Rudolf Virchow is a prototypical 19th-century global genius. The scientist was a physician, social politician, and anthropologist, making him a leading figure in his field throughout his day. His groundbreaking studies on somatic cells and disease progression ushered in a new age in medicine, for which he is now best known.

Rudolf Virchow deserves credit for discovering that all human cells originate from preexisting ones through a process called cell division and that cells play a role in illness. What we accept without question now was a radical shift in thinking 150 years ago. By doing so, Virchow established contemporary pathology.

The innovative doctor, however, was not just influential in the research facilities of German academic institutions. He was an advocate for public health on the political front, an archaeologist who worked with Heinrich Schliemann to uncover Troy, and an anthropologist who amassed a remarkable collection of human artifacts. Rudolf Virchow was an all-around scientific genius. But he, too, made some pretty big mistakes every once in a while.

Beginnings of cell theory

The cell is discovered as the basic building block

There are billions of cells in every living person. They may be found in the tissues of the body, including the skin, the blood, the muscles, and the heart. Nowadays, it is assumed that you already know this. On October 13, 1821, in what is now Poland, Rudolf Virchow was born in the town of Schivelbein. At the time, not much was understood about the cellular structure of the body.

Medical practices were changing rapidly during the period, while the natural sciences were thriving. However, the four-juice doctrine, sometimes known as humoral pathology, is still the de facto standard in this field. The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates is credited for conceptualizing this notion, which holds that the human body is comprised not of cells but of fluids such as blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. It’s crucial that these bodily fluids be in equilibrium. It is considered that sickness develops in man if this condition is not met.

Viewing through the microscope

A new generation of scientists, however, is taking a closer look at the human body. The modern, two-stage microscope was invented by British scientist Robert Hooke in the 17th century for the Royal Society in London. These tools have progressed to greater and greater levels of sophistication throughout time. Today, a microscope can increase an image’s magnification by a factor of 400.

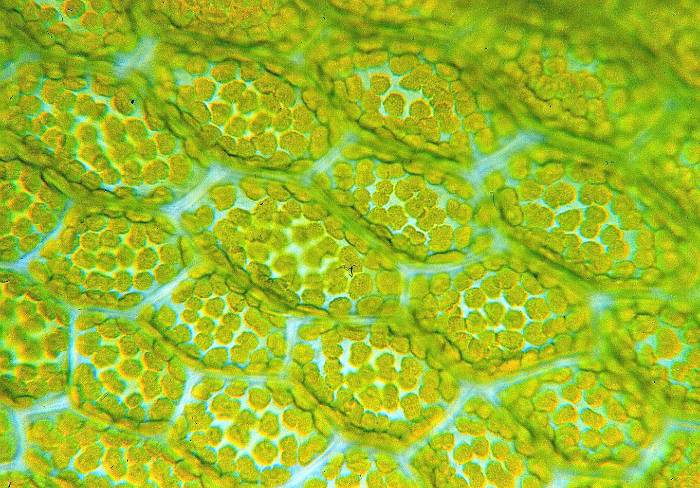

Scientists like Theodor Schwann (a physiologist) and Mathias Schleiden (a botanist) may now examine the anatomy of plants and animals in unprecedented depth. During this period, Virchow first becomes involved in the academic world. An eager young man attends Berlin’s Military Medical Academy on scholarship after learning that his father, a poor merchant, cannot afford to send him to college.

Preparatory work by Schleiden and Schwann

During the time when Virchow, then just 18, was spending his days in the hospital, the anatomists Schleiden and Schwann were digging into the inner workings of plants and animals. All of the research items they’ve been studying seem to have common structural components, they conclude. They team up to write the first generic theory of the cell, which treats cells as the basic building blocks of all known forms of life. Because of this discovery, we may now think of the human body as a network of cells.

Rudolf Virchow likes this updated perspective on the human body. Due to his exceptional academic performance, he was given the opportunity to speak at the Academy’s 50th-anniversary celebration in 1845, when he addressed the “correctness of medicine from the mechanical point of view.” In it, he comes across as a modern, scientifically-minded progressive who doesn’t put much stock in intuitive methods and instead advocates for evidence-based medicine through things like careful observation of patients in hospitals, controlled laboratory settings, and careful analysis of cadaver tissue.

