Sinterklaas (Dutch: Sint-Nicolaas) or simply De Sint, in French Saint-Nicolas, is the main character and the name of the holiday for children celebrated in the Netherlands on the eve of St. Nicholas’ birthday, which falls on December 5th. In Belgium and some former Dutch colonies, the celebration occurs on December 6th, the actual day of St. Nicholas’ feast. On the island of Curaçao, Sinterklaas arrives by ship at Sint Annabaai Bay a week after his arrival in the Netherlands.

Traditionally, Sinterklaas arrives in the Netherlands by steamship, always on the first Saturday after the feast day of St. Martin, who passed away on November 8th. Dutch children believe that Sinterklaas comes specifically from Spain to visit them. In 2007, he visited Kampen in the Overijssel province as the first location, and in 2006, he was ceremoniously welcomed in Middelburg in the Zeeland province. In 2009, Sinterklaas planned to arrive in Schiedam on November 14th.

The arrival of Sinterklaas means that from that moment on, children can place their shoes by the fireplace every evening before bedtime (Dutch: De schoen zetten) to find small gifts (mostly sweets) the next morning, provided they have been good. On the evening of December 5th, Sinterklaas brings a package with a significant gift (Dutch: Pakjesavond) to children who have been obedient throughout the year.

The celebration of Sinterklaas is solemnly observed throughout the Netherlands, except in the town of Grouw (Grou) in the Friesland province, where the celebration of Sint Piter takes place on February 21st. For instance, the Polish equivalent of the Dutch holiday Sinterklaas is the celebration of Saint Nicholas’ Day on December 6th.

