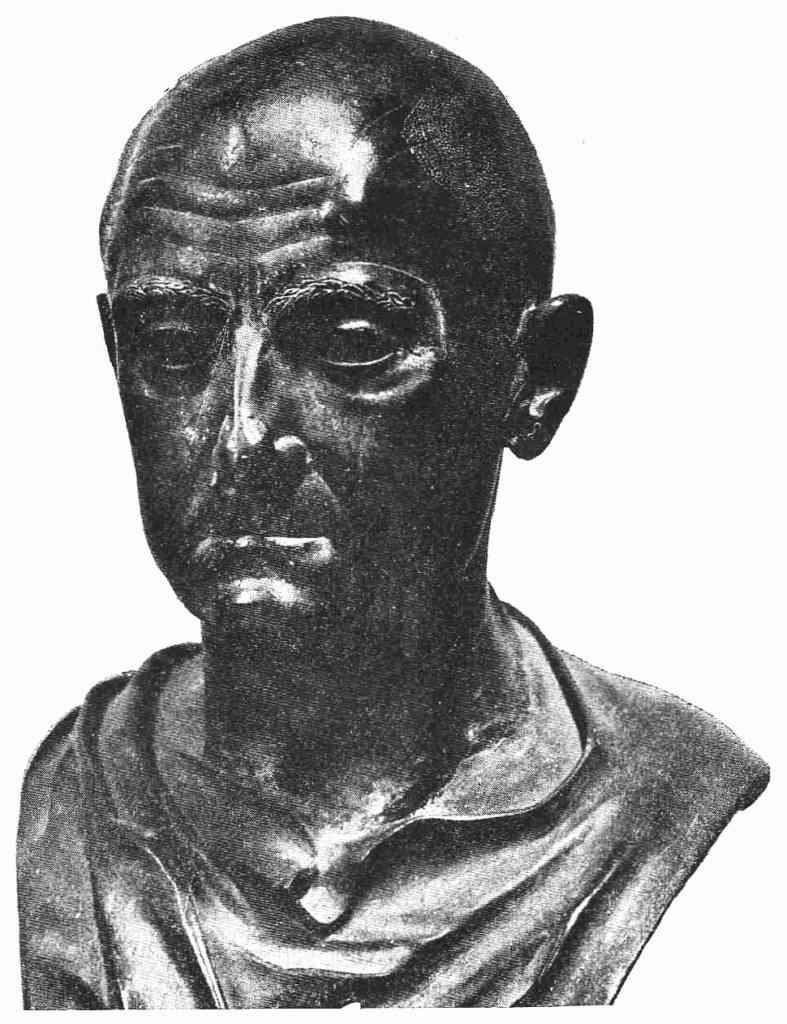

Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus Africanus (185/184—129 BCE) was a Roman military commander and political figure from the patrician Cornelii Scipiones family, consul in 147 and 134 BCE. He was the son of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus and, through adoption, became part of the Scipiones family, becoming the adopted grandson of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus. He participated in the Third Macedonian War. In the subsequent years (167—152 BCE), he became one of the most prominent representatives of the aristocratic youth of Rome and the leader of an intellectual circle known as the “Scipionic circle.” This circle included Polybius, Gaius Laelius Sapiens, Lucius Furius Philus, and other politicians and intellectuals.

Publius Cornelius began his career in 151 BCE with military service in Hispania Ulterior under the command of Lucius Licinius Lucullus. He quickly earned a reputation as a brave and capable officer. From 149 BCE, Scipio Aemilianus participated in the siege of Carthage during the Third Punic War. The military actions were generally unsuccessful, and in many cases, it was only Publius Cornelius who saved the Roman army from significant defeats. Therefore, he was prematurely elected consul in 147 BCE and led the African army. After fierce battles, Carthage was captured and destroyed in 146 BCE. Scipio was honored with a triumph and the honorary title “Africanus.” In the following years, he was one of the most influential politicians of the Roman Republic: he held the position of censor in 142 BCE, and several members of his circle obtained the consulship. However, Scipio led a generally unsuccessful struggle against the “faction” of the Caecilii Servilii. A plan for reforms in favor of the plebs was developed in his “circle,” but Scipio abandoned the implementation of this plan due to possible resistance in society.

In 134 BCE, Publius Cornelius obtained his second consulship and command in the war against the Spanish city of Numantia, near the walls of which the Romans had already suffered shameful defeats. Scipio managed to discipline the besieging army and take Numantia after seven months of fighting. During the intense internal political struggle in Rome that began at this time (in 133 BCE) between the Senate and the plebeian tribune Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, he sided with the Senate, although Gracchus was his close relative, and approved the tribune’s assassination. Later, Scipio led the conservative “party,” opposing reformers such as Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, and Gaius Papirius Carbo. He managed to effectively halt the redistribution of land in Italy and thwart the initiative to allow plebeian tribunes to be re-elected, but in doing so, he lost the support of the people. In the midst of this struggle, in 129 BCE, Publius Cornelius died. Since his death was sudden, his opponents were suspected of involvement in his assassination.

Biography

Origin

By birth, Publius Cornelius belonged to the distinguished patrician family of the Emilii, which ancient authors considered one of the oldest families in Rome. One of the eighteen oldest tribes was named in honor of this family. Their genealogy was traced back either to Pythagoras or to the second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, and one version of the tradition, cited by Plutarch, calls Emilii the daughter of Aeneas and Lavinia, who gave birth to Romulus by Mars—the legendary founder of Rome. According to Plutarch, representatives of this family were distinguished by “high moral qualities, in which they constantly perfected themselves.” In the 3rd century BCE, the Emilii regularly held the consulship, and in historiography, they are referred to as the nucleus of one of the “political cliques seeking to seize all power entirely.” Their political allies included the Livii, Servilii, Papirii, Cornelii Scipiones, Veturii, and Licinii.

The cognomen Paulus means “small” or “humble.” Publius’s great-grandfather was Marcus Aemilius Paullus, consul in 255 BCE, who fought against the Carthaginians at sea during the First Punic War; his grandfather was Lucius Aemilius Paullus, consul in 219 and 216 BCE, who commanded in the Second Illyrian War and perished in the Battle of Cannae. The daughter of this nobleman, and thus Publius’s aunt, Aemilia Tertia, became the wife of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus.

Publius’s father was the twice-consul (in 182 and 168 BCE) Lucius Aemilius Paullus, who received the agnomen Macedonicus for his victory over King Perseus in 168 BCE. Publius’s mother, Papiria, belonged to the patrician Papirii family. Her father, Gaius Papirius Maso, was consul in 231 BCE and, after defeating the Corsicans, became the first of the Roman commanders to celebrate a triumph against the will of the Senate.

Papiria bore Paulus two sons, the second of whom was the future Publius Cornelius. Soon after their birth, Lucius Aemilius divorced his wife for unknown reasons and remarried. In his second marriage, he fathered two more sons, and he gave his eldest sons up for adoption to other patrician families: the first to Quintus Fabius Maximus (presumably the grandson of Cunctator), and the second to Publius Cornelius Scipio. From that moment on, the young Emilius bore the name Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus.

As an adopted son, Publius was a blood cousin to Scipio’s two sons, Scipio Aemilianus and Maximus Aemilianus, who, due to poor health, refrained from pursuing a career but nevertheless held a high position in society due to their lineage. In addition to the two blood brothers, Scipio Aemilianus and Maximus Aemilianus, Scipio’s daughters later appeared. Emilia later became the wife of Marcus Porcius Cato Licinianus (son of Cato the Censor), and the other became the wife of Quintus Aelius Tubero, a representative of an ancient but very poor patrician family.

Early years

The future Scipio Aemilianus was born in late 185 or early 184 BCE. Researchers cannot determine a more precise date because the sources are contradictory. On the one hand, Titus Livius and Diodorus Siculus report that on the day of the Battle of Pydna (June 22, 168 BCE), Publius Cornelius was seventeen years old. On the other hand, Polybius, recounting his first meeting with Scipio Aemilianus, which could not have taken place before the beginning of 166 BCE, says that he was “not more than eighteen years old” at that time. And Diodorus confirms that Scipio was indeed this age when he made Polybius his mentor.

Publius Cornelius passed away, according to some sources, shortly before his 56th birthday. This occurred immediately after the completion of Marcus Tullius Cicero’s treatise “On the State,” shortly after the Latin Games of 129 BC. These games took place in April or May, indicating 185 BC as the year of birth. Apparently, in antiquity, there was no consensus on when Scipio Aemilianus was born; this may be indicated by the message of Gaius Velleius Paterculus: “He died at almost 56. If anyone doubts this, let him refer to his first consulship, to which he was elected at the age of thirty-six, and doubts will disappear.”

Plutarch writes that Scipio Aemilianus lived for 54 years, but there may have been a simple confusion here: the Greek writer may have mistaken the Roman numeral VI for IV.

After formally joining the Cornelius Scipio family, Publius continued to live in the house of his biological father, as did his elder brother, named Quintus Fabius Maximus Aemilianus. According to Plutarch, Lucius Aemilius loved his sons more than any other Roman; the Aemilian brothers received an excellent education, blending ancient Roman traditions with Greek ones. One of Publius Cornelius’s mentors was Marcus Porcius Cato the Censor. According to Cicero, both the youth’s biological and adoptive fathers decided that Publius should dedicate all his free time to Cato, taking lessons in practical wisdom from him.

In 168 BC, Scipio Aemilianus and Maxim Aemilianus accompanied their father, who commanded in the Third Macedonian War, to the Balkans. Publius Cornelius participated in the victorious battle of Pydna for Rome and became so engrossed in pursuing the enemy that he returned to the camp only at night. By that time, his father had already suspected that Publius had perished, “getting entangled through inexperience in the very midst of the enemy,” and the soldiers, who loved Scipio Aemilianus, searched for his body among the fallen.

