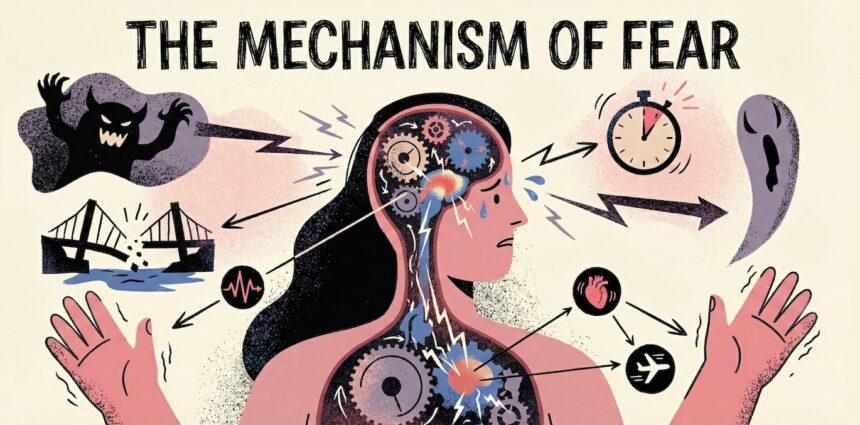

Imagine you see a stray dog running toward you. At that moment, the image of the dog, the sound of its running, and other sensory information is transmitted through the thalamus and cerebral cortex to the amygdala—the brain’s emotional center.

The amygdala is a paired structure deep within the brain, consisting of several nuclei. Two nuclei are responsible for fear: the lateral and central. The lateral nucleus functions as a receiver, taking in information from other structures. The central nucleus acts as a transmitter, sending commands about what to do next.

Your amygdala decides that the running dog is dangerous and sends signals to other brain structures:

- Hypothalamus. It causes the adrenal glands to release the hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline into the bloodstream, preparing your body for fight or flight: you begin to sweat, your pupils dilate, your breathing quickens, blood rushes to your brain and muscles, and digestion slows down.

- Periaqueductal gray matter. This makes you freeze in place, like a deer in headlights. It might seem like a pointless reaction—you’d be better off looking for a rock or stick to fend off the dog. But your brain doesn’t think so. Millions of years of evolution tell it that freezing is an advantageous strategy. The predator might pass by, and you won’t have to waste energy fleeing, risking becoming someone’s lunch.

- Paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. This structure orders the secretion of cortisol—the stress hormone. It conserves energy to help you endure the dangerous situation. Additionally, cortisol allows the amygdala to work at full capacity: since the situation is dangerous, you need to react to any frightening stimuli, and the amygdala excels at this.

Let’s say the dog really was dangerous, barked at you, or bit you. A strong connection between the image of the animal and the pain of the bite has now formed in your amygdala. From now on, the sight of a dog running toward you will trigger fear, even if it’s a friendly neighborhood dog. Moreover, each new episode of fear triggered by a dog will strengthen the neural connections in the amygdala and hippocampus, along with your fear of man’s four-legged friends.

But this doesn’t mean you’ll panic at the sight of a dog for the rest of your life. Thanks to neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to strengthen and weaken connections between neurons—you can overcome your fear.

How to Overcome Fear

Retrain Your Brain Through Action

As mentioned above, the central nucleus of the amygdala actively participates in creating fear: it connects safe stimuli with presumably dangerous ones and sends signals to other brain structures. Because of this nucleus’s work, your neighbor’s dog, which has never bitten you, makes your heart beat faster and your palms sweat.

In his book Taming the Amygdala, John Arden explains that the central nucleus can be overcome by another part of the amygdala—the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. To activate it, you need to take concrete action, such as petting your neighbor’s dog.

Furthermore, action activates the prefrontal cortex. Then the following happens: signals continue to arrive at the lateral nucleus of the amygdala, but the active prefrontal cortex suppresses the connection between the lateral and central nuclei. As a result, no commands come from the central nucleus—fear doesn’t arise.

If you want to get rid of fear, confront it head-on.

Want to overcome your fear of dogs? Get your own or play with a friend’s dog. The prefrontal cortex will assess the situation and prevent the amygdala from expressing fear. Eventually, the image of a dog will lose its “danger” label, and you’ll stop trembling at the sight of one.

How long you’ll need to play with someone else’s dog and whether the fear will return if you suddenly see a stray dog depends on how long you’ve been afraid.

Do It Quickly

The sooner you take a step toward your fears, the better. Each episode of fear strengthens neural connections in the amygdala, making it increasingly difficult to overcome.

The ideal time to fight fear is the first week after it forms. Scientists at McGill University discovered that fear extinction is related to CP-AMPAR receptors in the neurons of the lateral amygdala.

In the first 24 hours after a new fear forms, the number of these receptors increases, then returns to normal levels within a week. After that, the fear becomes firmly established and becomes harder to fight.

In experiments with mice, scientists identified the ideal scheme for fighting fear: within the first 24 hours after its formation, you need to see the frightening stimulus again, then work on unlearning the fear. For example, first you watch a video of an angry dog, then half an hour later you pet a friendly neighborhood dog.