Concentrate on the cellular level

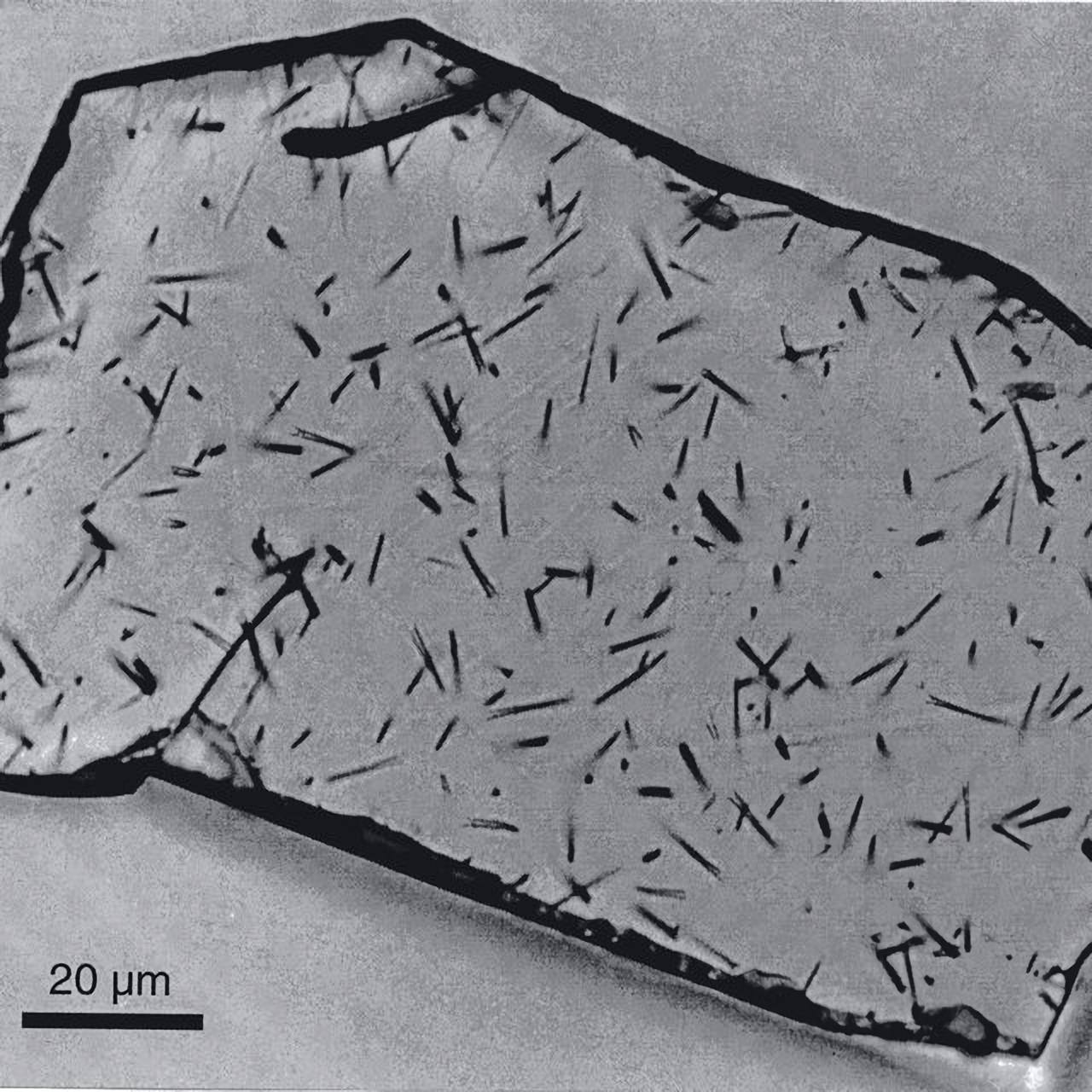

Soon after, in 1848, Virchow accepted a position as company surgeon at the Berlin Charité, and in 1849 he became the chair of pathological anatomy at the University of Würzburg. As his career progressed over the next seven years, he adopted the goals of his predecessors, Schleiden and Schwann, and sought to learn more about the human body at the cellular level. He does this by doing chemical and physical analyses on tissue samples beneath the microscope.