The victory at Pydna meant the end of the war, but the Roman army remained in Macedonia for over a year. During this time, Lucius Aemilius Paullus granted Publius the right to hunt in the royal forests, and as a result, he became a passionate hunter for life. Additionally, Paullus presented the sons with the library of King Perseus, which was later taken to Rome. In the autumn of 168 BC, Paullus took his son on a journey through Greece. Through Thessaly, the Romans reached Delphi, then visited Euboea, Athens, Corinth, Sicyon, and the cities of Argolis, Sparta, and Olympia. It was Publius who later told Polybius about the immense impression made on his father by the statue of Zeus made by Phidias.

Upon returning to Rome the following year, Scipio Aemilianus, like Maxim Aemilianus, took part in his father’s triumph. Both of them followed the triumphator’s chariot. In those same days, Publius Cornelius lost both of his blood brothers, who suddenly died one after another (one was 14 years old, the other 12).

Youth

In the years following the Macedonian War, Scipio Aemilianus was only engaged in hunting and books, showing no interest in public affairs. Contrary to the custom at the time, he did not attend the forum and did not attempt to bring a lawsuit against any prominent nobles for the sake of fame. Therefore, he was considered a man devoid of ambition, lazy, and lethargic, whose behavior did not correspond to his distinguished lineage.

The decisive turning point in Scipio Aemilianus’s life was his acquaintance with one of the hostages provided to Rome by the Achaean League, the son of the strategos Lycurgus, Polybius. This Achaean first came to the house of Lucius Aemilius Paullus on some business related to books, and thus began a great friendship, the fame of which, according to Polybius himself, “spread throughout Italy and Greece.” The Aemilian brothers managed to persuade Polybius to remain in Rome unlike the other hostages sent to Italian municipalities. Shortly thereafter, a fateful conversation took place for Publius Cornelius, the story of which is preserved in Polybius’s “Universal History.”

Scipio Aemilianus asked his Greek friend, Publius, why he constantly conversed only with his brother Quintus, seemingly neglecting him, Publius:

“Perhaps you think of me as my fellow citizens do, about whom I have to hear. Everyone considers me a man of immobility and lethargy — these are their words, and since I do not engage in conducting cases in court, then completely devoid of the qualities of a Roman with an active character. Not such qualities, but directly opposite, they say, should distinguish a representative of the house to which I belong. This saddens me more than anything.”

— Polybius. Universal History, XXXII, 9, 9—12

Polybius, astonished by these words, explained to Scipio that he does not neglect him and that Publius’s feelings “reveal a noble soul.” He offered to teach his friend to speak and act as befits a person of his lineage, and this proposal was warmly received:

Polybius had not yet finished when Publius grabbed his right hand with both hands and, squeezing it with feeling, said: “If I live to the day when you leave all other matters, devote your energies to me, and live with me. Then, perhaps, I myself would soon find myself worthy of both our house and our ancestors.”

— Polybius. Universal History, XXXII, 10, 9—10

From that moment on, Polybius became Scipio’s constant companion. The latter began to deliberately cultivate strength of character, gave up any excesses, and physically toughened himself (thanks to this circumstance, he later emerged victorious from a series of military contests). Publius continued to be passionate about hunting, but alongside this, he began to attend the forum and sought not to return home without acquiring at least one new friend. Within five years of the memorable conversation with Polybius, he acquired an excellent reputation and became widely known in Rome.

Publius Cornelius was particularly renowned for his generosity toward his closest relatives. After the early death of his adoptive father and the passing of his mother, Emilia Tertia (162 BC), Publius found himself the sole inheritor of Scipio Africanus’ estate. Since his biological mother, Papiria, lived modestly after their divorce and was forced to forego participation in public processions, Scipio Aemilianus gifted her all of Emilia Tertia’s adornments, her sacrificial vessels, horses, and chariots that accompanied her during ceremonial appearances of slaves and handmaidens. Such a display of filial piety added to Publius’s popularity. However, when Papiria passed away (approximately in 159 BC), Scipio distributed all her inheritance, including what once belonged to Emilia, among his sisters, although by law they had no rights to the property.

As the head of the Scipio family, Scipio had to pay the remaining half of his aunts’ dowries (the daughters of Scipio Africanus) to their husbands, Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Corculum and Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, twenty-five talents each. In Rome, it was customary in such situations to pay in equal installments over three years, but Gracchus and Nasica, who came for the first installment, unexpectedly received the full amount. They were about to inform Scipio Aemilianus of their mistake when he responded that he did not approve of calculating matters with relatives.

In 160 BC, Publius’s biological father passed away. In the absence of other heirs, he bequeathed his estate to the Aemilii, although they had joined other families. Scipio renounced his share, amounting to sixty talents, in favor of his elder brother, so that he could equal him in wealth. Additionally, he covered half the expenses of the funeral games, although they were given on behalf of Quintus Fabius. All these examples of selflessness glorified Publius Cornelius even before the start of his political career.

In the 150s BC (exact dates are unknown), Scipio Aemilianus entered the Senate and married Sempronia — his cousin by blood and his adoptive sister; presumably, this marriage was purely political. During this period of Publius’s life, he undertook a significant journey through Italy and Transalpine Gaul for educational purposes. It is known that Polybius accompanied Scipio, and Publius Cornelius inquired about Britain from the residents of Narbo, Massilia, and Corbilo, albeit without much success.

“The Scipionic Circle”

In the 160s BC, around Publius Cornelius, a circle of friends and like-minded individuals began to form, distinguished from other members of the Roman nobility by their sympathies towards Greek culture and their disdain for vulgar entertainment. Many of them were connected by blood or old family ties. Researchers attribute to the “Scipionic Circle,” which lasted for over 30 years, senior contemporaries of Publius such as Gaius Laelius the Wise and Manius Manilius, his peers Spurius Mummius, Lucius Furius Philus, Publius Rupilius, and Quintus Pompeius (Cicero reports on this friendship circle of peers). It also includes Polybius, the philosopher Panaetius, Publius’s nephew Quintus Aelius Tubero; A. Bernstein associates Publius Mucius Scaevola (consul in 133 BC) with the “Scipionic Circle,” A. Astin includes Lucius Postumius Albinus (consul in 154 BC), Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Porcina, Publius Licinius Crassus Mucianus, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi, Marcus Fulvius Flaccus (consul in 125 BC), the poet Gaius Lucilius, and the playwright Publius Terentius Afer. Y. Zaborovsky, basing his argument on Cicero’s treatise “On the State,” suggests that the circle also included Gaius Laelius’s sons-in-law Quintus Mucius Scaevola Augur and Gaius Fannius, as well as Publius Rutilius Rufus and the poet Marcus Pacuvius. According to A. Gruen, most of the prominent political figures of Rome in the 140s BC belonged to this “circle.”

Scipio Aemilianus’s closest friend became Gaius Laelius, the son of a “new man” who had been the best friend of Scipio Africanus. Perhaps Publius and Gaius met at a very young age; in any case, by the 160s BC, they were already as close friends as their grandfathers and fathers respectively. Until Scipio Aemilianus’s death, Laelius was his constant companion and like-minded friend. Cicero puts the following words into the mouth of Gaius Laelius:

There is no treasure that I could compare with the friendship of Scipio. In it, I found agreement on state affairs, advice on personal matters, and relaxation filled with joy. I have never offended him, as far as I know, not even with some trivial matter, and I have never heard anything unpleasant from him. We shared one house and one meal at the same table. Not only outings but also journeys and life in the countryside were shared by us. Do I need to speak about our constant efforts to learn and study something when we, far from the eyes of the people, have devoted our leisure time to this?

— Cicero. On Friendship, 103–104.

Together with their friends, Scipio Aemilianus supported talented writers who did not enjoy success among the general public due to their coarse taste. Thus, from 165 to 160 BC, he maintained close friendly relations with Publius Terentius, in whose comedies, according to rumors, both Publius Cornelius and Laelius inserted fragments written by themselves. There was even an opinion that Scipio and Laelius staged their own plays, using another person’s name as a cover, and Terence did not refute such rumors, but rather supported them. For example, in the prologue to the comedy “The Brothers,” he writes that such rumors are pleasant to him, as they indicate that his plays are liked by the most popular people in Rome. According to Suetonius, the playwright acted on the assumption that these rumors were pleasing to his patrons.

Sources do not report any attempts by Scipio and Laelius to clarify this issue. Cicero and Quintilian provide information about the possible authorship of the two friends as something that could be true but is unproven; the grammarian of the 1st century BC, Santra, argues that Laelius and Scipio could not have written the plays attributed to Terence due to their young age. Some researchers suggest that Scipio and Laelius could indeed be the true authors of his plays; others dispute this opinion, not denying that Terence could receive advice and agree to “something like editing.”

There were also rumors that Terence was involved in a romantic relationship with his patrons and that’s why he went to Greece after his separation and perished there, without receiving help and in complete poverty (160 BC). But Suetonius treats this version with skepticism, saying, among other things, that after Terence, there remained a garden of 20 jugers along the Appian Way, and his daughter became the wife of a Roman knight. The surviving epigram by Porcius Licinus about the “debauched nobility” and Terence is clearly defamatory.

In 155 BC, three Athenian philosophers visited Rome — the Academic Carneades, the Peripatetic Critolaus, and the Stoic Diogenes. Scipio Aemilianus, together with Gaius Laelius and Lucius Furius Philus, became their regular listener. Later, the outstanding Stoic Panaetius settled in the house of Publius Cornelius. Later, after 146 BC, when Publius Cornelius returned from Africa, he became close to the poet Gaius Lucilius, who became an important member of the “Scipionic Circle”:

…When Scipio or Laelius, serene sage,

Retired from the crowd and from the concerns to peace,

He often loved to joke and converse with them simply,

While they prepared vegetables for their meal.

