- The sea monk myth originated in 12th-century writings.

- Sea monk sightings linked to octopus and monkfish theories.

- Conrad Gessner “discovered” sea monk species in 1550.

- The sea monk myth was probably associated with anti-Catholic sentiments.

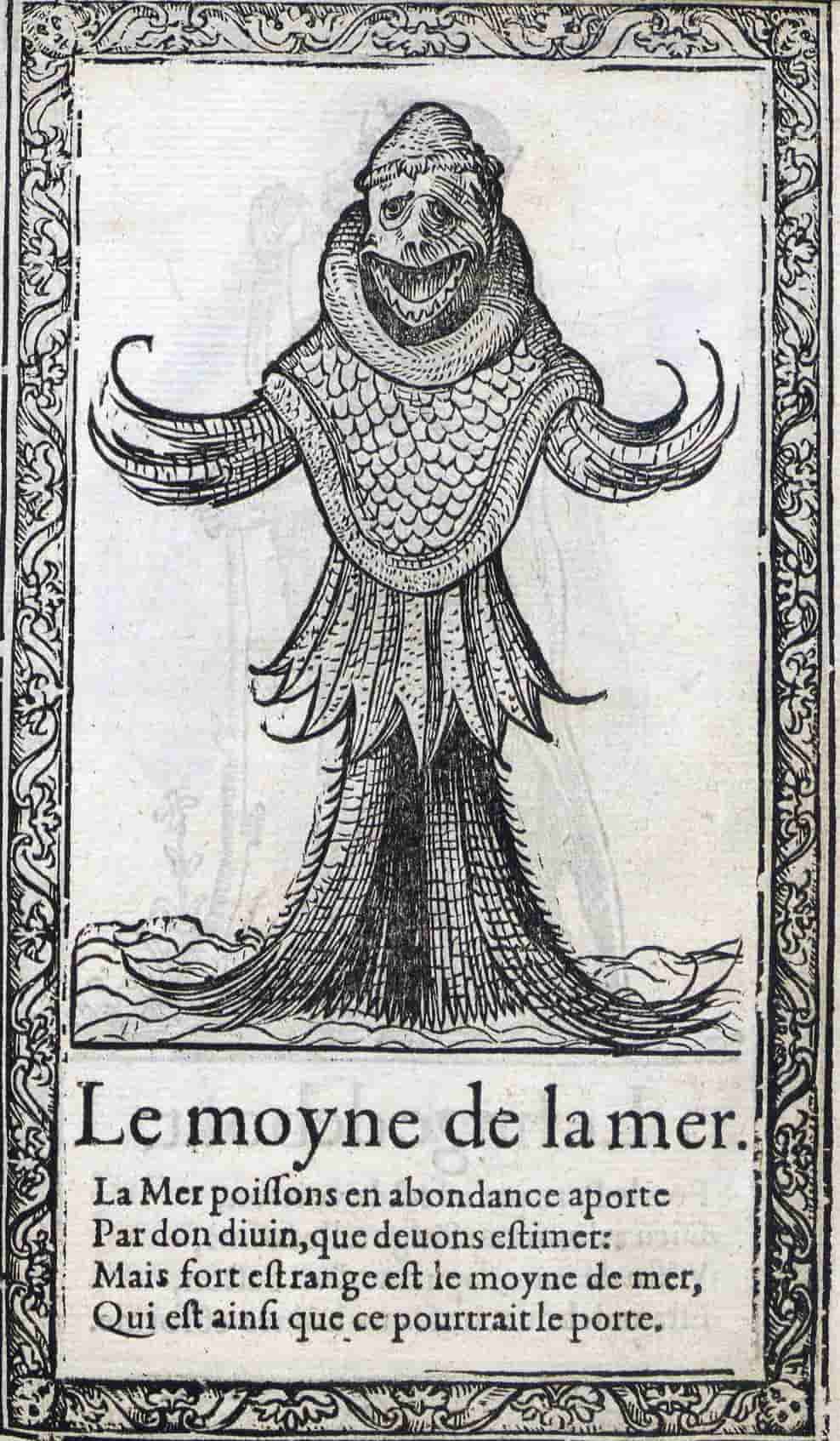

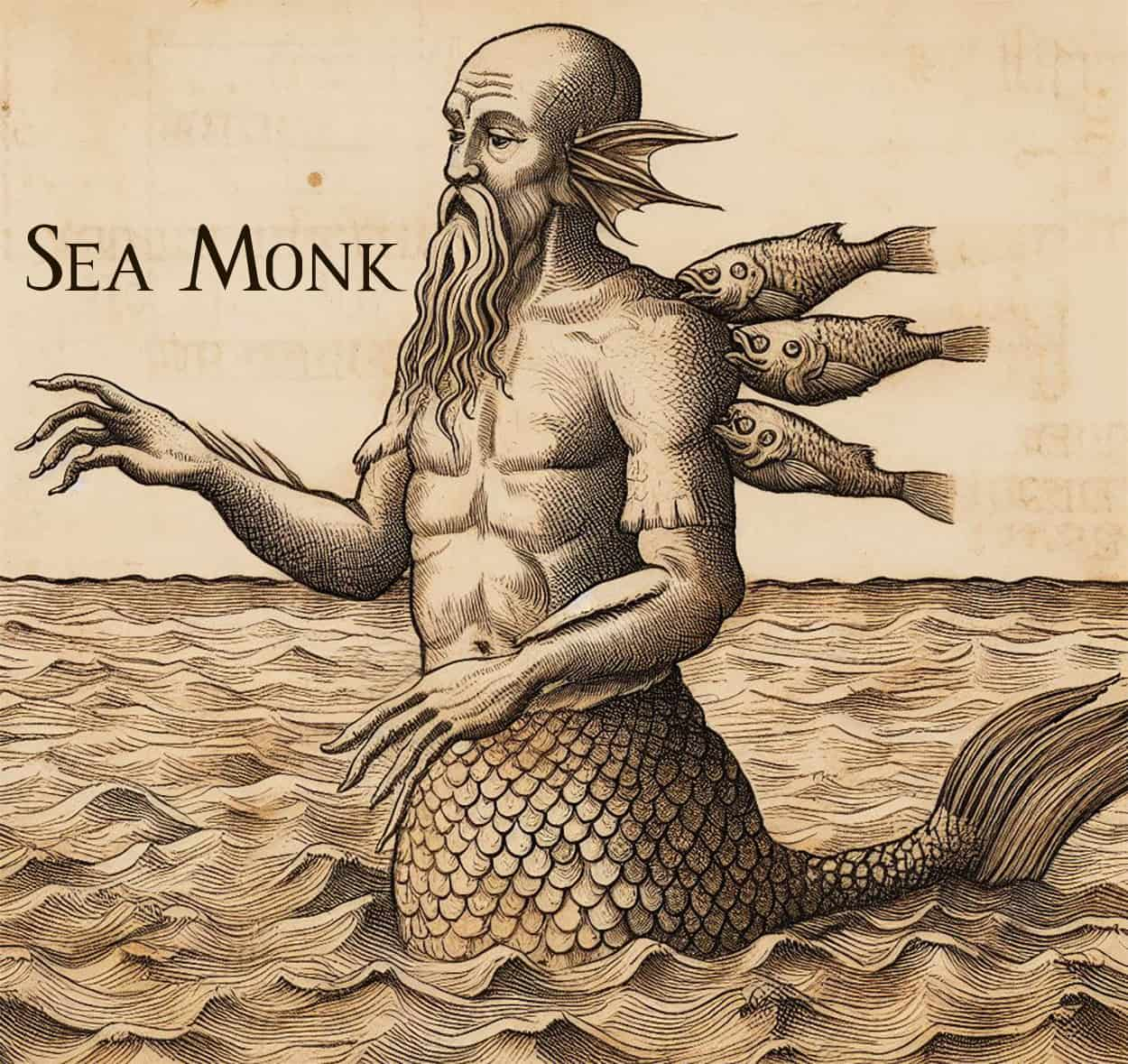

The sea monk (piscis monachus) is a made-up beast popularized in early modern and medieval animal tomes. Around the year 1200, he was introduced to the world by Alexander Neckam. There have been several reports of sightings of the sea monk since 1550; one specimen was even supposedly given to the King of Denmark. Illustrations of the sea monk may be found in many writings of the 16th century, for example in Conrad Gessner‘s Fish Book. Sightings of the sea monk in contemporary times have been tried to be explained away as misidentifications of different creatures. Though it was first attributed to an octopus by Japetus Steenstrup in 1855, subsequent speculation has focused on other potential marine mammals such as seals, angelsharks, and anglerfish.

