The siege in the medieval period was one of the most crucial components of warfare at that time. During the medieval era, sieges were much more common than field battles because they were cheaper and required a smaller army, resulting in lower losses. A besieger, after a successful siege, gained much more territory and gains than if they had fought a battle. The siege tools and machines of the early medieval period were often based on older, ancient designs, showcasing the effectiveness of ancient siege techniques. However, these machines soon began to improve, leading to the development of new siege tactics and siege engines.

Considering that every European ruler wanted to maintain control over their land, castles began to be constructed. Initially, castles copied defense techniques from ancient fortifications, but later, new methods of defense were introduced. Castles featured moats, drawbridges, circular towers, double walls, and more defensive structures. The pinnacle of the medieval period is referred to as the golden age of castles. However, this doesn’t mean that offensive methods were not being perfected. The trebuchet was the first original siege engine of the medieval period. It was invented towards the end of the 12th century and became widely used in the 13th and 14th centuries. Eventually, cannons began to be used, altering the nature of medieval warfare and marking the end of castles and, consequently, medieval siege techniques.

Sieges in the Early Medieval Period

In the early medieval period, all siege engines were replicas of ancient machines. Defensive structures were entirely similar to those in ancient times. It is more than likely that the quality of these machines and structures was inferior to their ancient predecessors due to a decline in manufacturing standards and a lack of skilled individuals. However, towards the end of this period, the machines began to improve and carry the traditional features of medieval warfare.

Frequent wars and, consequently, sieges were common in early medieval Europe. This was caused by frequent invasions and the instability of the states at that time. The Byzantine Empire retained traditional Roman siege techniques and also invented new, effective weapons. The most impressive weapon of that era was Greek fire. Greek fire was likely invented by the Syrian engineer Callinicus of Heliopolis. It was a flammable mixture that ignited and exploded after a certain time.

Greek fire was widely used in naval battles as well. The Byzantines considered Greek fire a gift from the gods, and the composition of this weapon was so jealously guarded that the formula and manufacturing process remain unknown. The main component was likely naphtha, with other ingredients possibly including ice, sulfur, resin, and petroleum. Greek fire proved itself many times, and its use is credited with prolonging the existence of the Byzantine Empire. Although the composition of this weapon was carefully guarded, eventually, Arabs and likely the French started using Greek fire.

When the Roman Empire fell in 476, its military and, therefore, its siege techniques were adopted by the barbarians. The quality of weapons was initially lower than in ancient times, but constant wars led to their improvement. Barbarians settled in former Roman cities and quickly learned Roman ways. Medieval warriors used the books of the ancient Romans as their main source of information. A significant contribution in this regard was Vegetius’ work, “De Re Militari” (“Concerning Military Matters”). In this book, Vegetius describes siege tactics and provides readers with various pieces of advice. Towards the end of their empire, the Romans started using purely medieval siege structures. Circular towers, often attributed to medieval siege techniques, were actually invented by the Romans, and medieval warriors rediscovered them only at the end of the early medieval period. Water-filled moats, drawbridges, and grates, which were later adopted by the barbarians, were also employed.

-> See also: The Technologies of the Roman Empire Ahead of Their Time

The Emergence of Castles and Their Utilization

The castle was a unique medieval structure, and the existence of castles is tightly associated with this period. Castles originated in the 10th century, and their significance declined during the 16th century. The main reason for the decline of castles was the discovery of gunpowder and the invention of cannons. The castle served as accommodation for the social elite, who were concerned about their safety.

The castle had multiple functions: it protected its inhabitants, guarded trade routes, and served as a strategic point for all armies. Castles were built on the smallest possible territory, which brought numerous advantages. The construction of a castle was cheaper, required fewer soldiers for defense, and provided attackers with fewer options for assaults. Determining the exact origin of the first castles is challenging. So far, the oldest discovered castle was built around the year 950 in France and was named Doulé-la-Fontaine. Although Doulé-la-Fontaine Castle was constructed from stone, during the same period, there were common fortifications with earthworks.

These fortifications had several advantages but also disadvantages. Since their defenses consisted of earth mounds, ditches, and palisades, this type of fortification was very cost-effective and could be erected during wartime. The downside of earthwork fortifications was the need for frequent repairs, as the mounds quickly deteriorated. This type of fortification was called motte-and-bailey, where “motte” refers to a mound and “bailey” to outer fortifications or the castle courtyard.