In Laelius’s house, with Scipio’s participation, readings of Lucilius’s “Satires” were organized.

It was precisely in the “Scipionic Circle” in the 150s BC that the concept of the “mixed constitution” emerged, as outlined in the sixth book of Polybius’s “Histories.” Cicero names Publius Cornelius as its author. According to this concept, the political structure of the Roman Republic successfully combined elements of the three main forms of government as per Plato and Aristotle — democracy, monarchy, and aristocracy. The first of these forms found its embodiment in the popular assembly, the second in the institution of the consulate, and the third in the Senate. As a result, the Greek classification was filled with concrete Roman content.

Beginning of Military Career

Scipio Aemilianus began his career in 151 BC, when he was 33 or 34 years old. At this time, the incumbent consuls, Lucius Licinius Lucullus and Aulus Postumius Albinus, attempted to recruit armies to continue the war in the Spanish provinces, but encountered serious difficulties. The Romans, frightened by reports of constant uprisings on the Iberian Peninsula and the defeats suffered by provincial troops, tried in every way to avoid conscription. Particularly dramatic was the absence of young aristocrats who would want to go to Spain as military tribunes (usually there were several contenders for each such position).

In this situation, Publius Cornelius announced his readiness to go to the Pyrenees with any of the consuls. At that time, he was called by the Macedonians to settle internal disputes, and this mission promised to be quite comfortable and safe, but Scipio decided that Rome needed him more in the West. His statement was a complete surprise and had an effect: the consuls were finally able to recruit people and set off to their provinces. However, some historians argue that Polybius and Appian, who sympathized with Publius Cornelius, somewhat distorted the facts; they could exaggerate the situation, portraying Scipio’s importance for the successful outcome of the matter.

Publius Cornelius found himself in Lucullus’s army, which was tasked with governing Near Spain. According to the epitomator Livy, Scipio was a military tribune; according to Appian, Lucius Ampelius, and Pseudo-Aurelius Victor, he was a legate. Polybius limits himself to a neutral formulation (“in the rank of either a tribune or a legate”). The author of the classical reference book R. Broughton considers the first option more likely, while the German researcher G. Simon favors the second.

The campaign of 151 BC turned out to be extremely scandalous. Lucullus’s predecessor had managed to conclude an honorary peace with the enemy, but the new governor, eager for glory and plunder, started a war with the friendly tribe of Vaccaei. Thanks to a treacherous stratagem, he managed to take the city of Caucia, whose population he massacred, but after a series of battles, he made an agreement with the inhabitants of Intercatia and was forced to retreat from Palantia with losses.

Scipio Aemilianus is only mentioned in connection with the siege of Intercatia. A Vaccaean horseman came out of the city every day to challenge one of the Romans to combat; finally, Publius Cornelius, after much deliberation, accepted the challenge. In a horseback duel, he “happily overcame this huge man,” and this victory lifted the spirits of the Roman army, while it had the opposite effect on the opponent. Soon, the besiegers breached the wall and broke into the city; Scipio Aemilianus was the first to enter, earning a “wall” crown (corona muralis) for this feat. However, the Romans were immediately pushed into some artificial reservoir for water and mostly slaughtered there, but Publius Cornelius managed to break through to his own. It was during this battle that he might have saved the life of a certain Marcus Aelius Pelignus, shielding him with his shield, and then killing his opponent (this episode is mentioned by Cicero in his “Tusculan Disputations”).

During the prolonged siege, both sides suffered serious difficulties due to a lack of food. Eventually, an agreement was reached, and Scipio signed it on behalf of Rome: presumably, the Vaccaei trusted him as a brave warrior or remembered his father’s governorship in Near Spain from 191 to 189 BC. Lucullus’s army received 10,000 cloaks, some cattle, and 50 hostages.

Scipio, who sought to establish a reputation as a valiant warrior during this campaign, clearly disapproved of Lucullus’s treacherous behavior. However, due to circumstances related to military recruitment, Publius may have had more influence in the consular army than a regular legate or military tribune. Presumably, this is why Lucullus decided to send Scipio to the allied Numidia for elephants and cavalry. This trip could have taken place either before the siege of Intercatia (G. Simon even suggests that Publius Cornelius went to Africa directly from Rome) or after it.

At that time, the Numidian king Masinissa was at war with Carthage. Publius Cornelius arrived at the king’s camp on the eve of a major battle, observing it “from a height, as if in a theater.”

And often later he said that, participating in all kinds of battles, he had never enjoyed it so much: because, he said, for this one battle, where 110,000 men clashed in battle, he watched carefree. And, using a somewhat elevated tone, he said that only two before him had seen such a spectacle during the Trojan War. Zeus from Mount Ida and Poseidon from Samothrace.

— Appian. The Punic Wars, 71

The battle ended in a victory for the Numidians. Learning that the grandson of Scipio Africanus was in the enemy army’s camp, the Carthaginians asked him to mediate in concluding peace. Publius Cornelius almost succeeded in this mission: Carthage agreed to cede disputed territory around the city of Emporia to Masinissa and pay a tribute (200 talents of silver immediately and another 800 later), but rejected the demand to surrender hostages. As a result, peace was not concluded. Historiography notes that Publius Cornelius’s attempt to settle the conflict ran counter to the basic principles of Roman policy in Africa: the Romans consistently sought to escalate the situation in this region, pushing the Numidians to new territorial seizures.

Masinissa provided Publius Cornelius with the best reception, as it was to the Scipio family that the king owed his throne. Publius received both elephants and auxiliary troops, which he brought to Lucullus. Later, the governor sent “his best commanders” to repel the Lusitanian raid, among whom Scipio could have been.

By the end of the summer of 150 BC, Scipio was already in Rome. It is known that he persuaded Cato to speak in the Senate in favor of allowing the Achaean hostages to return home “for the sake of Polybius.” At that time, Marcus Porcius said, “— As if not knowing what to do, we sit all day and discuss whether our undertakers or the Achaeans will bury Greek elders.” As a result, the hostages were able to return home.

Third Punic War: Military Tribune

In 149 BC, Rome, using the pretext of another clash between Numidia and Carthage, declared war on the latter. Publius Cornelius secured his election as a military tribune. Since Africa was considered a sort of “hereditary province” of the Scipios, his cousins Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Serapio and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Hispanus were with him as part of the army, which was to take and destroy Carthage. This army, under the command of the consuls Manius Manilius and Lucius Marcius Censorinus, landed in Utica and began the siege of Carthage; the Senate issued a secret order not to end the war until the city was destroyed.

The enemy unexpectedly offered vigorous resistance and repelled the attempts of the Romans to take Carthage by storm. A protracted war began, in which the besieging Roman army had to act against both Carthage and the enemy’s field forces. Manilius and Censorinus were not very competent commanders; in this situation, Scipio Emiliano’s successful actions became the focus of attention. Publius Cornelius first made himself heard after the Romans’ attempt to break into the city through a breach in the wall in the autumn of 149 BC. From the beginning, he did not believe in success, so he positioned his unit near the breach from the outside. The assault unit was repelled by the enemy, and it was only thanks to Scipio Emiliano’s covering action that they were not completely wiped out. According to Appian, on that day Scipio “showed himself to be more far-sighted and cautious than the consul.”

Soon one of the consuls, Censorinus, left for Rome, and the Carthaginians became even more energetic. During a nighttime attack on Manilius’ camp, they crossed the ditch and began to destroy the rampart, causing panic among the Romans. Publius Cornelius once again saved the situation: he led the cavalry out through the gates far from the site of the attack and struck the enemy in the rear, forcing them to retreat.

After these events, Manius Manilius expanded his operations into the interior of the country. His army plundered enemy lands, gathering food, forage, and building materials. Meanwhile, the enemy’s light cavalry under the command of Himilco Phameas constantly attacked the Romans, inflicting significant losses. The foraging detachments, which were alternately commanded by military tribunes, suffered the most from these attacks. But Scipio Emiliano raised discipline in his units to such a level and organized foraging so skillfully that Phameas did not dare to attack him. Because of this, Publius Cornelius’s colleagues began to spread rumors out of envy that there were friendly relations between him and Phameas.

Unlike other tribunes, Publius Cornelius, when accepting the surrender of local residents, always kept his word and even escorted the surrendering parties to fortified cities; therefore, from a certain moment, the Libyans agreed to surrender only to him. Immediately upon returning to the camp near Carthage, Scipio again distinguished himself: the besieged attacked the fortification near the harbor at night, and Publius led 640 horsemen out of the camp with torches and organized such a convincing demonstration that the enemy retreated, fearing encirclement.

Later, Manius Manilius decided to move on to Nepheris, against the Carthaginian commander Hasdrubal Boethar. Scipio expressed his opposition to this campaign, citing the uneven terrain and the fact that all the heights were occupied by the enemy, but he was not listened to. Before the battle, a sharp debate broke out in the commander’s headquarters: Publius Cornelius opposed the proposal to cross the river and ascend to the opposite steep bank, where the enemy stood. He suggested at least building a camp on this bank, where defensive positions could be taken in case of failure, but he was accused by the other tribunes of cowardice. One of his opponents “even threatened to throw down his sword if Manilius, not Scipio, commanded.”

The subsequent course of events confirmed Publius Cornelius’s fears: after crossing the river, the Romans were forced to retreat again, as Hasdrubal took up impregnable positions; the enemy counterattacked, and as a result, Manilius’s army suffered serious losses (including the deaths of three tribunes). The consequences could have been much worse if Scipio had not covered the retreat with his cavalry. However, several cohorts, losing contact with the rest of the forces, failed to cross the river and took up a circular defense on one of the hills. Livy’s epitomator writes about two cohorts, the author of the eulogy of Scipio and Pliny the Elder about three, Appian about four, and Pseudo-Aurelius Victor about eight. Some officers believed that this detachment should be left to the mercy of fate, but Publius Cornelius had a different opinion. With his cavalry, he crossed the river again, occupied one of the heights, and forced the enemy to retreat, after which he returned to his own with the lagging cohorts. For this feat, Scipio received a special military award “for saving the Roman army” — corona obsidionalis, or corona obsidionalis graminea, or corona obsidionalis aurea.