Their Symbolic Meaning

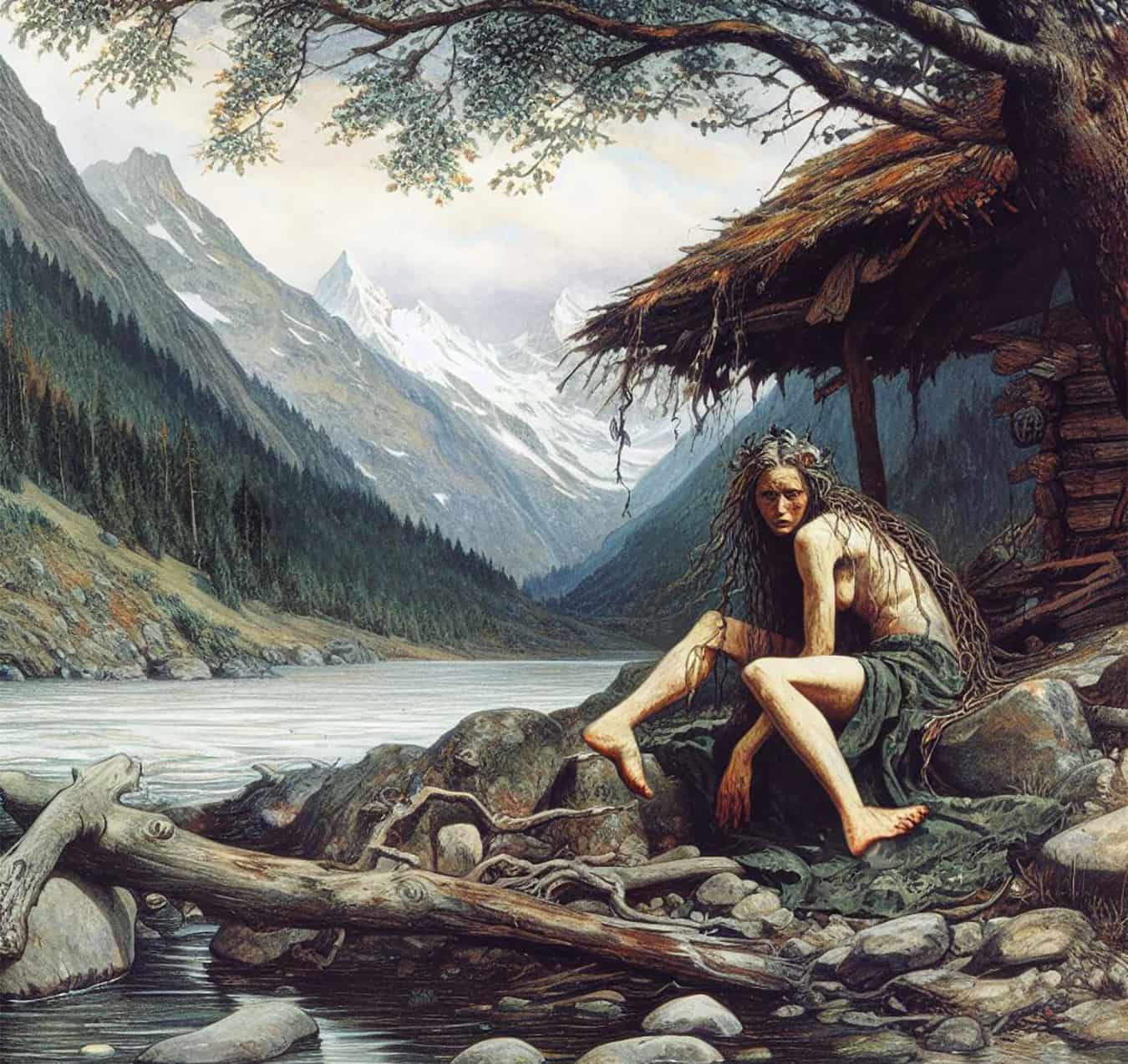

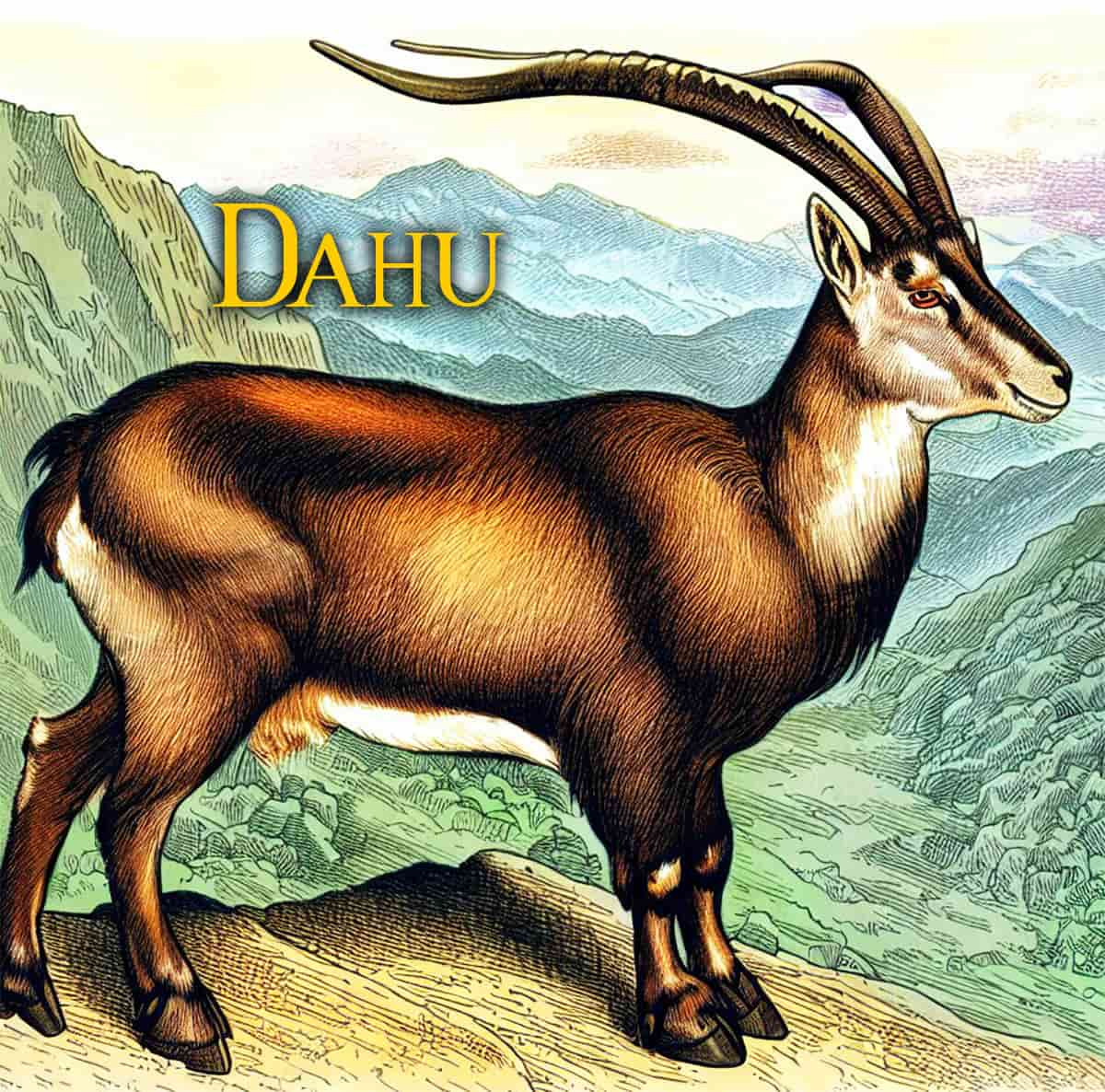

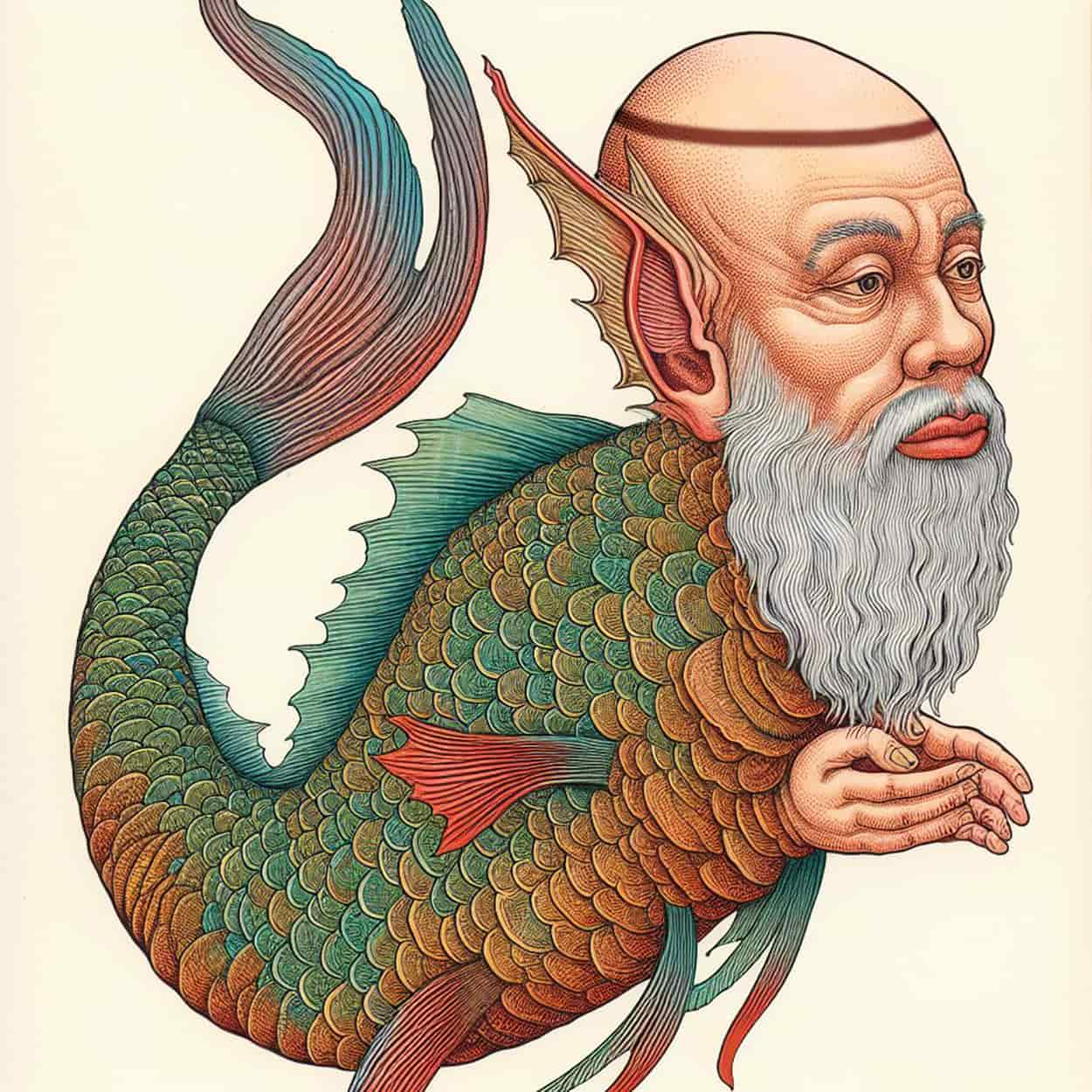

Bestiaries from the time period often portrayed him as a scaly, lanky, purple creature with humanoid characteristics. It was said to be eight feet in length, and its corollated head gave it a monkish appearance.

At the time, the sea monk was hailed as a prodigy, a marine monster that proved the universe was “perfectly balanced.” It testified to the singular symmetry of the world, whereby everything terrestrial has an equivalent in the sea.

Just as Lucas Cranach portrayed the “Donkey Pope” and the “Monk’s Calf,” these alterations, including the origin of sea monks, could have been driven by anti-Catholic sentiments.

Origins of the Sea Monks

The first written reference to a “sea monk” dates back to the late 12th or early 13th century, to a book by Alexander Neckam titled “On the Natures of Things”. Strange