?

Yes, there is no doubt about it. The Greeks had a tradition of holding competitions in honor of the gods, as it was believed that the gods took pleasure in the process of choosing a winner (naturally, only their chosen one could win). The most important competitions were held under the auspices of major sanctuaries at regular intervals. For example, in Athens, there were the Panathenaic Games in honor of Athena, in Corinth, the Isthmian Games in honor of Poseidon, and in Delphi, the Pythian Games in honor of Apollo. However, the most prestigious and significant were the Olympic Games, held at the sanctuary of Zeus in Olympia, on the Peloponnesian Peninsula.

According to Aristotle, the first games took place in 776 BC, although this might be a legend. The Olympic Games were held every four years. To ensure that athletes could travel to Olympia and return home without fear for their lives and freedom, a pan-Hellenic truce was declared during the games. Initially, the only event was a running race, but gradually, other sports were added. Victory in these competitions was highly honorable and glorified not only the athlete, known as an Olympian, but also their city. The games continued until the end of the 4th century AD when they were banned along with other pagan festivals.

In modern times, some European competitions were traditionally called the Olympic Games, and since 1896, the games were revived and, like before, began to be held every four years.

Why Is Everything Ancient Still Considered the Most Beautiful by Many?

To answer this question, one needs to understand what people generally consider beautiful. Scientists suggest that the sense of beauty is partly explained by biological reasons. For example, people like the division of an object along its length in a ratio of 68 to 32%, which is called the golden ratio. On the other hand, something is considered beautiful if it is associated with the cultural tradition of a particular people.

Ancient Greek sculptors, artists, and architects were known for their high artistic sensibility and often intuitively found proportions pleasing to the human eye. They placed great importance on accurately copying human anatomy while maintaining strict symmetry in the depiction of the face and body, which corresponds to beauty standards accepted in various cultures.

However, the most significant reason is that Greek art, slightly modified by the Romans, became the foundation for the art of several European peoples. In the Middle Ages, much changed, but during the Renaissance, artists returned to Antiquity, actively using ancient images, and sometimes copying works of art. From this period, classical education, which included the study of Ancient Greek and Latin, as well as acquaintance with ancient art, began to develop. From the 18th century, this became standard, and Ancient Greek art was considered the ideal and foundation of European art. Despite the significant changes in art today, the ancient foundations of European culture are well-known, continue to influence modern culture, and, because of this, ancient art seems beautiful to many.

Why Did Greece, With All Its Advantages, Not Become a Great Empire Like Rome?

The Greeks were prevented from establishing a large empire by the very structure of their society. The ancient Greeks lived in independent city-states—poleis, which usually controlled nearby, easily visible lands. Colonies founded in distant lands usually immediately became independent states, maintaining friendly relations with their metropolises but remaining independent from them. To address various issues, such as waging war against a common enemy, the poleis formed alliances: some lasted for centuries, while others existed briefly.

If one city gained strength, a coalition of opponents would immediately form against it, attempting to weaken the neighbor. Some states, particularly Athens and Sparta, managed to control fairly large territories by Greek standards, but they extended their influence mainly through allied relations. The Roman state, however, was essentially the rule of one city that managed to subjugate vast territories.

