Ivan IV (1547–1584)

Ivan the Terrible did not even consider claiming the Byzantine Empire after accepting the tsarship as the true heir of the Greek rulers. Of the rights of Constantinople’s rulers, he assimilated only one: the right to be regarded as the representative and protector of universal Orthodoxy. The tsars in Moscow did not see themselves as freeing Orthodox countries from Turkish rule.

“We wish that you too may receive mercy from God, as a cup full of dissolving, and be delivered in these days from the languor of blasphemers, and we, hearing of this, rejoice and offer victory song to God in glory and honor His name,” Ivan IV wrote to the patriarch of Constantinople after the conquest of Kazan and Astrakhan.

But Russian rulers, who thought they were freeing the Orthodox countries from Turkish rule, began to push them as early as the 16th century. The Patriarch of Constantinople called Ivan the Terrible “the hope of all Christian families, whom he will deliver from barbaric hardship and bitter work” in his letter approving his royal wedding; he writes that he and the entire council pray God to strengthen his kingdom and raise his hand, “may he deliver all Christian families everywhere from the foul barbarians, cheese eaters, and terrible pagan Hagarites.”

Aleksey Mikhaylovich (1645–1676)

The legend of Moscow’s tsar as the ultimate conqueror of the Turks gained steam throughout the course of the 17th century. By overthrowing the Polish government, the Greeks were given optimism that Tsar Aleksey Mikhaylovich would also attack the Turks after annexing Little Russia after Bogdan Khmelnytsky’s uprising. Khmelnitsky and Moscow relied heavily on the help of Patriarch Paisii of Jerusalem as a mediator. The Patriarch of Constantinople and many other Greeks, both religious and not, also pushed for Russia to take over Malorossia.

Peter I (1682–1725)

Peter the Great had designs on the Balkans and the Middle East, despite his preoccupation with the conflict in the North. Russia’s inability to enter the Sea of Azov (which took Russians to Dagestan and the Caspian Sea) after its 1711 Prut campaign and its 1722–1723 Persian campaign are examples. Conditions apparently prompted the first Russian monarch to attempt to conquer Constantinople. Field Marshal Minich was inspired by this notion, and it was via him that Catherine the Great (Catherine II) learned about Peter the Great’s military preparations.

Once at the celebration of Paul Petrovich’s birthday, Minich told Catherine: “I desire that when the magnificent prince reaches seventeen years of age, I can congratulate him generalissimo of Russian forces and take him to Constantinople to listen to mass in the cathedral of St. Sophia.” They could call it a mirage, much like they did when the Rogervik Baltic port was built. I can only attest to the fact that Great Peter, from the time he laid siege to Azov in 1695 until his death, never wavered in his pursuit of his most cherished objective: the conquest of Constantinople, the expulsion of the Turks and Tatars from Europe, and the restoration of the Christian Greek Empire. I can, most gracious sovereign, propose a plan for this vast and important enterprise. Unfortunately, after spending several years developing this strategy in exile, it was destroyed when I switched to my new fortification scheme. It’ll require some time for reflection and redrawing.

Anna Ioannovna (1730–1740)

During the wars of 1735–1739, which most lauded Burkhard Christoph von Münnich, Anna Ioannovna also considered an attack on the Turkish capital. Alexey Veshnyakov, an assistant Russian resident, wrote to St. Petersburg, imagining the Crimean Turks’ demise: “In this situation, they can’t do anything else; everything is at risk.” In this case, they can’t do anything else except initiate a formal war against our kingdom. If you can grasp it, Constantinople’s demise will be imminent.

Münnich outlined a “general strategy for war” in a letter to Ernst Johann von Biron in the spring of 1736. In 1736, the self-confident commander appointed the capture of Azov; in 1737, the Crimea; in 1738, Moldavia and Wallachia; and about the next year, he wrote:

In 1739 the flags and standards of her country are hoisted … where? – In Constantinople. In the first, the oldest Greek-Christian church, in the famous Hagia Sophia, she was enthroned as empress of Greece, and given peace… to whom? – To a world without limits, no – to nations without numbers. What a glory, what an empress! Who will ask then to whom the title of emperor belongs? “To him who is crowned and anointed in Frankfurt, or to her who is in Istanbul?

