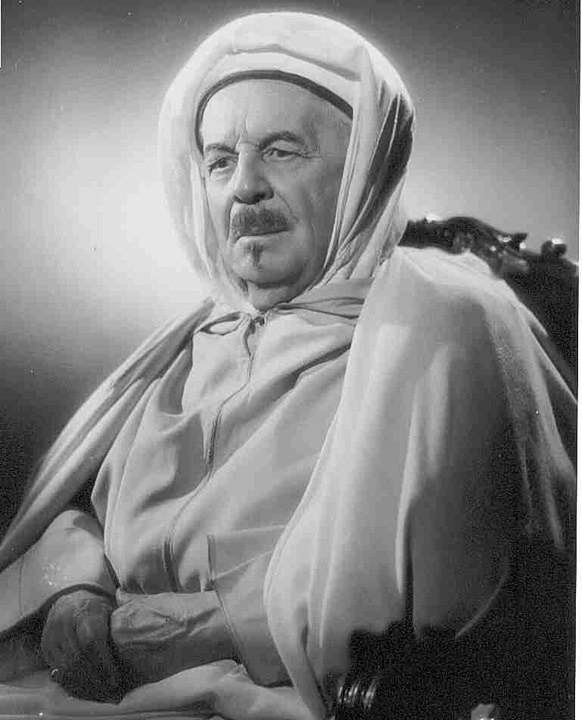

On October 19, 1922, in the early afternoon, a diverse crowd gathered in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, near the Jardin des Plantes. The assembly consisted of soldiers, recognizable by their kepis and the medals adorning their tunics, as well as politicians in top hats. Amidst the sea of dark attire, men wearing hooded white burnouses, a typical North African garment, stood out. Among them was Si Kaddour Benghabrit, who would become the rector of the Grand Mosque. At 2 o’clock, he officially laid the first stone of the building.

One hundred years have passed, and a different crowd enters the entrance leading to the pleasant courtyard. Tourists flock to appreciate the beauty of this place of worship built in an Arab-Andalusian style. As for the faithful, they come to participate in prayers organized several times a day.

When the construction of the Grand Mosque was initiated a century earlier, the French Republic presided over an empire. From the Levant to Africa, the tricolor flag flew over the colonial administrations. In 1922, the memories of World War I were still fresh, with the bodies barely buried, and the Treaty of Versailles, which sealed the terms of Germany’s defeat, was only two years old. The authorities wanted to pay tribute to the sacrifice of Muslim soldiers who had died on the battlefield.

The Great Mosque of Paris is renowned for its stunning Franco-Islamic architectural style. This style combines traditional Islamic elements with French architectural influences, resulting in a unique and visually impressive design.

100,000 African Soldiers Died During World War I

It was after the Battle of Verdun that the military authorities and then the politicians became aware of the sacrifice of these troops. The capture of Fort Douaumont during that terrible battle was an achievement credited to colonial regiments. In total, 500,000 African soldiers, predominantly Muslim, were sent to the French mainland to fight against the army of Wilhelm II. One hundred thousand of them perished, with 70,000 alone at Verdun.

Two men, each representing a form of power, played a decisive role in the construction of the Parisian mosque. First, Marshal Hubert Lyautey. As the French Resident General in Morocco in 1912 and later as Minister of War, the military leader had a deep understanding of Islam and wanted to acknowledge the contribution of the colonies to the victory against the German enemy. During the laying of the first stone, he declared with emphasis, “When the minaret that you are going to build on this square is erected above the roofs of the city, there will be just another prayer rising towards the beautiful Ile-de-France sky, of which the Catholic towers of Notre-Dame will not be jealous.”

The other key figure in this construction was Edouard Herriot. The deputy mayor of Lyon, a member of the Radical Party, authored a parliamentary report advocating the creation of a Muslim Institute in Paris. He wrote, “If the war sealed the Franco-Muslim fraternity on the battlefields, then our country must take pride in marking its recognition and remembrance as soon as possible through actions.“

The bill was unanimously adopted on June 19, 1920. However, Charles Maurras, representing the Action Française, raised objections: “But, if there is an Islamic awakening, and I don’t think there is any doubt about it, a trophy of this Quranic faith on this Sainte-Geneviève hill where all the greatest teachers of anti-Islamic Christianity taught represents more than an offense to our past: it’s a threat to our future.” The protest of this far-right figure did not stop the construction of the Grand Mosque but did lead to a clever workaround.

The Grand Mosque Was Constructed Through a Clever Maneuver

Since 1905, France has been a secular country, and the state cannot finance a place of worship. The construction of the Mosque was entrusted to the association of the Society of Habous and Holy Places, established in 1917 to organize the pilgrimage to Mecca. To circumvent the problem, the association’s headquarters were registered in Algeria, which was then a French department and not subject to the 1905 law. This allowed the state to grant funds. Money was also collected in the Arab colonies.

Thus, the state paid homage to these overseas soldiers through the construction of the mosque. More insidiously, it was also a way for France to assert itself strategically as a colonial Muslim power in a context of imperialism among Europeans and at a time when independence was beginning to be hoped for by anti-colonialists. The first rector of the mosque, Algerian Si Kaddour Benghabrit, served as a dual ambassador: one for Muslims in France and the other for France in the Maghreb.

In 1926, the mosque was ready to receive the approximately 20,000 Muslims living in Paris. For the occasion and for the only time, the call to prayer was launched from the elegant minaret, which rises to a height of 33 meters.

The mosque features beautiful Andalusian gardens, Moorish design elements, and a tall minaret. The prayer hall, adorned with intricate tilework and ornate details, is another notable architectural feature.

These Mosques Also Have Remarkable Histories

- Missiri Mosque in Fréjus: After the war, not all Senegalese colonial troops were repatriated. In the Caïs camp on the outskirts of Fréjus, the riflemen constructed a mosque to combat homesickness in 1928. They took the Djenné Mosque in Sudan (now Mali) as their model. The place served purposes beyond religious worship and included huts and termite mounds to provide the black riflemen with “the illusion of a setting similar to what they had left; they find it there in the evening during endless discussions and the echoes of the drum,” according to Captain Abdel Kader Medemba, the project’s instigator.

- Noor-e-Islam Mosque in Saint-Denis, La Réunion: Noor-e-Islam in Saint-Denis, La Réunion, was the oldest mosque in France until Mayotte was attached. This Muslim place of worship resulted from the efforts of merchants originating from Gujarat, India. “Our mosque will be surrounded by walls and arranged internally to accommodate the sensitivities of other faiths,” they wrote to the governor in 1897. Noor-e-Islam was inaugurated in 1905. Initially modest in size, it was expanded in 1960. Fourteen years later, a fire reduced it to ashes. It was rebuilt in 1979.

- Eyyûb Sultan Mosque in Strasbourg: The Eyyub Sultan Mosque, currently under construction in Strasbourg’s Meinau district, is expected to be the largest in Western Europe, with 9,600 square meters and a capacity to accommodate over 4,000 worshipers. The project sparked controversy in 2021 when the Green Party mayor’s office announced a grant for its construction, made possible through the Concordat. However, Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin accused the Millî Görüs Islamic community, which is behind the project, of “foreign interference.” The association subsequently declined the grant. The mosque’s opening is planned for 2024–2025.