The United States was not prepared to engage in the war in Europe in 1941. Japanese imperialists sought to expand their country’s footprint in the Pacific and Southeast Asia in order to get access to the region’s rich mineral and agricultural resources. Japanese officials understood that they would have to rely on the United States for help. On December 7, 1941, they planned to launch an assault on the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, which ultimately led to American involvement in the conflict.

After racking up a string of victories, Japan was able to assert control over a number of new regions between 1905 and 1942. The dominance of the Japanese was ended during the Battle of Midway in June of 1942. The Japanese put up a valiant fight, but the Americans were better prepared and had a larger army, so they were able to take the Pacific islands one by one. The bombardment and destruction of the imperial fleet in Japan have created a dire situation. After the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, Japan’s surrender on September 2nd was inevitable.

How Did the Pacific War Begin?

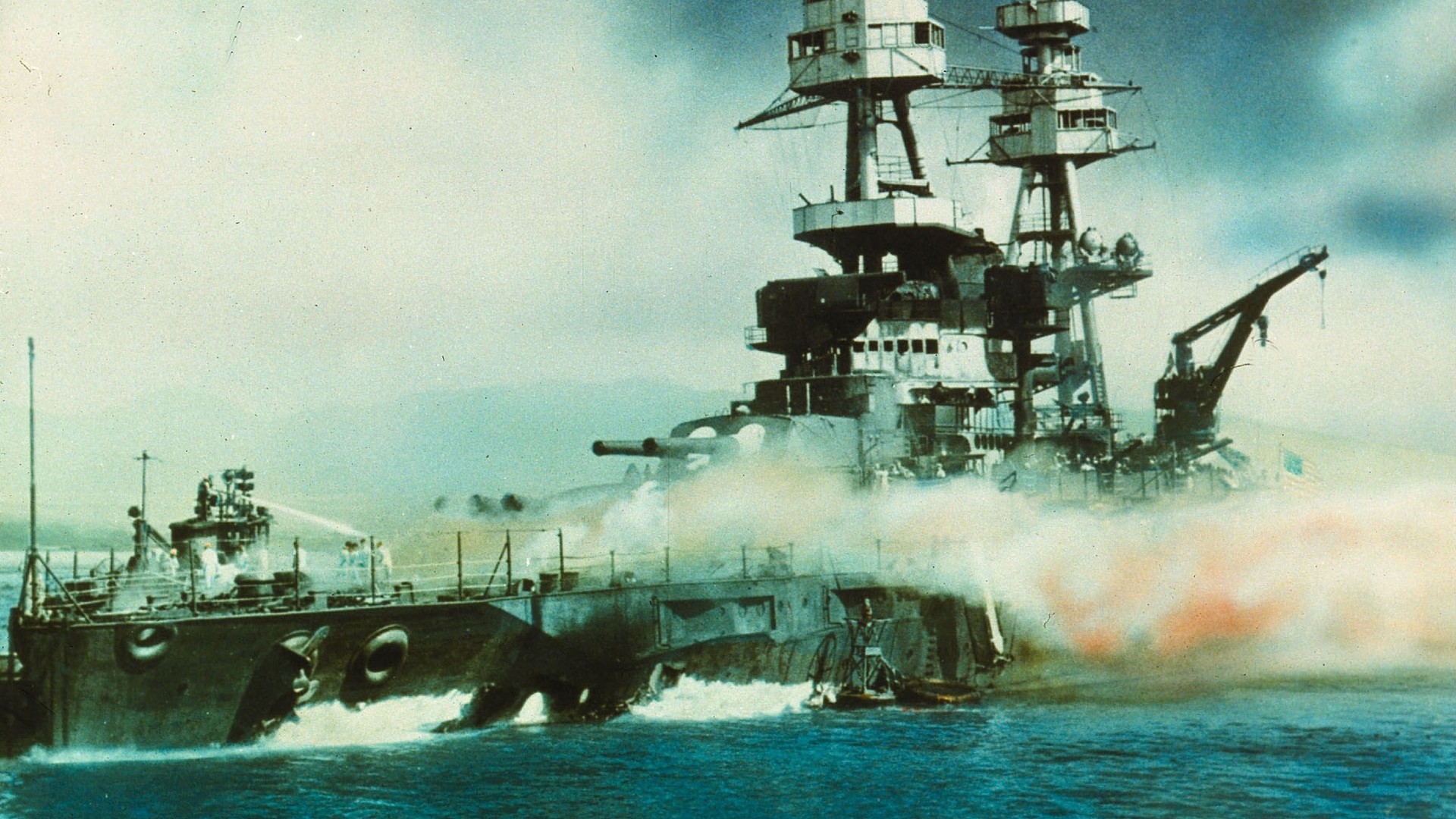

The war in the Pacific began on December 7, 1941, with the Japanese attack on the American base at Pearl Harbor. Japan was planning to expand its territory in the Pacific. In particular, it wanted to conquer the Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore in order to capture the mining, oil, and rubber resources essential to its industry. However, Japan knew that all these territories were under the control of the Western powers and that they would be protected by the United States in particular. The Japanese general staff decided to destroy the bulk of the American fleet, based at Pearl Harbor, an island in the state of Hawaii.

The Causes of the Pacific War

Beginning towards the close of the 19th century, the Japanese Empire actively sought to close the gap between itself and the West in terms of politics, industry, and military might. It adopted an expansionist policy, annexing nearby regions like Formosa and Korea, in order to guarantee a steady supply of raw resources. When the 1930s rolled around in Japan, they were marked by a surge of nationalist sentiment. Invading Manchuria in 1931 and China in 1937, it armed itself with a modern fleet. The Second Sino-Japanese War, which lasted from 1937 to 1945, began at this time.