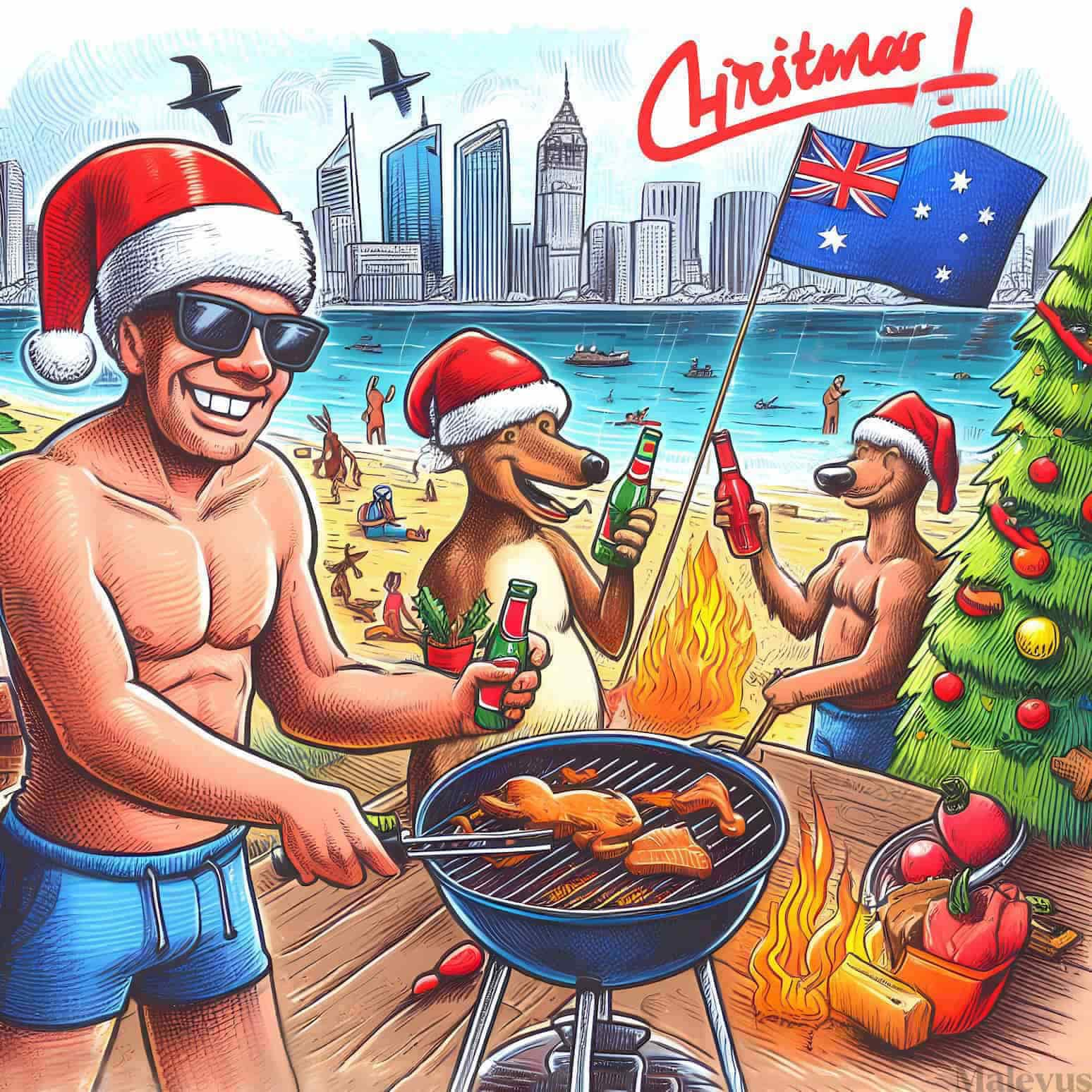

Saint Nicholas’ Day is also observed, although somewhat less commonly, in other countries: Luxembourg (known as Kleeschen), Austria, Switzerland (Samichlaus), France (Saint Nicolas), Germany, Romania, Slovenia (Sv. Miklavž), Serbia (Sveti Nikola), Turkey (Noel Baba), Brazil (Papai Noel), the Czech Republic (Mikuláš), and Hungary. In the United States and the United Kingdom, we encounter the figures of Santa Claus and Father Christmas, respectively, with a fairy-tale-commercial-advertising character, and the period of gift-giving extends from St. Nicholas’ feast to New Year’s.

Contemporary Celebration

According to public opinion surveys, the Dutch consider Sinterklaas the most popular holiday, leading to calls for December 5th to become an official public holiday. In 2009, 55% of the Dutch declared they would celebrate Sinterklaas solemnly, with an average spending of more than 120 euros on gifts. The holiday is most popular among individuals aged 18 to 34 (around 65%). Chocolate letters are definitely the most popular sweets.

Dutch children emotionally experience Sinterklaas’ arrival, manifested by stress-like symptoms. Psychologists caution against frightening children with the idea that if they misbehave, they may be taken to Spain in a sack by Sinterklaas or not receive a gift. Additionally, Sinterklaas songs can evoke anxiety in the youngest ones.

For commercial reasons, Sinterklaas arrives almost a month earlier (November 15th, 2008), and characteristic sweets and pastries for this period sometimes appear on store shelves as early as late September. This causes confusion in the minds of preschoolers due to their lack of a fully developed sense of time. Television starts airing Sinterklaas programs by the end of October. Parents of children with ADHD complain that kids get excited at the sight of toy advertising brochures dropped into mailboxes, leading to additional tension and misbehavior.

The issue of children’s stress related to the Sinterklaas holiday (Dutch: Sinterklaasstress or Sintstress) is commented on in the media. Until recently, Sinterklaas would quietly leave the Netherlands on December 6th and return to Spain by ship. A new trend has emerged: organizing a festive farewell to Sinterklaas (Dutch: Sinterklaas uittocht). Especially autistic children feel the need to say goodbye to Sinterklaas.

Origin of the Holiday

The tradition of celebrating Sinterklaas is connected with the figure of Saint Nicholas of Myra, who was a bishop in Myra, the capital of Lycia, in the early 4th century, and even incorporates older historical elements.

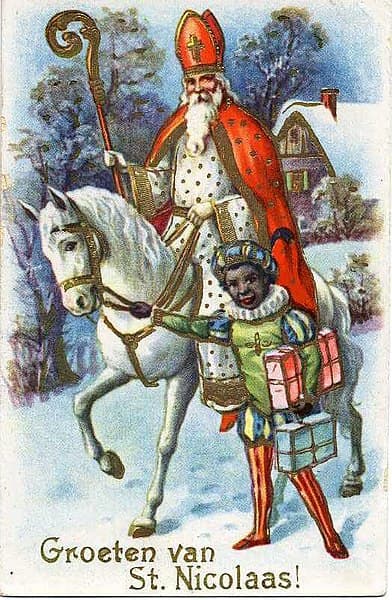

Historians have not been able to confirm whether Bishop Nicholas had a long, gray beard, like Sinterklaas. According to beliefs, Sinterklaas moves across the roofs of houses on a gray horse named Amerigo, while the Walloons believe it is a donkey. Sinterklaas is dressed in an episcopal robe and a hat called a mitre in Latin, holding an ornate bishop’s crook, or crozier, in his hands.