fishes are discussed in this book, and it is said that some fishes resemble monks. An expanded version of this story may be found in Albertus Magnus’ “On Animals” where the first sightings in the British Sea are also recounted. Thomas of Cantimpre, a student of Albertus, wrote about the sea monk in his work “A Book on the Natures of Things.”

Their Appearance

In his Book of Nature, a German translation of Cantimpre’s work, Conrad von Megenberg introduces the sea monk to the German-speaking world. You may find the sea monks on this list along with other “sea marvels” like sea dragons and sea cattle. Megenberg claims that the sea monk has a fish’s snout and a countenance unlike that of a human, but that the sea monk’s head resembles a monk’s tonsure.

This is the description of an exceptional “fish” by Megenberg in 1349:

Monachus marinus. The monachus marinus is a monster in the shape of a fish, and the top like a man; it has a head like a newly tonsured monk. It has scales on its head, and around its head is a black hoop above the ears; the hoop is composed of hair like that of a true monk. The monster is in the habit of luring people to the seashore by making various leaps, and when he sees that people are happy to look at his game, he is even more cheerful to rush in different directions; when he can grab a man, he drags him into the water and devours him. It has a face not quite similar to a man: fish nose and a mouth very close to the nose.

— Conrad von Megenberg, Book of Nature, 1349

The sea monks would lure people with their playful antics, only to drag them beneath the ocean and devour them. This is similar to the legend of the mermaids. This theory holds that Megenberg’s descriptions of the “marvels” of the water are allegories of human attitudes, character qualities, or professions, making the sea monk a metaphor for a charismatic con artist who leads his victims astray.