In the 1930s, tensions between the two countries reached a peak, and the Japanese realized that the United States would not stand idly by while they pursued a program of conquest. Japan joined the Axis powers of Germany and Italy in 1940 and invaded French Indochina. The United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands imposed an embargo on oil and steel on Japan after Tokyo refused to pull out of Indochina and China. It was thought in Japan that the country would soon exhaust its oil supply. Japan’s entry into the war was precipitated by the breakdown of talks with the United States. The destruction of the American fleet was the Japanese military’s first priority in their push to dominate Southeast Asia.

The Different Phases of the Pacific War

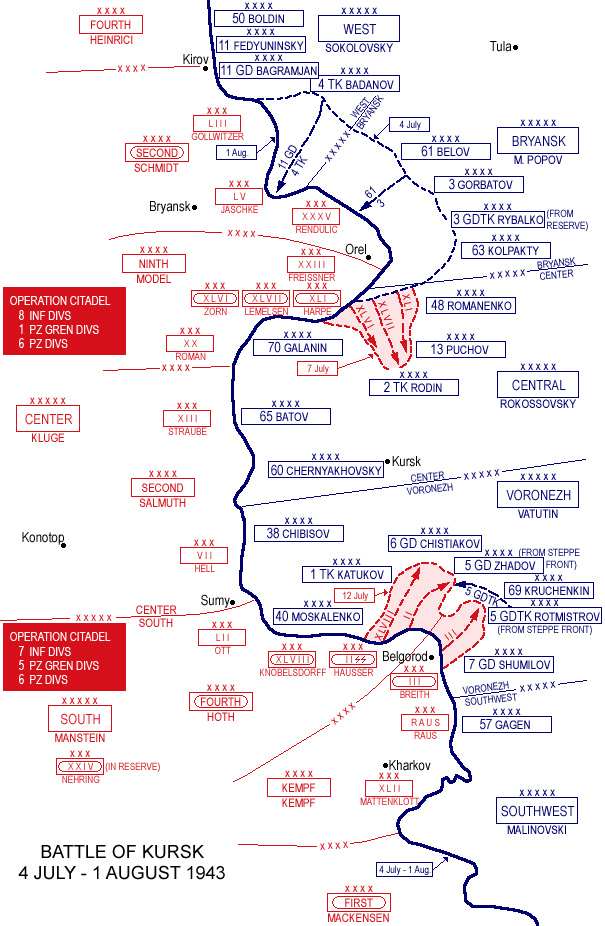

There was an initial phase of the Pacific War in the first half of 1942. The Japanese attacked on several fronts and scored significant successes. They were successful in driving the British out of Burma and capturing the city of Rangoon. They won the Battle of Singapore after having already occupied Malaya. They also took over the islands of Java, Sumatra, and Borneo. While morale was low, the Americans proceeded with the Doolittle Raid (the bombing of Tokyo and other Japanese cities) to show the Japanese that they were vulnerable even on their own land. The Pacific was under Japanese control in the spring of 1942. New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, farther to the south, were the targets of its impending onslaught.

The Japanese high command ordered an assault on the Midway Islands, where the majority of the American resistance was based, at the start of June 1942. The Japanese advance was halted in this engagement, which also marked the beginning of the second phase of the Pacific War. The Japanese Empire suffered a devastating loss in the Battle of Midway (June 4–7) in 1942. As a result, Japanese military dominance in the conflict came to an end. The Americans used their newfound confidence to undertake an onslaught on the Solomon Islands, where they ultimately destroyed the Japanese from August 7, 1942, to February 9, 1943, during the Battle of Guadalcanal.

A number of key islands, including the Marianas and Marshall Islands, were captured by the United States in 1944. The Japanese were suffering a steady setback as the conflict entered its third phase. They were outgunned, outgunned in resources, and outgunned in equipment. In 1945, U.S. forces kept making progress toward Japan. They destroyed a Japanese facility that was reporting American airstrikes back to Japan during the assault on Iwo Jima (February–March 1945). After the Americans won the battle of Okinawa in April and June of 1945, they established a crucial base from which to launch the final attack against the Japanese islands. In the meantime, the war officially concluded in Europe in May.

How Did the Pacific War End?

In June 1945, the United States won the Battle of Okinawa. The American military’s occupation of this archipelago provided a strategic location near Japan from which to launch air attacks and eventually invade the country. American B-29 bombers dropped so many explosives on Japan that 40 percent of the country’s metropolitan areas were devastated. The United States, however, was hesitant to invade the archipelago for fear of losing too many men in the process. In July 1945, during the Potsdam Conference, the Allies requested that Japan capitulate.

If Japan continued to refuse, the Americans threatened to employ a particularly devastating weapon. The Japanese prime minister publicly rejected the ultimatum on July 28. Japan also reached out to the Soviets in an attempt to bargain. Since the United States believed that Japan had rejected the ultimatum and followed through on its threats, it detonated atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945. Japan’s imperial soldiers in Manchuria were annihilated when the Soviet Union declared war on Japan on August 8. Japan’s unconditional surrender on September 2, 1945, signaled the end of World War II.

How Was the Fighting in the Pacific?