Initially, Saint Nicholas’ Day was celebrated only in Eastern Europe. It was only in the 13th century that it was decided to celebrate Saint Nicholas’ feast in Western Europe. Around the same time in Utrecht, the shoes of four poor children were filled with coins, and efforts were made in other cities to organize small gifts for the poor. In the early days of the Eighty Years’ War, Calvinist priests attempted to discontinue the solemn celebration of Saint Nicholas’ Day due to perceived heretical elements. However, the holiday was already so popular that the call for a boycott did not receive a positive response, even from the Protestant part of society.

Between the figures of Saint Nicholas of Myra and the Germanic pagan god Odin, many similarities can be found. Odin also rides a gray horse (Sleipnir) with eight legs, holds a spear in his hand, and moves through the heavens. During the festival associated with the astronomical phenomenon of the winter solstice, young girls would ask Odin for the gift of an image of their future fiancé. This is why images of young men are found on cookies (speculaas poppen). Odin was always accompanied by two ravens: Hugin and Munin, possibly explaining why the assistant of the Dutch Saint Nicholas wears a feather on his hat.

The belief that Sinterklaas arrives from Spain to the Netherlands is most likely historically conditioned. In the 16th century, trading ships brought expensive items, delicacies, spices, and oranges from Spain to the Netherlands, despite the ongoing war between the two states (1568–1648). Trade flourished, and the Dutch were convinced that everything from the south, including Sinterklaas, came from Spain. Perhaps the relocation of Saint Nicholas’ remains from Muslim-occupied Myra to a tomb in Bari, which was then under Spanish rule, in 1087 played a part.

Another concept suggests that the Dutch identified Sinterklaas as a Catholic saint with the Roman Catholic Spaniards who ruled over the territory of present-day Holland in the Middle Ages. The treats exchanged at that time, such as mandarins, sweet almonds, and figs, came from Spain, so people, when giving each other gifts, said that Sinterklaas brought these delicacies, especially from Spain. In the second half of the 19th century, the arrival of Sinterklaas from Spain to the Netherlands was described in a children’s picture book by teacher Jan Schenkman, depicting the holiday celebrations in large cities.

Placing Shoes During Sinterklaas

In the Netherlands, gifts for Saint Nicholas’ Day, known as Sinterklaas, are placed in children’s shoes that have been previously set out by the fireplace. In the period between Sinterklaas’s official arrival in the Netherlands and December 5th, for several days, children place their shoes by the fireplace before going to bed so that the next morning they can check what they received as presents. If they behaved well, small gifts such as chocolates, candies, marzipan figures, or cookies could be found in the shoes. Sometimes, children also put a carrot or a glass of milk for Amerigo, Sinterklaas’s horse, in the shoe.

This tradition dates back to the 15th century, when initially only the poor would place their shoes in the church on the evening of Sinterklaas, December 5th. The wealthy would add a little something to the shoes, and on December 6th, which is the official day of Saint Nicholas’ death, the income would be distributed among the poor and beggars. Archival materials confirming the existence of this custom date back to 1427 in the Saint Nicholas Church in Utrecht. Over time, Sinterklaas became a family celebration, and by roughly the 16th century, children started placing their shoes in the largest room of the family home for Sinterklaas to hide presents in them.

The 17th-century Dutch painter Jan Steen captured the morning of Sinterklaas in two paintings. In the painting titled Saint Nicholas’ Day, you can see what Saint Nicholas brought as gifts for the children. The most generous was a little girl who received a doll and a bucket full of toys and sweets from Saint Nicholas. A boy on the left wipes away tears as he finds a twig in his shoe. An older girl triumphantly holds his shoe up, while another boy laughs, pointing to the shoe with the twig. Only the grandmother standing in the back looks kindly at the crying boy and reaches behind the curtain, perhaps hiding a gift for him. In those times, boys often found twigs or a small bag of salt in their shoes.

Evening of Gift Packages

On the evening of December 5th, Sinterklaas leaves, usually by the fireplace, packages with grand presents for children as a reward for being good throughout the year. During the economic crisis and the outbreak of World War II, the tradition of giving gifts for Sinterklaas was not yet a common phenomenon in the Netherlands. It was only the prosperity that followed the end of World War II that contributed to the popularization and further development of the custom of exchanging gifts on December 5th. Right after the war, in many Dutch families, gifts were placed on the respective person’s chair, and the ritual was surrounded by an air of great mystery.