Sea Monk Sightings in History

There are reports of sea monk sightings from the Middle Ages to the early modern era. One sea monk was supposedly seized in 1187 in Suffolk and kept for six months in a fortress. But he jumped into the water to escape when the conditions were right. There have also been reports of sightings in the open seas of the North Sea and along the Norwegian coast.

In the year 1531, a “sea monk” was hauled up in nets not far from the Swedish city of Malmö. Boethius’ account of a similar creature in the Firth of Forth in Scotland was cited, as was a 1531 sighting off the coast of Poland.

According to Arild Huitfeldt’s chronicle of the Danish kingdom, he fell victim to the net once again in Denmark. In 1546, a monstrous fish that resembled “a monk with a shaved tonsure in his hood” washed up on the Danish beach after a storm:

In 1550 an extraordinary fish was caught near Oresund and sent to the king in Copenhagen. He had a human head and a monk’s tonsure on his head. He is dressed with scales and a kind of monastic hood. The king ordered the fish to be buried. Several drawings were made of the fish, which were sent to various crowned persons and naturalists of Europe.

King Christian III of Denmark depicted this weird sea monster that had been trapped and sent to Emperor Charles V of Spain in the mid-16th century. Numerous pictures of the sea monk in numerous animal books presumably trace back to these sketches.

Described as a “fish” that externally resembled a human monk in his habit, the monster was 15 feet long. It was caught in the waters of Copenhagen when it became the victim of a herring net.

