Throughout the years, Christian Spaniards fought Muslim invaders to reclaim their homeland, an effort known as the Reconquista or Reconquest. The Moors of North Africa did indeed enter Visigothic Spain in the eighth century and eventually take control of much of the peninsula. Some Christian strongholds held out in the north’s mountains, and they were among the first to take up weapons and begin expanding their frontiers southward. These protected areas probably helped the Christians maintain a veneer of authority over the ancient Visigothic realm. Granada was finally captured by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492, marking the end of the Reconquista. The artistic, political, and social landscapes of Spain were irrevocably altered by this lengthy period in the country’s history. The year 1492 was significant because it marked the end of the Middle Ages as well as the year when the Americas were discovered.

Moorish invasion at the origin of the Reconquista

The Visigoths, a Germanic group, have held the Iberian Peninsula continuously since the fifth century. They first came to the peninsula to serve Emperor Honorius, who had them expel the Vandals, Alans, and Suebi from the area (412). However, until Clovis succeeded in 507 in driving them out, Aquitaine remained the core of their power. In 554, the Visigoths relocated their capital to Toledo, Spain. However, the Visigoths endured succession difficulties and a certain economic downturn when they unified the realm and established Catholicism, paving the way for the Muslim invasion. Tarik, a Berber officer, led an army over the Strait of Gibraltar and defeated the last Visigoth monarch, Rodrigue, in 711. Within a short time, the Muslim conquest of the peninsula was complete, with the exception of the northern mountainous areas (the Cantabrian Mountains and the western Pyrenees).

Christian resistance and the beginning of the Reconquista

Around the year 722, Pelagius, a descendant of the Visigoth rulers, established a kingdom in Asturias and took up weapons in what was considered the first recorded instance of resistance. When the dust settled at Cavadonga, the Moors had been soundly defeated. This first Christian triumph marks the beginning of the Reconquista. The Muslim empire continued to expand despite the incident. Umayyad (an Arab dynasty of caliphs ruling the Muslim world from 661 to 750) leader Abd al-Rahman declared himself Amir of Córdoba and severed ties with the Caliphate of Damascus in 756. The Emirate of Córdoba did not become a caliphate until 929, when Abd-el Rahman III declared it to be one. Intellectual and artistic growth accompanied economic growth in the area during this time.

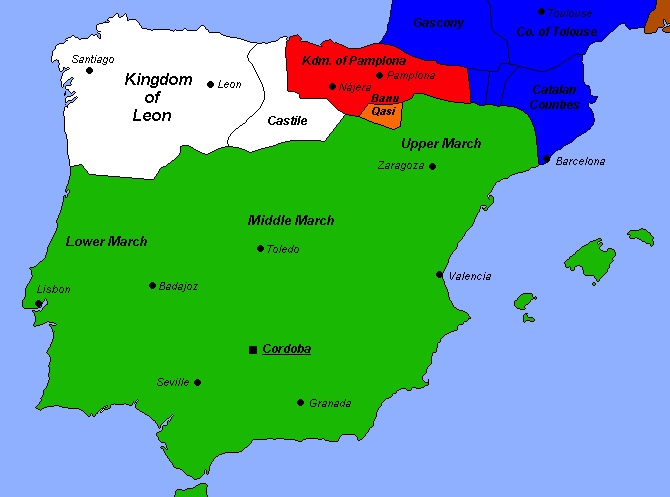

Christians started making their way down from the highlands. Alfonso, the son-in-law of Pelagius, took control of a large portion of Galicia and León. Under King Alfonso III (r. 866-910), the kingdom of Asturias expanded its boundaries to the Duero River and relocated its capital from Oviedo to León. In the event of his passing, his sons would divide the property equally. Other kingdoms, like Navarre’s, emerged elsewhere as a result of Christian opposition, such as in the year 830. All of these regions were united by Sancho the Great, King of Navarre (1000-1035), and then were once again split among his sons via the process of succession. León, Navarre, Castile, and Aragon were the Christian kingdoms of the time. When Christians in Spain were at odds with one another, they were no match for the Moors. Kingdoms did go to war with one another, and some monarchs even allied with the Muslims to protect their own power.

Reconquista of the Spanish Peninsula

At the start of the 11th century, the roles began to switch. Smaller autonomous Moorish states, known as “Taifa kingdoms,” replaced the Caliphate of Córdoba. Due to the decline of the Moors’ supremacy and the rise of Ferdinand I’s Castilian kingdom after its conquest of León in 1037, the stage was set for the eventual Christian conquest of the region. Especially considering how the Christianization of the rest of Europe and the backing of the pope and foreign nobles were both facilitated by the pilgrimage to Compostela. To this end, in 1085, Alfonso VI, king of Castile, led an invasion against the Moors and captured Toledo with the help of some French knights. Muslim kings from the Taifa kingdoms appealed to the Almoravids, a Berber dynasty in North Africa, for assistance in the face of the enormity of the invasion. Both of Alfonso VI’s big setbacks in 1086 and 1108 may be traced to the latter’s involvement. These new conquerors, however, cared little about the Christian kingdoms and were more interested in unifying the lands under Muslim dominion.

