Social insects, such as bees and termites, refer to insects that form colonies and exhibit a hierarchical structure similar to human societies, with a queen and worker ants (or bees). These colonies are essentially family units, differing significantly from human societies in content. The opposite of social insects is solitary insects. Historically, the determination of whether an insect is social relied on the presence of hierarchical divisions within the group.

However, contemporary assessments emphasize the existence of infertile castes. From this perspective, insects exhibiting true social behavior are referred to as genuinely social. Research in this direction has led to the discovery of several insect groups demonstrating true social behavior beyond the mentioned classic groups. Presently, social insects are considered to possess true social characteristics. Nevertheless, due to the considerable differences in their nature, these newly recognized groups are often treated separately. This article focuses on social insects in the classical sense mentioned above.

Some insects, although not forming large colonies or exhibiting hierarchical divisions, are considered subsocial when parents and offspring cohabit. Additionally, the term “parasocial” is used when unrelated individuals form a group. These aspects are significant in considering the evolution of social insects.

Sociality

Most insects do not care for their hatched offspring. While some insects are known to engage in parental care, many abandon their offspring before they mature. In contrast, certain bees and ants not only care for their offspring but also continue to live together even after the offspring have grown, forming large colonies. Insects with such behavior are termed social insects.

In vertebrates, temporary family formations, where parents and offspring form families and engage in social relationships within a population, are common. The term “sociality” is used when a group, including multiple individuals or families, exhibits more complex structures and interactions than a mere gathering. Although challenging to precisely define, sociality generally refers to relationships resembling human societies.

Even compared to social structures in vertebrates, bees and ants forming large colonies appear remarkably similar to human societies. For instance, the presence of classes such as queens and worker bees, each with specific roles, resembles aspects of human societies.

