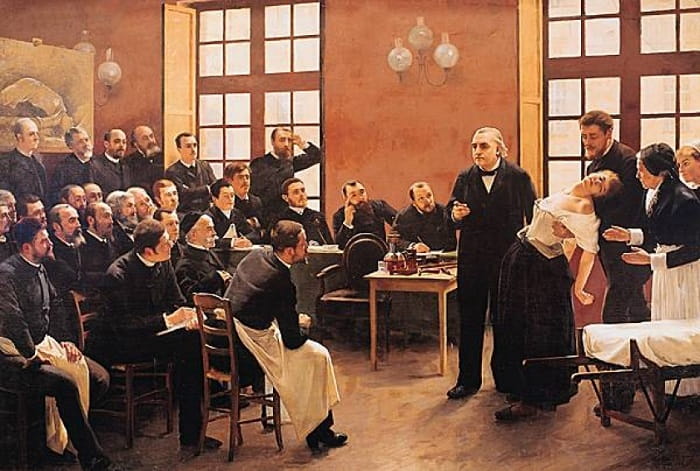

Sigmund Freud was born in Freiberg, in Pribor, now in the Czech Republic, in a relatively poor Jewish family. When he was 14, his family immigrated to Vienna. Freud then went to a medical school that was in its golden age at the time. In the school, he specialized in neurology under the supervision of Ernst von Brücke, a leading member of Helmholtz’s experimental medical school of the 1870s. In 1885, he went to Paris to study under the supervision of the first neurology professor and pioneer in clinical observation, Jean-Martin Charcot.

Although his visit to Charcot was quite brief, it was a turning point for Freud. Because it made Freud realize that some neurological disorders (like hysteria) are best understood through psychology. When he returned to Vienna in 1886, he began to practice clinical applications and specialized in such disorders. He remained in Vienna until he was captured by the Nazis in 1938. He fled to London that year (a year before he died in 1936, he was elected an honorary member of the Royal Society).

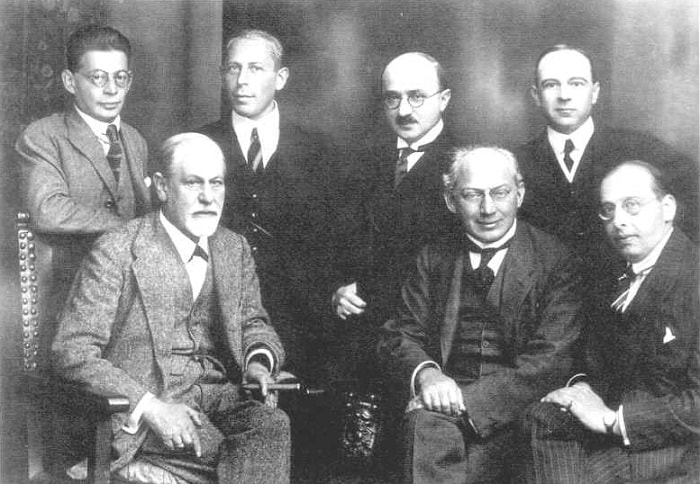

Who is Sigmund Freud?

What distinguished Freud from other scientists was the topic he studied. All scientists research a part of nature; such as the stars, mountains, birds, bees, molecules, and atoms. It doesn’t matter how small or large they are. After all, they are objects of investigation. Scientists seek to define them not only in the subjective way they appear to us, but objectively (as they really are). Subjectivity is considered the main source of error in science. Freud, on the other hand, made the observing object the study object—the thing that other scientists have sought to absolutely exclude from their work. It was inevitable that this would get him in trouble.

It is difficult to deny that subjectivity is part of nature. Subjectivity exists. As Rene Descartes suggested in his famous decree, subjectivity is the most precise part of nature for humans: “I think, therefore I am.” But things like thought (and emotion) do not exist in the objective world and are available only to us. This prompted Descartes to propose another famous decree, stating that nature appears to be made up of two distinct substances: mental substances and physical substances. This provision made it easier for scientists to exclude the mental part of nature from their work, but did not lead to the dismantling of the physical part. Mental elements (e.g. thoughts and emotions) still exist. It exists, but it is outside of science. This would put science in trouble.

How do mental causes have physical effects? A thought like “I will move my finger,” how does it really move the finger? This is the “body-mind” problem that annoyed the philosophers. According to scientists, Descartes’s conclusion must be wrong; as objects with mass and energy cannot be affected by things without mass and energy. The first law of thermodynamics (the conservation of energy), the basis of our understanding of physics, is in contradiction with this possibility. This led to the general conclusion that Descartes’ philosophy should not be taken into account.

Sigmund Freud’s approach to psychology

There were two mainstream alternatives to Sigmund Freud’s approach. Freud himself adopted the first alternative theory prior to performing psychoanalysis. This latter theory later came to the fore as an oppositional alternative to psychoanalysis. The first theory was not the mind itself, but rather the attempt to examine the physical “activity scene”—the brain—to infer the laws of the mind from the functions of the brain.

Sigmund Freud did this until 1895. Although not the majority of scientists, many argued that studying the physical connection of subjectivity is more scientific (objective) than examining subjectivity itself, and that subjectivity does not exist at all. Subjectivity involved only the manifestations that could eventually be reduced to physical things.

The problem with this cunning theory was that it turned us back to where we started and once again threw subjectivity out of science. Because no one can explain how subjective manifestations can be reduced to physical things, or in other words, how physical things lead to manifestations. Therefore, Freud abandoned this theory, in his own words, “in 1895 or 1900 or somewhere in between” before The Interpretation of Dreams was published in 1899.