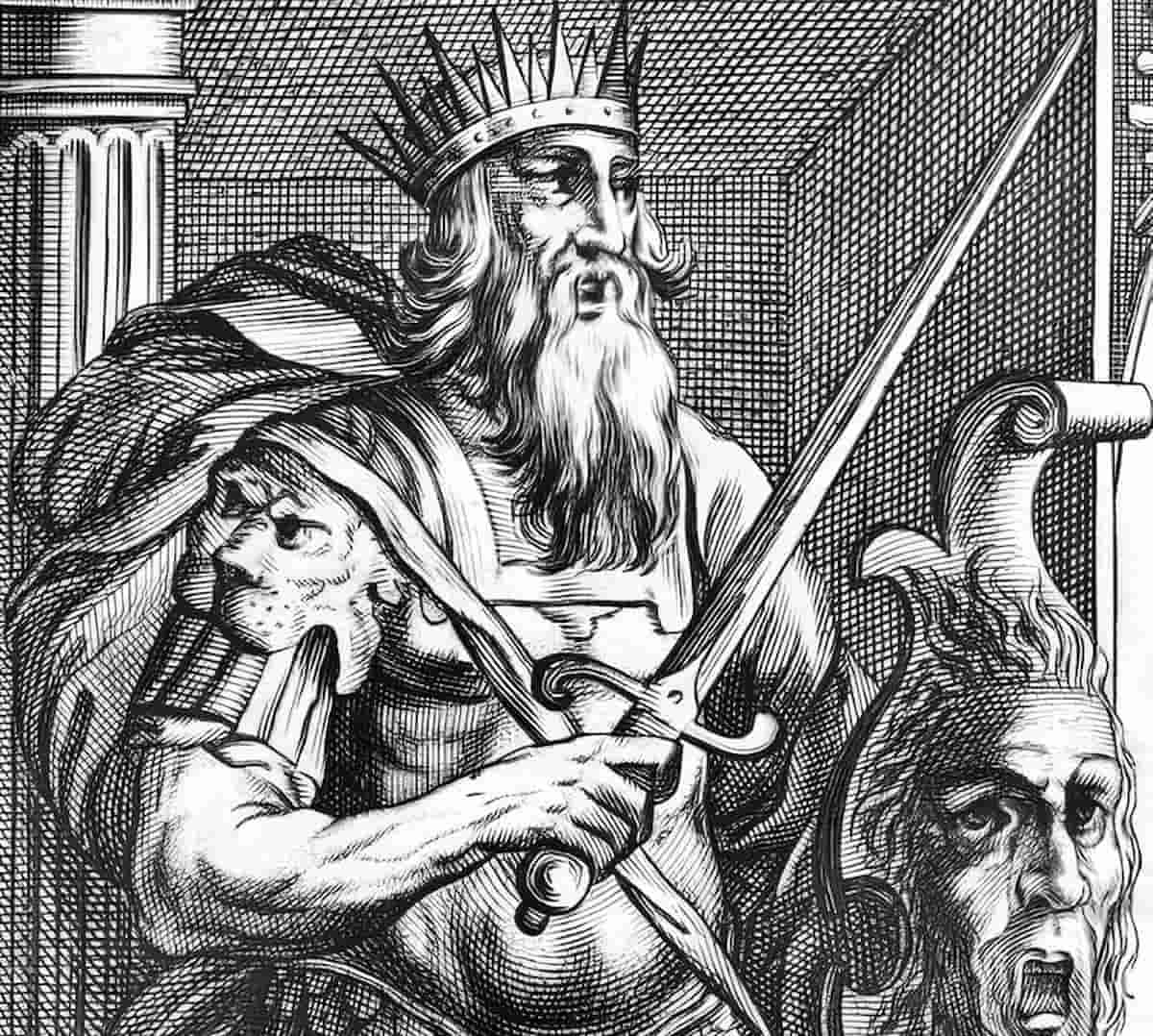

The Greeks managed to establish a large state only under the Macedonians—a people possibly related to them but considered barbarians. Under the unified rule of King Philip II, the Macedonians conquered and effectively united Greece, and then, thanks to the exceptional military talent of his son, Alexander III, known as the Great, they defeated the Persian Empire and conquered some of its neighboring territories.

Despite the leading role of the Macedonians, the Greeks played a huge role in this conquest, and their language and culture became unifying forces for the conquered territories. However, this state barely outlived its founder, but on its ruins emerged large Greek states: the Ptolemaic Egypt, the Seleucid Empire, and the Kingdom of Pergamon. Gradually, the Romans subjugated most of these states.

How Did Such a Vast Civilization Disappear?

The Greek civilization did not disappear like the states of the American Maya or the mythical Atlantis. The Romans, who conquered Greek territories, treated Greek culture with respect, recognizing the taste and education of the Greeks, and they preserved local self-government in the cities, allowing the ancient traditions to be maintained and developed. Thus, Greek culture did not disappear but continued to develop within the Roman state. After the Roman Empire split into the Western and Eastern Empires, the Byzantine Empire gradually formed in the latter’s territory, with the Greek population at its core, speaking Middle Greek—a later form of Ancient Greek.

From the end of the 7th century AD, it became the official language of the empire. Of course, Orthodoxy became the main religion of Byzantium, but its culture was inherited from the ancient Greeks and Romans. The Greeks did not lose their cultural uniqueness even under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, preserving it until the early 19th century, when Greek statehood was revived. Therefore, modern Greece is a rightful cultural successor of the ancient Greek states, with which it is connected by an unbroken line of historical development. Ancient Greece did not perish but transformed into modern Greece.