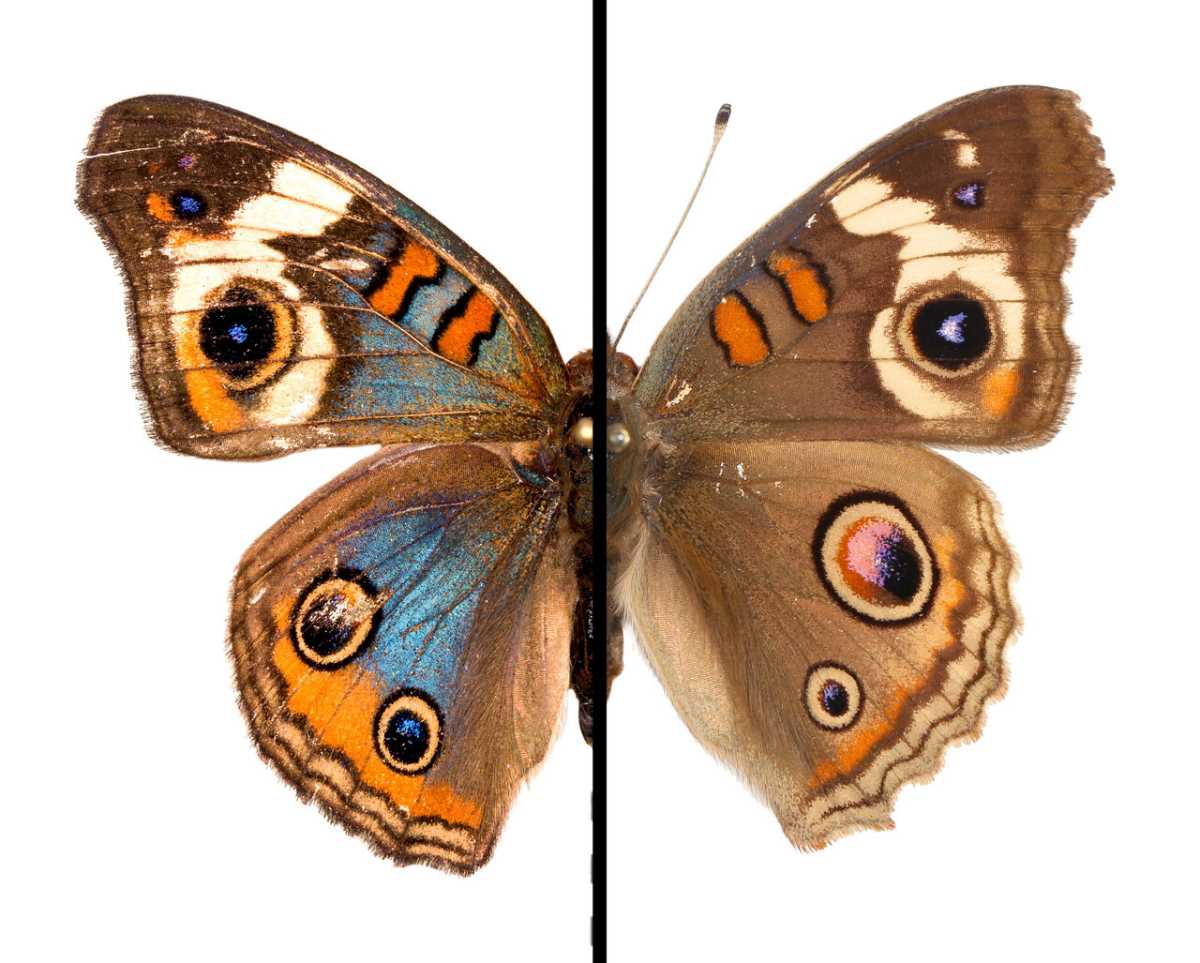

This has led to comparisons between insect and human societies. However, upon closer examination, differences emerge, such as morphological variations based on caste differences, reproduction limited to queen individuals, and the majority of colony members being siblings. These aspects distinguish insect societies significantly from vertebrate societies.

The social lifestyle of social insects has proven highly successful. Social insects constitute a significant portion of the animal biomass in terrestrial ecosystems. In the tropical rainforests of Brazil, for example, bees and termites make up 80% of the insect biomass, with bee biomass reaching nearly four times that of all non-fish vertebrates. Despite comprising only 2% of insect species globally, estimates suggest that social insects occupy 50% of the current biomass.

