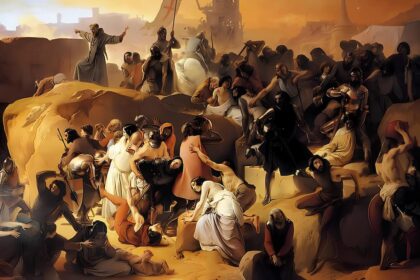

At the end of the 13th century, the Crusader States were in their death throes; the West had lost interest, and the last expeditions to save them had failed. Meanwhile, the Muslims had resisted the Mongol fury thanks to the Mamluks. It was these Mamluks who would finish off the Frankish states and mark what is considered the end of the Crusades, symbolized by the fall of Acre in 1291.

Divisions in the Latin Camp

The problems seen during Frederick II’s crusade, or even earlier (since the fall of Jerusalem in 1187), continued to worsen in what remained of the Latin States after Louis IX‘s departure in 1254. In this near-civil war, the Italian cities and military orders played a central role: the rivalry between Genoa and Venice and between the Hospitallers and Templars likely contributed to the weakening of the last Frankish states. This period is referred to as the War of Saint Sabas (a monastery in Acre), where the Genoese, allied with Philip of Montfort and the Hospitallers, clashed with the Venetians, supported by the Templars.

The war was mainly naval between 1256 and 1258, with one side attacking Acre and the other Tyre. Peace only came in 1270 through Louis IX’s political intervention.

However, this did not resolve the dynastic conflicts in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which continued after Conrad III’s death in 1268. The Angevin house took control of the crown until the death of Charles (Louis IX’s brother) in 1285, after which the King of Cyprus reclaimed it. By then, it was too late; the Mamluks had long since launched their jihad against the Crusader States.

Fall of Acre

The primary architect of the Latin States’ downfall was Baybars, who had played a key role during Louis IX’s first crusade, defeating Robert of Artois at the Battle of Mansurah. Baybars was also instrumental in the 1260 Battle of Ain Jalut against the Mongols, and, feeling unrewarded, he killed the sultan and took his place! He first directed his jihad against the Mongols from 1260 to 1263, then turned to the weakened Latin States.

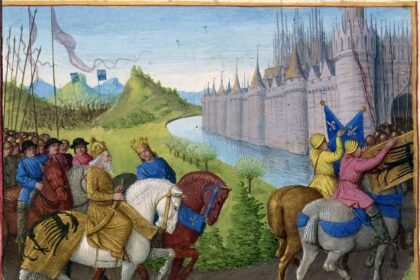

In just two years, he captured Caesarea and Arsuf, then Safed in 1266, and most notably Antioch in 1268, and the Krak des Chevaliers in 1271. Most of the major Crusader strongholds fell to the Mamluks within a decade. In 1272, Edward of England’s crusade (which was initially meant to join Louis IX in Tunis) slowed Baybars’ advances a bit, and Pope Gregory X tried to revive support for the Holy Land States, but to no avail.

Fortunately for the Crusaders, Baybars’ death in 1277, the succession disputes that followed, and a new Mongol invasion in 1280 provided them with a short reprieve. Their neutrality in the Mongol-Mamluk war allowed them to secure a ten-year truce with the latter. The Sicilian Vespers in 1282 weakened Angevin power, and Italian cities resumed fighting in Acre and Tripoli by 1285.

Taking advantage of this, Sultan Qalawun captured Tripoli in 1289 and aimed to finish off the Franks by turning his sights on Acre. His death gave the Latins a brief respite, but his son al-Ashraf Khalil laid siege to Acre in 1291. The city fell five weeks later, followed by the last remaining Frankish strongholds; it was the end of the Latin States in the Holy Land.

The End of the Crusades?

With the fall of Acre, the Crusader barons retained only Cyprus in the region, which would hold out until… 1571! Generally, 1291 is considered the end of the Crusades, at least the “official” ones—the eight well-known campaigns from historical accounts. Indeed, the concept of the Crusade as it had been conceived throughout the 12th and 13th centuries was no longer relevant, and for a long time, the Western kingdoms (except for Saint Louis) had lost interest in the fate of the Crusader States. On-site, it was the Italian cities and the Angevin house that acted, but with a more political and economic focus than ideological or religious: the reconquest of the Holy Sepulchre was far from their priority.

However, the idea of the Crusade, though it evolved, resurfaced in the following centuries.

It took new forms, targeted other geographical areas (the Teutonic Knights come to mind), and even led to new conquests, like that of Rhodes in 1310! The idea of the Crusade was rethought within a broader framework, with reforms (such as the merging of military orders, responsible for much division) or new alliances (for example, with the Mongols).

Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, several military expeditions, particularly against the Turks, were considered Crusades (often led by leagues).

Even the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 would be described as a Crusade…

It must be made clear from the outset that it is impossible to provide an exhaustive assessment of the Crusades or the Latin presence in the Holy Land. The religious, political, economic, and even cultural stakes are so varied, and the historiographical interpretations are so often contradictory, that attempting such a review is too risky. For that, the selected bibliography below is recommended. However, it is worth focusing on whether the Crusades were the first colonial ventures and their importance in the economic boom and maritime dominance of the Italian cities.