The shortened term is motte. Similar to stone castles, determining the origin or development of motte fortifications is challenging. Historians and archaeologists have come to the conclusion that the first motte fortifications originated in France or Flanders, with the estimated time of origin being the 10th century. The primary reason for constructing a motte was frequent enemy raids, necessitating a quickly fortified point provided by the motte. The largest concentration of this type of fortification was found in Normandy and Brittany.

Over time, stone castles emerged from the motte fortifications. The Normans, who settled in the region of Normandy, were pioneers in siege techniques and were the first to extensively construct stone castles. In the eleventh century, there was a mass construction of stone castles, and the use of motte fortifications declined. The increase in the number of castles was driven by the stabilization of Europe and European states, which sought to defend their territories with stone castles. Some progress was also noted in defensive techniques.

Circular towers were erected in newly built castles (though square towers were increasingly visible), offering greater resistance to enemy attacks. Elements of Byzantine and Arab defensive techniques were introduced and brought back by crusaders returning from their expeditions. A medieval castle was constructed primarily from stone, but a synthesis of stone and earthworks was not uncommon. Castles of that time lacked a moat, drawbridge, portcullis, and fortified gates, which became integral parts of high medieval castles.

High Medieval Castles

High medieval castles represented a synthesis of the best practices from both ancient and medieval times. Old, ancient defensive strategies, such as circular towers and drawbridges, reappeared during this period. The re-emergence of ancient defensive practices was mainly influenced by a growing interest in Roman literature. However, it was not only the influence of ancient literature. Sieges were frequent during the medieval period, allowing castle builders to observe the effectiveness of castles and learn from their mistakes.

The development of high medieval castles was significantly influenced by Byzantine and Arab fortifications. The Byzantines and Arabs, engaged in constant warfare, mutually influenced and copied each other’s defensive strategies. The Byzantines, in particular, were masters of siegecraft, as they were often the ones under attack from neighboring aggressors. During the Crusades, European warriors encountered magnificent oriental fortresses. The massive walls of the city of Constantinople made the greatest impression on the Crusaders and inspired some medieval castles.

During the Crusades, the Crusaders learned to build highly impressive castles, with one of the best examples being the Krak des Chevaliers. These castles exhibited a phenomenon that emerged in Europe over the next few years. Not only were they the first concentric castles (see below), but there was also an increased emphasis on external walls.

In early medieval castles, the greatest emphasis was placed on the outermost wall (of course, if the castle had more than one wall) and especially on the main defensive tower. The main defensive tower was typically the site of the toughest battles. In high medieval castles, the main defensive tower represented the last place of refuge (the castle defenders usually surrendered before the battle for this tower began). Most high medieval castles had double walls and, together with several other elements, formed concentric castles. The outer walls were lower than the inner walls, a design choice made to facilitate the defense of the castle. This ensured support for besieged units shooting from the higher walls. Castles of this type were constructed throughout Europe, with the greatest number found in France and England.

Many cities and small states were able to maintain their independence thanks to their powerful castles. Castle construction was a relatively expensive undertaking, but it paid off. Castles were much cheaper than future modern fortifications.

Castles varied, but a typical high medieval castle can be described: it had a moat that not only prevented attackers from approaching the walls directly but, more importantly, protected the castle against hostile mining. Towers were mostly circular in shape, as these towers were more resistant to attacks and mining. Gates were heavily fortified, featuring a drawbridge and one or two portcullises. The castle was, of course, of the concentric type and was built on an elevation. A castle described in this way posed a formidable challenge to any army.

Siege Weapons of the Early and High Middle Ages

Siege weapons of the early and high Middle Ages were, without exception, replicas of ancient machines, and their construction was only slightly modified. Typical medieval weapons such as trebuchets or cannons began to be used only in the late Middle Ages. Given that castle construction was continually improving, it is not entirely clear why siege weapons did not also see improvement. One reason may be that these weapons remained effective.

However, archaeological finds suggest that attackers were often defeated. Another reason may be that medieval builders or engineers simply did not have access to enough suitable technologies or trained engineers. This indirectly confirms the invention of powerful siege weapons in the late Middle Ages, coinciding with a greater proliferation of knowledge and advancements in metallurgy. Although the high medieval castle was increasingly sophisticated, there was still a chance of its conquest. Medieval warriors had a choice of many more or less effective siege weapons.

One of the simplest and most primitive weapons was the ordinary ladder. The medieval ladder was almost always made of wood and equipped with hooks or teeth that could be lodged in the walls. The ladder was a widely used weapon and could be seen in almost every siege. A mechanism that could lift ladders onto the wall was also observed. Every medieval castle was unique, so the height of its walls differed from others. This meant that not every ladder could be used to conquer a specific castle. Medieval soldiers addressed this by making ladders on-site to ensure that the ladder would reach the walls (though this often failed). Another simple siege weapon was the battering ram.