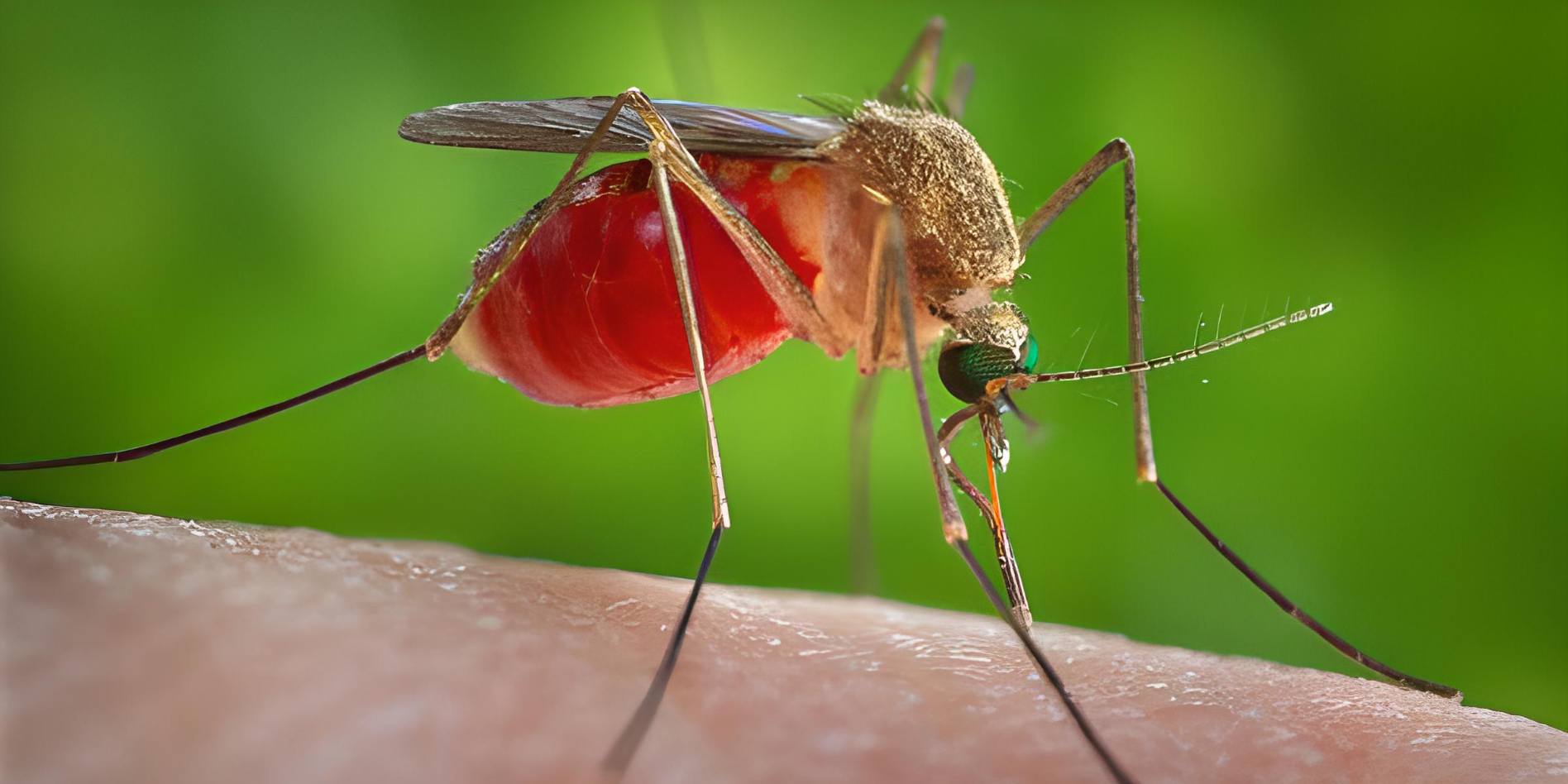

As a result, these insects play a crucial role in natural ecosystems. Bees serve as pollinators for flowering plants, wasps act as predators of insects, and termites play a vital role in decomposing plant matter, especially in tropical regions. Ants, with their diverse diets and lifestyles, contribute to various ecological aspects, including predation on small animals, seed dispersal, symbiosis with other organisms, and soil improvement.

Superorganism

In social insects, where members depend on each other for survival, and individual survival is challenging, as reproduction occurs within the group and involves the creation of a new colony, some consider the entire colony as equivalent to a single organism, terming it a superorganism. The concept was first proposed by the ant researcher William Morton Wheeler, who extensively studied social insects. He referred to these insect colonies as superorganisms. Although criticized by some, such as Kinji Nishinow, who disregards the existence of male bees, there is still recognition of the colony as a unit corresponding to an individual.

Various Social Insects

Sociality in Bees

Within the order Hymenoptera (including ants, where ants belong to the family Formicidae and taxonomically fall under Hymenoptera), there exists a variety of social behaviors, ranging from highly social to subsocial and solitary. Examples of traditionally considered social insects include ant species, potter wasps, hornets, and honeybees.

The societies of social bees and ants are run exclusively by females. From fertilized eggs, females (queens) and males are born. The queen, after mating with a male bee, constructs a nest alone. Male bees die after mating with the queen and do not contribute to nest-building. The queen continues to lay eggs while caring for hatched larvae.