The two sides used very different strategies. The Japanese were well equipped, highly disciplined, and motivated, which enabled them to win many battles at the beginning of the Pacific War. Applying a code of honor, they did not hesitate to sacrifice themselves to achieve their goals. This was particularly true of kamikaze pilots, who carried out suicide missions. Battles took place mainly at sea and in the air because of the strategic objectives to be reached, which were mainly islands. Thanks to its powerful economy, the United States mass-produced military equipment. In the end, the American ships and aircraft outnumbered and outperformed the Japanese models.

By 1942, the Japanese forces had lost many ships and aircraft, which they were unable to replace. American submarines sank the majority of Japanese merchant ships, which prevented Japan from refueling. In addition, the Americans bombed Japanese cities and industries in 1944, which had devastating effects on both the economy and the morale of the Japanese. While the Americans advanced in the Pacific, the Japanese adopted a defensive strategy. On the islands, they retreated inland and preferred to die rather than surrender, which cost the American army many casualties. Outnumbered, the United States launched offensives on the strategic islands, such as Iwo Jima and Okinawa, to set up the starting bases for air raids against Japan until the final victory.

How Many People Died in the Fighting in the Pacific?

About 1,750,000 Japanese troops were killed during the Pacific War. The United States was responsible for the deaths of almost one million Japanese people due to its bombing campaign. About 106,000 American troops died, and another 250,000 were wounded. Roughly 8 million civilians died in the nations Japan conquered. The casualties from the Sino-Japanese conflict are not included in these calculations. The Japanese committed war crimes in the captured countries, including the enslavement of numerous women as sexual slaves for the military. War prisoners from the United States, Australia, and Britain were killed in large numbers on death marches and on construction projects like Burma’s infamous Death Railway. About 10,000 Americans and between 77,000 and 110,000 Japanese died in the bloodiest fight, the Battle of Okinawa.

Results of the Pacific War

After their capitulation, Japan lost all of the territory they had occupied since 1895. Because of the American occupation until 1952, it embraced Western culture. Women’s suffrage and the end of the aristocracy were two of the most significant societal shifts of the time. The fall of the Japanese Empire may be traced back to 1947, when Japan accepted a new constitution at the behest of the United States. In the nation, a constitutional monarchy was established. After the Japanese occupation ended, independence movements sprung up in former French and British territories. Western powers were unable to retake their former colonies, leading to the independence of nations like Indochina, Indonesia, India, and Malaysia. Since 1910, Japan’s occupiers in Korea lived in two separate halves. Chinese forces reclaimed Taiwan and Manchuria.

Timeline of the Pacific War

September 25, 1931: Japanese conquest of Manchuria

In the 1930s, nationalist and expansionist sentiment drove Japan’s desire to catch up with the West. The 1929 Great Depression had a significant impact on its economy, and it yearned for access to Manchuria’s abundant resources. The Japanese invaded Chinese land on September 18th, 1931, using the Mukden event as an excuse. Without any opposition from Chinese forces, the Japanese army from Guandong was able to easily conquer Manchuria. The Japanese quickly captured the provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning. At a later date, Manchukuo, a vassal state of Japan, was founded.

July 7, 1937: Beginning of the Sino-Japanese War

Even though they already ruled Manchuria, the Japanese wanted to rule all of China. The Kuomintang and the Communists fought a bloody civil war in China. The Japanese had a justification for invading China, and the Marco Polo Bridge tragedy provided one. However, the outbreak of war did not occur until July 28, 1937. During this conflict, Japan seized a sizable portion of China, stretching from the country’s northeast to its far eastern provinces. Tens of millions of lives were lost before the conflict finally ended in 1945.

Tonkin was occupied by the Japanese on September 22, 1940

The French Indochina Railroad helped supply the Kuomintang while they were at war with Japan. Cutting off the Chinese from their supply was crucial for the Japanese. They sent a last demand to France, saying that they must open the Tonkin Strait to the Japanese forces. Having just been vanquished by Germany, France capitulated to Japan’s demands. However, the Japanese Guandong force had already reached Indochina by the time the treaties were signed. In a single day, the French army was completely routed.

September 27, 1940: Signature of the Tripartite Pact

As part of the Tripartite Pact, Japan collaborated with Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler and Fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini. As a result, it supported the Axis powers in their conflict with the Allies, which included the United States and the United Kingdom. Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia were among the subsequent signatories to the treaty. The zenith of the Axis powers was in 1942, before they began a long and painful decline.

December 7, 1941: Attack on Pearl Harbor

Hawaii was home to the American base at Pearl Harbor. The destruction of the American fleet was a top objective for the Japanese, who were hoping to expand their empire into the Pacific. A total of 183 Japanese planes left their aircraft carriers at 6:00 a.m. on December 7th, 1941, on a mission to attack Pearl Harbor. The initial attack on the American battleships began at 7:53 a.m. At 8:30 a.m., a second swarm of 167 planes landed. At 9:45 a.m., the attackers called it quits. In the United States alone, about 2,400 people lost their lives. Numerous planes were missing, and several ships were either sunk or severely damaged.

December 8, 1941: The United States declared war on Japan

Roosevelt, as President of the United States, declared war on Japan after the Japanese assault on Pearl Harbor. Although the Tripartite Pact with Japan did not require it, Italy and Germany declared war on the United States. World War II was fought on two fronts instead of one once the United States entered the conflict, launching a second front in Western Europe to defeat Nazi Germany.

December 25, 1941: Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese

The Japanese invaded the British colony of Hong Kong a few hours after their assault on Pearl Harbor. They fought the Japanese for 17 days despite being outnumbered. British, Canadian, and Indian forces (17,000 men against 52,000 Japanese) and Hong Kong’s governor signed an act of capitulation with the Japanese on December 25, 1941. Over 4,500 defenders were killed in the Battle of Hong Kong.

