From the first and second centuries on, the Roman people practiced various occupations and trades. The sources from these periods provide extensive evidence of the diversity of roles undertaken by men of all social statuses, excluding women. Women, especially those of more humble conditions, were assigned roles primarily related to the care of the home and family, as dictated by tradition.

Roman Women Without a Profession

In the Rome of Emperor Trajan, it appears that the female population of ancient Rome did not engage in any specific occupation outside the home. Women of modest means dedicated themselves to domestic chores within the household. They would occasionally leave to go to the public fountain for water, the garbage dump for waste disposal, or to the baths reserved for them.

Noble and wealthy Roman matrons, attended by crowds of servants, had no domestic obligations and were entirely free to manage their time, whether by going to the baths, taking a stroll, or visiting friends. Roman women who sought to be equal to men in literature, philosophy, the sciences, or law considered it humiliating to engage in professions typically associated with men. Inscriptions from the imperial period indicate that, at most, they practiced jobs where men were deemed less suitable, such as hairdressing (tonstrix, ornatrix), midwifery (obstetrix), or nursing (nutrix).

Despite the efforts of emperors like Claudius, who aimed to involve women in guilds, they remained absent. When wealthy matrons responded to Claudius’ invitations, exchanging their support for naval armament for the ius trium liberorum, they always did so through proxies.

Certainly, it was not the women but their husbands who sought assistance from the public grain supply. In paintings from Herculaneum and Pompeii, women are depicted free from any occupation, walking empty-handed, sometimes accompanied by a child, in squares filled with stalls and shops, dominated by men busy with shopping or work. Life was markedly different for men of all social standings: rising almost at dawn, they hurried, especially if employed, to join their guilds, the forum, or the Senate, which were already open early in the morning.

