The Roaring Twenties (Années folles) in France refer to the period between the 1920s and 1929, a decade marked by a spectacular economic recovery and significant cultural and intellectual fervor. Benefiting from international détente, French industry established itself on European markets, and living standards improved. Paris became a vibrant hub of literary and artistic creation. Traumatized by the painful experience of World War I, French society underwent a transformation, while a minority gave rise to the “Roaring Twenties,” a period emblematic of the desire to forget the war and seek entertainment.

France at the Dawn of the Roaring Twenties

On July 14, 1919, all of France celebrated victory, but at what cost? Although France was among the victorious powers of the war, the victory was Pyrrhic, and the nation now had to reckon with its losses. As early as December 1918, the Under-Secretary of State for War estimated the number of French combat deaths at 1,385,000. Out of the 8,660,000 men mobilized to fight under the French flag, more than 7 million survived. Yet, many died in the immediate aftermath of the war due to bronchitis, poorly treated wounds, and other causes. Others were war invalids, a constant reminder that victory came at a price. In fact, it is estimated that there were 25,000 amputees and 14,000 men with severe facial injuries, known as “gueules cassées.”

Demographically, France faced a problem it had not encountered in 1944. Unlike the post-World War II period, the aftermath of the First World War did not see a baby boom, destabilizing French demographics, which were already less dynamic than those of several other countries at the end of the 19th century.

The birth deficit caused by the war is estimated at 1,400,000. This human loss (the “hollow classes”) altered the age pyramid and led to an overall aging of the population. By the early 1920s, the proportion of people over sixty already exceeded 13.5%, one of the highest percentages in Europe.

Songwriters quipped, “Why do we have sixty-year-old politicians? Because the seventy-year-olds are dead!”

Legislatively, a law was passed on July 31, 1920, criminalizing abortion. Additionally, massive immigration was encouraged. In the 1920s, over a million immigrants came to France. While immigrants represented 2.7% of the population in 1911, they accounted for 6.96% by 1931. By then, France had become, “relative to its population, the world’s leading immigration country, ahead of the United States” (Ralph Schor).

Among this new wave of life-saving immigration, Poles were the most numerous, followed by groups from Mediterranean countries (Portugal, Italy). As a result, some northern cities (Paris, the north, and east of France were the regions with the highest immigrant populations) were almost entirely inhabited by Poles, such as the town of Ostricourt.

To this grim human toll was added a tragic material cost. The war affected ten French departments in the north and east, where the most significant damage occurred. Some cities were completely devastated, like Saint-Quentin. Architectural damage was extensive, symbolized by the destruction of Rouen Cathedral. Additionally, 450,000 houses were partially or completely destroyed, and 5,000 km of railways were rendered unusable. There is no doubt that France paid a heavy price for this war, which many hoped would be the “war to end all wars,” a price that also brought political changes.

From the National Bloc to the National Union

“Few periods in our history have retained such a negative image” (Jean-Jacques Becker and Serge Berstein) as the National Bloc. An alliance of the center and the right, the National Bloc came to power on November 16, 1919, following the legislative elections, the first since the war. A majority of the deputies were veterans, earning the Chamber the nickname “Chambre bleu horizon,” in reference to the color of French soldiers’ uniforms. Although Clemenceau might have hoped to become president, he was denied the position due to his anticlericalism and authoritarianism.

With the election of Paul Deschanel as President of the Republic in January 1920, France returned to a tradition that valued presidential discretion. The National Bloc governments prioritized foreign affairs, specifically securing peace, even though the war had ended. Since the Versailles Conference concluded on June 28, 1919, the focus was on finding solutions to prevent another war.

A peace-oriented organization, the League of Nations (LN), was established, though it showed its limitations by lacking an armed force. The LN was essentially formal, and some leaders could easily ignore formal condemnations unaccompanied by military threats. Nevertheless, the LN provided reassurance, which was crucial in the 1920s.

France, following the words of Finance Minister Lucien Klotz, hoped that “Germany will pay.” More than hope, France demanded it. Various commissions and plans aimed to determine the amount of war reparations owed by Germany. When Germany showed reluctance to pay, France decided to invade the Ruhr in 1923, an industrial region that would allow it to exploit coal resources.

