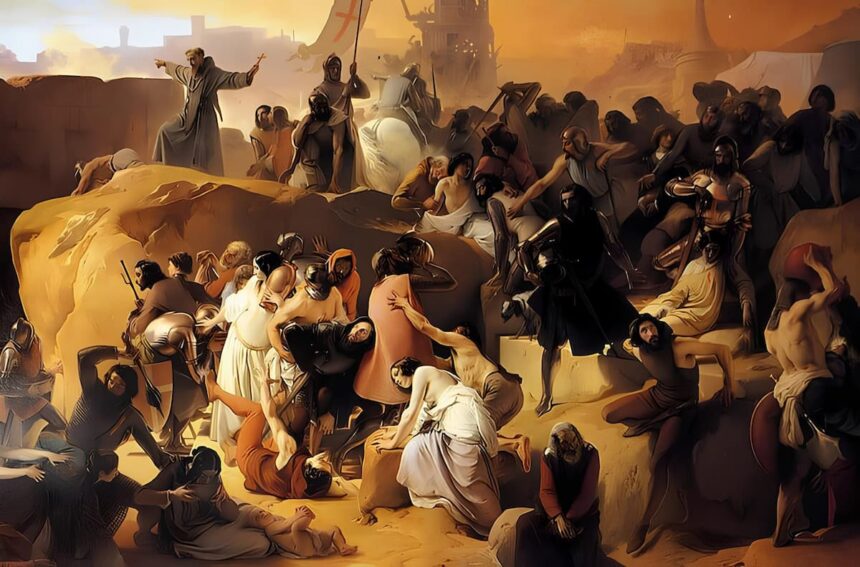

If Pope Innocent III was very active in calling for the Crusades, his record proves to be more than mixed, whether it was with the one diverted to Constantinople or the Fifth Crusade, which failed in Egypt, partly due to the pope’s legate. Innocent III himself died before the crusaders set out. It was time for Western rulers to take the lead, with one of the most significant among them, Frederick II Hohenstaufen. The German emperor was already a living legend, and it is impossible to summarize his character in a few lines. Therefore, we will focus on the political situation following the Fifth Crusade and Frederick II’s image at that moment, particularly regarding the papacy.

Context of the Sixth Crusade

Despite the rivalry between the Empire and the Church, it was Pope Innocent III who facilitated the election of the young Frederick. At the time, he was still young (born in 1194), living in Sicily when the pope decided to “abandon” the then Emperor Otto IV (excommunicated), making the Hohenstaufen the King of Germany. However, Frederick had to wait until Otto IV’s defeat at Battle of Bouvines (1214) for the imperial throne to effectively return to him.

He was elected emperor in 1215; then he took the cross, but, as we have seen, did not honor his promise, being too preoccupied with internal issues within the Empire and, it seems, not very motivated by the idea of a crusade. Even though he seemed to have been “made” by the pope, he did not wish to remain politically dependent on him.

However, Frederick quickly understood that leading such an expedition could allow him to present himself as the leader of the West, in opposition to the pope but also other rulers like Philip II of France

(Philip Augustus). He renewed his promise in 1220 when Honorius III crowned him in Rome, but it was not until 1223 that Frederick II’s crusade began to take shape.

The pope still played a central role: first, he pushed the emperor to renew his promise, then he arranged his remarriage (he was widowed) to the daughter of the King of Jerusalem. This was concluded in 1223, at the same time as the crusade oath was renewed, with the departure scheduled for June 1225.

Nevertheless, Frederick II intended to decide the course himself and preferred to resolve his problems in Sicily rather than prepare for the crusade; as a result, he risked excommunication! He agreed to renew his vow, and the crusade was postponed to 1227. Frederick II bought time, using it to seize control of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (without yet setting foot there), forcing his father-in-law John of Brienne to take refuge in Rome!

He delayed his departure once again, which was too much for the new pope, Gregory IX, who excommunicated him in 1227!

However, the pope’s reasons seemed more complex, as his attention was focused both on the Kingdom of Sicily and that of Jerusalem.

Frederick II Finally on Crusade?