The Clients

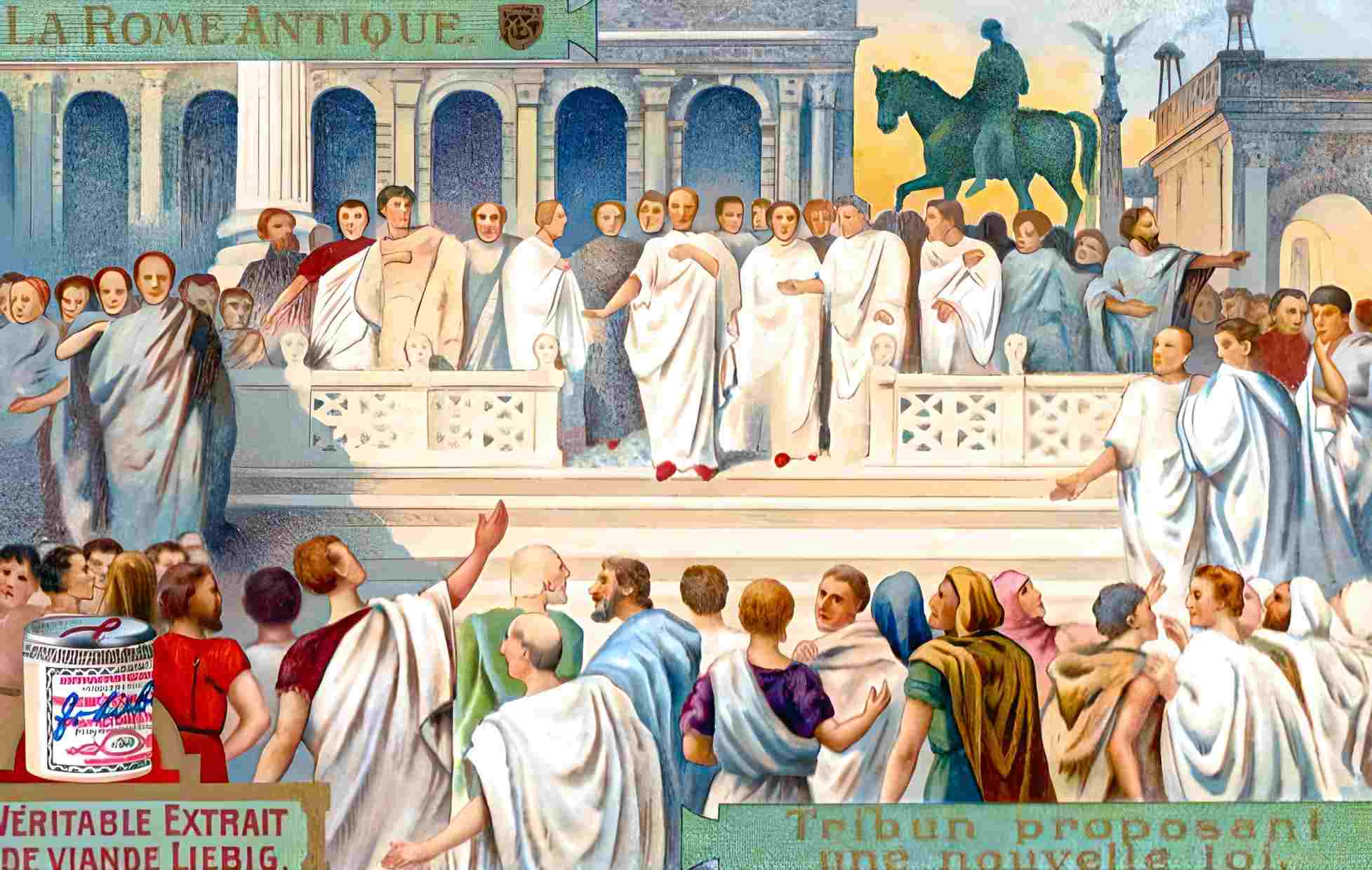

A particular occupation that contributed to income formation was the condition of a cliens (plural clientes), not tied to a specific social class. Ancient Romans, from freedmen to the grand lord, all felt bound by an obligation of respect (obsequium) towards those more powerful than them. The freedman towards the one who had liberated him (the patronus) and on whom he continued to depend, the parasite towards the lord, who (as a patronus) had the obligation to welcome these applicants (the clientes, precisely), assist them in times of need, and sometimes invite them to lunch.

Periodically, the clientes also received a supply of provisions that they carried away in their sportulae (bags) or sums of money when they visited their protector. In the time of Trajan, this practice was so widespread that a tariff, the sportularia, corresponding to six sesterzi per person, had been established for every noble family. Often, the sportula was a resource for survival: lawyers without cases, teachers without students, and artists without commissions presented themselves at the door of the patronus for daily survival.

Even those with a profession added the small income from the sportula to their earnings, and before going to work, even before daybreak, they lined up for the sportula. The importance of a powerful person was measured by the clientele that noisily woke him every morning for the morning salutatio.

The dominus would have lost his reputation if he had not listened to the complaints or requests for help and had not responded to the greetings of the crowd waiting for him since dawn. A strict procedure regulated this daily ritual of the clientele. The cliens could reach the house of the patronus on foot rather than by litter but, obligatorily, had to wear the toga and not dare to call him by name familiarly: the magnate was always addressed as dominus, under the penalty of returning home empty-handed.

The obligation of the toga, a garment of some importance and therefore expensive, posed a difficulty for many. In such cases, the patronus would sometimes be the one to donate it on particular and special occasions, along with the five or six pounds of silver paid annually. The time to receive this gift was not determined by the order of arrival but based on social importance. Thus, the praetors took precedence over the tribunes, the knights over the freeborn, and these, in turn, over the freedmen.

Women did not participate in this daily assistance either as patrons or as clients, except in the case of widows, who requested for themselves what the patronus had done for the now-deceased client. Alternatively, when the client came along on foot or in a litter of wives in distress, presumably unwell, to induce the lord to make more generous donations.

The Rentiers

Far more crucial in terms of the quantity of resources provided compared to these private donations was the public assistance that the Roman state indiscriminately provided to the 150,000 proletarians. These were lifelong unemployed individuals who had the right, until their death, to receive from the annona of Rome, on a specified day of a given month, whatever they needed to survive.