Once the larvae mature into adult worker bees, they stay in the nest to assist the queen with tasks such as childcare, foraging, and nest construction, without participating in reproduction. In most bee species, queens and male bees are born in autumn, after which they leave the nest and mate, and while the queen overwinters, the rest of the colony perishes. Consequently, many bee colonies last only one year (although honeybees and certain ants can maintain nests for multiple years).

Ants, with very few exceptions, are fundamentally social insects. For instance, the trap-jaw ant exhibits subsocial behavior without a queen, but this is considered a secondary adaptation. Some ant species develop soldier ants with well-developed mandibles.

Sociality in Termites

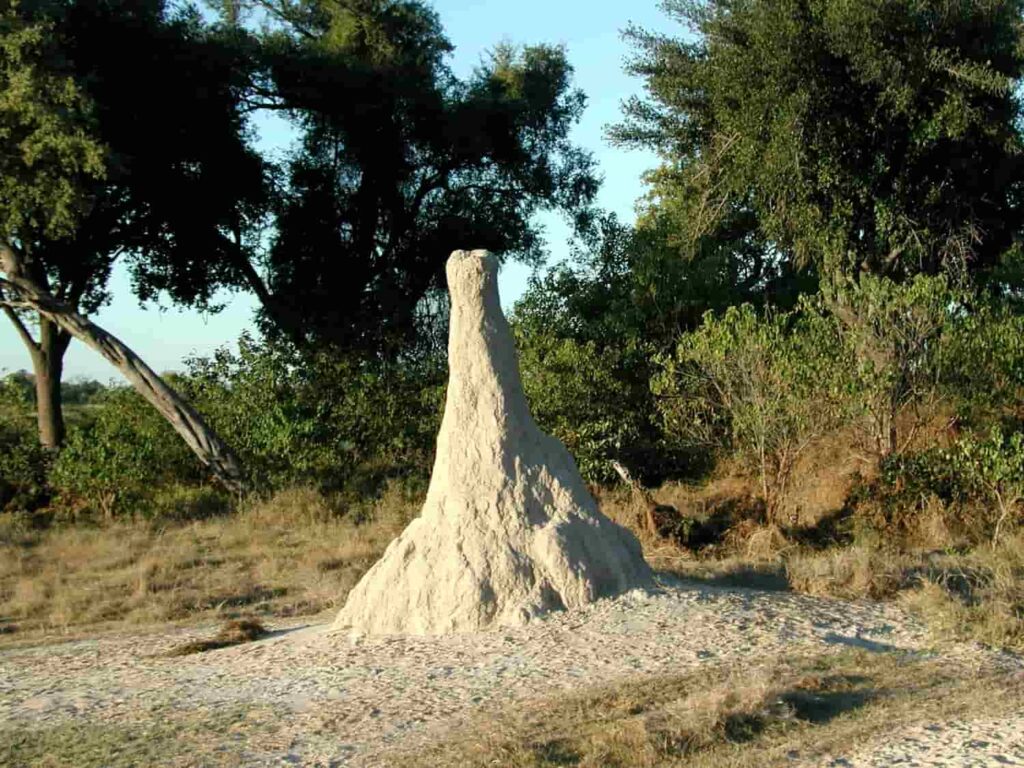

All termites exhibit social behavior. When winged termites leave the nest and mate, the resulting male-female pairs construct a nest. These individuals become the king and queen, engaging in repeated mating and egg-laying.

The offspring initially resemble their parents and, upon reaching a certain stage of development, transform into worker termites, assisting the king and queen with nest construction and other tasks. Some of their offspring develop into soldier termites as they grow. Soldier termites do not engage in reproduction.

The remaining worker termites, including some becoming winged termites, venture out of the nest. Many termite colonies endure through the year.

Colony Management

In many social insects, reproductive individuals (bee queens, termite kings, and queens) solely handle reproduction, while all other tasks are performed by workers (worker bees or worker ants). However, in species like hornets, where only reproductive individuals can survive the winter, reproductive members initially handle all tasks, from nest-building to foraging.