The Solomon Islands campaign kicked off in January 1942

The United States and Australia began their Solomon Islands war two months after the Americans’ victory at Midway. The purpose of this effort was to ensure that the United States, Australia, and New Zealand could all communicate with one another. This war was fought both on land and at sea. The American victory in the Battle of Guadalcanal was the campaign’s most well-known engagement. Japan was ultimately defeated, and the operations ended in August 1945.

January 11, 1942: The Japanese invaded and occupied the Dutch East Indies

With the United States at war, Japan had an urgent need for oil. But it wasn’t producing any, and it could not be imported either. After conquering Malaya, the Japanese moved on to the oil reserves of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). With assistance from the armed forces of the Netherlands, Australia, the United States, and Great Britain, Japanese forces invaded the Dutch East Indies in December 1941. In 1943, the Japanese won this war and held the region until 1945.

January 15, 1942: Chinese victory over the Japanese at the third battle of Changsha

The city of Changsha, in the province of Hunan, was a strong point of resistance for the Japanese when they captured a large portion of China. General Xue Yue led an army of 300,000 troops to defend the city. On December 24, 1941, the Japanese launched an unsuccessful assault with 120,000 soldiers. After failing to achieve their goal on January 15, 1942, they surrendered to the Chinese.

The Doolittle Raid, 18 April 1942

With the Pacific under Japanese control in April 1942, American spirits were at an all-time low. But the Allies wanted the Japanese to know that victory was still out of their reach. To do this, they plotted a bombing attack on Japan. As a result, the Japanese knew the Americans couldn’t attack their country since no American base was near enough. Lt. Col. Doolittle’s operation showed the Japanese they were mistaken. The B-25 bombers from the United States were successfully launched from the aircraft carriers and struck Tokyo for a short period of time.

May 4, 1942: Battle of the Coral Sea

Australia and the United States fought together for four days against Japan in the first naval air combat, which ended on May 8, 1942. Disputes broke out between Australia, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands in the Coral Sea. An aircraft carrier, a destroyer, and a tanker all went down for the Allies. A light aircraft carrier, a destroyer, and numerous smaller ships were lost from the Imperial Navy’s side. Even though the Allies suffered more casualties, the Japanese were hampered in their preparations for the subsequent Battle of Midway.

June 7, 1942: American victory in the Battle of Midway

Japanese troops at war with the United States sought to eliminate any remnants of the American naval aviation forces that had survived the first assault on Pearl Harbor. To defeat the American fleet, the Japanese intended to entice it to an assault on the Midway Islands, located to the northwest of the Hawaiian archipelago. The Americans discovered the operation, though, as a result of the Japanese communications’ interception. Moreover, the Imperial Navy was unable to gauge the strength of the opposing fleet owing to the absence of a proper reconnaissance mission. Japan lost four aircraft carriers and a heavy cruiser in the Battle of Midway, which started on June 4, 1942.

August 7, 1942: Marines land at Guadalcanal

The United States and its allies landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida as part of the Solomon Islands campaign against Japan. Protecting the vital communications link between Australia, New Zealand, and the United States was a shared priority. Over time, the plan was to storm the Japanese naval station in Rabaul. The Japanese attempted to reclaim islands that were then in Allied hands during the Battle of Guadalcanal, which lasted from August 7, 1942, to February 9, 1943. The attempt was unsuccessful.

August 9, 1942: Japanese victory at the Battle of Savo Island

The Japanese forces retaliated at Savo Island after the Allied landings on the Guadalcanal Islands. The Allies were in the midst of a landing operation when they were suddenly attacked in the middle of the night. The Imperial Japanese Navy sank three Allied heavy cruisers with very few casualties on either side. Despite their seeming win, the Japanese withdrew from the operation without destroying the cargo ships. The Allies were able to fortify their strongholds in the Solomon Islands because of this strategic blunder.

Blackett-Solomon Islands Campaign Battle, 6 March 1943

A number of Japanese outposts remained in the Solomon Islands after the American victory at Guadalcanal. On Kolombangara, they stationed a sizable army garrison. On March 6, 1943, two Japanese destroyers were en route to the Blackett Strait to provide supplies to the garrison when they ran into American vessels. The combined efforts of three American cruisers and three American destroyers sank the two Japanese ships.

March 27, 1943: Battle of the Komandorski Islands

The Japanese invaded American territory on the islands of Attu and Kiska during World War II in the Pacific. The Americans saw a Japanese resupply ship near the islands and decided to attack. A Japanese naval force encountered two American cruisers and four destroyers on March 27, 1943, near the Komandorski Islands. The Japanese fleet consisted of four cruisers, four destroyers, and two supply ships. The fight was a draw for both fleets. After that, the Japanese decided to send submarines to the two islands.

Battle of New Georgia, Solomon Islands Campaign, June 20, 1943

In 1942, the Japanese invaded the Solomon Islands and seized New Georgia with 10,500 soldiers. They anticipated the imminent arrival of American forces. With the aid of their allies from Australia and New Zealand, American troops launched an assault on June 20, 1943. When the Allies attacked, they outnumbered the Japanese three to one, and the Japanese quickly capitulated. However, they were able to successfully escape by boat back to the Rabaul outpost.

July 6, 1943: First Battle of the Gulf of Kula, Solomon Islands Campaign

In the Gulf of Kula, Solomon Islands, during the night of July 5–6, 1943, a group of American destroyers, Task Force 18, intercepted a Japanese supply. The Allies’ nickname for the nightly supply runs made by the Imperial Navy was “Tokyo Express.” Ten Japanese destroyers were at their disposal. Three American cruisers and four destroyers came up in a line and sank two Japanese ships, killing 324 people, including Vice Admiral Akiyama. The Japanese, however, struck back by sinking the USS Helena, a cruiser. The battle’s result was up in the air.

