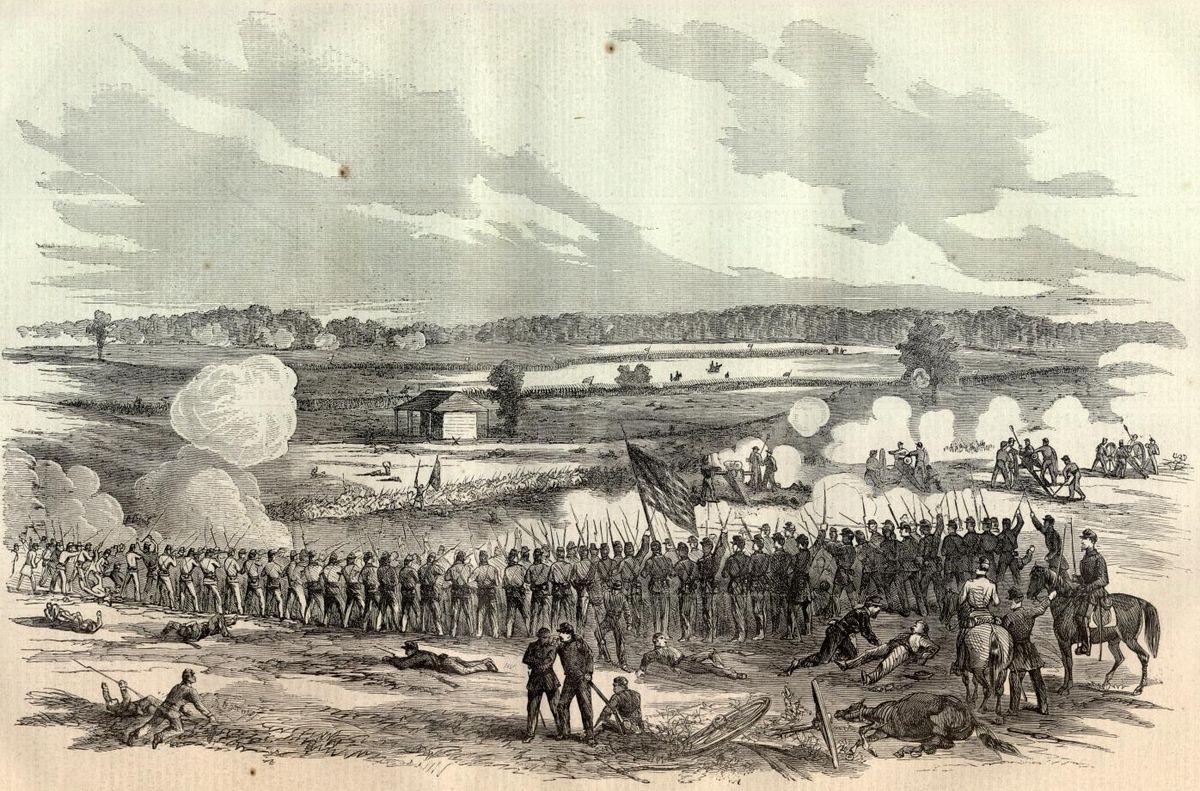

After the Confederates fled Corinth on May 29, 1862, Union forces occupied the city on May 30 and gained a strategic advantage. It was true that Beauregard’s 56,000-man Southern force had entrenched at Tupelo, cutting off the straight route south for the Federals, but with the railways radiating out from Corinth, alternative possibilities were still available. There was no longer any way to defend West Tennessee or the city of Memphis, and thus they both had to fall. And the latter was taken by Northern gunboats on June 6, after the Confederate river flotilla was destroyed.

Strategic dispersal

David Farragut’s navy had been besieging Vicksburg, the final Confederate bastion on the Mississippi, and this victory paved the way to its capture. In the opposite direction, Chattanooga, the entrance to East Tennessee, could be reached through the Middle Tennessee River and the train that followed it. Lincoln, who was worried about what might happen to Unionist supporters, saw this as an enticing target.