Over time, the image of Sinterklaas underwent a transformation: from an invisible, magical gift-giver to a great friend of children with the appearance of a benevolent grandfather. This figure, with a sack full of presents, visits children in their homes, accompanied and assisted by his black helpers.

Initially, parents gifted children with handmade trinkets, later mostly with store-bought items. Large corporations and trade unions also adopted the custom of giving packages to the children of their employees or members. In big cities, it became popular among students, friends, and colleagues to draw lots and exchange small gifts for Sinterklaas. This way, the tradition ceased to be solely the privilege of parents giving gifts to children. Even the possibility of electronic drawing of lots appeared on the Internet.

Sweets and Pastries Typical for the Sinterklaas Period

During Sinterklaas’ stay in the Netherlands, traditional sweets and pastries appear in bakeries and on food stalls in department stores and supermarkets, which are not available for the rest of the year. Examples of sweets and pastries associated with the Sinterklaas holiday:

- chocoladeletters – chocolate letters of various sizes: milk, dark, or white chocolate; often placed in children’s shoes; the most common choice is a large chocolate letter, typically the initial of the recipient’s name.

- marzipan figurines – small figures of fruits or animals made of marzipan.

- amandelstaaf/boterletter – a mass of ground almonds and sugar with lemon juice in puff pastry shaped like a long roll or the letters S, M, or W.

- borstplaat – candies, usually heart-shaped, with vanilla or cocoa flavor, consisting mainly of sugar and milk.

- taaitaai – hard and chewy, very difficult to bite cookies with a light anise flavor, often shaped like Sinterklaas figures.

- speculaasstaaf – a mass of ground almonds and sugar with lemon juice in speculaas dough, a slightly under-risen dough with a dense structure, characterized by its distinctive aromatic and spicy taste and scent derived from a blend of spices including cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, ginger, cardamom, and white pepper.

- deegmannetjes – buns made from semi-sweet dough in the shape of little figures with raisin eyes.

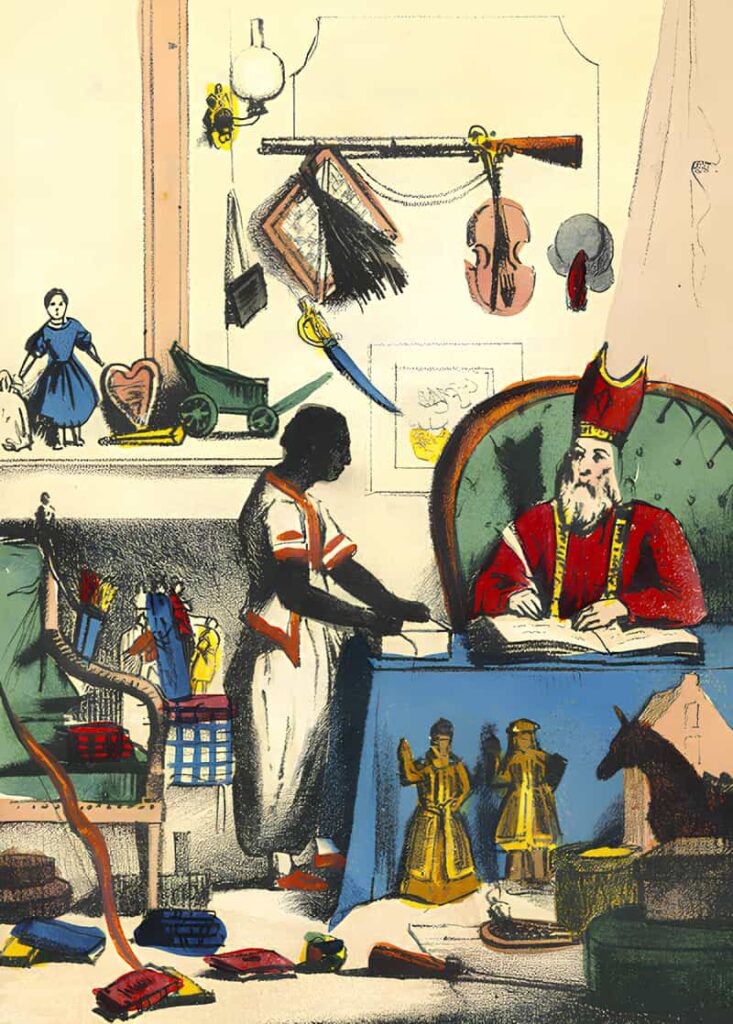

Zwarte Piet

Sinterklaas is accompanied and assisted by one or several Zwarte Pieten (Zwarte Piet, pronounced: pit). The task of Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) is to carry the bag of presents and climb through chimneys into homes to secretly place gifts into the shoes children have set out by the fireplace. The black assistant of Sinterklaas is dressed in the costume of a page from the late 16th and early 17th centuries, similar to the attire worn by courtiers in royal courts.