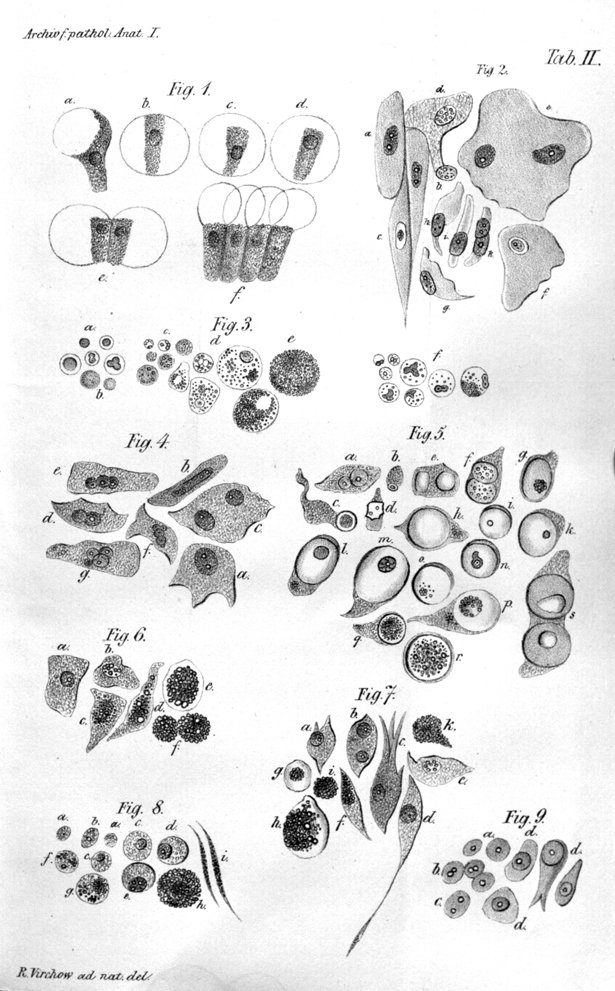

His results made a sensation when he presented them to his students at the Charité Institute of Pathology in Berlin, which had been established especially for him, and when they were published as a book in 1858.

Cellular pathology is established by Rudolf Virchow

“In the healthy as well as in the sick”

Rudolf Virchow discovers, contrary to what Schwann still believed, that cells originate not from some formless primordial slime but rather from other cells through cell division. In his seminal 1858 treatise on cellular disease, he states, “Omnis cellula e cellula,” or “Every cell emerges from a cell.”

Additionally, he claims that the cellular level is fundamental since it is the lowest unit of life. similar to an atom, which represents the lowest possible unit of substance that cannot be subdivided. Tissues, from the simplest muscle fibers to the most intricate neural networks and blood vessels, are assembled from these fundamental elements of life.

The fundamentals of health and illness

Using these two concepts, Rudolf Virchow brought Schwann and Schleiden’s cell theory to its natural conclusion. The thing is, he goes much farther in his thoughts. He wonders, “What happens in the body when someone is sick?” Yet again, he examines a wide variety of specimens with his microscope and draws conclusions, such as the finding that certain cells seem different in ill people than in healthy ones. Consequently, these fundamental components of life are the root of all sickness.

Rudolf Virchow sees this as a foregone conclusion, writing, “The disease has no other unit than life, namely the unitary living cell,” he writes. “It is, so to speak, the person of life, whether healthy or sick. And if Paracelsus forebodingly spoke of a body of illness, we can now say that the cell is this body.”

New unitary doctrine

According to Virchow, as a result of cell breakdown or dysfunction, a person gets ill. A doctor would treat patients more effectively if they knew exactly which cells were failing and in what condition.