However, France soon had to retreat under international pressure. Moreover, it was the international powers, primarily England and the United States, that blocked French demands, fearing the spread of revolution (which had already affected Germany and Russia after the war) in Germany. British and American leaders refused to see Germany on its knees, as France desired, because a financially and morally broken country would be more inclined to embrace revolutionary ideas. In short, reparations were consistently reduced, influenced by the work of several economists, most notably John Maynard Keynes (The Economic Consequences of the Peace).

Domestically, the left was shaken by a division that erupted during the congress held in Tours from December 25 to 30, 1920, which aimed to determine whether the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) would join the Third International.

To do so, it had to accept 21 conditions. A majority of members (Marcel Cachin, Ludovic Oscar Frossard) accepted, while a minority (Paul Faure, Léon Blum, who preferred to “keep the old house”) refused. As a result, the French Section of the Communist International—the precursor to the French Communist Party (PCF)—was formed, comprising those who aligned with Moscow. Thus, the French left appeared divided. Similarly, the labor movement saw a split with the creation of the CGT-U (Unified General Confederation of Labor) in 1921.

The Left-Wing Cartel

In the 1924 legislative elections, the Left-Wing Cartel emerged victorious, an alliance of radicals and socialists, marking the end of the National Bloc. President of the Republic Alexandre Millerand resigned, and the Cartel proposed Paul Painlevé as his successor. However, it was the Senate President Gaston Doumergue who was ultimately chosen, sparking frustration within the Cartel, which had to accept the outcome. The Cartel’s policies were characterized by anti-clericalism (France closed its embassy in Rome) and efforts to replenish state finances. Indeed, France was struggling financially, with a significant deficit. This was the main challenge faced by Édouard Herriot, the Prime Minister, who, despite attempts to reduce the deficit, failed to do so. On July 21, 1926, the “Cartel experiment” came to an end.

The financiers and the Bank of France had prevailed over the Cartel. Raymond Poincaré, the architect of the Sacred Union of 1914 and former President of the Republic (elected in 1913), became the Cartel’s immediate successor. The period of the National Union, with Poincaré at the helm, appeared as a high point, contrasting sharply with the eras of the National Bloc and the Cartel. France regained confidence, the economy improved, and society began to embrace other cultures, gradually forgetting the war.

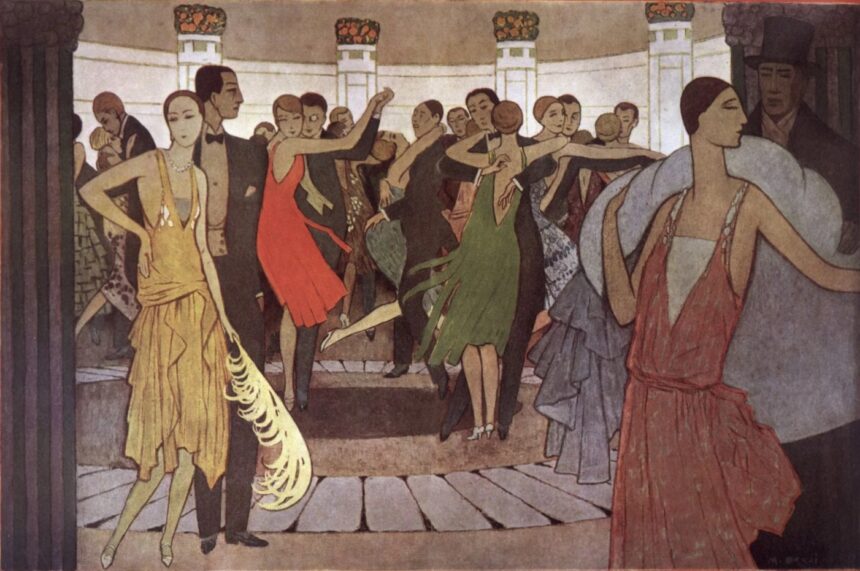

The Roaring Twenties: The Age of the Avant-Garde

Demographically weakened, French society underwent significant transformations. Rural society gradually lost ground to urban society. By 1931, for the first time in its history, France had more urban dwellers than rural inhabitants (though the definition of a “city” remained debatable—was the threshold of 2,000 inhabitants appropriate? What did it signify?). The beginnings of a mass culture began to emerge, foreshadowing the 1930s. The Roaring Twenties reflected a social decompression after the hardships of the war and the reconstruction period.