Following the fall of Valencia in 1094 at the hands of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (also known as the El Cid), the Christian Reconquest did not gain new momentum until 1118, when King Alfonso I of Aragon, known as the Battler, fought more battles against the Moors and ultimately captured Zaragoza, which he promptly made his capital. The Almoravid dynasty of North Africa was deposed by the Almohads about the middle of the 12th century. As a result, the reformed Muslims eventually came to dominate the former Moorish regions of Spain. Conflicts with Christian communities arose rapidly. The worst of them occurred in 1195 at Alarcos, when the Castilian king, Alfonso VIII, was soundly defeated. The Christian community, however, benefited because they finally chose to band together to fight the Muslim invaders. The brilliant victory at Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 may be attributed in large part to this alliance and the encouragement of the powerful Pope Innocent III. The following years were distinguished by the conquest of Córdoba, Valencia, and Seville and the collapse of the Almohad authority. Only the kingdom of Granada was under Muslim occupation by the end of the 13th century.

Christian Spain was rebuilt

Never truly united during the Reconquista, Christian Spain at the end of the 13th century was gradually built up. When Portugal declared its independence from León in 1139, it severed ties with Spain. Following the Reconquista, Castile and Aragon remained the two greatest kingdoms. The social strata were irrevocably altered by the long process of reconquest that lasted many centuries. The Spanish aristocracy was tolerant, warlike, and desperate for independence; the dynamic clergy believed that the defense of religion through violence was a necessity; and a group of small landowners, to whom the rulers had granted fueros, guarantees, and benefits offered to facilitate repopulation, would fiercely defend their rights. Muslim and Jewish people were not driven out of the area and instead lived side by side with Christians. Living together like this promoted communication across different cultures. It’s true that, thanks to translation efforts on both sides, the world’s greatest literature and ideas are now more widely read and understood. Examples include some of Aristotle’s and Averroes’s writings.

The end of the Reconquista in 1492 with the capture of Granada

Up until the 14th century, however, the peninsula was plagued by internal instability due to a series of succession crises and disagreements between the royal family and the nobility. After decades of Reconquest, Spain was indeed politically divided, and it wasn’t until Ferdinand V of Aragon married Isabella of Castile in 1469 that the nation was able to unite under a single monarchy. The capture of Granada in 1492 marked the formal end of Muslim authority over the peninsula, which had been gradually eroded through a process of political and spiritual unity. There were intermittent conflicts in Spain for seven centuries, and each one left a lasting mark. Both the length of time the Reconquista lasted and the intermittent nature of the combat that characterized it may be traced back to the disintegration of Christian nations into kingdoms that occasionally fought war against one another. By the 12th century, a crusade against the Muslim population had developed into the Reconquista. The Reconquista ended in the 15th century, when Catholic Kings had successfully promoted national religious unity around Catholicism and had united the kingdom politically.

IMPORTANT DATES OF THE RECONQUISTA

July 711: The Muslims conquer Spain

The last Visigoth king, Rodrigue, was defeated on the Rio Barbate (Battle of Guadalete) by a Berber military expedition led by the lieutenant Tarik. Musa ibn Nusayr, an Arab ruler, had ordered his men to cross the Straits of Gibraltar in order to conquer Spain. The Visigothic kingdom was utterly annihilated as a result of their brilliant attack. In fact, the majority of the peninsula quickly submitted to Islamic authority. North of the equator, just a few of fortified mountain peaks held out.

722: The Battle of Covadonga launches the Reconquista

Pelagio, also known as Pelayo, a descendant of the Visigoth rulers, rallied the people of Asturias to fight against the Moors. In anticipation of a battle with the Berber forces who had been sent to put down the uprising, Pelagius had made his way to the front lines. The militants emerge victorious from the clash at Covadonga. The Spanish Reconquista was sparked by this event, which represented a glimmer of hope for Christians living under Muslim rule.

May 15, 756: Foundation of the Emirate of Córdoba

The Emirate of Córdoba was established when Abd al-Rahman, a member of the Umayyad dynasty, took authority in the city and declared himself emir. My government in Iraq under Abd al-Rahman was a model for the world. Under Abd al-Rahman III’s caliphate, the Emirate of Córdoba flourished as a major intellectual and cultural hub for Muslims. This was in 929. Nevertheless, the northern mountainous areas kept their Christian faith.

1031: End of the Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba was thrown into a deep social crisis due to the religious intolerance of Caliph al-Mansur, also known as Almanzor (981-1002). All the different branches of Islam in Spain had really convened for a war. The caliphate was permanently fragmented into smaller territories, known as Taifa kingdoms, in 1031.

1037: Castile expands

King Ferdinand I of Castile (1035–1065) set out to conquer León and incorporate its territories into Castile. Moreover, he murdered his own brother, Garcia IV, in order to gain the province of Navarre in 1054. In 1064, he defeated the Moors and took control of Coimbra, establishing Castile as a major world power.