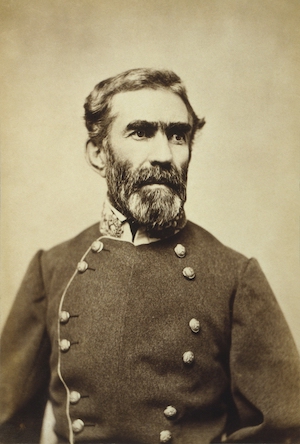

There were approximately twice as many Union soldiers under Henry Halleck’s command as there were under Beauregard’s command in the Southern army. Although initially alarmed by the Confederates’ aggressive behavior at the Battle of Shiloh, Halleck had been somewhat soothed by his opponent’s meekness. In addition, Beauregard gave the Federals the upper hand during the month of June. Relationships were already highly tense after the fall’s incident with President Davis, and his withdrawals from Shiloh and Corinth didn’t help matters. The Cajun’s mild manners were muted even further by the months of illness he’d been fighting. On June 17, Davis stripped Beauregard of his duties after he took a medical leave without informing him. The president of the South removed him from office and installed Braxton Bragg, one of Bragg’s deputies. While not everyone could say the same about the tough nature—made worse by terrible neuralgia—of the President of the Confederacy, Bragg, who commanded one of the Southern army’s wings at Shiloh, got along extremely well with Davis.

Changes were also made at the Northern Command, but for quite different reasons. Lincoln summoned Halleck to Washington on July 23 to take over as commanding general of the army after a vacancy of more than four months and temporary leadership by the War Board. Halleck was the organizer and staff officer Lincoln needed to prepare his overall strategy. John Pope, a protégé of Lincoln’s, was given command of the newly formed Army of Virginia and sent east to participate in the fighting. Ulysses Grant, still hounded by his sulphurous image as a drinker, and Don Carlos Buell, regarded by many to be the winner at Shiloh due to the prompt arrival of his force on the second day of the conflict, were the primary officers in the West after these promotions. Vicksburg was crucial to the success of the “Anaconda Plan” and the command of the Mississippi, but Halleck and Lincoln failed to comprehend what Farragut had seen upon approaching the city with his fleet: that the city’s cliffs rendered it impenetrable by naval attack alone.

It seems that the Northern Command had even managed to convince itself of the opposite. It failed to include the men desperately required to charge the Confederate fortifications on Vicksburg Heights and join Farragut, who was joined in the summer by Commodore Charles H. Davis’ river flotilla. But Lincoln gave in to the political pressures and allure of East Tennessee once again. Since the conflict started, this was his third effort. As a result of the fall of Nashville, the acquisition of Middle Tennessee, and the onslaught against Corinth, attention was diverted from Buell’s tentative attacks in the winter of 1862. Stonewall Jackson’s swift response in the Shenandoah Valley prevented Frémont’s planned spring effort to invade East Tennessee from West Virginia, and Frémont ultimately gave up on the idea. As a result, Lincoln determined that Chattanooga would be the primary target of the western attack this summer. By taking Chattanooga, Northern forces would have access to the only main communication route over the mountains.

An extensive restructuring was implemented alongside this strategic decision. With the dissolution of Mississippi’s military department, the federal forces in the West no longer had a single leader. While Grant remained in charge of the Army of Tennessee, he was granted new responsibilities in the form of a “District of West Tennessee,” which encompassed the Army of Mississippi under the leadership of William Rosecrans, who had replaced Pope. As for Buell, he was given free rein to lead the Army of the Ohio once more, putting him in charge of the operation against Chattanooga. While Grant kept 80,000 troops under his command, he started out with just about 30,000. It became clear, however, that the troops sent to Buell were insufficient. When the Union forces moved into enemy territory, they ran into a new challenge: they needed to leave substantial detachments behind to protect their lines of communication. One of Grant’s divisions was dispatched to Arkansas to seize Helena, while three-quarters of the Army of the Mississippi was sent to strengthen Buell’s. Only 50,000 troops remained under Grant’s command within a matter of weeks, and they were dispersed across the country to protect various railroad connections. The Northern General was put into defensive mode, and he refused to launch any offensive operations over the summer.

