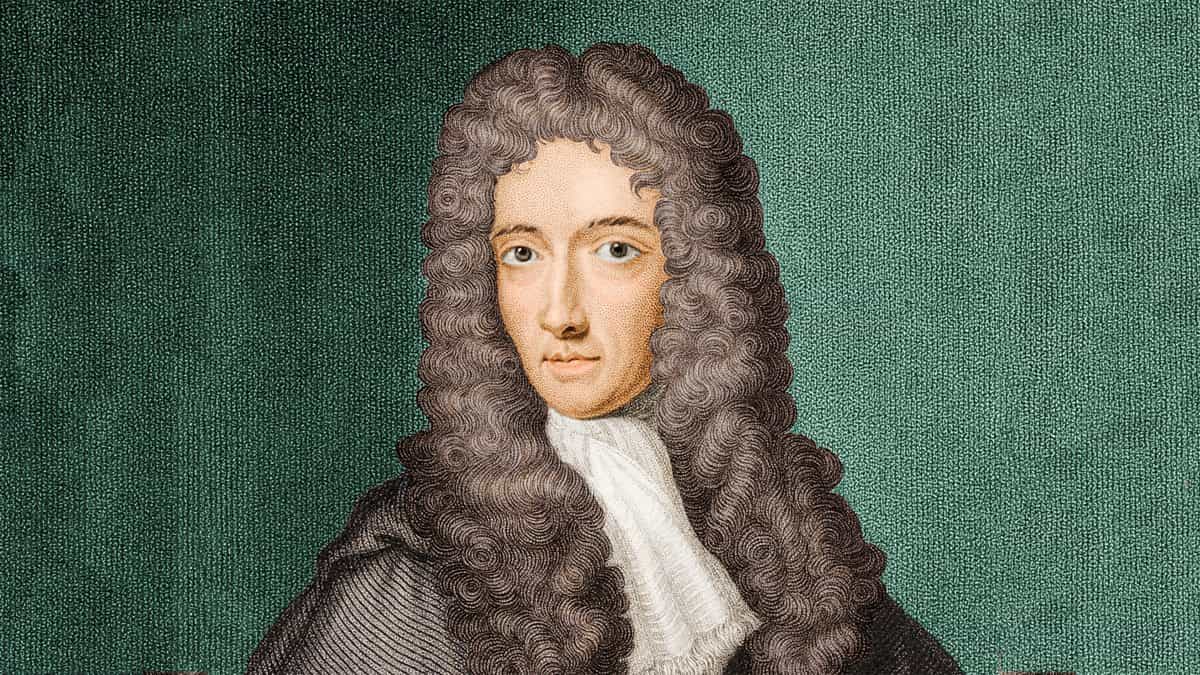

For Robert Boyle, the experiments were always at the center of his life. He discovered the potential of scientific research first while living in the mansion inherited from his father, Richard Boyle, the Earl of Cork, in Stalbridge, Dorset, and decided to devote his life to science. He enjoyed the privileged care and education offered to him until that time. He traveled to Europe and wrote on morality. He lived at the house in Pall Mall, London, with his famous sister, Lady Ranelagh, from 1688 until his death in 1691. Boyle continued his experimental essays almost daily, and these experiments had always been at the heart of his life.

Who was Robert Boyle?

But most important of all were the experiments he carried out while living in Oxford between 1655 and 1668. He conducted his famous series of experiments at the time, which became the subject of his first scientific book, “New Experiments Physico-Mechanical: Touching the Spring of the Air and Its Effects,” published in 1660. Boyle opened up new horizons with this book by determining the characteristics and functions of air, including its role in breathing, using an air pump or an essential part of the apparatus designed by his then-assistant Robert Hooke, the vacuum chamber. In the second book, which came out in 1662, he wrote the first version of Boyle’s law, which says that vacuums exist in nature and that the pressure of air is opposite to its volume.

Robert Boyle continued to publish books until his death and presented his groundbreaking experimental studies about the nature of color, cold, and countless other subjects. Boyle did a lot of chemical experiments that were based on how practical chemists of his time analyzed and worked with chemicals.

Robert Boyle was an unprecedented pioneer in designing and setting up controlled experiments while carefully recording them. Also, his deep reflection on the nature of experimental investigation led him to create an experimental philosophy. His success in this field is the most significant factor determining his importance in the field of science. His exemplary personality was a more relevant reason for being supported by the newly founded Royal Society, of which he was one of the first members.

Particle philosophy and challenges

Boyle’s experiments have also served a purpose beyond the main facts they have brought to light, and have been used to prove the correctness of the mechanical philosophy, which defends the view that everything in the world can be explained by the interaction of matter and motion. In his own words, “Nor can we conceive of any principles more primary than matter and motion.”

Actually, Boyle did not create this doctrine; his pioneers were thinkers like Pierre Gassendi and René Descartes. However, he has done more than anyone else to transform the idea from a brilliant hypothesis into a doctrine with a plausible experimental basis. One of the most important experiments done by him was the redintegration of saltpetre (a potassium nitrate mineral) from its components, as explained in Certain Physiological Essays in 1661.

From 1666 to 1667, he published The Origin of Forms and Qualities, which was equally influential. He demonstrated that the explanatory principles of the theory of matter inherited from Aristotle, considered valid for centuries, were at worst meaningless and at best unnecessary. In fact, the mechanical or “particle” hypothesis, as he prefers to call it, could better explain everything.