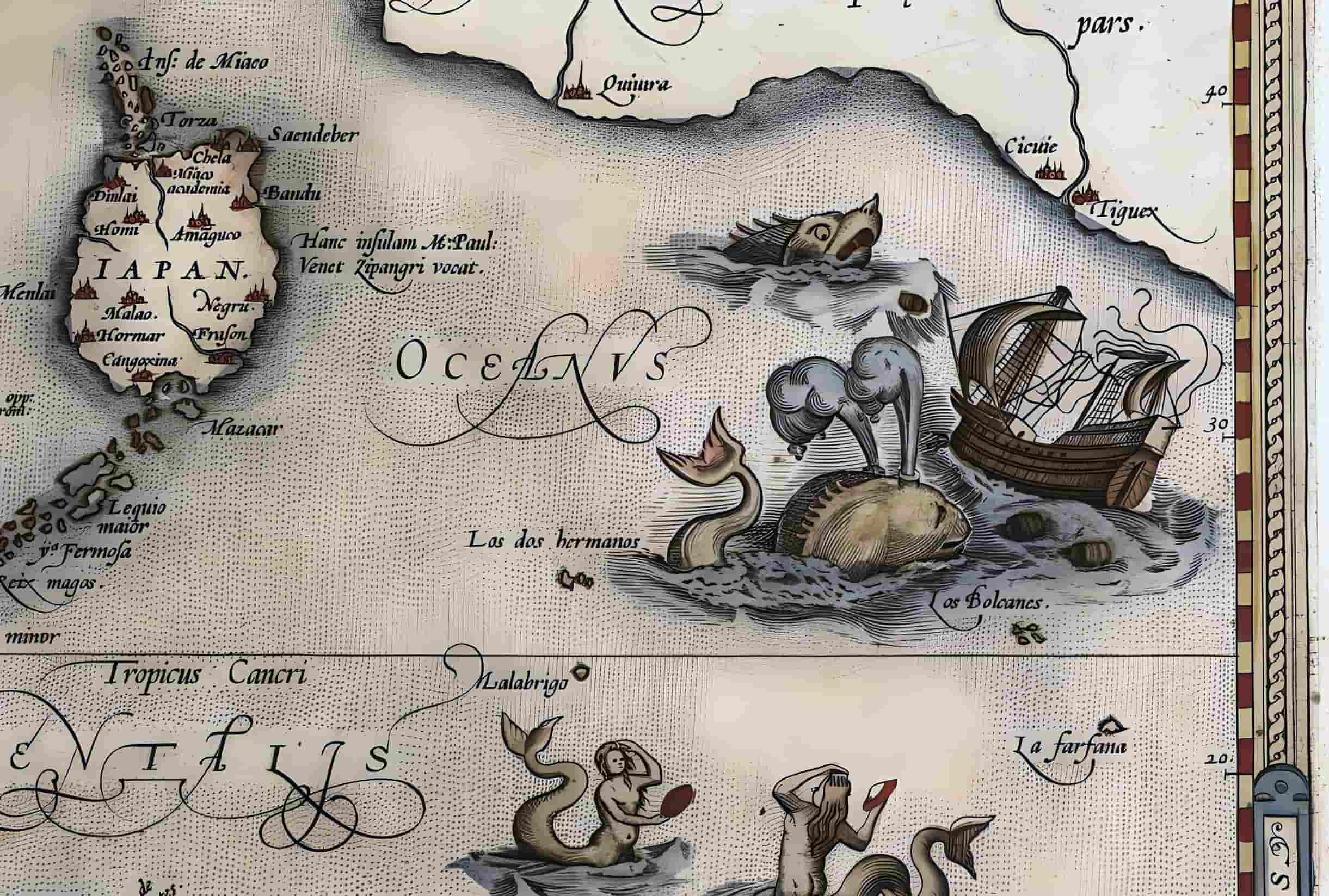

From the fish books of Pierre Belon and Guillaume Rondelet to Conrad Gessner’s Fish Book (1558), Japetus Steenstrup cites a total of eight references for the sea monks during this time period.

Gessner’s book included not only a description of the sea monk but also images of him and the bishop fish. Other fabled animals, including the phoenix and the unicorn, are mentioned in Gessner’s works, although his writings are often ambiguous (like a novel) on whether or not these creatures really exist. He enumerates the reports of the sea monk sightings while maintaining a crucial distance. According to him, the monster’s face was as dark as an Ethiopian’s.

The “bishop fish,” seen in 16th-century European literature for the first time, is a comparable figure to the sea monk.

It Looked Like a Catholic Monk

A character in the fish book is called the “sea monk,” and he has a humanoid face and wears scales for attire like Catholic monks. His skull is tonsured like the medieval depictions of Megenberg. In François Deserps’ costume book from 1562, the sea monk appears not long after Gessner’s fish book, with the sea bishop once again. When compared to Gessner’s work, the figure here seems bulkier, the face displays a grimacing, shark-like smile, and the clothing appears more humanlike.

Like Lucas Cranach’s portrayals of the “Donkey Pope” and the “Monk’s Calf” the rationale for these alterations like the sea monks might be anti-Catholic animus.

Several texts, such as Gaspar Schott’s Physica Curiosa (1697) and Robert Chambers’ Book of Days (1863/64), continued to mention the sea monk well after the 16th century, when it had mostly been forgotten. First proposed by Steenstrup in 1855, the octopus confusion theory attempted to provide a scientific explanation for sea monk sightings.

Merfolk like sirens, tritons, naiads, and nereids were occasionally linked to the sea monk in 16th-century writing.

Even species he had never seen alive, such as the armadillo, were faithfully represented by Gessner based on accessible knowledge. Animals having unusual characteristics, such as flat feet or a bell-shaped trunk on an elephant, were shown in Gessner’s works. The skill with which Gessner was able to depict guinea pigs led to his being famous as Zurich’s first guinea pig breeder.