Guerilla warfare and cavalry raids

Unfortunately for Buell, the Tennessee River could not be navigated all the way to Chattanooga, thus his almost impenetrable supply line ended at Nashville. Since there was no other direct route from Corinth to Chattanooga, he was forced to rely on the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. It didn’t take long for the Northerners to realize that their enemy might easily sever this line. Mostly unarmed individuals in Tennessee and Alabama banded together to establish “Ranger Partisan” teams that attacked poorly guarded targets, including bridges and train stations. These rebels could demolish an unguarded stretch of track, stack the rails on the sleepers, and light them on fire in a matter of hours. It didn’t take long for the heat to warp the iron of the rails sufficiently to render them useless. Northern’s engineers would need several days to fix the train connection. Before dispersing to their fields, Southerners attacked isolated detachments and supply wagons. On August 6, General Robert L. McCook, one of Buell’s subordinates, was ambushed and murdered.

From the get-go, the Confederates intended to use harassment as a primary tactic. In East Tennessee, Edmund Kirby Smith, who was in charge of defense (and, like Buell, had autonomy of command from Bragg), spread his troops thin to provide a constant but scattered danger to Buell’s supply routes. However, he quickly adjusted his approach. Early in the month of June, under James Negley’s leadership, a scouting group from the Army of the Ohio set out from Nashville in the direction of Chattanooga. Negley’s fast advance on June 7 and 8 was met with an artillery battle, the results of which revealed the vulnerability of the Chattanooga defenders. However, the Northern general was in a vulnerable position and could not afford to be cut off from his rear. The incident acted as a cautionary tale for E.K. Smith, and he eventually withdrew to Murfreesboro. He sent about 20,000 of his men to defend Chattanooga, knowing that if they were to fall, his entire deployment plan would be useless. As a result of this decision, the Confederates abandoned the highly entrenched Cumberland Clause, which controlled the major approach to East Tennessee from the north. It was on June 18 that federal forces arrived.

Even after these early victories, Buell’s progress to the east was slow. By taking over Decatur and then Huntsville in north Alabama, he was able to cut the distance he had to travel to get supplies from Birmingham to Nashville. The Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad just needs a few more miles to complete a second route between Tullahoma and Murfreesboro. However, far from helping Buell, this new circumstance really required him to expand his reach even more. Even with reinforcements, by early August, the Army of the Ohio was spread out over northern Alabama, from Florence to Huntsville, with garrisons also stationed in middle Tennessee. Simultaneously, the Confederacy was testing out a new tactic. After Nathan Bedford Forrest recovered from his severe wound at Shiloh, he was elevated to brigadier general and given command of a cavalry brigade consisting of 1,400 troops. At the same time, a Kentucky native named Colonel John Hunt Morgan assembled a comparable force of 900 cavalrymen, also composed primarily of pro-Southern Kentuckians. Both Forrest’s Tennessee column and Morgan’s Kentucky column were given orders to launch a daring attack deep into territory controlled by the North. While Morgan departed Knoxville on July 9th, the former left Chattanooga on that same day.

On the 13th of July, Forrest encircled the Northern garrison at Murfreesboro, led by his nephew Thomas T. Crittenden. He is Crittenden, the nephew of Senator John Crittenden of Kentucky. The Northern commander had arrived the day before and been caught off guard; nearly all of his 900 soldiers were captured. By obliterating the Murfreesboro terminal, Forrest was able to disable Buell’s access to the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. Morgan, on the other hand, advanced far into Kentucky, seizing 1,200 prisoners and the Northern supply depots in Tompkinsville (July 9) and Cynthiana (July 14). The Southern Command learned invaluable lessons from Morgan’s attack, which was even more spectacular than Forrest’s. The people of the area, especially those in and around Lexington, who had some degree of sympathy for the secessionist cause, had welcomed Morgan and his troops with open arms. Morgan concluded the operation with more men than he had at the beginning because so many volunteers joined the Southern column. Based on these numbers, Davis was confident that invading Kentucky would prompt the state’s population to rally for the Confederacy, and he gave Bragg orders to do just that.