The video activates the fear and ensures neuronal plasticity, while playing with the dog helps eliminate the fear. However, this scheme only works in the first week, while the CP-AMPAR receptors haven’t returned to their previous levels. If you miss the window for working with the fear, it will be much harder to completely overcome it.

To prevent fear from becoming entrenched, try to overcome it as quickly as possible.

Activate the Prefrontal Cortex

Since the prefrontal cortex can suppress excessive amygdala activity, activating it helps fight fear and anxiety.

There are two proven ways to “turn on” this brain region:

- Exercise. Physical activity increases prefrontal cortex activity.

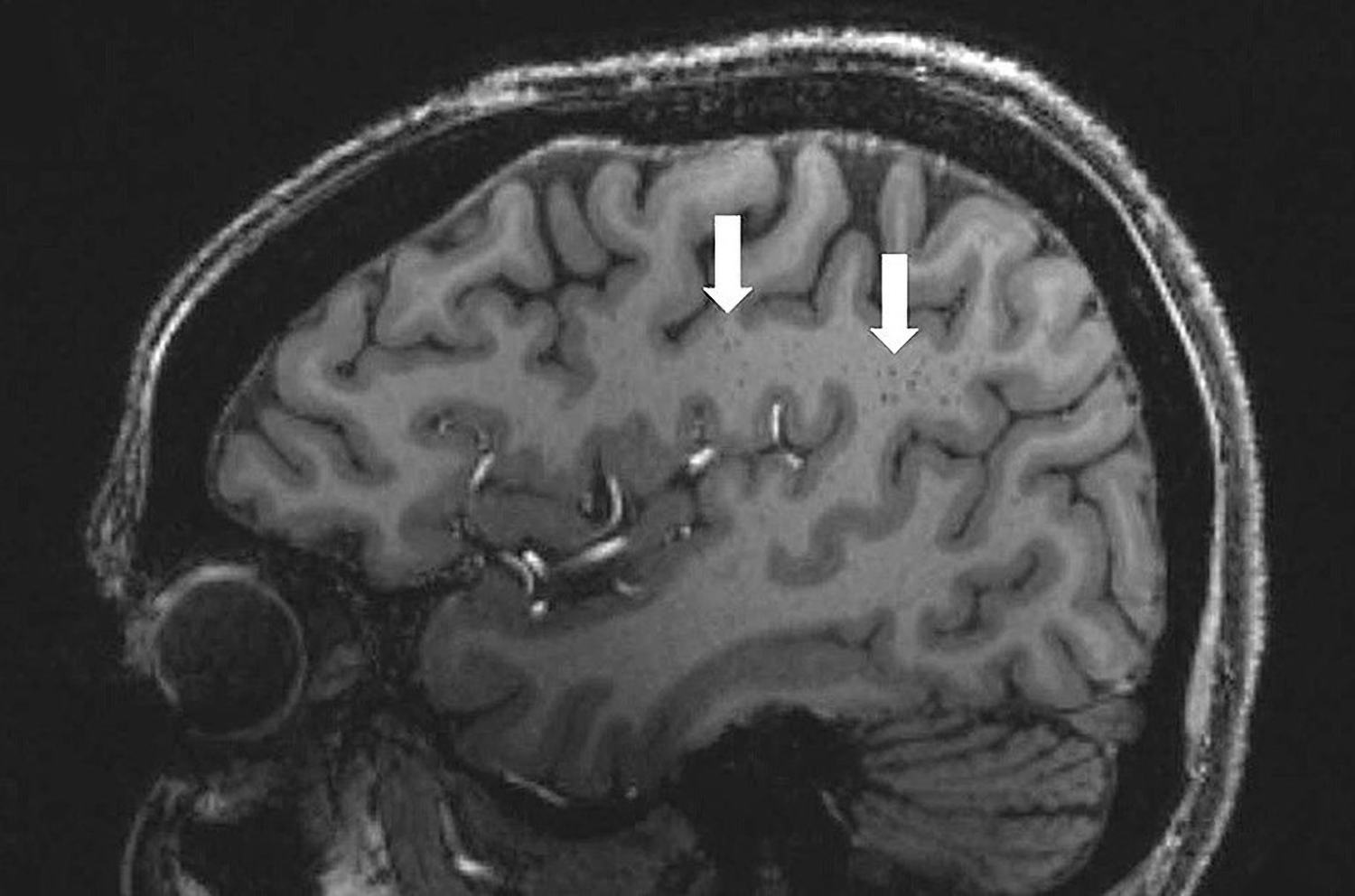

- Meditate. Meditation increases gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and decreases it in the amygdala. That’s why Buddhist monks are so calm: after many years of practice, their amygdala has shrunk and stopped being frightened by everything. However, a single meditation session won’t help: you’ll need to meditate for at least eight weeks, 40 minutes a day, for structural brain changes to occur.

Remember: meditation and exercise will help you fight anxiety, but won’t rid you of already-formed fears. You can only do this by deliberately placing yourself in a similar stressful situation that ends favorably.