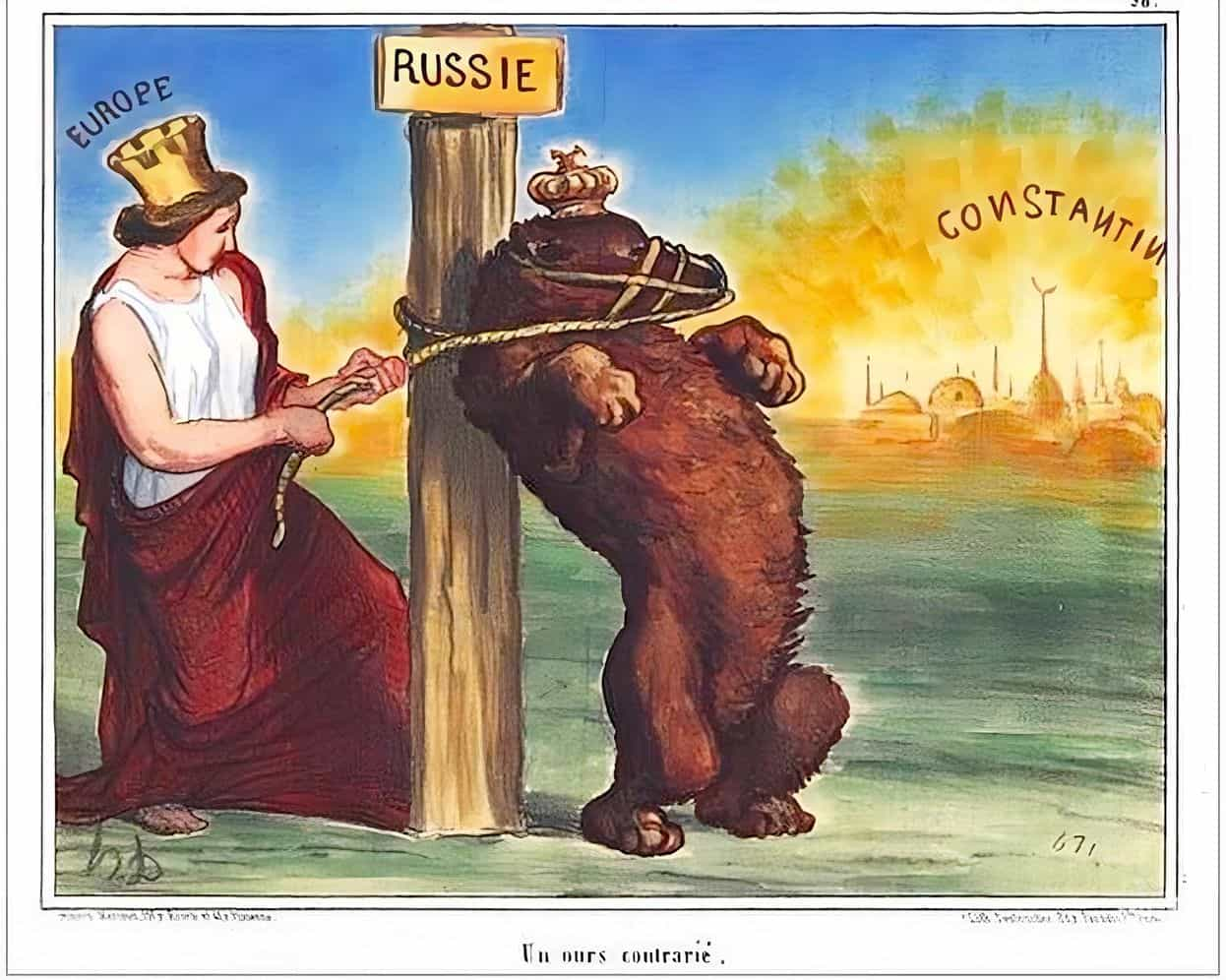

Catherine the Great (1762–1796)

During the Russo-Turkish War that raged from 1768 to 1774, Catherine the Great focused only on securing Russia’s access to the Black Sea. However, the empress indicated through her military commanders that the war was being undertaken for the freedom of the Orthodox peoples of the Balkans from the oppression of the Ottomans.

Greek nationalists, inspired, flocked by the hundreds to the Russian flags, while the local intellectual elite were also buoyed. In July 1771, Catherine of Russia invited the scholar and clergyman Eugenios Voulgaris to visit her. While there, he voiced his disappointment to the royal audience that Catherine was not a Greek empress, saying, “Greece, after God looks up to you, you pray, you cling.” Following that, he outlined his plan for resolving the Eastern Question. As Voulgaris put it, “The split of the Turkish provinces in Europe, along with the formation of a little autonomous Principality of the Greek Nation, may enable us in the future to sustain a true European balance.“

Bibliography

- A .A. Kochubinskij. Count Andrey Osterman and the partition of Turkey. From the history of the Eastern question. Five Years War (1735-1739).

- Nikolai Fedorovich Kapterev. The Nature of Russia’s Relations with the Orthodox East in the XVI and XVII Centuries, Sergiev’ Posad, M. S. Elova, 1914.