Shortly after the army’s return from the campaign to Nepheris, a Senate commission from Rome arrived at the camp. It heard praises for Publius Cornelius from the commander, the other tribunes, and the rank and file, so that “after returning, the envoys spread everywhere the fame of Scipio’s skill and luck and the attachment of the army to him.”

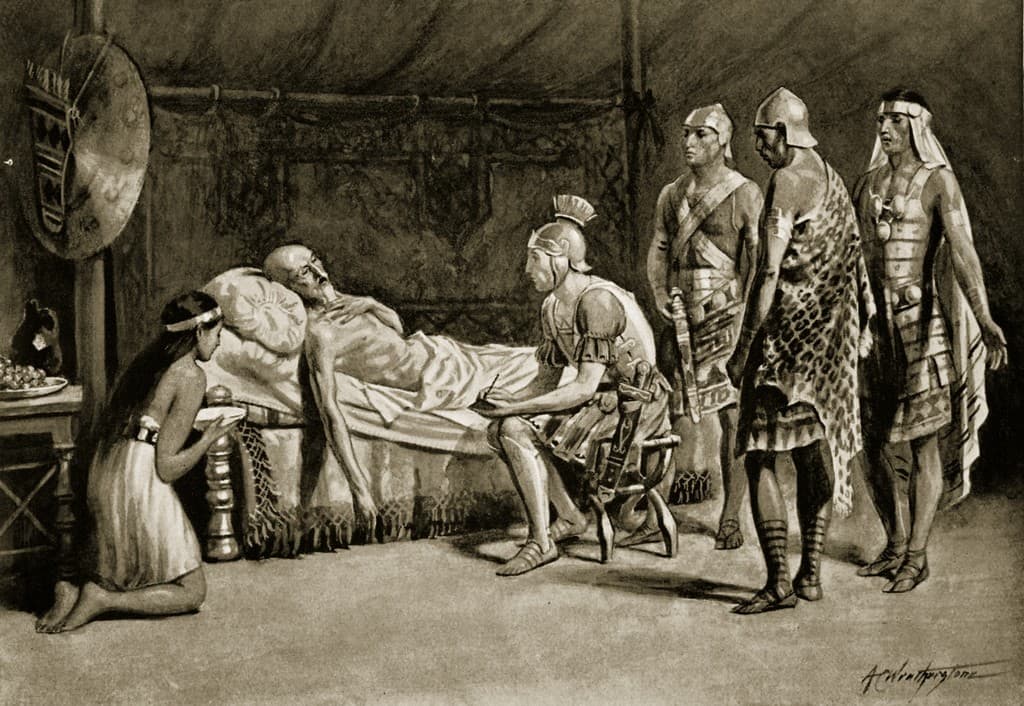

At this time (148 BC), dying Masinissa was summoned by Publius Cornelius, who wanted to consult with the grandson of his patron Scipio Africanus on the division of inheritance among his sons. Publius did not meet the king alive. But the latter, before his death, bequeathed to his numerous descendants to submit to the decision of the problem proposed by the Roman. Scipio Emiliano used this unique situation to weaken Numidia to the maximum: having distributed valuable gifts to all the illegitimate children of the deceased, he divided power among the three legitimate sons. The eldest, Micipsa, received the capital Cirta and, presumably, formal supreme power; the second, Gulussa, received control over foreign policy, and the third, Mastanabal, judicial authority.

Gulussa immediately joined the Roman army with the squadrons of the renowned Numidian cavalry. This had an impact on the course of the war: the commander of the Carthaginian cavalry, Himilco Phameas, realized the futility of further struggle and switched sides to Rome. According to Appian, there was initially a personal meeting between Phameas and Scipio Aemilianus, during which the latter guaranteed the Carthaginian’s personal safety and “gratitude.” Later, when Manius Manilius set out for Nepheris for the second time, Phameas came to him and brought with him 2200 horsemen. This became the main positive result of the campaign; it is known that Scipio again assisted his army by organizing a cavalry raid and providing soldiers with provisions. As a result, according to Appian, the Romans already began to pray for the appointment of Publius Cornelius as commander: they were confident that only this commander could take Carthage.

Manius Manilius was replaced as the head of the army by Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus. Before his departure for Rome, Manilius sent Phameas and Scipio there. The latter was greeted with enthusiasm; it is known that the elderly Cato characterized him using a verse from the “Odyssey”: “He alone is wise; all others float about like senseless shadows.”

Third Punic War: Commander

Scipio Aemilianus planned to obtain the first of the civil curule magistracies, the aedileship, in 147 BC. But news of constant defeats was coming from Africa; outraged by this, the Roman plebs became increasingly convinced that only one person could save the situation—Publius Cornelius. Therefore, when the latter appeared at the popular assembly to officially nominate himself for the aedileship, he unexpectedly found himself elected consul. The chairman of the assembly pointed out to the voters the violation of the law of Villius, according to which the candidate must be at least 42 years old (Scipio was 36 or 37), but “they insisted and demanded and shouted that by the laws of Tullius and Romulus the people are fully empowered in the elections of authorities and in recognizing or invalidating any of the laws regarding them, as they wish.” One of the plebeian tribunes threatened to stop the elections if the will of the plebs was not followed; after this, the Senate had to suspend the lex Villia for a year.

Scipio’s colleague in the consulship was the plebeian Gaius Livius Drusus, whose father was also of patrician blood, an Aemilian; according to one hypothesis, the consuls were cousins. Despite this hypothetical relationship, Drusus demanded the division of provinces by lot—apparently, he was aiming for command in Africa. But one of the plebeian tribunes achieved division through voting, and the people unanimously gave Africa to Scipio; according to another version, this decision was made by the Senate.

The new commander, in the spring of 147 BC, crossed to Utica with reinforcements for the army. He was accompanied by his cousin and brother-in-law Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, Gaius Fannius, and Polybius. In Utica, Scipio learned that the detachment of Lucius Hostilius Mancinus, which had broken through to the streets of Carthage from the sea side, was pushed back to the wall and was about to be destroyed; the next morning, Scipio set off by ships to help, arrived at a critical moment, and evacuated Mancinus’s warriors.

Upon taking command, Publius Cornelius began with strengthening discipline: he did not hope to “ever defeat enemies if he does not defeat his own warriors,” accustomed under the command of Piso to “laziness, greed, and plunder.” Scipio expelled the camp followers and other merchants from the camp, made the soldiers get rid of unnecessary luxury items, forbade them from unauthorized absences and forays for loot, instilled in subordinates “a saving fear.” Unlike his predecessors, he concentrated all his forces against Carthage, without being distracted by other cities in Africa.

The first test of strength was the night attack on Megara, the northeastern suburb of Carthage. The Romans were repelled from the walls but managed to occupy a nearby tower belonging to a private individual, and from there, they crossed over to the city fortifications via a constructed bridge. A four-thousand-strong detachment burst into Megara, and panic broke out in the city: defenders fled to Birsa. But Scipio did not pursue further success. Fearing that his legions would suffer unreasonably high losses in battles in this part of the city, cut up by hedges and canals, he ordered a retreat.

After these events, the enemy army under the command of Hasdrubal took refuge in the city. Publius Cornelius occupied and burned the enemy’s outer camp and dug a passage connecting Carthage with the mainland with two ditches, each 25 stadia long. These ditches were connected by two transverse ditches, forming a quadrangle with the Roman camp in the center. As a result, the besieged could no longer receive help and supplies from the land side; famine began in the city. To block Carthage from the sea as well, the Romans built a dam closing the harbor. But the defenders of the city managed to dig a new exit from the harbor and through it launched a whole fleet consisting of 50 ships. This came as a complete surprise to Scipio. Nevertheless, in a fierce naval battle, the Romans emerged victorious, and afterwards, they managed to occupy the mole near the entrance to the harbor. The Carthaginians recaptured the mole the same night, and full-fledged panic broke out in the ranks of the Roman army, so Publius Cornelius, who personally participated in repelling the attack, had to order the killing of fleeing soldiers. In the end, the Romans won the battles for the mole, building a brick wall here and organizing continuous shelling of the city. After that, there was a lull in active operations under Carthage, lasting from the summer of 147 to the spring of 146 BC.

At the end of 147 BC, Scipio concentrated his efforts on the last centers of resistance outside Carthage. First, Nepheris and the nearby army camp commanded by Diogenes were attacked. The assault on the camp was led by the consul himself. A complete victory was won here, and according to Appian, 70 thousand Carthaginians perished, and another 10 thousand were captured. After this, the Romans took Nepheris; the remaining cities of Libya surrendered, leaving Carthage alone.

Presumably, it was at this stage of the war that Hasdrubal offered the Romans the capitulation of Carthage in exchange for mercy for the citizens. Scipio listened to this offer, relayed to him through Gulus, with laughter, but since his consulship was ending, and his successor could claim all the glory of victory, he sought to seize the only chance: he offered Hasdrubal personal safety and the opportunity to take 10 talents of silver with him in exchange for surrendering the city unconditionally. Hasdrubal refused.