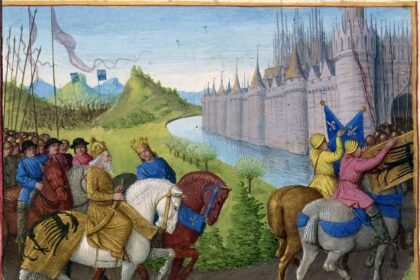

Despite his excommunication, the emperor finally decided to leave for the Holy Land at the end of 1228, accompanied by 500 knights. He first traveled to Cyprus, where John of Ibelin was serving as regent, and asserted his dominance by claiming that the island’s rulers were his vassals since it was his father, Henry VI, who had granted it to the Lusignans! The Ibelin family thus became fierce enemies of Frederick, but war was avoided thanks to the intervention of the Military Orders. He then proceeded to Acre, but there, the Templars and Hospitallers opposed him due to his excommunication!

However, he had the support of the Teutonic Knights. The emperor’s goal was twofold: to reclaim Jerusalem and to establish his authority as a ruler. The crusade was, therefore, not his only priority.

Treaty of Jaffa

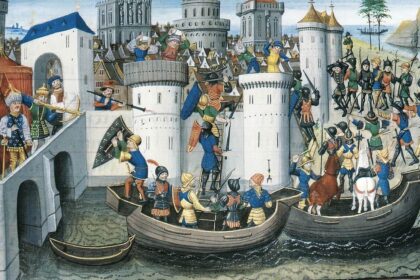

Frederick II decided to pressure the sultan by fortifying the strategic city of Jaffa. Success came quickly, as without a battle, he obtained the treaty bearing his name in the same city on February 18, 1229! He took advantage of a civil war among the Ayyubids.

This treaty restored the Holy City to the Latins (except for the Temple Mount), as well as several other places like Sidon, and regions that allowed for the partial reconstruction of the Kingdom of Jerusalem around it (and no longer around Acre), along with a ten-year truce. The unexpected success was significant, and Frederick II celebrated by traveling to Jerusalem himself in March 1229, where he was officially crowned and fulfilled his duty as a pilgrim.

However, the context was not in Frederick’s favor: he was still excommunicated, and his methods in Cyprus and Acre had earned him much hostility, particularly from the Templars (who had not regained their Temple, located on the esplanade still guarded by the Muslims). Moreover, his tolerance toward the Infidels (following his attitude in Sicily) was even less well-received, and he was criticized for his appreciation of Eastern customs, the Arabic language, and Muslim art, as well as dining with the sultan’s envoys and even the leader of the Assassins! He quickly left the Holy City, then the Holy Land, after a brief stay in Acre, where he was met with mockery and jeers…

Consequences of the Treaty of Jaffa

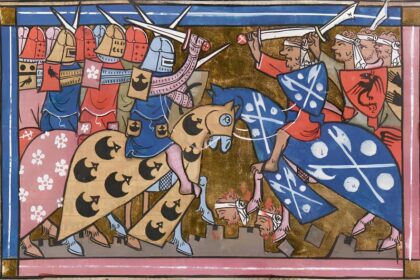

Frederick II’s crusade was much more successful than the previous ones (except for the First, of course), but the treaty and the circumstances under which it was signed diminished its significance. Firstly, the Latins of the East greatly resented the “imperial tyranny.” Secondly, the ten-year peace agreement prevented them from taking advantage of the internal conflicts still active among the Ayyubids. Finally, among the Muslims, this return of Jerusalem to the crusaders was deeply resented, and the Ayyubids were further weakened.

Jerusalem was eventually recaptured by force in 1244 by the Khwarezmians (fleeing from the Mongols), despite earlier attempts to strengthen the city’s protection. Indeed, in 1239, Pope Gregory IX had called for a new crusade, led by Thibaut IV, Count of Champagne, to protect Jerusalem. Despite some victories and the fortification of several strongholds, this effort ended in 1240 without consolidating the kingdom, although a new treaty was signed with Sultan Ayyub.

Frederick II left the Kingdom of Jerusalem in a deplorable state. His son Conrad was supposed to assume his role as sovereign, but Frederick first clashed with Patriarch Géraud upon his return to Acre. He was ready to storm his palace and confront the Templars but had to retreat to Sicily, where John of Brienne had launched a counterattack! Later, Frederick refused to send Conrad to the Holy Land, leaving the kingdom to struggle with internal conflicts. He also lost the support of Cyprus, which was retaken by the Ibelins in 1232. Fortunately, the pope decided to support the emperor, and the situation seemed to stabilize in the following years, despite the hostility of the Templars. However, this peace would not last long…