There were sophisticated battering rams covered with a wooden roof, mounted on wheels, suspended on a frame by ropes and chains, and equipped with a metal head. The common ancient practice of placing the battering ram on a crane was “forgotten” in the Middle Ages. Of course, very simple battering rams were also seen, representing nothing more than a wooden log. Undermining the walls was highly effective. Attackers dug beneath the walls and either destroyed the foundations or created a tunnel through which the attacker could directly access the castle. High medieval walls countered this by building moats and circular towers. If the tunnel was dug too close to the ground, the water from the moat could destroy the tunnel. Defenders often led counter-mining efforts to surprise attackers and collapse their tunnels.

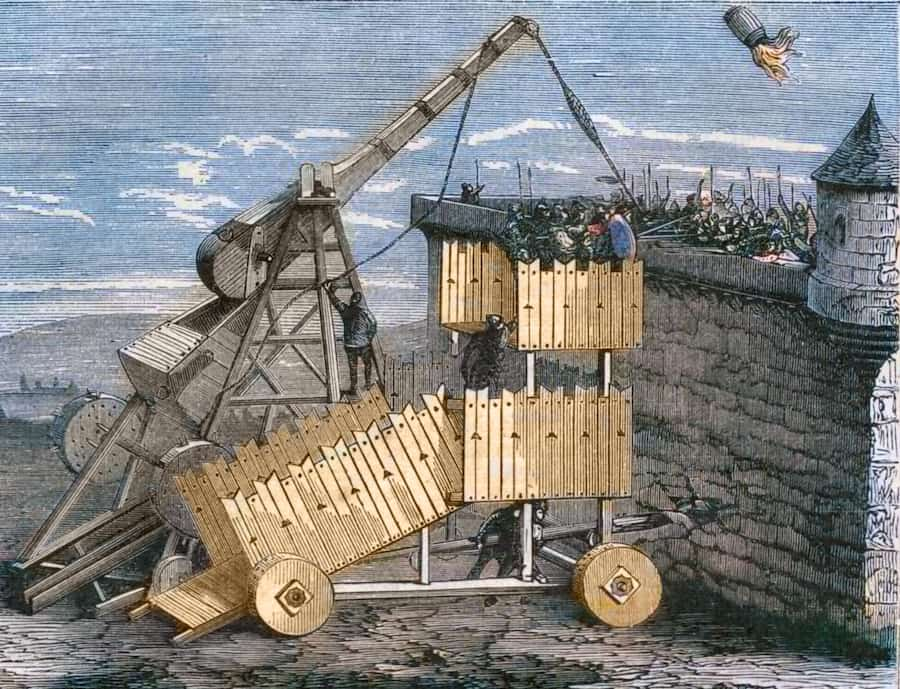

One of the most impressive siege weapons was the siege tower (also known as a belfry). Although medieval siege towers were quite effective, they could not be compared to their ancient counterparts. The construction of medieval towers was often imperfect, and their overturning or destruction was not uncommon. Many men lost their lives when their siege tower collapsed on its own.

Towers, like ladders, were often built on-site during a siege. They were as tall or even taller than the enemy walls, and a bridge was placed on top of the tower, allowing attackers to reach the walls. Siege towers could be equipped with catapults and battering rams to increase their offensive power. Siege towers were, of course, equipped with wheels. Protection was often provided using metal plates, rawhide (against fire), or willow twigs. They were transported to the walls either by soldiers or by animal teams, but the use of a crane also became practical. If the tower was well-built and had sufficient protection, it posed a very dangerous threat to any castle.

The last type of siege weapon was a projectile thrower. They worked on two principles: either using the bow principle (firing arrows) or utilizing twisted ropes. Machines firing arrows were used to clear enemy battlements of archers and other soldiers, while machines throwing stone projectiles were used to damage or destroy walls. Arrows were often equipped with a metal head, and projectile-throwing machines could launch metal bolts and barrels of Greek fire. Like all siege weapons of the time, projectile throwers were replicas of Roman machines, as evidenced by the names of these machines (ballista).

Undoubtedly, the most widely used projectile thrower was the mangonel. The mangonel was the successor to the ancient onager. It was used to launch stone projectiles, and its production was inexpensive and relatively fast. It was often equipped with wheels (like other machines), and its effective range was around 360 feet. An effective medieval tactic was also deception. Attackers would assault the castle in the evening, using ladders to get inside. If lucky, they could manage to open the gates. Betrayals were common, where a citizen or soldier of the castle intentionally opened the gates for the attackers.