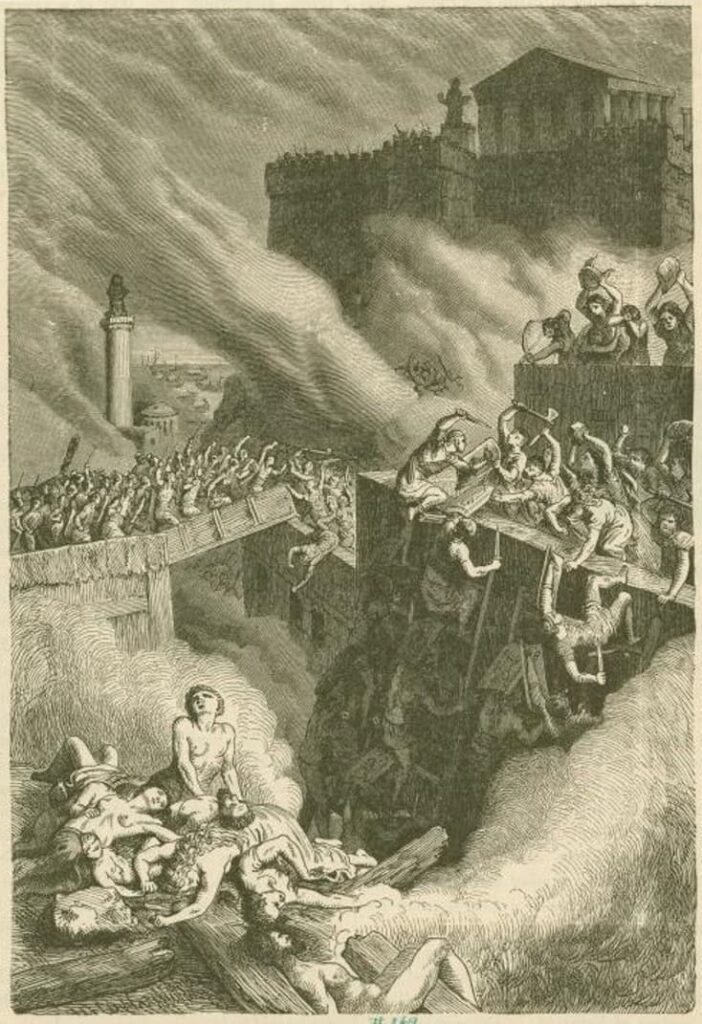

Scipio’s successor was not sent to him: the assembly prolonged his powers for the next year, 146 BC. In the spring, decisive battles for Carthage began. The Romans managed to capture the harbor of Cothon and the adjacent area; then they began a systematic advance along three narrow streets leading from this square to Byrsa. These streets were lined with six-story houses. The Romans moved both along the streets and from house to house, throwing beams and planks between windows and roofs. “There was a chorus of groans, cries, shouts, and all kinds of sufferings, as some were killed in hand-to-hand combat, others, still alive, were thrown down from the roofs to the ground, and some fell directly onto raised spears, all sorts of pikes, or swords.” Arriving at the scene of this battle and assessing the situation, Scipio Aemilianus ordered the houses to be set on fire and the path to be cleared following the fire.

And here was presented a spectacle of other horrors, as the fire burned everything and spread from house to house, and the warriors gradually demolished the houses, but, piling with all their might, they brought them down whole. This caused even greater turmoil, and along with the stones, the dead and the living fell into the middle of the street, mostly the elderly, children, and women who hid in the secret places of the houses; some of them, wounded, others half-burnt, emitted desperate cries. Others, thrown and falling from such a height along with the stones and burning beams, broke their arms and legs and were dashed to death. But this was not the end of their torment; the soldiers, clearing the streets of stones, with axes, hatchets, and hooks removed the fallen and cleared the way for passing troops; some of them with axes and hatchets, others with the points of hooks threw both the dead and the still living into pits, dragging them like logs and stones, or overturning them with iron tools: the human body was trash, filling the trenches. Some of those dragged fell headlong and their limbs, protruding from the ground, writhed in convulsions for a long time; others fell feet first, and their heads protruded above the ground, so that the horses, passing by, crushed their faces and skulls, not because the riders wanted it, but because of the hurry, as even the stone clearers did this not of their own free will; but the difficulty of the war and the anticipation of imminent victory, the haste in the movement of troops, the cries of the heralds, the noise from the trumpet signals, the tribunes and centurions with their detachments, replacing each other and passing by quickly, all this, due to haste, made everyone insane and indifferent to what they saw.

— Appian. Roman History, Punic Wars, 128.

This lasted for seven days. Roman units constantly relieved each other, and Publius Cornelius remained on the battlefield without sleep or rest. Finally, on the seventh day, the priests of the temple of Eschmoun came to him with a request to grant life to all who wanted to leave Byrsa. Scipio agreed. According to Appian, 50 thousand people took advantage of this, according to Orosius, 55 thousand (30 thousand men and 25 thousand women), according to Florus — 36 thousand warriors. Only 900 Roman deserters remained in the temple of Eschmoun, standing on a sheer cliff, and with them — Hasdrubal, his wife, and two children. The defenders of the temple could not hold out for long because they had no food. They left the outer fence and moved into the building, and Hasdrubal, abandoning his family, came to the Romans. Scipio seated him at his feet; the deserters, seeing this, showered Hasdrubal “with all sorts of abuse and reproaches” and set fire to the temple. Their death in the fire meant the fall of Carthage.

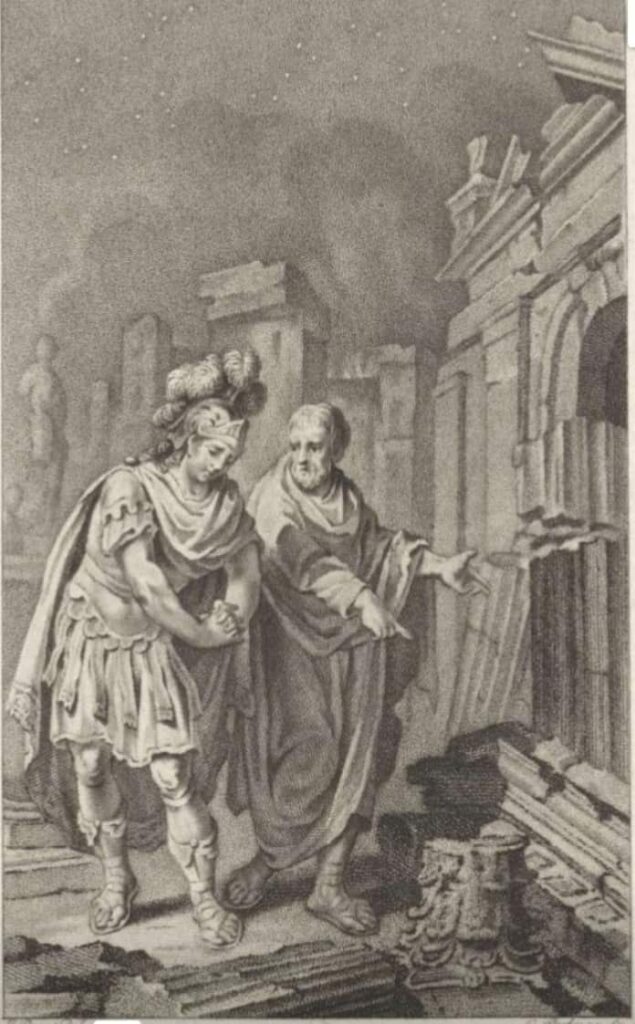

The city burned for 17 days. Polybius reports that Scipio Aemilianus, who watched the grand fire, wept with pity for the doomed city. The proconsul quoted the Iliad:

One day it will perish, the holy Troy will perish,

— Polybius. Universal History, XXXIX, 5, 1.

With it will perish Priam and the people of spear-wielding Priam.

To Polybius, Publius Cornelius said, “I am tormented by fear at the thought that someday someone else will bring such news about my homeland.”

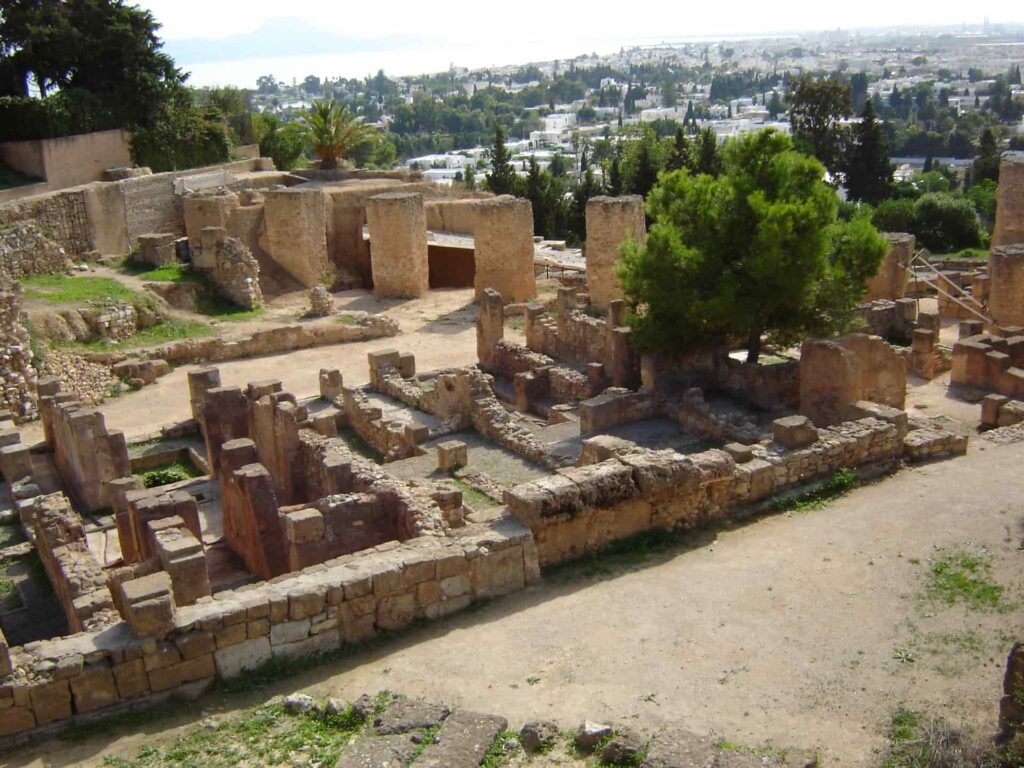

In Rome, Scipio Aemilianus’s laconic message about the long-awaited victory (“Carthage is taken, awaiting your orders”) caused general rejoicing. A special senate commission was sent, which together with the proconsul organized a new Roman province — Africa. The place where Carthage stood was cursed, plowed, and sown with salt, and settling on it was prohibited; other cities that fought against Rome were also destroyed, and their lands were distributed among Roman allies. In honor of his victory, Scipio offered sacrifices to Mars and Minerva and organized games, during which he handed over deserters and deserters to be torn apart by wild beasts.