13 July 1943: Second Battle of Kula Gulf, Solomon Islands Campaign

The Americans discovered the Japanese Navy’s midnight “Tokyo Express” supply operation in the Gulf of Kula. The Americans were trying to defend against this supply, but the Japanese were able to identify them almost immediately. Nonetheless, they were successful in sinking the Japanese light cruiser, which went down with Vice Admiral Isaki on board.

7 August 1943: Battle of the Gulf of Vella, Solomon Islands Campaign

It was during the night of August 6–7, 1943, when six American warships discovered four Japanese destroyers in the Gulf of Vella. The Imperial Navy often resupplied its bases in the middle of the night. The Allies’ name for this strategy was “Tokyo Express.” Three Japanese warships were sunk as the Americans conducted a surprise torpedo attack. Just one slightly damaged Japanese ship made it out of there.

18 August 1943: Battle of Horaniu, Solomon Islands Campaign

The Japanese army had to withdraw from the central Solomon Islands in August of 1943. Twenty landing boats and numerous additional ships were sent, with four destroyers providing security. Near the island of Vella Lavella, American planes discovered the convoy and launched an assault. The Americans sent in four destroyers and opened fire on the Japanese, damaging two of their own ships and destroying four support vessels. The Imperial Japanese Navy won because the United States Navy had no losses while failing to stop the departure of nine thousand Japanese soldiers.

October 7th, 1943: Battle of Vella Lavella, Solomon Islands Campaign

When the Japanese defenses on Kolombangara proved too strong, the Americans shifted their focus to Vella Lavella. On August 15, 1943, nearly 9,600 American and New Zealander forces arrived on the island, driving the Japanese back toward the island’s northern tip. The island’s 700 or so Japanese forces left on October 9, allowing the Allies to turn it into an aviation base for use in Rabaul.

November 2, 1943: Battle of Augusta Bay, Bougainville Campaign

The Pacific War progressed with the retaking of more and more islands by American soldiers from the Japanese. On November 1st, 1943, U.S. forces arrived on the island of Bougainville. Japanese soldiers reacted with airstrikes on Rabaul. The Japanese Imperial Navy sent four cruisers and six destroyers into Empress Augusta Bay on November 2. An American force consisting of eight destroyers and four cruisers met the Japanese fleet. As a result of American efforts, two Japanese ships were destroyed: one cruiser and one destroyer.

November 23, 1943: The Americans liberate Tarawa

The United States had an interest in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands as early as July 1943, realizing that having access to these islands would enable them to establish air bases from which to exert pressure on Japan. On November 21st, the United States launched a 35,000-man assault on the Gilbert Islands atoll of Tarawa. The 2,600 Japanese troops who had taken up positions on the island put up a stiff struggle. More than a thousand American troops were killed in only two days, and another two thousand were injured, yet the Americans nevertheless managed to take control of Tarawa. Only seventeen men made it out of the Japanese jail camp alive.

November 26, 1943: Battle of Cape St. George, Bougainville Campaign

As a result of the American invasion, the Japanese were forced to strengthen their position at their base at Buka, located on the island’s western coast. They sent five destroyers from Rabaul and landed 900 troops and their gear. The U.S. Navy’s radar caught the Japanese returning fleet. Five US Navy warships launched an assault on the Japanese off Cape St. George. Three ships from the Imperial Japanese Navy were destroyed, although no lives were lost on the American side. The Solomon Islands naval campaign ended with this fight.

The “Ichi-Go” Operation began on May 9, 1944.

The “Battle of Henan, Hunan, and Guangxi” is another name for this operation in China. This was an assault on Japanese territory. The Japanese wanted to take control of the U.S. air sites in China’s southeast. Japan’s 400,000-man army successfully invaded China with support from the U.S. Air Force and advanced into Indochina. They were successful in occupying a considerable area. In spite of this, the US relocated its air bases to the Mariana Islands, nullifying the advantages of the “Ichi-Go” operation.

The Saipan Battle began on June 15, 1944

Having retaken the Solomons, Gilberts, and Marshalls, the Allies next assaulted the Marianas, bringing them closer to Japan. Many Japanese citizens lived on these islands despite the presence of 31,000 Imperial Army troops tasked with defending them. After landing on Saipan on June 15, 1944, with 70,000 soldiers, the Americans were able to capture the island three weeks later, on July 1. This victory came at the cost of 3,426 American lives and approximately 13,100 wounded. Twenty-four thousand Japanese troops perished. Roughly five thousand Japanese soldiers killed themselves rather than surrender to the Americans.

June 19, 1944: Battle of the Philippine Sea

Admiral Ozawa’s mobile force launched an assault on the U.S. fleet as the Americans prepared to invade the Mariana Islands and seize them. The Japanese lost three ships and half their planes in this operation (395 aircraft were shot down). As opposed to the Imperial Japanese Navy, the United States Navy only lost 124 planes and zero ships. Due to a severe shortage of aircraft and pilots, the Japanese naval aviation forces were wiped out in the Battle of the Philippine Sea and never recovered.

