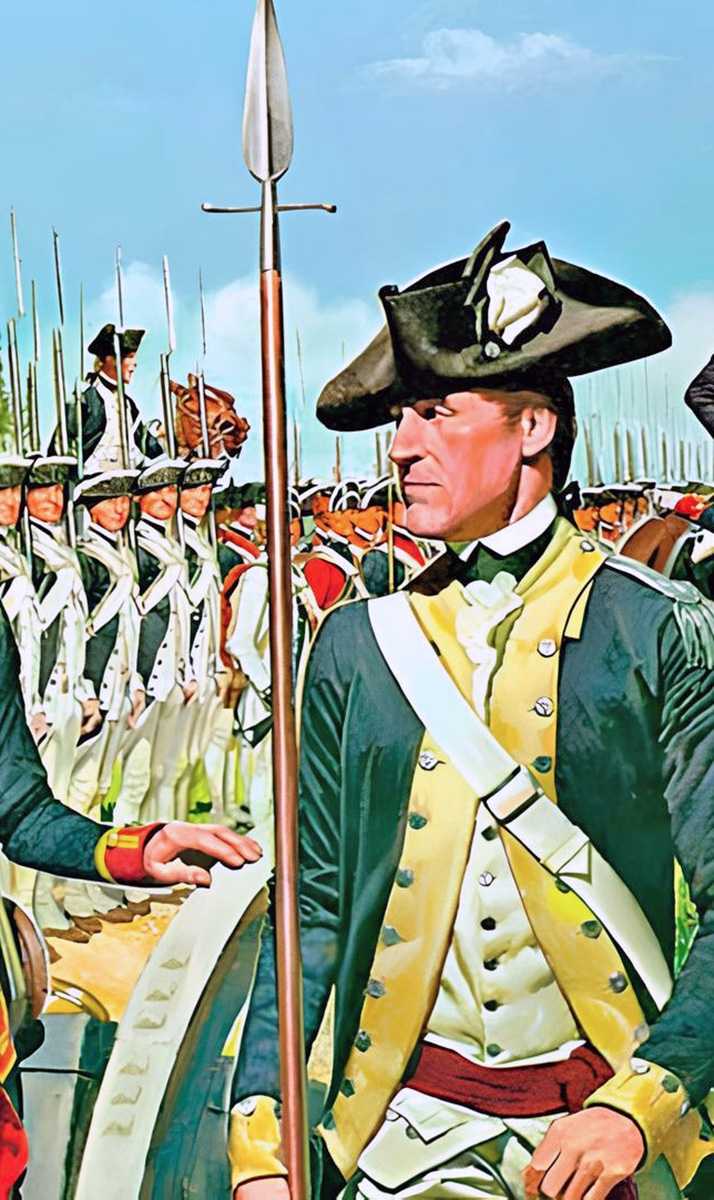

Roman Pilum Spear: An Ancient Javelin with Symbolic Meaning

The Roman pilum, a heavy javelin, was a prominent weapon of ancient Roman legions originating in Celtic culture around the 4th-3rd centuries BC. Characterised by its pyramidal head, the pilum evolved over centuries, altering in size, weight, and design, until it was superseded by other weapons around the 8th century AD.