It was a radical assertion at the time, and many professionals didn’t know how to approach it. The old humoral-pathological universal theory was crumbling, and as a result, Virchow’s idea of cellular pathology was gaining recognition as a new basic theory in medicine. As it turns out, he was right.

Basic ideas that have stood the test of time

Today, we know that Virchow’s theory that illness begins at the cellular level was right. Unhealthy cells may lead to diseases like cancer. Diseases of the immune system, such as MS and Crohn’s, manifest when the body’s defenses erroneously target the patient’s own healthy cells, tissues, and organs. When a virus infects a host, it invades healthy cells and reprograms them to produce more viruses.

According to Rudolf Virchow, the impact of bacteria and other microbes was still negligible. Even while pathologists can now delve far deeper into the cells and have long ago identified other, even smaller structures in these tiny living units, his work established a notion according to whose fundamental principles pathologists still operate today.

Leukemia was described by Rudolf Virchow

Focus on unexplored diseases

Rudolf Virchow’s seminal contributions to our understanding of cellular disease are especially well known today. The doctor, however, also gained prominence for his work in many other fields. Within the medical community, he was revered even during his lifetime, with titles like “Pope” and “Godfather of Medicine” being bestowed upon him by his peers.

It is about white blood cells

Rudolf Virchow was able to describe previously unknown ailments during his initial years in Berlin. In his study, “About the blockage of the pulmonary artery,” he examined the mechanisms behind vascular occlusion and first used the phrases embolism and thrombosis to describe them.

He was aware that blood clots in the lungs often form in the lower extremities. These thrombi then travel via the bloodstream to the distant pulmonary arteries, where they get lodged and obstruct blood flow.

As soon as Virchow finished writing this piece, he began work on another project: when dissecting the bodies of recently dead patients, he saw an abnormal luminosity in the blood, probably due to an enormous increase in the creation of white blood cells. In 1847, he was the first to use the Greek version of the word “leukemia” in medical practice. He did not yet understand, however, that the sickness originated in the bone marrow, the site where new blood cells are created.

Discreet proof

Virchow also made important contributions to forensic science. As the first medical professional, for instance, he examined hairs taken from a murder victim as part of a forensic inquiry.

Ultimately, he concludes that such samples can’t stand on their own as proof. Simply put, people’s hairs aren’t all the same. On the contrary, even when collected from the same individual, samples might show wide variation. On the other side, the hair on various people’s heads may seem quite identical at times.

A physician as a politician

Rudolf Virchow cares deeply about social and political problems

Virchow became well-known as a physician rapidly, and he soon began working for the Prussian government as well. He was in Upper Silesia at the time of the 1848 Berlin Revolution. He had been sent to the area as part of an important mission, looking into the origins of a deadly typhus outbreak.

“Politics is medicine on a large scale”

Because the people of Upper Silesia are famished and unwell, doctors there see a lot of suffering and need. His report on the state of affairs ends up becoming an accusation against the government, with Virchow claiming that the pandemic is the result of official indifference. Once he is back in Berlin, he joins the barricade struggle. He was fired from his position at the Charité because of this. But it’s the first step toward a successful political career.

Virchow explains “Medicine is a social science and politics is nothing more than medicine on a large scale.” Following this dictum, in 1859 he moved back to Berlin after studying at Würzburg. He was again elected to the Prussian Parliament two years later.

The near-duel

The well-being of the populace seems to be his core concern. Virchow strongly believed that in order for people to be healthy, they need access to clean water, fresh air, and basic medical treatment. He argues that Berlin needs new public hospitals and a water and sewage infrastructure. Rather than pouring huge resources into the military, he argues, the government should fund these much-needed infrastructural upgrades.

However, at first, there was resistance from the city fathers. Bismarck’s intransigence was also a source of irritation for Virchow. After a particularly heated argument over the state budget in the Prussian Parliament, the prime minister finally lost his cool and challenged Virchow to a battle. However, Virchow declines. He calmly teaches his opponent that a fight to the death is not a valid method of communication in the twenty-first century.