The Battle of Guam began on July 21, 1944

The United States military needed to seize control of the Mariana Islands in the midst of the Pacific War in order to set up strategic bases for attacking Japan. Guam, an American territory that the Japanese took over in December 1941, was not too far away. Three thousand and six hundred American soldiers arrived on the island on July 21, 1944, to reclaim it from the Japanese. In 1944, on August 10, the Japanese surrendered, and Guam was freed. Nearly 1,800 Americans were killed in the conflict, while just a few of the 18,600 Japanese soldiers were killed or wounded.

July 24, 1944: Battle of Tinian

The Americans began their conquest of the Mariana Islands by landing on Tinian, where 9,000 Japanese forces had dug in for the long haul. Between July 24 and August 1, 1944, American forces took control of the island. About 2,500 soldiers were saved thanks to the efforts of the Japanese navy. The United States lost 328 men at the Battle of Tinian, while the Japanese lost almost 6,000. After that, the United States military built the biggest air base in the world on the island of Tinian. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were launched from there.

October 27, 1944: The Nipponese navy was broken in the Gulf of Leyte

The United States military operation in the Philippines began that year, in October. The archipelago’s freedom from Japanese rule was their primary ambition. The United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy engaged in massive naval combat in the Gulf of Leyte off the coast of the Philippines from October 23rd to October 26th, 1944. Many historians rank this conflict as the greatest naval engagement ever fought. There were a lot of ships in play, with the Japanese fielding four aircraft carriers, seven battleships, and thirteen heavy cruisers, and the Americans deploying thirty-four aircraft carriers, twelve battleships, and twenty-three cruisers. The United States Navy ultimately prevailed in four battles against the Imperial Japanese Navy, which ultimately ceased to exist as a fighting force.

November 24, 1944: Bombing of Tokyo

From India and China, the United States began bombing Japan in 1944. The first American air strike occurred on November 24, 1944, over the Mariana Islands, which the United States had just liberated from the Japanese. With incendiary bombs in tow, 88 B-29 bombers headed towards Tokyo. Flying at an altitude of 33,000 feet (10,000 meters) meant that few of them really made it to their destinations. This was the first in what would be a lengthy string of attacks on the Japanese archipelago.

February 4, 1945: Opening of the Yalta Conference

The three leaders of state, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin, convened at Yalta, Crimea, from February 4–11, 1945. For a whole week, as Japan and Germany teetered on the brink of defeat, the top Allied leaders deliberated the war’s consequences. They wanted to finish the war as quickly as possible, determine what would happen to Europe following the collapse of the Third Reich, and establish the basis for a whole new global order. Stalin won the summit because he was able to negotiate concessions from the Western powers. After that, he had the power to establish Soviet dominance over Eastern European nations.

The Battle of Iwo Jima began on February 23, 1945

The United States was drawing nearer to Japan and would soon be able to unleash air strikes against the archipelago from its bases in the Mariana Islands and the Philippines. But despite this, the island of Iwo Jima in Japan tipped off the Japanese anti-aircraft defenses. 22,000 Japanese soldiers were watching over American troops as they started the conquest of Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945.

The United States military invaded the island with 70,000 soldiers and quickly established their dominance. The American flag was hoisted on top of Mount Suribachi. Roughly 7,000 American servicemen lost their lives at Iwo Jima between February 23 and March 26, 1945. With 20,703 dead and 1,152 missing, the Japanese army was almost wiped out.

Tokyo was bombed on March 9, 1945

If the American bombs on Japan started in 1944 and continued until March 9 and 10, 1945, the latter was the worst. 325 B-29 warplanes unleashed tons of incendiary bombs on Tokyo as part of Operation “Meetinghouse.” 100,000 Japanese people lost their lives because of the assault. Over a million individuals were displaced, and many of them became homeless. The number of victims from this bombing exceeded that of the Hamburg and Dresden attacks combined.

March 9, 1945: Japan takes control of Indochina

Japan was worried that the Allies would launch an offensive via Indochina, which would be a catastrophic military move. Beginning in 1940, Japanese forces occupied a portion of the country, while the French maintained sovereignty over the remaining territory. The French Committee for National Liberation, which was in charge of the latter group, wanted to put together a fighting force to drive the Japanese out. The Japanese army launched its offensive on March 9, 1945, with 95,000 troops. The Annamese added to the French’s 18,000 troops, making the total French force 42,000. The Japanese eventually won out and ruled all of Indochina. Some 37,000 French and Annamite captives were taken by the Japanese and killed in prison camps.

March 10, 1945: Proclamation of independence for Cambodia

Once a protectorate, Cambodia was annexed to French Indochina in 1945. When the Japanese invaded Indochina, they urged King Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia to declare independence on March 10, 1945. Son Ngoc Thanh, a nationalist, was installed as the country’s leader. When the Japanese were defeated, Cambodia became a French protectorate. Independence was not achieved until 1953.

March 27, 1945: Beginning of the “Famine” operation

As Japan continued to refuse to submit, the United States implemented “Operation Starvation.” The goal was to block Japanese commercial ships and soldiers from using Japanese waterways. U.S. Air Force aircraft dropped the mines. Around 670 Japanese ships were destroyed, and the country’s last maritime lines were abandoned.

Okinawa was assaulted by the United States on April 1, 1945

After their success at Iwo Jima, the Americans shifted their focus to Okinawa. With this island in their possession, they could make their decisive assault on Japan. Seventy-seven thousand Japanese troops had dug in there. Between 183,000 and 250,000 American troops arrived on Okinawa after losing many ships to kamikaze raids. The Japanese put up a ferocious fight for weeks because they considered surrendering an insult to their pride. The United States military eventually overran the island, but not before losing almost 20,000 men. Nearly eleven hundred people lost their lives at the Japanese concentration camp.