Before World War II, Sinterklaas was accompanied by only one black assistant. After the war, Canadian soldiers who took part in organizing the first post-war Sinterklaas celebration, unconstrained by the rigor of tradition, initiated the participation of several Zwarte Pieten. Since then, Sinterklaas has always been accompanied by several, and even dozens, of dark-skinned helpers, each fulfilling a different role.

While Sinterklaas is a calm and dignified elderly gentleman, his helpers behave playfully, engage in mischief, make jokes, perform acrobatic tricks, and also distribute unique, tiny, spiced cookies to children and passersby on the street, called “kruidnootjes” and “pepernoten.” Kruidnootjes are small, round, dark brown, dry cookies with a flat bottom. Pepernoten are cookies with anise in the form of light brown, irregularly shaped cubes.

The origin of the black servant of Sinterklaas is not precisely defined, and there are many theories, such as:

- a demon converted by Saint Nicholas,

- a boy from Mauretania, which would explain the color of his skin,

- a subdued devil,

- an Ethiopian boy named Piter (from Petrus), whom Sinterklaas bought at a slave market in Myra, granted freedom, and out of gratitude, he remained by his rescuer’s side,

- a former assistant of an Italian chimney sweep, as he has the skill of walking on roofs, is dressed in a chimney sweep suit, and carries a broom.

The black skin color of Sinterklaas’s helpers and the golden earrings that Zwarte Pieten wears are often criticized for allegedly promoting racism by invoking the tradition of slavery. In Flanders, children refer to Zwarte Piet as Pieterknecht, which means Pieter’s helper. Pieterknecht is a politically correct term that does not refer to skin color.

Songs About Sinterklaas

In the Netherlands, there are numerous songs about Sinterklaas sung by children during this holiday. Examples of songs include:

- “Someone is knocking at the door” / Daar wordt aan de deur geklopt

- “He arrives, he arrives, dear, kind Sint” / Hij komt, hij komt, die lieve goede Sint

- “Children, listen, who is knocking there” / Hoor wie klopt daar kinderen

- “Oh, come and see” / O, kom er eens kijken

- “Sinterklaas little cape” / Sinterklaas kapoentje

Sinterklaas’ Attire

Sinterklaas’s attire is inspired by the robes worn by bishops, complete with the attributes associated with bishops. For practical reasons, Sinterklaas’s robes are often more modest. Sinterklaas typically wears a long purple cassock fastened with numerous buttons, over which he puts on a long alb, and a red stole draped around his neck.

Over this attire, he wears an elaborately decorated cape fastened in the front with a chain and two hooks. The inner side of the cape is gold-yellow or white.

When Sinterklaas is seated on his horse, the cape falls onto the animal’s back. On his head, Sinterklaas wears a red hat, which closely resembles a mitre, the headgear of bishops. In his hand, he holds a pastoral staff. He wears black boots on his feet and long, white, or occasionally purple gloves on his hands. On his ring finger, he wears a large, episcopal, golden signet ring with a ruby.

Controversies, Criticism, and Competition

The mutual exchange of gifts on Sinterklaas has historically faced opposition from the Protestant Church; for example, around 1600, celebrating this holiday was prohibited in Delft. Martin Luther opposed this Catholic custom. Even in 1895, the mayor of the town of Sluis spoke against celebrating the Sinterklaas ceremony in public schools. Presently, within the Catholic Church, there are voices of protest—opponents of Sinterklaas and Santa Claus point to the departure from tradition and the complete commercialization of the holiday.

In the late 20th century, Saint Nicholas in Poland and Sinterklaas in the Netherlands faced competition from themselves in the form of the American Santa Claus, known in Dutch as kerstman. Santa Claus initially became popular in the United Kingdom, where he is called Father Christmas, and then expanded his reach to almost all of Europe as Santa.

The name Santa Claus comes from the Dutch word Sinterklaas, which was incorporated into American English and Americanized by Dutch immigrants who arrived in America in 1614 and, among other things, founded New York, initially named New Amsterdam. At lightning speed, the historical figure of Saint Nicholas of Myra transformed into the commercially attractive figure of Santa Claus.