The Confederacy covets Kentucky

Bragg and Kirby Smith got together in Chattanooga on July 31, 1862, to plot their next moves. Bragg suggested that he relocate his army’s headquarters to Chattanooga, with 35,000 troops going there and the remaining 15,000 staying in Tupelo with Earl Van Dorn. Simultaneously, Smith was to lead his own force north to retake the Cumberland Clause and destroy the threat presented by the 10,000 Northern troops who had landed there. After he finished, Smith would go back to join Bragg. The united forces would then march on Nashville in an effort to convince Buell to call off his retreat and force a decisive battle from an inferior position. While Grant was busy trying to reinforce Buell, Van Dorn would conduct diversionary attacks against Grant’s fortifications. The Confederates would not invade (or, from their point of view, free) Kentucky until they had first annihilated or severely defeated the Army of the Ohio.

It was on the basis of a gentleman’s agreement between Bragg and Smith that this intricate strategy, which needed extensive coordination between the numerous forces involved, was carried out. They came to an agreement that, despite Smith’s independence as commander, he would report to Bragg once their troops were combined. Smith was fiercely protective of his autonomy and sought his own success. Davis could have made things much easier if he had placed him directly under Bragg’s command, but he chose not to. On August 13, Smith launched his onslaught from Knoxville, and he wasn’t in a rush to cross the Cumberland Gap. He quickly came to the conclusion that it would be preferable to maneuver to compel the North to vacate it rather than attack it head-on. As a side note, this action would have him enter Kentucky without further delay, giving Smith all the credit for the triumph. The southern commander split his army in two, sending Carter Stevenson to secure the northern stronghold while he himself attacked from behind. Smith achieved success on August 18. Though not totally besieged, the Federal garrison was ultimately compelled to retreat eastward into the mountains, leaving the Cumberland Gap and the rest of the operation ineffective.

Smith didn’t try to hide his motivations from Bragg, which forced the latter to entirely rethink his strategy. On August 27, he informed Van Dorn that he was leaving Chattanooga to carry out the prearranged diversionary operations, with Van Dorn’s possible participation. Bragg decided against advancing on Nashville and instead took a circuitous path over the Appalachians to the north. Getting to Smith in Lexington was now his first priority. Although the Confederate onslaught was hastily put together, it nevertheless managed to spread terror among Union forces. Even though Buell’s army was well to the south, his enemies were between him and Louisville, the primary Northern rear camp in the West. Thousands of recently enrolled volunteers, many of whom lacked the necessary equipment or training, were hastily dispatched to Kentucky. General Horatio Wright was given command of this vast operation, and Buell delegated responsibility for field coordination to an underling named William Nelson. The newly formed “Provisional Army of Kentucky” began consolidating its forces in the state’s eastern capital, Richmond.

However, they were blindsided by Smith’s leading forces, numbering around 7,000 men under Patrick Cleburne. These were the men that Bragg had “loaned” to Smith for the time being. Even though Nelson had not yet arrived in Richmond, Mahlon Manson was in charge of the 6,500 Northerners stationed there. South of Richmond, on the morning of August 29th, cavalry from both sides clashed. As the conflict intensified, the Federals’ reinforcements eventually emerged victorious in the afternoon. Manson was so encouraged by this victory that he charged into battle with his own brigade, despite explicit instructions from Nelson not to attack his still-blue recruits. The conflict didn’t get very intense until after dark, which gave Cleburne a chance to reorganize his soldiers. The Southerners launched their attack at first light on the 30th, driving Manson into hiding. It was a disaster for the Federals when their inexperienced troops broke and fled the battlefield, even with the help of reinforcements and Nelson himself. The “Provisional Army of Kentucky” was nearly annihilated, and more than 4,000 Northerners were arrested (including Manson). Nelson was shot in the thigh. Less than a tenth as many Union soldiers died or wounded as Confederates. Cleburne was one of them; he suffered a superficial facial wound.