Siege of the Late Middle Ages

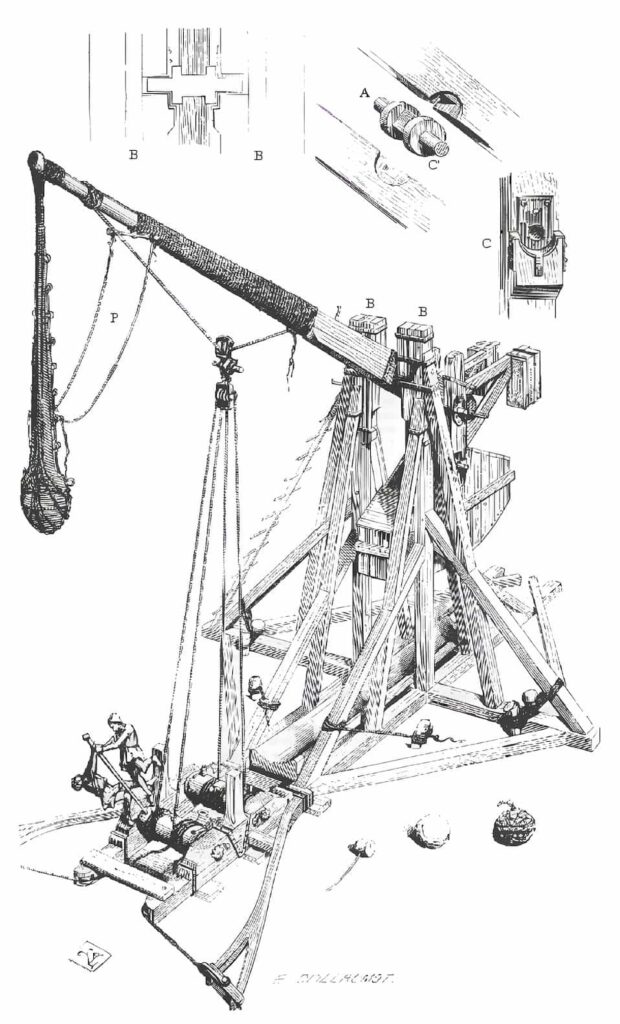

The sieges of the late Middle Ages were influenced by two major inventions. The first was the trebuchet, and the second was the invention of the cannon. The trebuchet was the first original siege weapon in the medieval world. It is challenging to pinpoint its exact invention. Some historians argue that it was invented in ancient times, but no trebuchet findings were made in the early Middle Ages, contradicting this claim. The first written mention comes from the first half of the 12th century. It is not entirely certain whether this written testimony refers specifically to the trebuchet or some other siege weapon. The trebuchet certainly began to be used around the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, but there is speculation that it might have been used as early as the beginning of the 13th century.

The trebuchet launched stone projectiles but differed significantly from weapons like the mangonel. The trebuchet did not use a twisted rope system at all but operated on the principle of a counterweight. Experiments conducted by Napoleon III show that a trebuchet could hurl a stone weighing 24 pounds at a distance of 597 feet. Modern experiments demonstrate that to throw a stone weighing one ton, 24 tons was needed as a counterweight. In these experiments, it was found that the trebuchet was an exceptionally accurate weapon.

The trebuchet was also the first weapon that truly threatened the existence of castles. According to contemporary accounts, a trebuchet could, after several shots, destroy less sturdy walls. Defenders of castles also attempted to use trebuchets, but their use within the castle was not very practical and was soon abandoned. Although the trebuchet was a very powerful weapon, capturing a well-fortified castle was still no easy task. Nevertheless, it was an invaluable weapon that made life easier for many medieval warriors.

Another and even more powerful weapon that ultimately put an end to the dominance of castles on the battlefield was the cannon. The Chinese were the first to manufacture cannons, but they couldn’t appreciate their qualities and lacked skilled metallurgists, so they made cannons out of paper or bamboo. It was only in Europe that cannons began to be made of iron. However, iron furnaces were not yet known at that time, so the cannons of that era could not be cast. Cannons were made by welding iron rods around a cylindrical core, and then iron hoops were threaded onto this welded tube. The first cannons were quite imperfect and were more suited for intimidating soldiers and horses than for destroying castle walls. It wasn’t until later that cannons were fully appreciated, and all European countries began mass-producing them.