Upon returning to Rome at the end of 146 BC, Publius Cornelius celebrated a splendid triumph, almost coinciding in time with the triumph of Quintus Caecilius Metellus over the Macedonians and Lucius Mummius over the Achaeans. According to Appian, this was “the most brilliant of all triumphs ever with a large amount of gold, statues, and temple offerings, which the Carthaginians brought from all over the world to Libya over a long period and with constant victories.” The honorary title African was now added to Scipio’s name, which his grandfather once bore.

Peak of Career

After the capture of Carthage, Publius Cornelius became one of the most authoritative politicians in Rome. He enjoyed the love of the people, was popular among the knights; around him formed an influential senatorial “faction”, to which belonged, in particular, three consuls out of ten for the first post-war five-year period. However, Scipio Aemilianus did not become the most powerful man in the republic, as was the case with his adoptive grandfather in the 190s BCE: his military glory was not as unique, and in the Senate, there was a party hostile to him, led by the brothers Cepiones (Quintus and Gnaeus), Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus, Appius Claudius Pulcher. Therefore, even one of the consuls in 145 BCE, immediately after the triumph, was elected Lucius Hostilius Mancinus, who challenged Scipio’s fame as the conqueror of Carthage.

Publius Cornelius’s enemy until his death was Metellus Macedonicus, although sources emphasize the purely political nature of the disagreements between these two nobles. According to Valerius Maximus, “their disagreements, stemming from rivalry in achievements, led to a serious feud, widely known”.

This enmity found its expression, in particular, in two episodes related to Lucius Aurelius Cotta, consul in 144 BCE and a political ally of Metellus. During the consulship, both Cotta and his colleague Servius Sulpicius Galba claimed command in Farther Spain in the war against Viriathus. Opinions in the Senate on this issue were divided, and then they turned to Scipio Aemilianus, who stated: “I think it is not worth sending either of them there, because the former has nothing, and the latter will not be satisfied with anything”. As a result, the powers of the current proconsul – Quintus Fabius Maximus Aemilianus, brother of Scipio – were extended. Later, Publius Cornelius brought Lucius Aurelius to trial on charges of extortion; Metellus Macedonicus defended Cotta and secured his acquittal. For their part, Quintus Caecilius, Lucius Caecilius Metellus Calvus, and the two Cepiones united against Quintus Pompeius, who was once part of Scipio Aemilianus’s circle, and accused him of bribery. Pompeius was also acquitted; in both cases, sources cite the reason for such a decision by the judges as their desire to show that the authority of the accuser cannot influence the outcome of the trial. It is also known that Metellus Macedonicus was a “zealous enemy” of Lucius Furius Philus, Publius Cornelius’s closest friend.

In 142 BCE, Scipio Aemilianus nominated himself for the position of censor. His competitor was Appius Claudius Pulcher. Publius Cornelius won thanks to his popularity among the people, although he refused traditional campaign methods; in particular, he did not greet voters by name, as was customary. Scipio’s colleague in the censorship was another recent triumphator, Lucius Mummius Achaicus, and such a choice of colleagues all sources call extremely unsuccessful. Mummius and Cornelius were very different people with different political interests; the former was inclined to compromise, especially in relations with the nobility, while the latter, an implacable enemy of the aristocratic “party” of the Claudii, intended to fight against the “vices” in the manner of Cato the Censor. Scipio Aemilianus’s attitude towards Lucius Mummius is characterized by his phrase, spoken either in the Senate or at a popular assembly: “What my colleague has or has not given me is indifferent!”

Several examples of “moral judgment” by Publius Cornelius as censor are preserved in the sources. Scipio enrolled Tiberius Claudius Asellus in the aerarium (the lowest class) for insubordination; deprived a young knight of his horse for mocking military valor (during the Third Punic War, he organized a feast at which a honey cake called “Carthage” was served); censured Publius Sulpicius Gallus for frivolous clothing (he wore a tunic with sleeves). Publius Cornelius caught Gaius Licinius Sacerdos in perjury, but did not punish him, as he found no other witnesses. There were other numerous reprimands. Lucius Mummius repealed some of his colleague’s orders – in particular, sanctions against Asellus, and this, according to the prevailing opinion at the time, brought the wrath of the gods upon the Republic. Scipio Aemilianus did not hide his contemptuous attitude towards Mummius. This was manifested, in particular, in the fact that the latter was not invited to the celebratory dinner in honor of the consecration of the temple of Hercules; contemporaries condemned Scipio for such open disregard for his colleague.

Together with Mummius, Publius Cornelius built a bridge across the Tiber (Pons Aemilius), continued to adorn the Capitol temples. During the census conducted by the censors, 328,442 citizens were counted. Concluding the lustrum (solemn sacrifice), Scipio Aemilianus pronounced a new prayer, created by him: he did not ask the gods to increase the wealth of the Roman people but wished to preserve what already exists. This text, fixing Scipio’s uncertainty about Rome’s happy future, was used by all subsequent censors.

Immediately after the censorship, Publius Cornelius was brought to trial by Azellus, who held the position of plebeian tribune (140 BCE). The content of the lawsuit is unknown; the trial lasted for at least five sessions and ended in Scipio’s acquittal. To subsequent times belongs Publius Cornelius’s participation in a diplomatic mission to the Eastern Mediterranean. Together with Lucius Caecilius Metellus Calvus and Spurius Mummius, he visited Egypt, Syria, Asia, Cyprus, and Greece, in all these regions restoring old connections and strengthening alliances. Contemporaries noted the envoys’ simple manners and friendliness. There are no exact dates in the sources, but since in Pergamon the envoys were received by King Attalus II, who died in 138 BCE, this date is the latest possible.

In his domestic political activity, Publius Cornelius stood on moderately conservative positions: for example, it is known that in 145 BC, a member of his “circle,” Gaius Lelius, failed a democratic bill on the replenishment of priestly colleges through popular vote. On the other hand, on behalf of the same Lelius, the “circle” planned to put forward legislative initiatives to improve the situation of small landowners in Italy. Only one mention of these initiatives has been preserved by Plutarch without specifying their content. There are no exact dates here: it could be during Lelius’s tribunate (151 BC), his praetorship (145 BC), or consulate (140 BC), and researchers do not have substantial evidence in favor of any of the options. Rumors of impending reforms spread widely and sparked opposition from the nobility. “Encountering fierce resistance from powerful citizens and fearing disorders,” the members of “Scipio’s circle” ceased their activity in this direction.

Upon his return from the East in 137 BC, Publius Cornelius actively participated in the development of the Cassian Law, which introduced secret voting in the centuriate assemblies, which considered major criminal cases. The adoption of this law was a serious blow to the dominance of the nobility, and therefore reformers faced strong resistance. When the plebeian tribune Antius Brizon vetoed the bill, Scipio Aemilianus persuaded him to withdraw it, and thanks to this, the law was passed. In the following several years (137-135), Publius Cornelius’s influence reached its peak; and during this period, the Numantine problem reached its utmost sharpness.

Numantine War

Starting from 143 BC, Roman governors of Hispania Citerior regularly besieged the city of the Arevaci Numantia and could not take it. In 139 BC, Quintus Pompey, by that time at odds with Scipio Aemilianus, was forced to conclude a favorable peace with the Numantines, and in 137 BC, Gaius Hostilius Mancinus, also besieging the city, was himself surrounded by the enemy and capitulated. His army left all weapons and property to the Numantines. Upon learning of this, the Senate summoned the consul to Rome to investigate all the circumstances of the case; an animated and protracted discussion ensued about what to do with Mancinus’s treaty and, in case of refusal to ratify it, what to do with the people who concluded it. Scipio Aemilianus, along with his cousin Scipio Nasica Serapion, led in the Senate the faction that advocated the annulment of the agreement and the extradition of Mancinus, his quaestor, and military tribunes to the enemy. Publius Cornelius was not even stopped by the fact that another of his first cousins and his wife’s brother-in-law, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, was the quaestor who sealed the treaty with his signature.

Researchers associate Scipio’s position with both his principled rejection of compromises in relations with still undefeated enemies and his hostility towards the Gostilii family—Gaius Mancinus was the first cousin of Lucius Mancinus, who claimed the status of the conqueror of Carthage. The consuls of 136 BC, Lucius Furius Philus and Sextus Atilius Serranus (both belonging to “Scipio’s circle”), proposed to the Senate to annul Mancinus’s treaty and hand over to the Numantines the people who signed it. Senators who sided with the two Scipios supported this initiative and turned to the people with a corresponding recommendation; the people agreed to hand over Gaius Hostilius, while Gracchus and the military tribunes were exempted from responsibility. As a result of these events, Tiberius Sempronius became an enemy of Scipio.

In the next two campaigns, the Romans continued to suffer defeats under Numantia. As a result, there was a widespread belief that only one person could end this war with victory—Scipio Aemilianus. He himself did not seek command, but the people nevertheless elected him consul in 134 BC. According to Valerius Maximus, the election took place unexpectedly for Publius Cornelius when he appeared on the Field of Mars to support his nephew, who was running for quaestorship. The Senate, faced with the fact, legalized this election retrospectively and without drawing lots granted Scipio Hispania Citerior as his province.