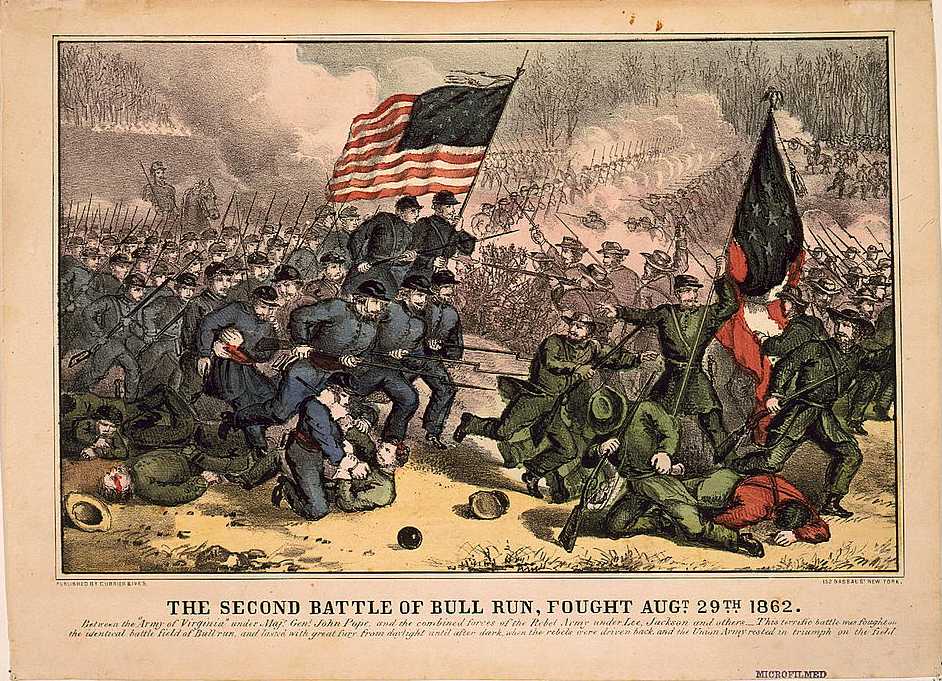

The North was already reeling from the even more devastating loss at the Second Battle of Bull Run when the defeat at Richmond compounded their woes. The Confederates made their way toward Louisville in the west and the Ohio River in the north, seemingly unimpeded. Cincinnatians panicked, and the city’s African Americans were drafted into a “digger brigade” to help construct defenses. In a second attack, the Southern horseman Morgan severed the railroad route between Nashville and Louisville, making it more difficult for Buell to pursue Bragg. The railroad tunnel in Gallatin, Tennessee, collapsed on August 14 after he captured the town. There was a lengthy interruption in service. With this fresh setback, it was no longer clear which of Bragg and Buell would win the race to Louisville first. The invasion of Kentucky in September 1862, on top of General Lee’s assault on Maryland, was the worst month of the war for the Union.

Kentucky occupied

Even as the sun set on the first day of the Battle of Richmond, the advance guard of Smith’s army had made it to Lexington, where they were met with a rousing show of support by the locals. Smith had brought with him a large number of firearms that he planned to give out to Kentuckians who joined his army. His expectations were rapidly demolished in this regard. Secessionist leaders and residents in Kentucky made numerous public vows of support for the Southern cause, but in fact, few were eager to take up weapons immediately. Kentuckians knew that the Southern attack was a “full-scale raid,” as James McPherson has pointed out. Bragg and Smith’s forces were too small, and they lacked the resources to hold the state for long. Therefore, the locals stayed on the sidelines out of caution. Nonetheless, Smith achieved a symbolic victory by capturing Frankfort, Kentucky’s capital, in early September. Then, until Bragg arrived, he went on the defensive, only conducting a few reconnaissance trips toward Louisville and Cincinnati. The only noticeable result of this was the hastening of military preparations in the region by the Northerners.