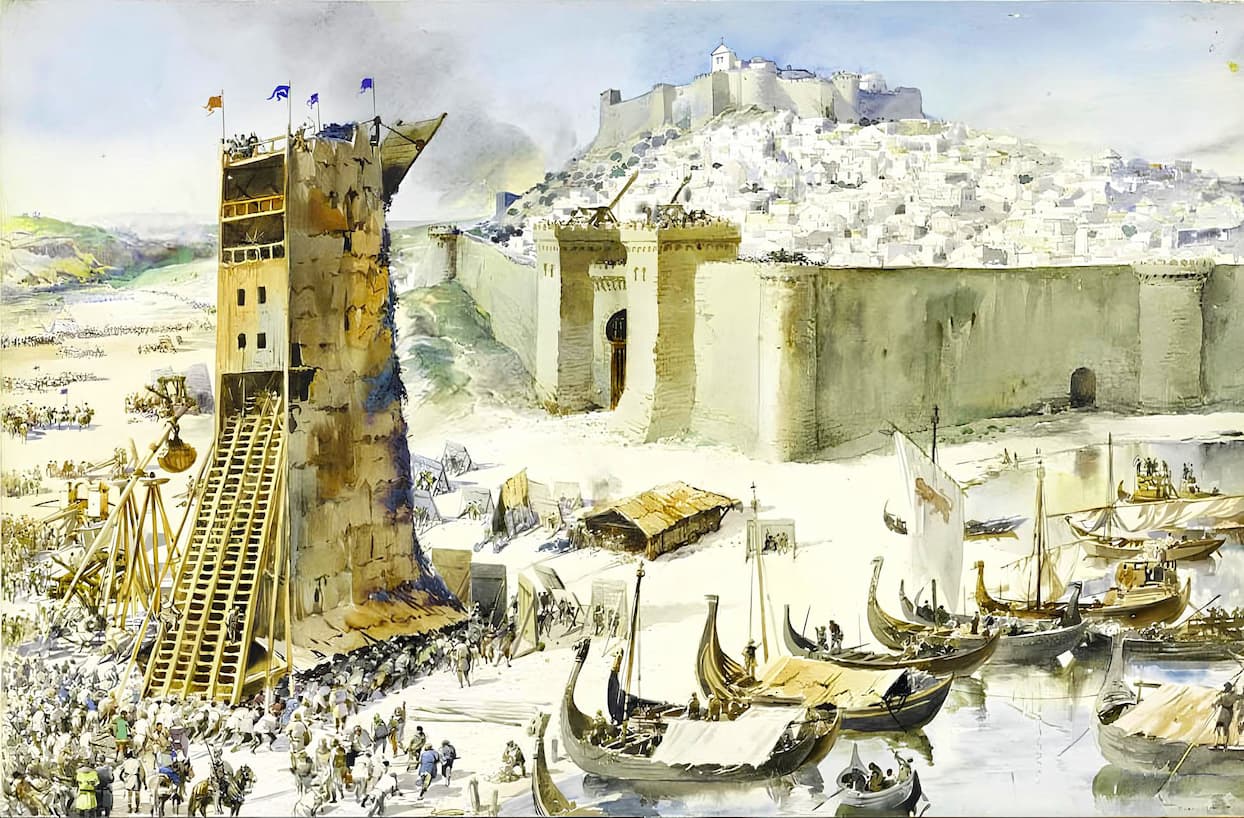

The first to use cannons in a major siege were not Europeans but the Ottoman Empire. It happened in 1453, during the siege of Constantinople. Mehmed II, the Conqueror, hired a Hungarian defector named Urban, who was to build giant cannons to help conquer Constantinople. These cannons were so large that they had to be cast right in front of Constantinople because their transport would be very complicated. From cannons at that time, not much was expected; they were to be placed in one location (further manipulation with such heavy cannons was very difficult) and fired until the enemy walls collapsed. Constantinople eventually fell, largely due to the cannons.

Castles across Europe succumbed one after another due to their unpreparedness against cannons. Castle walls were high but not very strong, designed so that attackers could not easily overcome them. However, these “thin” walls were vulnerable to cannons, which quickly destroyed them. This does not mean the end of fortifications. In the early modern age, sieges remained an important component of warfare, and even today, fortifications (bunkers) are built for the purpose of protection.

New fortresses began to employ new defensive tactics, and cannons started to be used within fortresses. These fortresses were very expensive, and only the wealthiest rulers, nobles, and cities could afford them. This resulted in the conquest of many small, independent states. The era of castles came to an end. With the invention of cannons, castles practically ceased to be built. Instead, the social elite began constructing more luxurious residences—castles. Although fortifications were still constructed, they never again dominated a region in the way castles did in Europe.