Subsequent events showed that the senators, among whom at that time political opponents of Scipio Aemilianus dominated, were not inclined to cooperate with the new consul. They did not allow Publius Cornelius to recruit a new army, citing the fact that there were enough troops in Hispania Citerior and that there were also wars in other provinces; moreover, the Senate refused to give Scipio money. Therefore, Publius Cornelius had to use his own means and money received from friends for the needs of the war. He set off for the Pyrenees accompanied by 4,000 volunteers, including an elite detachment of 500 people, whom Scipio called his “friends.” It is known that among the commanders were his brother Quintus Fabius Maximus Aemilianus (legate), the son of the latter Quintus Fabius Maximus, who subsequently received the agnomen Allobrogicus (quaestor), military tribunes Publius Rutilius Rufus, Sempronius Azellio, and (presumably) Gaius Sempronius Gracchus (cousin and brother-in-law of the commander), cavalryman from Arpinum Gaius Marius, Polybius, Gaius Lucilius. Auxiliary squads were provided by Rome’s vassals—King Micipsa of Numidia (this detachment was commanded by his son Jugurtha), Aetolians, Attalus III of Pergamon, Antiochus VII Sidetes.

Presumably, in April 134 BC, Publius Cornelius assumed command of the provincial army. By that time, it had been suffering defeats for several years in a row; military morale and discipline were at a very low level. According to Appian, the soldiers led “a life of idleness, full of mutinies and revelry.” The consul took measures to quickly rectify the situation: he expelled all merchants, soothsayers, prostitutes from the camp, ordered the soldiers to get rid of wagons, draft animals, and all unnecessary baggage, prohibited the use of soft bedding, and sitting on mules during marches. Sources report Scipio’s harsh criticism of the officers accustomed to useless luxury. For example, to Gaius Memmius, who brought “cooling cups adorned with stones, the work of Phyrichus” to the war, Publius Cornelius declared: “For me, you are unfit temporarily, for yourself and the state — always” (some researchers with greater or lesser confidence identify this Memmius with the plebeian tribune of 111 BC, but according to other opinions, there is no basis for this). To Gaius Caecilius Metellus (later Caprarius), the fourth son of Metellus Macedonicus, Scipio said: “If your mother bears a fifth time, she will bear a donkey!”

At the time of the consul’s arrival, his army numbered about 24,000 soldiers. With the help of Spaniards, Publius Cornelius increased its strength to 60,000 people. Initially, the commander limited himself to training his men: his goal was to accustom the soldiers to long marches and earthworks. Succeeding in this, Scipio began actions against the Vaccii, being extremely cautious at first due to the army’s low combat readiness; there are no reliable reports of any major clashes at this stage of the war in the sources. In the autumn of 134 BC, the Romans finally approached Numantia. Their goal, apparently, was initially to take the city by siege.

The Romans built two camps (in one of them, Maxim Aemilianus was the commander), a circumvallation around Numantia, and dug a moat. The defenders of the city (there were only about 4,000 of them) repeatedly tried to destroy the wall during construction, but the besiegers, thanks to their numerical superiority, repelled all such attempts. At the same time, the Numantines constantly provoked the Romans to a major battle, but Publius Cornelius ignored these provocations. This siege continued throughout the winter. Numantine Rector managed to get out and appealed for help to other cities of the Arevaci; he found sympathy only in one city, Lutia, but Scipio instantly responded to this: he ordered the hands to be cut off to 400 young people who expressed willingness to help Numantia.

The failure of Rector’s mission meant that Numantia was doomed. By summer, the city ran out of food, and hunger drove the besieged to cannibalism. In July, Numantine envoys attempted to negotiate surrender on moderate terms with Scipio, but he demanded unconditional surrender. Presumably, after this, the defenders of the city made a final sortie to die in battle; then Numantia surrendered. Many townspeople used the one-day respite granted by the Romans to commit suicide, and all others were sold into slavery. Publius Cornelius left only 50 people for his triumph. Numantia was destroyed, and its lands were divided among neighboring communities. Publius Cornelius did not wait for the Senate commission, which was supposed to establish order in the conquered territories with his assistance: after the war ended, he sailed to Italy.

Struggle with the “reform party”

While Publius Cornelius was subduing Numantia, the political struggle in Rome reached unprecedented sharpness. Scipio Aemilianus’s opponents became active immediately after his departure to Spain: Publius Mucius Scaevola became consul, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus succeeded in his election as plebeian tribune and, relying on the support of his father-in-law Appius Claudius Pulcher (the latter was the princeps of the Senate), put forward a project of agrarian reform. He proposed to limit the lease of ager publicus to 500 jugera of land or a thousand jugera with two or more adult sons. Surpluses were subject to confiscation and distribution among the poor citizens in the form of inalienable allotments, the maximum area of which could be 30 jugera. This project became law; to implement the reform, a special commission of three people (triumviri agris iudicandis assignandis) with very broad powers was created, which included Tiberius himself, Pulcher, and Gaius Gracchus, who was with Scipio’s army.

Enemies of the reforms led by another cousin of Scipio Aemilianus, Scipio Nasica Serapio, soon organized a crackdown on Tiberius Gracchus and a number of his less prominent supporters. Theoretically, Publius Cornelius and his circle could sympathize with the idea of the reform itself, but they could not approve of Tiberius Sempronius’s radical methods of political struggle; in particular, the latter deposed his colleague who vetoed his bill. Therefore, Scipio Aemilianus, upon learning of Gracchus’s death during the siege of Numantia, expressed his approval with a quote from Homer: “Thus let anyone perish who commits such a deed.”

It is unknown exactly when Publius Cornelius returned to Rome from Spain. According to G. Simon, he must have been in a hurry, knowing that the “reform party” was not defeated and that, in particular, the agrarian commission continued its work. Therefore, by November 133 BC, by the time of the consular elections, Scipio was already in Rome and ensured the election of his friend, the “new man” Publius Rupilius, as consul. According to another version, he returned only in spring or summer 132 BC.

The Senate granted Scipio the right to a triumph and another honorary title — Numantine (Numantinus). The triumph turned out to be quite modest since there was no rich booty captured in the war; Publius Cornelius’ soldiers received only 7 denarii each, about 4 times less than usual in such cases. Soon after, the first confrontation between Scipio and the reformers occurred. Either Gaius Sempronius Gracchus and Marcus Fulvius Flaccus or Gaius Papirius Carbo asked the recent triumphator in the popular assembly what he thought about the death of Tiberius Gracchus. The purpose of the question, according to historians, was to “drive a wedge between the people and their beloved hero,” that is, Publius Cornelius. The latter replied that “if Gracchus intended to seize the state, then he was rightfully killed.” Upon hearing this, the people shouted in outrage; then Scipio Aemilianus declared, “I was not frightened by the cry of armed enemies, should I be frightened by you, to whom Italy is a stepmother?”

As a result of these events, Publius Cornelius lost his popularity among the plebeians. This became evident in 131 BCE when a commander was needed for the Pergamene War; Scipio’s candidacy, put forward as an alternative to the consuls of that year, received votes from only two tribunes, and Publius Licinius Crassus Mucianus, the father-in-law of Gaius Gracchus, was sent to war. Nevertheless, Scipio retained some influence over the people: when Carbo proposed a bill allowing the re-election of tribunes of the plebs (in 131 or 130 BCE), Publius Cornelius opposed this initiative, supported by Gaius Gracchus, and his opinion prevailed.

Plutarch on the enmity between Scipio Aemilianus and Gaius Gracchus:

“The followers of Gaius cried out: ‘Death to the tyrant!’ Scipio said: ‘It is right that whoever wages war on his country should want my death, for as long as Scipio stands, Rome shall not fall, nor shall Scipio live when Rome falls.'”

With this victory, a new phase of political struggle began for Scipio, in which his main opponent became Gaius Gracchus. All the enemies of reform among the senators and wealthy landowners rallied around Publius Cornelius. The agrarian commission began to confiscate excess public lands from the allies, and numerous complaints from Italian landowners began to reach the senate and Scipio personally. The latter used this to convince the senate to curtail the powers of the commission. From now on, the triumvirs could not adjudicate disputed issues, deciding which land was private property and which belonged to ager publicus. This became the prerogative of the consuls, who in turn effectively distanced themselves from the problem. As a result, in 129 BCE, the agrarian reform was effectively rolled back.

Publius Cornelius planned to continue his fight against the reformers. Rumors circulated in Rome about his imminent appointment as dictator, and Scipio’s enemies used this to claim that he intended to annul Gracchus’ law and “start an armed slaughter.” Publius Cornelius, in response, said there was a danger to his life.

Death

Gaius Lelius the Wise on the death of Scipio Aemilianus:

“…His life was such that there was nothing to add to it — neither in terms of luck nor in terms of glory — and it was freed from the sense of impending death by its suddenness. It is difficult to speak of this kind of death; what people suspect, you know. Nevertheless, it is permissible to say with confidence one thing: of all the days crowned with glory and bringing him joy that he experienced in life, the brightest was the one when, after the senate meeting, fathers of the senate, the Roman people, allies, and Latins accompanied him home in the evening; on the eve of his departure from life: from such a high degree of honor, it seemed as if he moved to the gods, not to the underworld.”

In April or May of 129 BCE, on the morning of the day when Publius Cornelius was supposed to deliver another speech in the popular assembly, he was found dead in his bed. The day before, he was healthy; next to the body lay a wax tablet on which the outline of the speech was to appear. The suddenness of this death led to rumors of murder; it was said that traces of strangulation remained on the deceased’s neck, and Gaius Gracchus, Flaccus, Carbo, and even Scipio’s wife and mother-in-law were accused of poisoning him. According to Valerius Maximus, Metellus Macedonicus was sure that Publius Cornelius had been killed; ten years later, Lucius Licinius Crassus named Carbo as a participant in this crime, who had to take his own life.