May 25, 1085: Capture of Toledo by Alfonso VI

Toledo, a kingdom under Moorish authority since 711, was conquered by King Alfonso VI of León and Castile. Castile became very strong after Ferdinand I’s conquest of León in 1037, which allowed it to launch the Reconquista. Unfortunately for Alfonso VI, the Almoravids, who had arrived as reinforcements, defeated him twice, in 1086 and 1109.

October 23, 1086: Defeat of Alfonso VI against the Almoravids

The Muslim rulers of the Taifa kingdoms, alarmed by the prospect of the monarch of Castile’s march, appealed for assistance to the Almoravids, a Berber dynasty based in North Africa. The conflict at Sagrajas led to Alfonso VI’s eventual downfall. The latter were defeated once again in 1108. This time it was at Uclès.

1094: The Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar takes Valencia

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, also known as the El Cid, was a vassal of King Alfonso VI of Castile who conquered the Muslim-ruled kingdom of Valencia. Until his death in 1099, he served as its governor. Up until 1102 AD, the kingdom held out against the Almoravids. However, it eventually came back under Moorish control.

1118: Capture of Saragossa by Alfonso I, the Battler

Alfonso I, often known as “the Battler,” king of Aragon and Navarre, captured Saragossa with the aid of French nobles at the crux of the Reconquista. He fought the Moors for a total of four years before finally defeating them. His moniker originated from all the fights he’s been in. Zaragoza became the Aragonese capital under Alfonso I. At the time of his death in 1134, the territories of Aragon and Catalonia were unified into a single kingdom.

1139: Portugal established as a kingdom

After his victory against the Muslims at Ourique, Alfonso I, the Conqueror, elevated himself to the position of king of Portugal. He made a public proclamation of his freedom from the Leonese monarchy.

July 19, 1195: Christian defeat at Alarcos

As the Christian monarchs of Spain expanded their empire, the Almohads defeated the Almoravids and established themselves in North Africa. Soon after, the new Muslim monarchy intervened in Spain and, led by Yakoub el-Mansour, dealt Alfonso VIII of Castile a crushing defeat in the Battle of Alarcos. Following the incident, Christian communities began working together to counter the Muslims. After being encouraged by Pope Innocent III, the reconquest turned into a genuine crusade. In 1212, it resulted in the decisive victory at Las Navas de Tolosa.

July 16, 1212: Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa

With the help of their rulers Sancho VII of Navarre, Peter II of Aragon, and Alfonso VIII of Castile, the Christians of Spain were able to vanquish the Almohad Muslims in Andalusia. Over the course of the conflict, about 60,000 Arab troops were killed. This spectacular victory was a major step forward for the Catholics in their effort to retake the Muslim-occupied territory of Spain. The defeat of the Arabs in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa was the beginning of the end for the Almohad dynasty in Spain.

1236: Córdoba falls to the Christians

Crowned King of Castile and León, Ferdinand III took control of Córdoba. He conquered Seville in 1248 and ruled the city for the next century.

1238: The Christians took the kingdom of Valencia

James the Conqueror defeated the Muslims and conquered their kingdom of Valencia. He had already conquered the Balearic Islands three years previously.

September 23, 1343: Death of Philip III of Navarre

Philippe III of Navarre was the grandson of King Philippe III of France, making him not only the count of Evreux but also a “prince of French royal blood.” Navarre’s king consort when his cousin Charles IV the Fair died in 1328. Alfonso XI, King of Castile, enlisted him to fight with his forces in the Reconquista and the Hundred Years’ War against the English. He was killed by an arrow to the neck at the siege of Algeciras in the Granada kingdom.

1478: Sixtus IV authorizes the appointment of Spanish inquisitors

King Ferdinand V of Spain and his Catholic wife, Isabella the Catholic, were given permission by Pope Sixtus IV to create a monarchically-controlled Inquisition in their kingdom. The Marranos (converted Jews) were sought out and condemned after the Reconquista because they secretly practiced Jewish rites. The persecution of Jews in Spain dates back to 1492.

January 2, 1492: End of the Moorish Kingdom of Granada

The final Muslim bastion in Spain, the kingdom of Granada, was conquered by the Catholic Monarchs. Muslim rule in Spain came to an end with Sultan Boabdil’s (Muhammad XII of Granada) resignation, which had lasted for seven centuries. The city was visited by Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. This victory put an end to the “Reconquista,” a series of conflicts fought against the Muslims during the seventh century. The country’s new boundaries delineated an united Spain. After the month of March, everyone was on the same page because of their faith. The Queen of Spain banished all of the Jews from the country after the Muslims did so.

Bibliography:

- García-Sanjuán, Alejandro. “Rejecting al-Andalus, exalting the Reconquista: historical memory in contemporary Spain.” Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 10.1 (2018): 127–145. online

- Hillgarth, J. N. (2009). The Visigoths in History and Legend. Toronto: Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1993). The Medieval Spains. Cambridge Medieval Textbooks. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39741-3.

- Collins, Roger (1989). The Arab Conquest of Spain, 710–797. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-15923-1.