How did Latin America become independent and what were the eventual outcomes? The origins of the South American independence movements may be traced to slave uprisings on plantations in the Caribbean and the northern region of the continent in the 18th century. Spanish American wars of independence lasted between 1808 and 1833 and the young general Simon Bolivar played a crucial role in the movement. Spain’s colonization of South America had its origins in Christopher Columbus’ landing on the continent in 1498 and the influx of explorers and colonizers who followed in his footsteps.

- The Background

- How Did the Latin American Independence Movements Begin?

- What Inspired Simon Bolivar?

- How Did Latin America Develop?

- The Timeline of the Latin American Independence

- The Slave Who Liberated Haiti: François Toussaint Louverture

- Bolivarian Revolution and Simón Bolivar

- The Republic of Gran Colombia

- The Liberation of South America

The Background

In June 1494, with the Treaty of Tordesillas, it was agreed that all lands discovered in the west of a specific longitude belonged to Spain. The new lands east of this longitude would belong to Portugal. This treaty put a vast territory that would later be known as “Brazil” into Portuguese territory.

At first, the newcomers gained absolute control over the gold, silver, and textile-rich lands they conquered. Soon, however, Spanish rule tightened controls and monopolized all trade. This would last for more than 300 years until the Spanish were finally driven out by rebel forces across the continent.

How Did the Latin American Independence Movements Begin?