A sewer system for Berlin

Virchow keeps his eye on the ball: “All the wealth, all the importance of the city and the state is ultimately based on the activities of the residents.” He begs the question, “So can there be any greater loss than the loss of human life? Doesn’t every illness that incapacitates a member of society who is able to work bring disadvantages that can be estimated in monetary terms?”

However, his voice was finally heard when a typhus outbreak in 1872 killed more people in Prussia than were lost in the whole war with France. After coming to their senses, Berlin’s city fathers borrowed many million Marks over the next several years to fund the construction of a brand new water and sewage infrastructure. This initiative was a model for others to follow, and it would soon be complete in most of Germany’s main cities.

Anti-racist and devoted to eliminating racism

However, Virchow’s dedication to public health goes beyond his work in the German Parliament. Towards the end of the 19th century, anti-Semitism and xenophobia were gaining traction in the German Empire. Simultaneously, the notion that mental traits might be connected to bodily ones begins to take shape. The politician cautions against such generalizations, particularly those that lead to the denigration of a whole race.

Every time he had the chance, he bravely and eloquently refuted the beliefs of his political opponents, such as when he said, “It seems as if every member of the anti-Semitic party considers himself a primordial German.” He added, “I can refer you to the glorious times of our army and civil service. Everywhere you will find men who were now Celts, now Slavs, and now Italians and whatever.”

When a brochure in Berlin raises the specter of a Turk being elected to the city council in the future, he calmly tells the men reading it, “Yes, gentlemen, you would have to put up with that, too.”

Rudolf Virchow as an anthropologist

Skulls, Troy and schoolchildren in sight

Rudolf Virchow epitomizes the 19th-century polymath. Consequently, he leaves his imprint not just as a socially conscious doctor and pathologist, but also as a leader in his field. Comparable to the careers of anthropologists, ethnologists, and archaeologists, he was a huge success. Virchow established Berlin’s “Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory” and its accompanying Journal of Ethnology around 10 years after his seminal work in cellular pathology was first published.

About bones and skulls

According to historian Joachim Herrmann, “thus began a new epoch of historical-archaeological-anthropological research in Berlin and ethnographic research, significant for the German-speaking area as a whole.” Virchow and his team are working to provide a comprehensive compilation of the most recent results in the area of human studies. Scientists have an interest in studying previously undocumented societies and biophysical traits.

In order to achieve this goal, they collected everything that was brought back from excursions and far-flung adventures, including: The specialists also studied, debated, and catalogued human bones in addition to other objects like pottery. During this period, Virchow amassed his collection of over five thousand skulls and skeletons from different parts of the globe. Presently, the Anthropological Institute at Humboldt University is responsible for the so-called Virchow Collection.

Friendship with Schliemann

Heinrich Schliemann, an archaeologist, too believes he will benefit much from the Berlin society’s pooled scientific knowledge. Just recently, he had concluded his first dig in Troy, where he had discovered urns decorated with what seemed to be human faces; Virchow had just published a study on very similar facial urns from Pomerania.

The two researchers first connected in 1875 at a meeting in Berlin, when they shared their discoveries. The two experts have the same goal: to learn more about hitherto unexplored periods in global history. Together with Schliemann, Virchow travels to Asia Minor, Greece, and Egypt. He even lent a hand to an archaeologist pal who was working to uncover more of Troy. In the German translation of Schliemann’s 1881 book, “Ilios, Stadt und Land der Trojaner,” Rudolf Virchow was honored with a dedication.

The myth of the Proto-German

Virchow also attempted to utilize scientific arguments to counter the anti-Semitism and suspicions of alien infiltration that emerged in his native country in the 1880s. He started a study of German schoolchildren from an anthropological perspective, among other things. More than 6.7 million children’s hair, complexion, eye colors, and skull shapes are analyzed throughout all states.