After worker emergence, they stay in the nest and focus exclusively on reproduction. In termites, some colonies build nests within wooden materials, while others, particularly in tropical regions, forage outside for food. In such cases, numerous individuals use pheromones as markers to navigate between the nest and food sources. In honeybees, the well-known figure-eight dance is performed to communicate the location of food sources to other colony members. Worker roles include carrying food and maintaining and managing the nest, as well as caring for larvae and reproductive individuals.

In species where a single individual (or pair) serves as the reproductive entity within a nest, there are instances where candidate reproductive individuals emerge from larvae within the nest if the reproductive members die. These are known as replacement reproductives.

When one of these becomes a new reproductive, the others are killed. Reproductive individuals release pheromones that suppress the appearance of other reproductive individuals. Many of these insects engage in behaviors like trophallaxis, the sharing of food mouth-to-mouth and facilitating pheromone transmission. Notably, species like the polygynous Myrmecina nipponica create large colonies with multiple reproductive individuals (multiple queens) and multiple nests, numbering in the tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands.

Evolution of Sociality

Charles Darwin himself faced difficulties explaining the treatment of social insects. Worker bees do not reproduce, and since traits are not passed on to offspring without reproduction, this posed a challenge.

One proposed explanation was the “queen manipulation” theory. It suggested that the queen, through pheromones, transforms offspring into worker bees. This trait, making one’s own offspring into worker bees, was selected through the queen, making childcare easier and allowing for the production of many offspring. However, this theory couldn’t dismiss the possibility of rebellion among worker bees. If a spontaneous mutation occurred in worker bees, rejecting the queen’s dominance, they could autonomously cease producing their own offspring.

This dilemma was resolved by Hamilton’s kin selection theory. This theory begins with the idea that in natural selection, it is not the individual but the traits expressed by the individual that are selected. An individual survives because it possesses certain traits, and the genes underlying those traits are selected. Therefore, the perspective shifts to the standpoint of individual genes, considering kinship.

Explaining this using the example of humans: when a parent has a child, from the parent’s perspective, the child carries half of the parent’s genes. Considering sibling relationships, the probability of one gene existing in the other is also 1/2. Thus, the gene responsible for caring for one’s daughter and the gene responsible for caring for one’s sister have similar chances of success.

In insects like ants and honeybees (Hymenoptera), where fertilized eggs become females and unfertilized eggs become males, the probability of one gene existing in the other between sisters born from the same parents is 3/4. In this case, the gene responsible for caring for one’s sister becomes more likely to be passed on to future generations than the gene responsible for caring for one’s daughter.

With this perspective, it becomes apparent that in Hymenoptera or any animal with a typical sex determination system, in groups with close kinship, supporting parents and increasing siblings without having one’s own offspring aligns with the goal of preserving one’s genes. If there are genes that induce behavior to assist parents in childcare instead of producing one’s own offspring, and if this behavior allows for a greater chance of preserving genes than producing one’s own offspring, and if it succeeds, those genes will survive through natural selection.

In this way, the existence of worker bees in social insects can be explained through the theory of natural selection. This led to the idea that the characteristic of social insects involves the presence of an infertile hierarchy. Kin selection theory has become a foundation for the development of sociobiology.

The New Meaning of Social Insects

In this way, the existence of an infertile hierarchy was shown to be a significant characteristic of social insects. This is unique even when compared to the social structures found in mammals. Consequently, this type of sociality is referred to as “eusociality.” Among previously known social insects, only some bees (and ants) and termites exhibit eusociality. E.O. Wilson defined eusociality as having:

- The presence of an infertile caste.

- Multiple generations living together.

- Cooperative care of young individuals.

With the foundation for eusociality now apparent, it became conceivable that there might be other eusocial insects. Due to the operation of kin selection, creating groups and maintaining high relatedness within those groups is crucial. Consequently, new instances of insects with infertile castes were discovered. In aphids, for example, soldier aphids were observed.