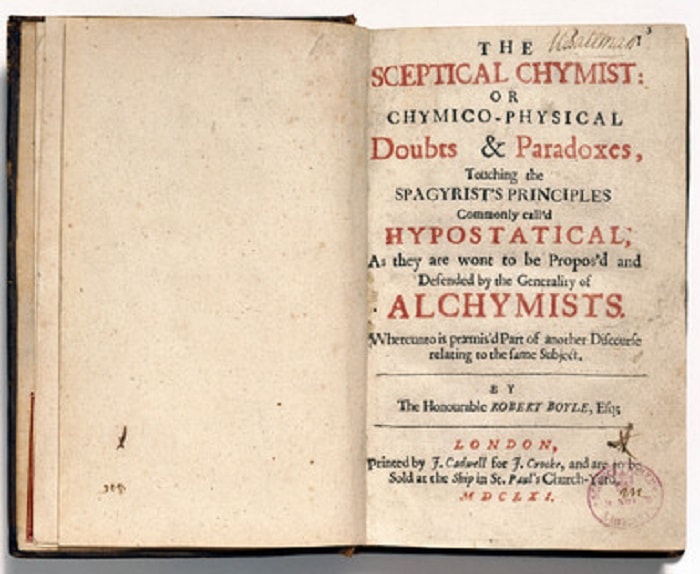

Robert Boyle and alchemy

In this way, Robert Boyle offered a more refined version of mechanical philosophy than his predecessors. He did not only evaluate the size, shape, and motion of the particles of matter but also the distinctive features of the objects they created. His thoughts on such subjects had a significant impact on both Isaac Newton and John Locke. Robert Boyle was sure that mechanical explanations should be used wherever possible, but his mechanical philosophy was not too simplified. He did not see any problem in admitting that there were “subordinate causes,” such as the idea of “flexibility” in the air, under the “most general causes of things.” He was also open to the idea that “corpuscles” of matter could have chemical qualities (not purely mechanical), and even the universe could have “cosmic qualities” transcending the purely mechanical laws. He also took up the idea of transforming basic metals into gold and making strong medicines by processing chemicals.

In his book The Sceptical Chymist from 1661, he clearly expressed his respect for the “true masters,” even though his views were criticized by the inferior alchemists that Boyle found as flawed as Aristotle’s ideas. He tried to learn about the alchemical mysteries for the most part of his life, believing that they could contribute to understanding the functioning of the Earth. He even conducted public alchemy research and published several of its results.

Robert Boyle’s philosophy of nature and religion

In addition to his contributions to understanding the nature of matter, Boyle was deeply interested in every aspect of the natural world and crafted a highly effective “systematic science” perspective. One of his most popular books, The Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy, published in two parts in 1663 and 1671, follows the influential example of Francis Bacon from the beginning of the century and states that scientific knowledge can be applied to agricultural, industrial, and maritime initiatives, and therefore in every aspect of human life.

Robert Boyle believed that science may ignore its true potential if it only tries to teach man the flow of nature but not how to rule it. The book particularly emphasized the value of scientific findings in the pharmaceutical field. Boyle was closely interested in improving health, and he even wrote a controversial thesis in which he criticized standard treatment practices of his time. However, in the end, he did not publish it because of his desire to avoid provoking the medical profession. His publications in this field were concerned with the use of specific weights to detect tricks in drugs.

Boyle’s writings on the epistemology of science and the relationship between science and religion are also substantial. In addition to his experiments-related writings, he spent a lot of time thinking about the proper relationship between reason and experience, as well as the degree of relative certainty that can be expected in different forms of information. In the second issue, Boyle was trying to show the limits of the human mind in the face of an “all-knowing” God. To understand Boyle, it is necessary to acknowledge that theism had a strong influence on his works throughout his life.

Seeking divine power

Boyle criticized many chemists for their practical engagements and called on them to make a “philosophical explanation” of their experiments.

Boyle’s most popular book is a study of worship rather than scientific work. Today we know more about his spiritual life, which helps a lot to explain his ambitious character. He would spend hours studying his conscience. His experimental work can be seen as the reflection of this heart-searching in the natural world. Under his desire to understand nature, there was a conviction that we would be one step closer to understanding God. In fact, Boyle’s sense of the divine potential of science explains his transition to experimentation around the 1650s.

To some extent, Boyle was concerned with the evidence of a supernatural realm that was beyond the mechanical realm and could neutralize the materialist view. He gave no credibility to any thought and stated that the Earth was created by the coincidental interaction of matter without an intelligent designer in the image of God. He fought against this view in his work, Enquiry into the Vulgarly Received Notion of Nature. To understand Robert Boyle, we have to place his science in the context of his ideas as a whole.

Bibliography:

- Vere Claiborne Chappell (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Locke, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 56.

- Marie Boas, Robert Boyle and Seventeenth-century Chemistry, CUP Archive, 1958, p. 43.

- O’Brien, John J. (1965). “Samuel Hartlib’s influence on Robert Boyle’s scientific development”. Annals of Science. 21 (4): 257–76. doi:10.1080/00033796500200141. ISSN 0003-3790.

- Newton, Isaac (February 1678). Philosophical tract from Mr Isaac Newton. Cambridge University.

- “Fellows of the Royal Society”. London: Royal Society. Archived from the original.

- Scott, Chris (1999). “The diving “Law-ers”: A brief resume of their lives”. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (1). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- Levine, Ira N. (2008). Physical chemistry (6th ed.). Dubuque, IA: McGraw-Hill. p. 12. ISBN 9780072538625.

- MacIntosh, J. J.; Anstey, Peter. “Robert Boyle”. In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Robert Boyle”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- Works by Robert Boyle at Project Gutenberg