The research was reported by the scientist in 1886, with the findings broken down by Jewish and non-Jewish participants. Approximately 30% of Germans were blondes, 14% were brunettes, and 54% were a mix of both sexes, according to the data. Virchow found that 47% of Jewish children were of mixed ancestry, 42% were of the black hair type, and 11% were of blond ancestry. As he had suspected, this proved that no really pure racial groups exist in Germany. Naturally, the representatives of the nationalistic and racially ideologically shaped “Völkisch Movement” did not like this realization at all.

Errors of Rudolf Virchow

The areas where the brilliant scientist went wrong

Virchow achieved greatness in the annals of medical history thanks to the development of the concept of cellular pathology and his work to improve public health. While the bright scientist may have been farsighted in certain areas, this was not the case for him throughout his life. Even he made mistakes.

Arguments against the “bacillus circus”

Robert Koch, a contemporary of Virchow’s, had firsthand experience with this: like his mentor, Koch sought the root causes of sickness. In contrast to popular belief, his target is not the body’s cells but rather its microscopic, “invisible,” and pervasive foes, bacteria. He speculates that these microscopic creatures may have a role in the spread of illnesses like TB and anthrax.

However, Virchow dismisses this as utter rubbish. He mocks the “bacillus circus” and his Berlin University coworker’s theory as too radical and unsubstantiated. This remains true even when Koch eventually finds the causative agents of a wide variety of infectious illnesses and demonstrates that their transmission can be effectively limited by targeted procedures like hand washing.

There is no acknowledgment of coworkers

The University of Würzburg, where Virchow previously worked, attributes his dogged persistence in the face of mounting, contradictory findings to his enormous self-confidence and, perhaps, a certain tendency toward vanity. “While Virchow defended his own hypotheses with an almost Lutheran self-assurance, he had great effort to acknowledge pioneering work by other great researchers,” the university writes in a treatise on the history of the Institute of Pathology.

However, it is precisely what there was an abundance of back then. In fact, Virchow isn’t the only one who benefited from the technological advancements of his day. Thus, bacteriology is only one of several scientific disciplines that formed or made important strides in the course of the 19th century.

Doubtful about Darwinism

The university’s report continues, “Sometimes one has the impression that Virchow would have accepted their ideas enthusiastically if they had only sprung from his own insight.” So, the researcher’s skepticism may have been mitigated if he’d known both explanation models were viable and complementary. However, this is only established in retrospect.

The evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin, whose Origin of Species was published a year after Virchow’s Cellular Pathology, was another contemporary of Virchow’s who he found wanting. According to Virchow, the ideas presented here can only serve as an intriguing thinking experiment. While he acknowledged that evolution had occurred in all living things, he did not think it applied to humans.

Misunderstanding in Neanderthals

As a result, Virchow disagreed with the naturalist Johann Carl Fuhlrott, who had concluded that the skull bones recovered in the so-called Kleine Feldhofer Grotte near Düsseldorf belonged to an ancient man due to their unusual form. He casts doubt on Fuhlrott’s (1859) theory that human fossils exist and instead proposes a pathological explanation, arguing that the bones really belong to a living person but have been pathologically transformed.

Rudolf Virchow’s worries were taken seriously since he was not only a respected medical expert of his day. That’s why it’s been assumed for decades that the discovery belonged to a weak modern person. But Virchow had made a major mistake once again; the skeleton was really that of a Neanderthal, who lived around 42,000 years ago.

Bibliography

- “Virchow”. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language.

- Appleton’s Annual Cyclopædia and Register of Important Events of the Year … – Google Books

- Bagot, Catherine N.; Arya, Roopen (2008). “Virchow and his triad: a question of attribution”. British Journal of Haematology. 143 (2): 180–190. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07323.x. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 18783400. S2CID 33756942.

- Taylor, R; Rieger, A (1985). “Medicine as social science: Rudolf Virchow on the typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia”. International Journal of Health Services. 15 (4): 547–559. doi:10.2190/xx9v-acd4-kuxd-c0e5. PMID 3908347. S2CID 44723532.

- Boak, Arthur ER (1921). “Rudolf Virchow—Anthropologist and Archeologist”. The Scientific Monthly. 13 (1): 40–45. Bibcode:1921SciMo..13…40B. JSTOR 6581.^