It can be said, as Rostovtzeff suggests, that these individuals also lived on a pension, akin to the large landowners in the provinces whose wealth granted them the right to sit in the Curia with the obligation of residence in Rome. Similarly, those who lived on a pension included the scribes attached to magistrates, occupying a function acquired with money, administrators, and those who had invested capital in the works of contractors. There were also officials who conveyed the commands of central power to the periphery, remunerated by the treasury.

However, Rome was such a vast economic center that it could not sustain itself solely on a policy of assistance and pensions without genuine work and production. Rome, a hub of international terrestrial and maritime commercial activities and a center of consumption for the finest manufacturing production, had to necessarily organize and direct this incessant exploitation.

“The Roman victor already held the entire world; every sea, every land, both hemispheres. And yet, he was not satisfied… For the city, the Syrians and the Numidians wove precious wool, and the Arabian peasant went without bread.”

The Merchants

The intense productive activity in 2nd-century Rome is evidenced by archaeological excavations in Ostia, specifically in the Piazzale delle Corporazioni, featuring a temple at its center dedicated to Annona Augusta, symbolizing the deification of imperial provisioning.

On the inner side of the two-naved porticos surrounding the square, between the columns, 16 small rooms were created. On their thresholds are mosaics symbolically depicting various trade corporations: shipwrights, ropemakers, furriers, timber merchants, weighers, and shipowners, distinguished based on the cities they hailed from, such as Alexandria, Sardinia, Gaul, North Africa, and Asia. Despite the naive and modest depictions, this gives the viewer an idea of the immense scope of economies both near and far in service of the well-being of Rome.

In Rome, hectares of surface were covered by horrea (horreum), warehouses holding various goods, usually accompanied by the tabernae of wholesale merchants.