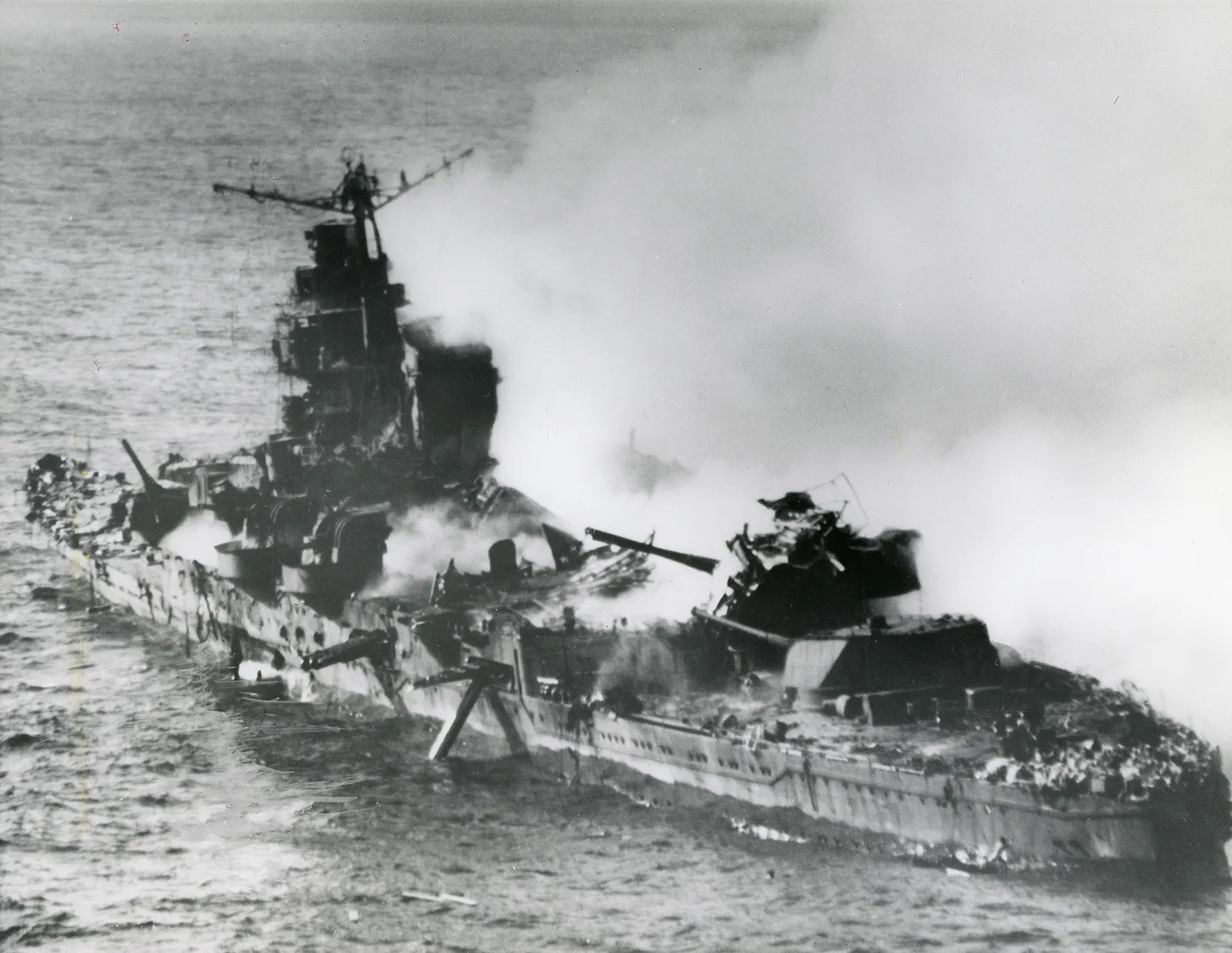

April 7, 1945: Operation “Ten-Go”

In the middle of the invasion of the island of Okinawa, the Americans were at the gates of Japan. The Japanese decided to launch “Operation Ten-Go” to assist the troops defending Okinawa with a squadron dominated by the “Yamato”, the largest battleship in the world. They hoped to fight their way through the American ships and then beach the “Yamato” on the coast to use it as a coastal battery. The operation was a failure because the Japanese had no air support, and American fighters quickly destroyed their squadron. 3,700 Japanese sailors died in the battle.

May 8, 1945: End of World War II in Europe

The Allies defeated Germany in Europe. On May 7, 1945, the German top brass signed their surrender at Eisenhower’s headquarters in Reims. The fighting had to stop on May 8 at 11:01 p.m. Having defeated the Germans on the eastern front, Stalin demanded that the German generals sign another surrender in Berlin. The act was signed on May 8 at 11:01 p.m. Berlin time (May 9 at 1:01 a.m. Moscow time). While World War II was over in Europe, it continued in the Pacific until Japan surrendered.

