Roman Society: Social Groups and Their Statuses

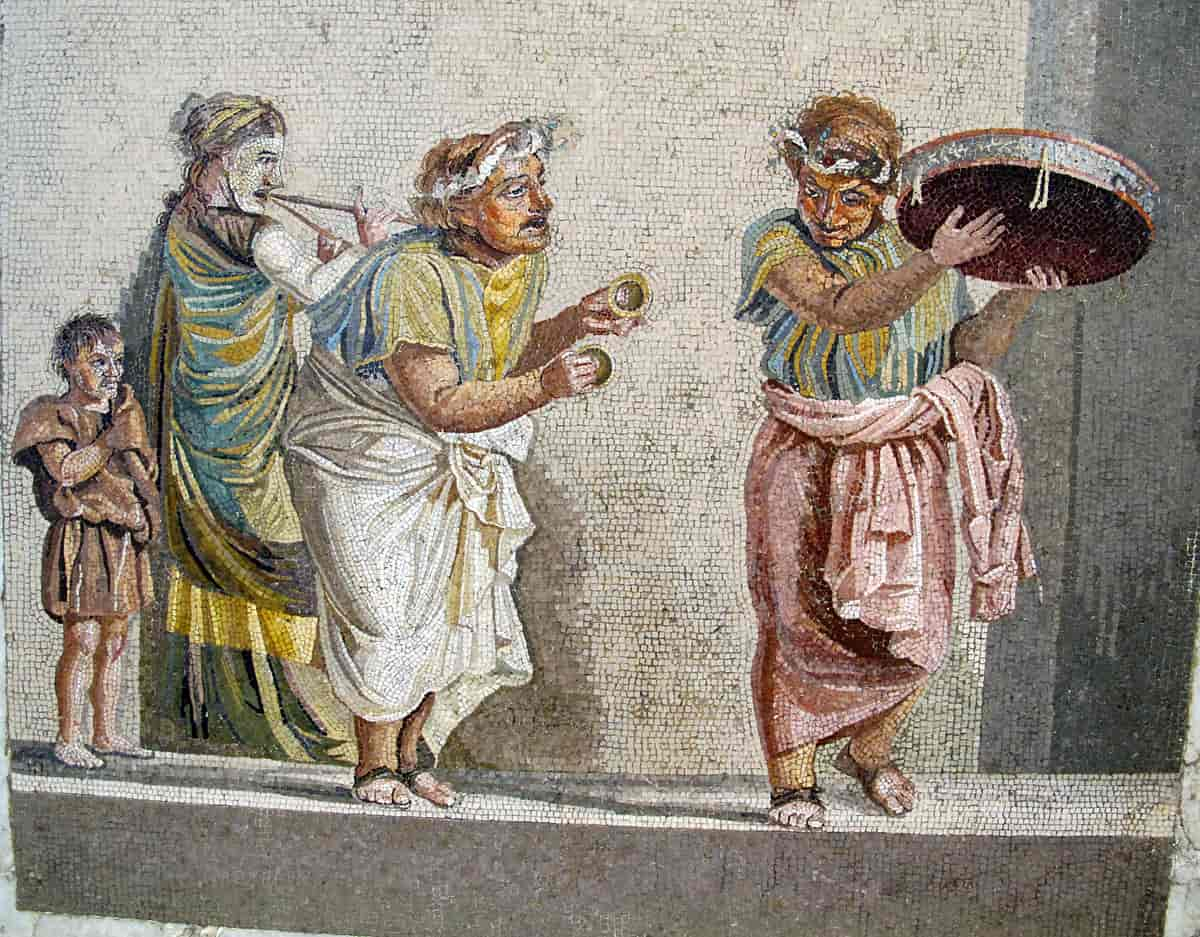

Roman society established the census, a kind of civil status, as early as the 6th century BC. During the Roman monarchy, there were two main classes: the nobles and the people (populus), in addition to slaves and non-citizens.