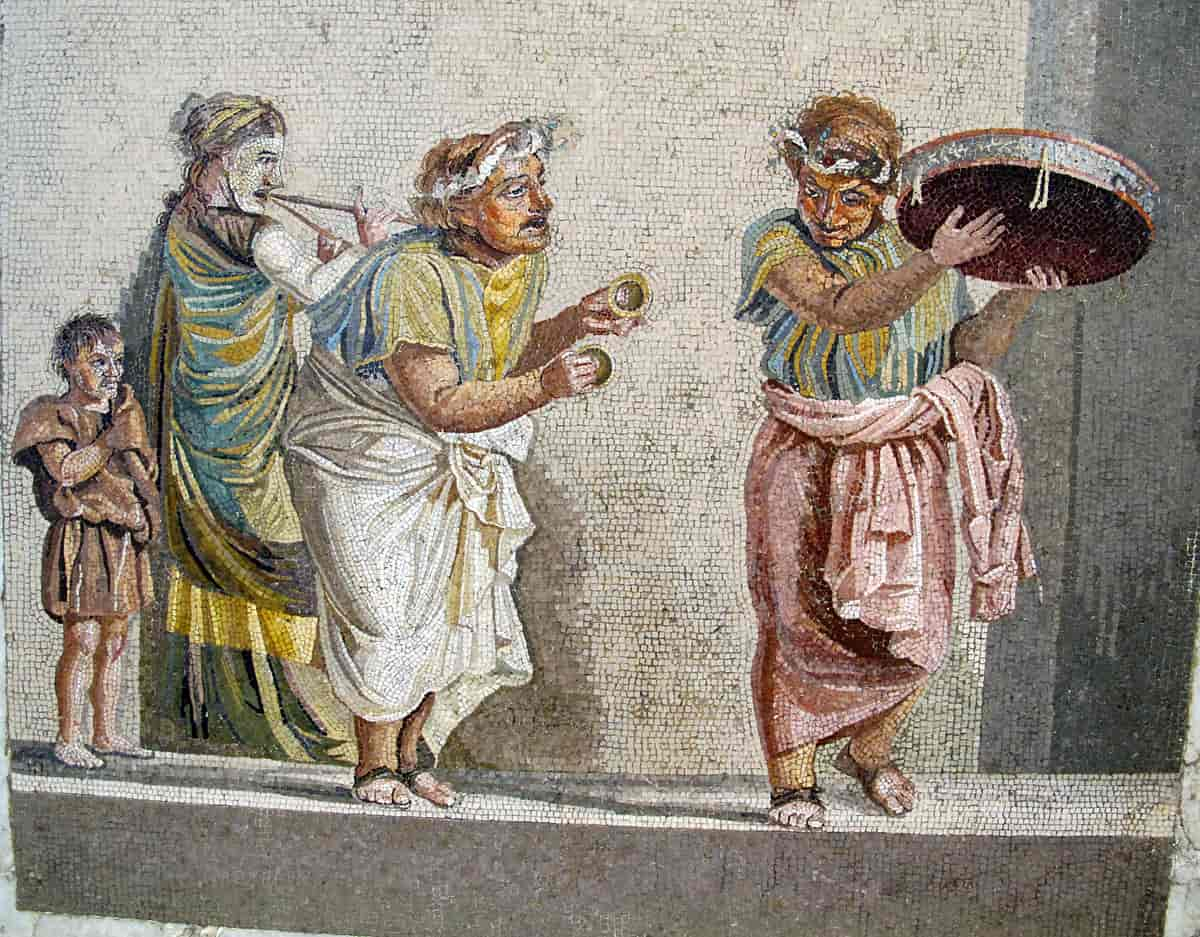

From there, a dense network of workers branched out, including retail merchants, manual laborers necessary for maintaining the warehouse buildings, and workshops of artisans who processed and refined raw materials before they were sold.

To understand how, even in the absence of true productive activities, Rome nevertheless engaged in intense economic activity linked to trade, it is sufficient to consider that there were approximately 150 corporations in Rome. These included wholesale grain, wine, and oil merchants (magnarii), owners of entire fleets of ships (domini navium), engineers (fabri navales), or ship repairers (curatores navium). These corporations bear witness to a broad business turnover involving collaboration between patricians and plebeians, capitalist owners, and wage laborers.

Merchants and Producers

Regarding food commodities in imperial Rome, two commercial categories can be distinguished: those of retail sellers, such as fruit merchants (fructuarii), and those who sell their goods after producing or transforming them, such as the olitores, who were both vegetable gardeners and sellers of legumes, or the bakers who simultaneously practiced the trade of millers.

For the trade in luxury goods, some artisanal processing was always present in the sold goods. Perfumers, craftsmen of the mixtures they sold, goldsmiths producing their jewelry, pearl merchants, or ivory object merchants—the work of skilled artisans who could carve the tusks arriving from Africa. This connection between selling and manufacturing was inseparable for all goods related to clothing, such as those produced by tailors (vestiarii) or shoemakers (sutores).

Manual Laborers

Numerous corporations can be divided into two categories:

- Those that produced what they sold, such as furriers (pelliones), carpenters, and cabinetmakers (citrarii),

- Those that provided labor to the former. The latter included:

- Building corporations, such as those of masons (structores) and carpenters (fabri tignari),

- Transport corporations for land transport, e.g., muleteers (muliones), and those for water transport, e.g., boatmen (lenuncularii), and finally

- Those responsible for the maintenance and supervision of the horrea, the warehouses.

In imperial Rome, there were no industrial districts or factory zones. Workers lived scattered throughout the various areas of Rome, where warehouses and shops, artisan workshops, and houses could be found mixed together. Organized in corporations, Roman workers, regulated by the laws of Augustus and his successors, followed binding rules for everyone practicing the same trade.

In addition to being regulated by lighting hours, the duration of work did not exceed eight hours, except for those whose activities were tied, such as barbers and innkeepers, to the leisure time of their clients. From numerous indications, it can be deduced that the majority of Roman workers stopped working at the sixth or seventh hour in the summer, and certainly between the sixth and seventh hour in winter:

“Into the fifth hour, Rome extends its varied labors;

Martial VI, 8, 3-4

The sixth is rest for the weary, the seventh will be the end.”