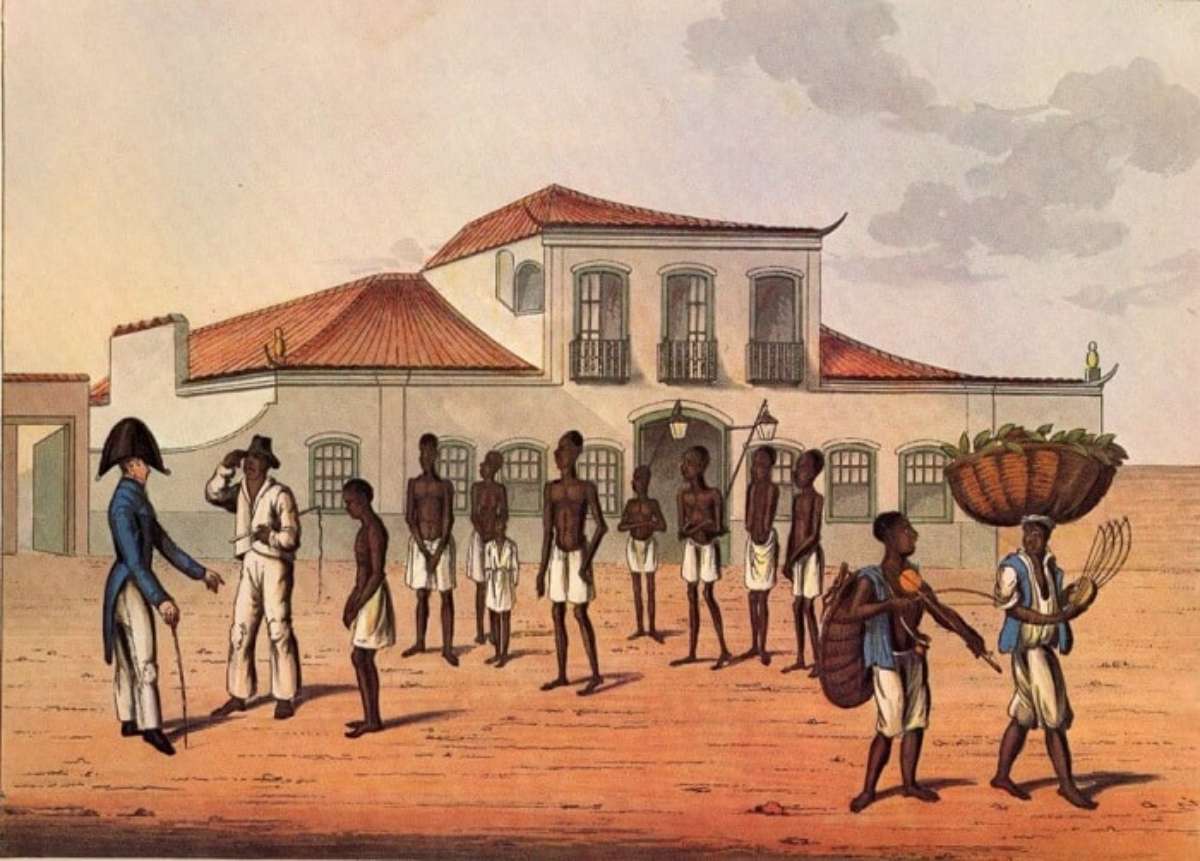

Spain’s reforms in the 18th century tightened the country’s ties with its colonies. But these new reforms also led to increased tensions between the Creoles, the Spaniards born in America, and the Spanish-born Peninsulares.

The Creole elite resented trade bans that prevented them from trading with any country outside Spain. As the European demand for sugar, coffee, tobacco, and leather grew, the Creoles realized that their country’s enormous wealth was being exploited by Spain. They were also unable to hold positions of authority which were largely reserved for those born in Spain.

The advances in education created an enlightened Creole class, which led to the “Enlightenment thinking” of 18th-century Europe. As the Creoles increasingly felt that they owed more loyalty to their country of birth than to Spain, a new concept of Americanism was born.

Two leaders emerged from this spreading revolutionary idea: Francisco de Miranda and Simon Bolivar, both influenced by liberal ideas in Europe and North America. In 1874, Miranda traveled to New York, where he expressed his dream of freedom and independence for all of Hispanic America. The American Revolutionary War and the French Revolution further fueled Creole unrest. In 1791, a slave uprising began in Haiti and culminated in Haiti’s independence from France in 1804. Napoleon Bonaparte‘s invasion of Spain in 1808 shook the power of the Spanish monarchy and became a galvanizing factor for independence.

The independence movement was unstoppable and by 1810 Creole revolutionaries were in revolt all over Spanish America.

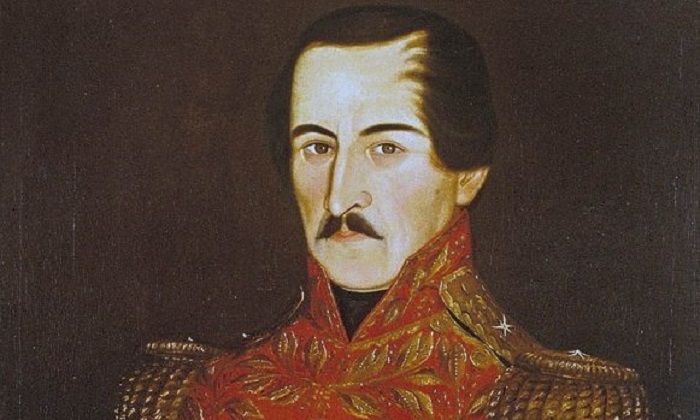

What Inspired Simon Bolivar?

The son of a Venezuelan aristocrat, Simon Bolivar was born in Caracas on July 24, 1783. He was raised by his uncle and educated by a series of tutors. One of them, Simon Rodriguez, introduced him to the ideas of 18th-century liberalism. By the age of 24, Bolívar was already part of the Latin American independence movements. In 1806, a coup led by Francisco de Miranda ended in disaster. But in 1810 a junta in Caracas took advantage of Spain’s defeat at the hands of Napoleon’s armies, and seized the power. Bolivar traveled to London to seek political support. Although his appeals for help were rejected, he studied the political institutions in London and met with the exiled Miranda, persuading him to lead the movement for independence.

Venezuela declared independence in 1811, but the following year the rebels were defeated by Spanish forces, aided by a terrible earthquake that leveled many of the patriots’ strongholds. For them, it was as if God was on the Spanish side. Bolivar retreated to Nueva Granada and raised a new army. But in 1815 Spanish troops from Europe forced him to flee to Jamaica. There he wrote La Carta de Jamaica (Letter from Jamaica), in which he explained his ideas on Latin American independence. When he returned to South America, he began a 12-year campaign to liberate the continent from the Spanish. In the process, he would earn the title El Libertador (The Liberator). Simon Bolivar liberated Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia and died in Colombia on December 17, 1830.