Aphids, after settling on plants through winged females and reproducing asexually, establish large colonies. Some aphids born in these colonies have sharp mouthparts and scythe-like front legs. They cling to attackers and defend the colony. However, these individuals do not survive to maturity. Since these aphids are clones born through asexual reproduction from the same mother, the relatedness is higher than in termites or bees, making the development of true eusociality more likely.

Subsequently, true eusociality was discovered in other insects, as well as in non-insect species such as shrimp-like creatures and mammals like naked mole rats. These organisms do not disperse, and high relatedness among individuals is maintained through inbreeding.

True eusociality is not exclusive to insects but is collectively referred to as “eusocial animals” or “eusocial organisms.” However, in biology, when “sociality” is mentioned without distinction, it may refer specifically to eusociality. In this context, humans are not considered eusocial animals. Currently, the naked mole rat is the only mammal known to exhibit true eusociality.

Ants, Bees, and Termite Nests

Some of these insects build massive nests, creating new environments and harboring diverse ecosystems. While they cultivate fungi and domesticate small animals such as aphids and scale insects in special cases, various small animals, similar to rodents or cockroaches in the case of humans, or freeloaders, food guests, or brazen burglars, inhabit their nests. In plants, the accumulation of food and excrement around the nest can increase soil nitrogen levels, and ants eliminate insects around the nest, resulting in selective sightings in the vicinity of the nest. These phenomena are described by terms like “myrmecophily” or “termitophily.”

Development of Sociality

Among bees, there are various stages of life, from solitary living to family living, and even true eusociality. Comparing these habits provides insights into how sociality evolved. There are two lineages of social bees. Some have species of subsociality where parents and offspring coexist, and it is suggested that true sociality evolved from such species. This was proposed by Wheeler, and the research by Kojiro Iwata also supported this theory.

- Examples include predatory species like longhorned bees and hornets. The ancestors of these were apparently predatory wasps like bee wolves and mud daubers. Predatory wasps anesthetize insects or other prey to feed their larvae. While many close their nests after laying eggs, some add additional prey midway. From such practices, family life involving childcare evolved, leading to the development of advanced sociality as seen in honeybees.

- Species like honeybees, which feed on flower pollen and nectar, have various solitary relatives among the bee family, such as carpenter bees and small carpenter bees. Many solitary bees store pollen and nectar in their nests and close the nest after laying eggs. From such solitary habits, they evolved through small-scale family group living, similar to mason bees, to the large-scale advanced sociality seen in honeybees.

On the other hand, the evolution from communal nesting to cooperative nesting and from such side-societal species to true eusociality is also discussed. This was proposed by C.D. Michener, suggesting that reproductive females gather to form nests, and then, through some means, all but one female loses reproductive ability, leading to true eusociality. In reality, in social bees and ants in temperate regions, groups mostly begin with a solitary female.

However, in tropical social bees, nest formation with multiple females is more common. In some cases of longhorned bees, within a group founded by multiple females, there is a clear linear hierarchy among females, and only the top female lays eggs. This hierarchical system was anticipated to contribute to the advancement of comparative sociology by allowing comparisons with the flocking behavior observed in birds and others. However, the subsequent progress seems to suggest otherwise.