Another mainstream alternative was the “behaviorism” theory. This theory began to be recognized in the 1920s and did not directly study the mind. Instead, it studied the mind’s observable inputs and outputs—its reactions to the stimulus. From these observable events, the laws that formed the responses were created. These were the laws of the mind. Although no methodological assumptions were required, most behaviorists went a step further and claimed that the mind (subjectivity) does not exist. They reduced the laws of the mind to what they called “learning.” It is not difficult to guess why they did this: there was no such thing as an object in the inherent nature of the mind. The mind was not an object. Today’s mainstream approach—cognitive neuroscience (which comes from both neuroscience and behaviorism)—still largely ignores this phenomenon.

Solving the mind-body separation

So what was Freud’s theory then? He took the phenomenon of subjectivity (calling it the phenomenon without parallel) as the starting point. He then closely observed thousands of examples of objective experience in the standard-setting. On this basis, he tried to enact laws that support experiences. Sigmund Freud was very aware that he did not do regular science by doing this, and said: “It still strikes me as strange that the case-histories I write should read like short stories and that, as one might say, they lack the serious stamp of science. I must console myself with the reflection that the nature of the subject is evidently responsible for this, rather than any preference of my own.“

That is why Freud is largely remembered by his case histories. The first of these was “Anna O” (the case history of his colleague, Josef Breuer), who observed that her symptoms improved instantly when she talked about the psychological traumas that trigger them. This case is the origin of “speech therapy.” Freud continued to report similar observations in many cases of hysteria (such as “Dora”) and other neuroses (“Mouse Man”, “Little Hans”, and “Wolf Man”).

The main discovery was that the events that triggered neurotic symptoms could only be understood by tracing it back to the first link (the infamous Oedipal complex), which was expressed in the form of strong sexual and aggressive feelings towards people. ultimately reduced to the instinctive nature of our species. Freud concluded that the basic mechanism of neurosis was the unsuccessful suppression of instincts. He then compared this theory with the mechanism of other mental illnesses caused by the unsuccessful attempt to deny disappointing things in the outside world, not by instincts (Judge Schreber case).

Sigmund Freud and metapsychology

Sigmund Freud called the laws he obtained through inference as “metapsychology“. With this theory, he tried to solve the mind-body problem (he aimed “to transform metaphysics into metapsychology”). Laws governing subjective spiritual life were supposed to be similar to those governing physical life, according to Freud. This was claimed by his teachers from the Helmholtz school; these teachers used to pledge the following official oath: “No other forces than the common physical-chemical ones are active within the organism; in those cases, which cannot at the time be explained by these forces, one has either to find the specific way or form of their action by means of the physical-mathematical method, or to assume new forces equal in dignity to the chemical-physical forces inherent in matter, reducible to the force of attraction or repulsion.“

The psychological forces (libidinal impulse, suppression, denial, etc.) assumed by Freud provided him with a language in which he could describe the functional organization of the mind, which he knew was in parallel with the functional organization of the brain. Freud initially attempted to extract the laws of the mind from the function of the brain, then tried to extract the laws of the brain from the functioning of the mind. He did this methodical reversal because there were no scientific tools available at the time to study how the brain worked.

The laws Freud made from his observations were functional (abstract) laws, not physiological (concrete), like those of modern cognitive psychology. It is often unknown that Freud pioneered this “functionalism” theory. He did this to reconcile the fact that “although the mind and brain have different observational starting point it is, after all, the same ‘thing’ and therefore should have a common arrangement at the bottom.” (He called this abstract thing the “psychic apparatus.”) Therefore, Freud insisted on this strange statement: “The physical process is unconscious in itself.“

The concept of the unconscious psychic apparatus gave Freud the long-awaited link between the mind and body. Today, Freud’s scientific heirs are reviewing and correcting his results with the tools of modern neuroscience (for example, with functional brain imaging), while at the same time trying to correct the mistakes of neuroscientists who still ignore the inherent properties of the mind and thus miss the basic phenomena of how it works.

Sigmund Freud quotes

“One day, in retrospect, the years of struggle will strike you as the most beautiful.”

“Being entirely honest with oneself is a good exercise.”

“Most people do not really want freedom, because freedom involves responsibility, and most people are frightened of responsibility.”

“Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth later in uglier ways.”

“We are never so defenseless against suffering as when we love.”

“Out of your vulnerabilities will come your strength.”

“Where does a thought go when it’s forgotten?”

“A woman should soften but not weaken a man.”

Sigmund Freud

Bibliography:

- Cohen, David. The Escape of Sigmund Freud. JR Books, 2009.

- Cohen, Patricia. “Freud Is Widely Taught at Universities, Except in the Psychology Department”, The New York Times, 25 November 2007.

- Eissler, K.R. Freud and the Seduction Theory: A Brief Love Affair. Int. Univ. Press, 2005.

- Eysenck, Hans. J. Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire. Pelican Books, 1986.

- Ford, Donald H. & Urban, Hugh B. Systems of Psychotherapy: A Comparative Study. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1965.

- Freud, Sigmund (1896c). The Aetiology of Hysteria. Standard Edition 3.

- Freud, Sigmund and Bonaparte, Marie (ed.). The Origins of Psychoanalysis. Letters to Wilhelm Fliess: Drafts and Notes 1887–1902. Kessinger Publishing, 2009.

- Fuller, Andrew R. Psychology and Religion: Eight Points of View, Littlefield Adams, 1994.