According to another version, Scipio committed suicide, “feeling that he would not be able to keep his promises.” Finally, some claimed that he was strangled by some foreigners who broke into the house at night. However, no investigation was conducted, and Gaius Lelius insisted that the death was natural. A century and a half later, Gaius Velleius Paterculus wrote that the death of Scipio Aemilianus was considered violent only by “some.”

Despite his merits, Publius Cornelius was not honored with a state funeral. Nevertheless, the funeral took place amidst universal mourning; all four sons of Metellus Macedonicus — Quintus (later Balearicus), Lucius Diadumenus, Marcus, and Gaius, who participated in the Numantine War, took part in the procession carrying the body. They were directed to the funeral by their father, who forgot about his former enmity with the deceased. The traditional eulogy was delivered by Scipio’s closest relative — his nephew Quintus Fabius Maximus (Maximus Aemilianus was already deceased by then); the orator thanked the gods that Publius Cornelius was born in Rome. However, Cicero reports that the speech written by Gaius Lelius was delivered by another nephew of the deceased, Quintus Aelius Tubero, but historians believe that Cicero was mistaken in this case. It fell to Tubero to organize a feast for the people; being a fervent adherent of Stoic philosophy, he tried to arrange a feast in the spirit of “ancient simplicity.” According to Cicero, “this most learned man and a Stoic laid out some goat skins on wretched Punic couches and set out Samian pottery, as if the Cynic Diogenes had died, and not a celebration was held in memory of the divine Publius Africanus.” This cost Tubero his career: later, the people, outraged by the dissonance between the greatness of the deceased Scipio and the poverty of the memorial service, refused Quintus Aelius the praetorship.

Publius Cornelius’ body was buried not in the Scipio family tomb near the Capene Gate but somewhere else — possibly, near the body of Paulus Macedonicus.

Scipio Aemilianus as an Orator

Cicero considers Publius Cornelius one of the two best orators of his time, alongside Gaius Laelius. “However, Laelius’ oratorical fame was brighter.” At the same time, according to Cicero, both had a “old-fashioned and unpolished” style. According to Aulus Gellius, Scipio “spoke the most purely of all his contemporaries.”

Sources mention “numerous speeches” by Scipio Aemilianus. There is mention of a speech against Gaius Papirius Carbo, issued after it was delivered; Cicero in his treatise “On Friendship” speaks of this speech, saying that it was “in everyone’s hands.” A fragment of the speech “Against the Judicial Law of Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus” has been preserved in Macrobius’ “Saturnalia,” in which the orator speaks out against the widespread fascination of aristocratic youth with dances. Aulus Gellius quotes the fifth speech of Scipio against Tiberius Azellus, another speech against this tribune without indicating the ordinal number, and a speech “On Morals,” delivered during the censorship.

Personality

Publius Cornelius was of short stature. T. Bobrovnikova suggests that he had a fragile build, but this was combined with iron health, endurance, and energy. He shaved his beard constantly until at least the age of 40; according to Pliny the Elder, it was Scipio Aemilianus who popularized daily shaving. At the same time, he condemned men’s excessive attention to their appearance, so shaving was a manifestation of his strict self-discipline. Scipio was characterized by modesty, respect for those below him in rank and origin, and a clear understanding of subordination. His ambition “from the first steps of his career took the form of zealous duty fulfillment.” As an officer, he demonstrated foresight, the ability to act according to a preconceived plan; but if the situation got out of control, he could instantly assess the situation and take desperate measures that invariably led to success.

Publius Cornelius was characterized by integrity and keeping his word, even if that word was given to an enemy. He always remained in control of himself, not giving in to anger or other emotional outbursts. For all these virtues, he enjoyed the love and respect of soldiers and the people.

As a military leader, Scipio Aemilianus relied on the experience of his native father. In particular, according to Sempronius Azellio, Publius “heard his father Lucius Aemilius Paullus say that a good commander will not engage in open battle unless extreme necessity arises or a very convenient opportunity presents itself.” Other authors attribute this maxim to Scipio Aemilianus himself.

Ancient authors emphasize the selflessness of Publius Cornelius: having taken Carthage and given his soldiers the richest booty, he took nothing for himself and even forbade his slaves and freedmen from taking or buying anything. According to Plutarch, Scipio throughout his life “bought nothing, sold nothing, and accumulated nothing in the house; and after him, there remained only 33 pounds of silver and 2 pounds of gold.” In addition to generosity in the division of inheritance among relatives, Publius was characterized by generosity in everyday life. This is confirmed by the story told by Macrobius: once receiving a rare red fish as a gift, Scipio Aemilianus began to invite people to dinner who had come to greet him that day; eventually, his friend Pontius felt compelled to whisper in his ear: “Think, Scipio, about what you’re doing. Such red fish is rare for few people.”

Assessments

In sources

Scipio Aemilianus received the highest praise in the works of ancient authors. According to N. Trukhina, “we only hear insignificant reproaches in irony, ambition, proud treatment of Lucius Mummius.” Already friends of Publius Cornelius considered him “the ideal of a man and a citizen.” Gaius Lucilius in one of his poems calls him “the Great Scipiade,” Gaius Fannius in Cicero’s treatise “On Friendship” says that “there was no better, no more famous man than Publius Africanus,” Gaius Laelius notes that “the greatest hopes” that his fellow citizens associated with Scipio, were fully realized.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, born 23 years after the death of Publius Cornelius, admired him and many people from his environment. The middle of the 2nd century BC appeared to Cicero as the “golden age” of the Roman Republic, when the first genuine orators lived (and among them was Scipio Aemilianus), when the influence of philosophy on Roman society was spreading. Since Marcus Tullius held conservative views from a certain point, he approvingly spoke of Scipio’s struggle against the Gracchans; he also highly appreciated the activities of the “Scipio circle” in the cultural field. Cicero received information about Publius Cornelius from eyewitnesses — Laelia Major and Publius Rutilius Rufus; besides, he had close relations with the philosopher Posidonius, a disciple of Panaetius.

Scipio Aemilianus acts or is often mentioned in a number of Cicero’s treatises. The action of the dialogue “On Friendship” takes place in 129 BC, a few days after the death of Publius Cornelius. In it, Gaius Laelius speaks with his sons-in-law, Gaius Fannius and Quintus Mucius Scaevola Augur, and one of the important topics is the relationship between Laelius and the deceased Scipio. In the treatise “On Old Age,” Publius Cornelius and Laelius speak with Cato the Censor, who explains to them why he reconciles so easily with his advanced age. In the dialogue “On the State,” Scipio Aemilianus is the main character: shortly before his death, he talks with friends about various types of government. This treatise concludes with a kind of apotheosis “The Dream of Scipio,” in which Publius Cornelius sees his adoptive grandfather in a dream. He predicts a great future for his grandson.

Ancient historians of subsequent epochs spoke of Scipio Aemilianus with great respect. Thus, Gaius Velleius Paterculus calls him “thanks to his talent and education the most outstanding man of his century in matters of war and peace, not having done anything in his life that would not be worthy of praise — neither in words, nor in deeds, nor in thoughts.” For Diodorus Siculus, he is “the greatest man of his time.” Plutarch wrote a biography of Publius Cornelius paired with the biography of Epaminondas, but both texts have not survived; according to Plutarch, Scipio “far surpassed all his contemporary Romans in valor and power without exception.”

Nevertheless, some ancient authors consider Scipio’s capture of Carthage as the end of the “golden age” of the Roman Republic: in their view, Carthage was a kind of “whetstone” that gave shine and sharpness to the Roman sword. Only fear of the old enemy prevented the Romans from “transitioning from virtues to vices” until the 140s BC.

In historiography

The fragmentary nature of the sources does not allow historians to come to a consensus on the political activities of Scipio Aemilianus. There are polarized assessments: Publius Cornelius is described as a military man uninterested in politics or as an ambitious individual who stopped at nothing to expand his influence within the state. According to researcher A. Estin, Publius Cornelius represented a new type of populare: leading one of the senatorial factions fighting for positions and honors, he actively used the popular assembly in this struggle, involving it in high politics and “corrupting” it. At the same time, Scipio had no original political course.

According to T. Mommsen, Publius Cornelius, more than anyone else of his contemporaries, was suited to the role of reformer in conditions when Rome urgently needed transformations. “But he was convinced that the country could only be saved at the cost of… revolution… He thought that such a remedy was worse than the disease itself.” Therefore, Scipio did not join either the conservatives or the Gracchans and remained alone, but after his death, both “parties” claimed him as “theirs.”

Some researchers place the agrarian reform plan developed by the “Scipio circle” on a par with the reforms of Tiberius Gracchus, since the goal in both cases was the revival of small peasantry and the preservation of Rome’s polis structure; accordingly, it was a conservative program. H. Scullard even suggests that it was Publius Cornelius who created the political program that Gracchus later attempted to implement. In the context of this hypothesis, the “Scipio circle” is attributed to the camp of moderate reformers; its initial conservatism could have been strengthened by the radical methods of Tiberius Gracchus. Guided by the ancient system of values and the idea of the inherent superiority of the nobility, Scipio was able to reject a series of laws proposed by the populares, which threatened the penetration of the plebs into the priestly colleges and the strengthening of the power of plebeian magistrates, and succeeded in reversing the Gracchan reforms, which was in the interests not only of large but also of medium land ownership.

In 2001, the only biography of Scipio Aemilianus in Russian was published, written by T. Bobrovnikova. According to A. Korolenkov, it “is not devoid of elements of fictionalization and is extremely tendentious.”

In culture