It was also extremely worrying to see how the military situation in the Union was developing. Lincoln was worried that Buell was several days behind Bragg in the campaign for Louisville, prompting Halleck to often urge the Ohio commander. Bragg physically stood between Buell and Louisville on September 14 when he arrived at the Louisville & Nashville Railroad in Munfordville in central Kentucky. Colonel John Wilder led a force of just 4,000 inexperienced troops to defend Munfordville. When the advance guard from the South approached him, Wilder refused to surrender, and his tiny but well-entrenched garrison successfully withstood the Confederate attack. After losing over 700 troops in the battle, Bragg gradually besieged the city. Wilder and his men managed to hold out for four days, which turned out to be a necessary reprieve. The 16th of September found Buell in Bowling Green, which is roughly 50 miles southwest of Munfordville. Bragg, under pressure to terminate the conflict, scheduled another attack for the next day but gave Wilder one more chance to surrender. When the Northern officer realized he would have to confront the full opposing force this time, he decided it was best to surrender rather than risk the lives of his soldiers.

Bragg now doubted his ability to seize Louisville before his opponent intervened, since he was only one or two days ahead of Buell. Bragg thought he needed Smith’s forces to assault Buell before he could be reinforced by the troops massing in Louisville, despite Smith’s urging to do otherwise. Even when Bragg claimed to obstruct Buell’s path to Louisville, the Northern general refrained from assaulting him out of an abundance of caution. The strategic position of the Confederacy in Kentucky was already complicated by the influx of Federal forces into Louisville and Cincinnati. When Bragg couldn’t make up his mind, he swung his army to the east and arrived at Bardstown on September 22. He reasoned that he had to do this since he owed it to Smith to feed his army, and he needed to join him. The latter was too far away from its Chattanooga base to hope to get supplies via the highways that traversed the Appalachians now that the Federals controlled the railways.

After taking a long detour to avoid meeting Bragg, Buell didn’t get to Louisville until the 26th. But that was enough to end the danger to her safety. After swiftly recovering from his wound at Richmond, William Nelson organized a force that included his army. Nelson, who went by the nickname “Bull” due to his upbeat personality and flowery language, was a staunch Unionist who was quick to infer treason in subordinates who did not do their duties to his satisfaction. Thus, Nelson ran upon General Jefferson Columbus Davis, whose responsibilities he had terminated on September 22. Davis was hurt by Nelson’s comments since, contrary to his surname, he was not a traitor. When the two men finally did meet on September 29 in a Louisville hotel, tensions swiftly escalated. After Nelson smacked Davis, he shot him in the heart with a pistol he borrowed from a buddy. His death robbed the Union of two capable generals at a pivotal period, notwithstanding the fact that Davis was never brought to justice after being freed and continuing his military career.

Bibliography:

- Engle, Stephen D. The American Civil War: The War in the West, 1861-July 1863 (Osprey Publishing, 2001), well illustrated

- Harrison, Lowell. The Civil War in Kentucky (University Press of Kentucky, 2010)

- Penn, William A., Kentucky Rebel Town: Civil War Battles of Cynthiana and Harrison County, (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2016)

- Wooster, Ralph A. “Confederate Success at Perryville,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society (1961) 59#4 pp. 318–323 in JSTOR(University Press of Kentucky, 2001.

- Cotterill, R. S. “The Louisville and Nashville Railroad 1861–1865,” American Historical Review (1924) 29#4 pp. 700–715 in JSTOR

- Harrison, Lowell H. “The Civil War in Kentucky: Some Persistent Questions.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society (1978): 1-21. in JSTOR

- Howard, Victor B. “The Civil War in Kentucky: The Slave Claims His Freedom.” Journal of Negro History (1982): 245-256. in JSTOR