Real Animals Similar to the Sea Monks

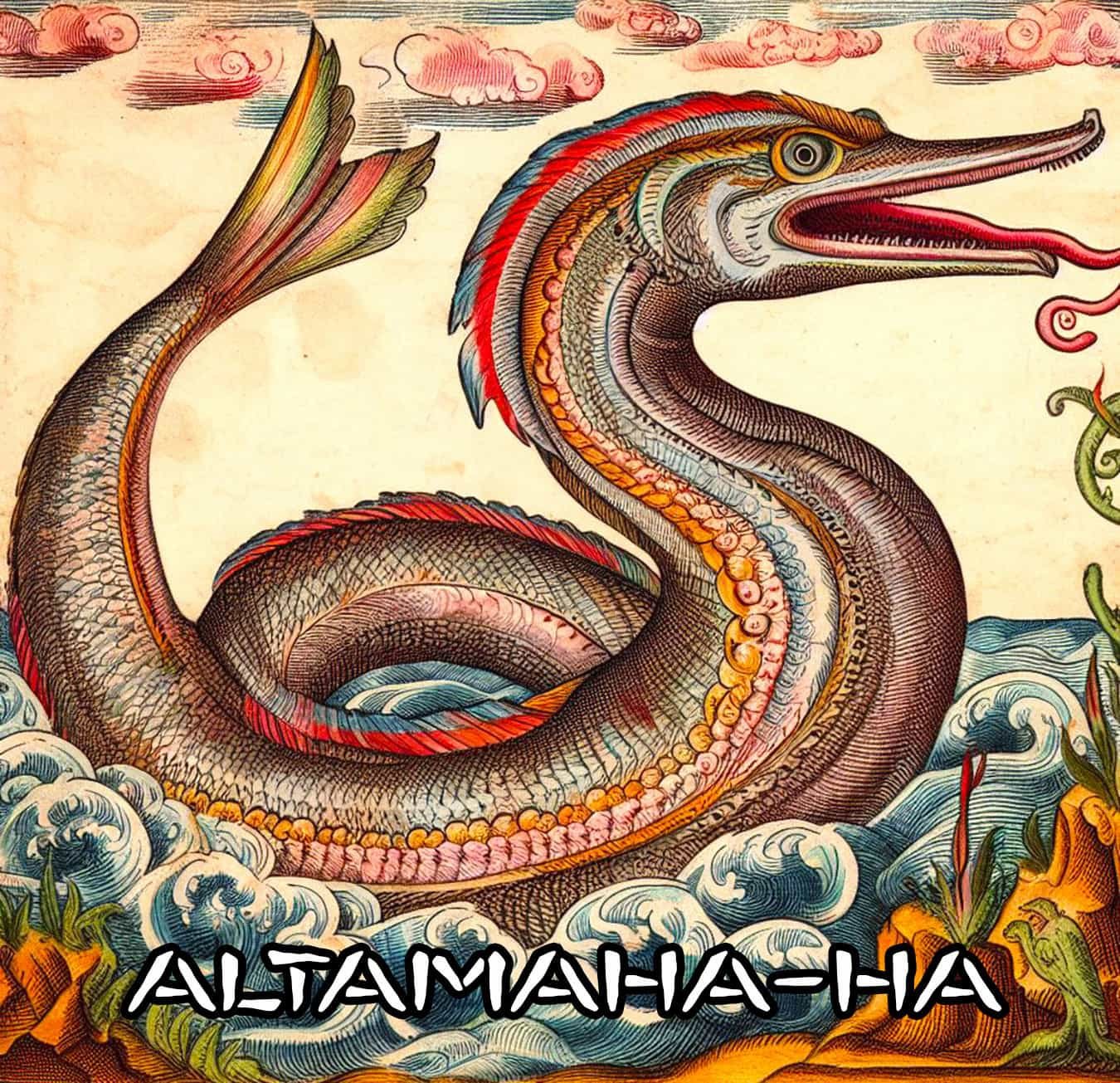

In 1855, Steenstrup equated the sea monk with an octopus. He speculated that an octopus would closely match the description given by the sea monk’s preserved body form and other features. He assumed the tonsure-like form on the top of the skull was an ink sac.

Anglerfish, often known as monkfish, is a good example of a contender for this interpretation, while in more recent times other creatures have been brought into play as possibilities. The angelshark (monkfish), which resembles a monk to a lesser extent and would be a better fit for the reported size of the sea monk than the squid typical in the North Atlantic, is often mistaken for a monkfish.

Seals, which are widespread in the North Atlantic and also resemble monks, might be another option. Although dried and taxidermied rays (Jenny Haniver) may seem like dead sea monks, they provide no explanation for living individuals who are spotted. Regardless, the little oral history precludes any convincing explanation for the sea monk phenomenon.

The bishop fish and the Japanese umibōzu are only two examples of the many mythical marine animals that take their inspiration from or are based on religious people.

Explanation of the Sea Monk Myth

The sea monk was not all that uncommon and was sometimes pulled up with herring in fishing nets. Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) of Zurich, Switzerland, discovered the species he would later draw for his “Historia animalium (“History of the Animals”) in the basements of the royal palace in Copenhagen, where it had been held as a “curiosity” since its capture in 1550.

Professor Steenstrup drew a conclusion from matching these images to historical accounts of the “monster”: it was a ten-tentacled cuttlefish, often colored black and red, with suckers and warts on the skin and suckers on the tentacles, which might easily be mistaken for scales. The “sea monk” mythos, therefore, seems to have its roots in the all-too-common cognitive bias of unconsciously “doctoring” the unknown with the known.

Some people think the sea monk is either a gray whale, a walrus, or a large stingray (known as a “monkfish” in Germanic nations). In addition to that, Jenny Haniver was also a “humanoid monster,” but it was in reality a hoax of a dried and mutilated sea creature that was given the body of either a “devil” or “dragon.” This could be another explanation for the sea monk.

In Modern Culture

Several video games include a monster known as the Sea Monk, including Lost Kingdoms II and Final Fantasy XI.