How Did Latin America Develop?

Although the wars of independence ended Spanish rule in South America, the problems were far from over. New social conditions led to violent conflicts. Power had shifted from the colonial powers to the Creole elites. But for the majority of the population, not much had changed as they were at the bottom of the social structure.

Bolivar, the president of three republics ravaged by the civil strife that followed independence, tried to contain the turmoil with authoritarian constitutions. The Bolivarian constitution of 1826 granted independence to the region but introduced a presidential system for life and gave the president the power to name his successor. The same rigid constitution was adopted in Peru that year. Bolivar’s dream of a united Latin American republic never materialized and in 1829, after years of civil war, Venezuela seceded from Colombia. Bolivar soon realized that Latin America was being divided into a series of separate nations.

Independence was the only good we had achieved at great cost.

Bolivar’s interpretation of the partition process

But trade relations between Latin America and the rest of the world had already begun. Britain sent industrial goods in exchange for coffee, tin, tobacco, and sugar. Trade with other European countries evolved rapidly. The absolutist monarchy over Latin America had ended and Spain’s trade monopoly was abolished. Bolivar was revealed the way forward for the South American continent.

The Timeline of the Latin American Independence

The first victory of the Latin American peoples’ struggle for independence was won in Haiti in 1804 which was a movement spread across the continent in 22 years:

- 1804 – Saint Domingue gained independence from France and became Haiti.

- 1808 – Napoleon invades Spain and deposes King Fernando VII.

- 1813 – Venezuela is liberated by Simon Bolivar, but is retaken by Spanish forces.

- 1816 – The United Provinces of Rio de la Plata (now Argentina) gained independence.

- 1818 – Jose de San Martin wins the Battle of Maipu; Chile is liberated.

- 1821 – Venezuela gains independence at the Battle of Carabobo. Mexico declares its independence.

- 1822 – Antonio Jose de Sucre liberates Quito (now Ecuador) at the Battle of Pichincha. Prince Dom Pedro declared the independence of Brazil.

- 1824 – Antonio Jose de Sucre defeats Spanish forces at the Battle of Ayacucho in Peru.

- 1825 – Sucre liberates Upper Peru and names it Bolivia in honor of the Bolivar.

- 1826 – The last Spanish royalist strongholds in South America fell.

The Slave Who Liberated Haiti: François Toussaint Louverture

In 1804, Haiti became the first country in Latin America to achieve independence. The movement that liberated the country was largely based on the efforts of an African slave named Toussaint Louverture. In 1791, there was a major slave revolt sparked by the French Revolution, and for the next decade, the island was the scene of fierce fighting.

The British, eager to occupy the rich island, supported the plantation owners, but Toussaint’s army forced them to retreat. Toussaint became a governor and tried to restore the damaged economy. In 1802, a French battalion arrived on the island, determined to restore slavery and take control. Governor François Toussaint surrendered and was imprisoned. However, the French army, ravaged by yellow fever, was eventually defeated by rebel forces under Jean Jacques Dessalines. Thus, Dessalines declared Haiti’s independence on January 1, 1804.

Bolivarian Revolution and Simón Bolivar

One of the most incredible achievements of wars of independence in history was Simón Bolívar’s 1819 plan to expel the Spanish authorities from the colony of Nueva Granada (now Colombia). Bolívar envisioned leading more than 2,000 troops across the rain-swamped Venezuelan plateau and up into the Andes Mountains to take the Spanish by surprise at their base in Bogotá.

Bolivar chose the most difficult route and the most dangerous time of the year for the operation he envisioned. He planned to turn both of these factors to his advantage. The rainy season had just begun and the rivers were full. Bolivar rightly thought that the Spaniards would certainly not expect an attack under these conditions.