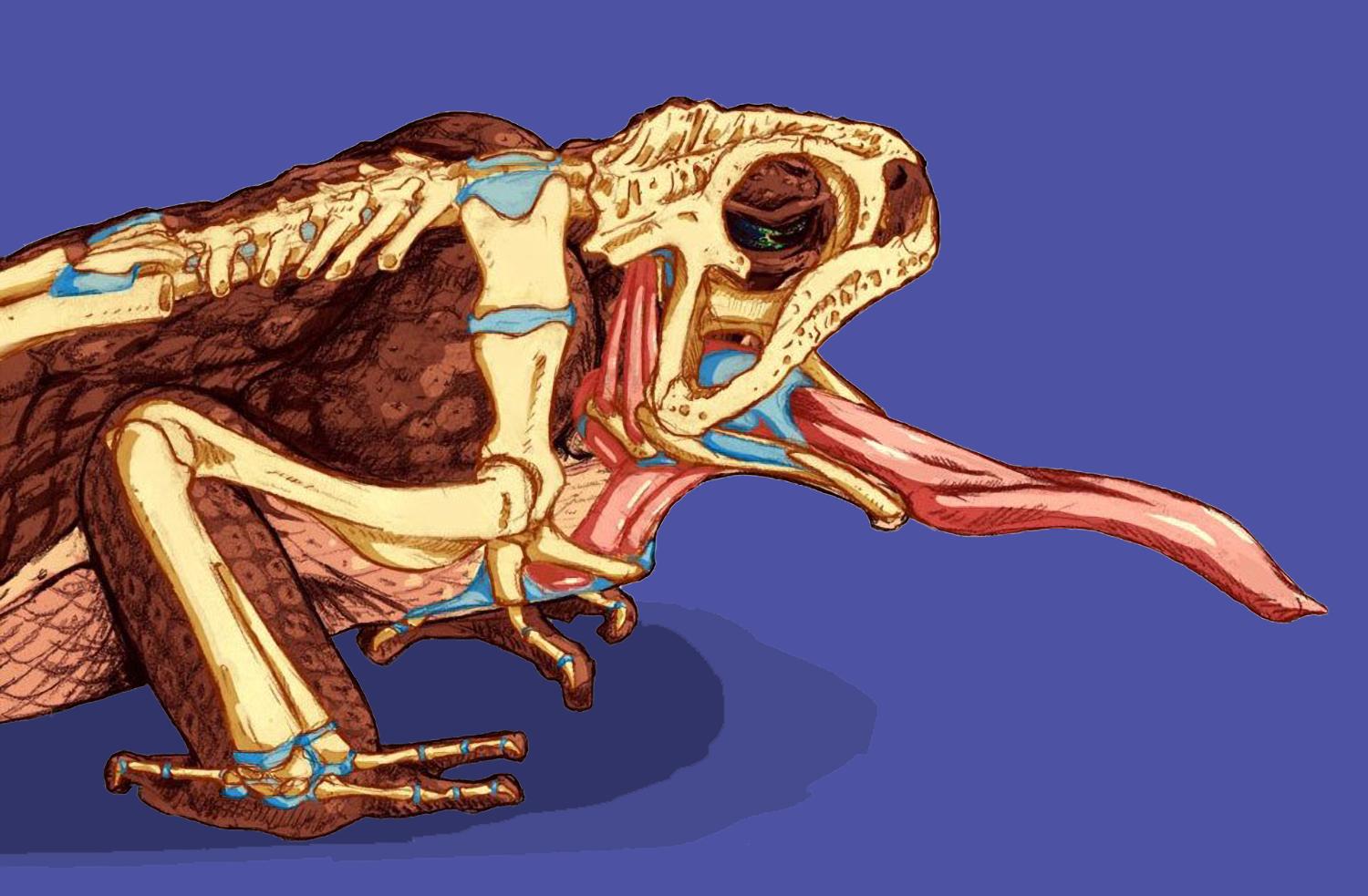

Termites are all eusocial. Unlike bees, termites do not perform direct feeding for their offspring, as termite larvae feed themselves. Therefore, there is a completely different history compared to bees. It is unclear how termites developed this way, but they possess symbiotic microorganisms capable of cellulose decomposition, enabling them to feed on wood. Born offspring need to obtain these microorganisms through mouth-to-mouth feeding from their parents, possibly leading to the development of family life. Furthermore, the abundance of inbreeding due to enclosed living in materials like wood may have increased relatedness, although this is debated.