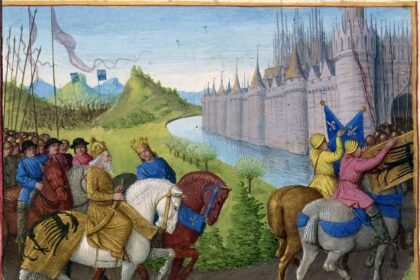

Second Crusade (1147-1149)

The Second Crusade was primarily triggered by the fall of the County of Edessa to Zengi, the Atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo, in 1144. This was the first Crusader state to fall back into Muslim hands, causing alarm in Europe and prompting calls for a new crusade.