Confident that his own army of patriots would survive the arduous journey, he set out in late May with 300 infantry and 800 cavalries. The soldiers marched in the pouring rain. Their clothes rotted and tattered on their backs. Each of the streams that flowed weakly in the dry season had turned into rivers that had to be crossed with cowhide rafts. In some places the soldiers waded through waist-high muddy water, even threatened by crocodiles and piranhas.

The food and ammunition they carried with them got soaked and animals began to die. The morale of the soldiers was shaken, but they drew strength from the faith and determination of Bolivar and the generals. Francisco de Paula Santander, the commander of another army of South American patriots, met Bolivar at the foot of the Andes, and on June 12 the two armies were united. But the most difficult part of the journey was yet to come. Bolivar’s soldiers set off for the Pisba Pass with a larger army. A bitter wind blew from the heights and the temperature dropped below zero at night.

Many soldiers died of cold as their clothes were already melted. Some, weak with fatigue, collapsed from exhaustion on the icy paths. The army suffered heavy casualties and only a few horses were left. But beyond the Pisba Pass laid green, fertile valleys where they could find food and new mounts. Moreover, by taking this unexpected route down to Nueva Granada, Bolívar avoided the Spanish outposts ahead.

After sporadic skirmishes, Bolivar found himself facing royal forces led by Jose Barreiro. Under cover of night, however, Bolívar turned back and overran the enemy positions by another route. When Barreiro realized what had happened, he immediately set out for the bridge over the Boyaca River to take up positions and to prevent Bolívar from reaching the capital.

The Republic of Gran Colombia

The two armies faced each other on August 7, 1819. The Royalist vanguard reached the bridge but was repulsed by Bolivar’s troops. Barreiro then took up positions on the north bank. Santander sent his cavalry across a ford below to attack the royalists from the flank. He and Bolivar would offense from the front. The two-pronged attack weakened the king’s army and Bolivar’s cavalry pierced through the center. Barreiro was forced to surrender in less than two hours. This crucial battle opened the road to Bogota for Bolivar and led Nueva Granada to independence. It was a turning point for the northern half of South America and military supremacy shifted from the Spanish to the patriotic Latin forces.

Bolivar now had a large base in Bogotá. In December he became president and military leader of Nueva Granada, with Santander as his deputy. Three days later he announced the creation of a new state, The Gran Republic of Colombia. The republic united Venezuela, Nueva Granada, and the Province of Quito (now Ecuador). Bolivar secured Venezuela’s independence at the Battle of Carabobo in June 1821 and Ecuador gained its freedom in 1822.

Only Peru was still under Spanish rule. It would be Peru, torn apart by racial and power struggles, that would find independence the most difficult to achieve. Chile’s liberator, the Argentine Jose de San Martin, entered the capital Lima in 1821 and declared Chilean independence. But in 1822, after a meeting with Bolívar, he abandoned the war and went into exile.

The Liberation of South America

By 1823, the Spanish had retreated to the south of Peru, while a divided nationalist government controlled the north. This government, weary of civil war and Spanish resistance fronts, asked Bolivar for support. Simon Bolivar arrived in Lima in September 1823; the next few months gave him enough time to assemble a powerful army. In May 1824, he once again began a long march to the Andes.

You are about to complete the greatest task that God has entrusted to man, the task of freeing the whole world from slavery.

Simon Bolivar

The initial royalist forces were defeated at the Battle of Junin on August 6, 1824, but the original royalist army under Spanish Governor La Serna was largely intact. Bolivar returned to Lima to maintain political control and left military matters in the hands of his most capable officer, Antonio Jose de Sucre.

Le Serna advanced and tried to surround the independence fighters. Sucre deftly avoided this trap and the two armies met at the Battle of Ayacucho on December 9, 1824. Sucre won the battle. This heavy defeat ended Spanish rule in Peru and declared Latin American independence to the world. The few remaining royalist insurgents had no hope of reinforcements. In April 1825, Upper Peru was also liberated and renamed Bolivia in honor of Bolivar. By January 1826, all Spanish supporters had been defeated. South America was now fully independent.