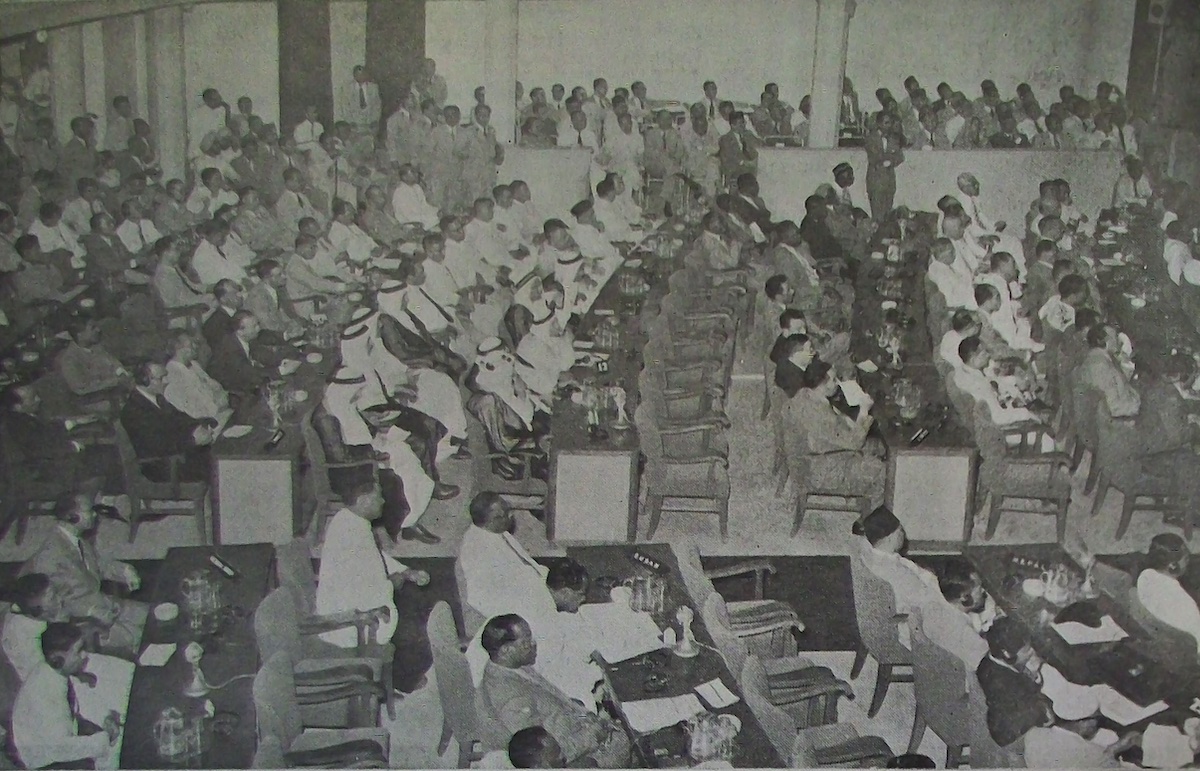

July 17, 1945: Potsdam Conference

After the defeat of Germany, the Allied representatives, Stalin (USSR), Churchill (UK), and Truman (USA), met in Potsdam from July 17 to August 2, 1945. The aim of this conference was to decide the fate of the defeated in World War II, namely Germany, Italy, and Japan, even if the latter had not yet surrendered. The agreements included the demilitarization and occupation of Germany by the Allies, as well as the confiscation of Italian colonies in Africa. Japan received an ultimatum: it was ordered to surrender, or it would suffer “rapid and total destruction.”

August 6, 1945: Atomic bomb on Hiroshima

After issuing an ultimatum to Japan, the Americans carried out their “threat” by dropping an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. The goal was not only to force Japan to surrender but also to intimidate the Soviets. On August 6, 1945, the “Enola Gay” bomber dropped the “Little Boy” bomb, which exploded at an altitude of 1900 ft (580 meters). Fires broke out all over the city after the explosion. The bombing killed between 70,000 and 140,000 people.

August 8, 1945: The USSR declared war on Japan

The entry of the USSR into the war against Japan, three months after the surrender of Germany, was part of the agreements signed by Stalin at the Yalta conference. The Soviets invaded Manchuria, which Japan had been occupying, after the declaration of war on August 8, 1945. Soviet strength reached 1.5 million men. On August 16, the Red Army made its junction with the Chinese army, encircling the Japanese troops. The offensive ended on September 2, 1945. In the meantime, the Soviets took the opportunity to occupy Sakhalin Island, the Kuril Islands, and northern Korea.

August 9, 1945: Atomic bomb on Nagasaki

After dropping the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the Americans sent a second ultimatum to Japan. However, Emperor Hirohito did not respond, hoping to negotiate with the Soviets. The Americans then decided to drop an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Nagasaki. The “Bockscar” bomber was the “Fat Man” bomb. The bombing caused the deaths of 60,000–80,000 Japanese.

September 2, 1945: Japanese surrender

On August 14, 1945, Japan surrendered unconditionally, five days after the bombing of Nagasaki. The next day, Emperor Hirohito announced his surrender to his people during a radio broadcast. The official ceremony of the surrender of Japan took place on September 2 aboard the “USS Missouri”, in the presence of General MacArthur. The Second World War was officially over. The Americans occupied Japan until 1952.

May 3, 1947: A New Constitution in Japan

Two years after the end of World War II, Japan adopted a new Constitution. Approved by the Diet and proclaimed by the Emperor, it established a parliamentary regime, close to the European constitutional monarchies. It was based on three principles: national sovereignty, the guarantee of fundamental human rights, and pacifism. Thus, by Article 9, Japan renounced war and committed itself to not maintaining an army. The interpretation of this article is still the subject of many controversies.

Bibliography:

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin; Bou, Jean (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Second ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195517842.

- Drea, Edward J. (1998). In the Service of the Emperor: Essays on the Imperial Japanese Army. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1708-0.

- Takemae, Eiji (2003). The Allied Occupation of Japan. Continuum Press. ISBN 0-82641-521-0.

- Toland, John, The Rising Sun. 2 vols. Random House, 1970. Japan’s war.