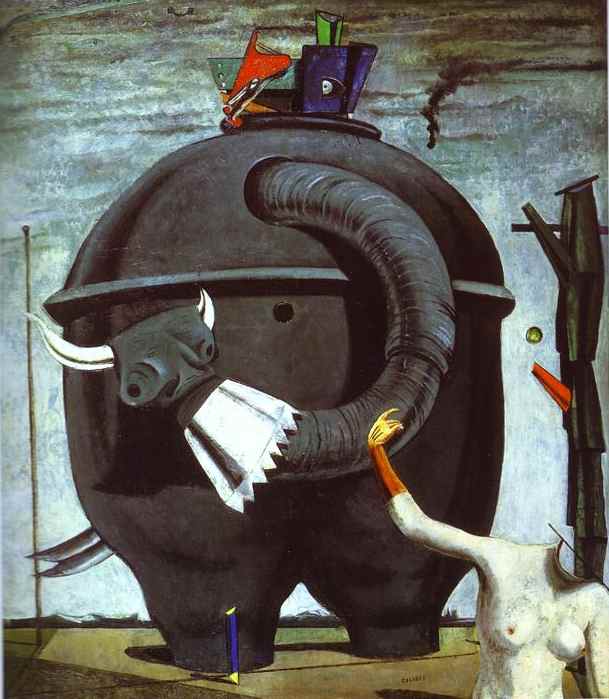

Cultural, artistic, and religious life flourished. Paris in the 1920s became the epicenter of Surrealism. Figures like André Breton, Philippe Soupault, Robert Desnos, and Paul Éluard, influenced by Freudianism, gave free rein to the expression of their unconscious. They practiced automatic writing, explored hypnosis, created perplexing objects, and in 1926 launched the game of the “exquisite corpse,” where participants randomly wrote words on small pieces of paper to form sentences.

Musical aesthetics were revitalized by Erik Satie, a witty and ironic figure close to the Surrealists, who became the “mascot” of Les Six (a group including Darius Milhaud, Arthur Honegger, Francis Poulenc, Georges Auric, Louis Durey, and Germaine Taillefer). Under the patronage of Jean Cocteau, these composers, though of very different temperaments, sought to react against musical Impressionism and the influence of Debussy (who died in 1918). They embraced polytonality and polyrhythm. Satie, a cabaret pianist who died in poverty in 1925, loved rhythmic audacities and pranks, giving his compositions humorous titles (True Flabby Preludes for a Dog; Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear) and inserting unexpected notes to startle or amuse listeners. Maurice Ravel composed his famous Boléro in 1928, while Vincent d’Indy perpetuated the ideas of César Franck and taught composition until his death in 1931.

The Nouvelle Revue Française, centered around André Gide, thrived, while war literature (by authors like Roland Dorgelès, Henri Barbusse, and Joseph Kessel with L’Équipage) enjoyed great success. By the end of the decade, cinema saw the emergence of sound films, though France lagged a few years behind the United States. The French film industry faced challenges, less prosperous than during the Belle Époque, when it had dominated global markets.

A New Way of Life in France

Now, France faced increasingly strong competition from Hollywood, which had capitalized on World War I and benefited from a wave of Americanophilia that swept postwar France. The rise of music hall with stars like Joséphine Baker (marking the decline of the café-concert, emblematic of the Belle Époque), the adoption of American dances like the shimmy and especially the Charleston in the mid-1920s, and the growing enthusiasm for jazz and swing with artists like Louis Armstrong and Benny Goodman all reflected this trend. Musical stars such as Mistinguett (who performed at the Moulin Rouge), Fréhel, and Maurice Chevalier became increasingly popular, especially as radio ownership grew, reaching 500,000 receivers in France by 1925 (600,000 just two years later).

In the world of fashion, Coco Chanel emerged as an icon, while the Art Deco style dominated architecture and design. In print media, Le Petit Parisien, already the leading daily in 1914, continued to grow, with a daily circulation exceeding 1.5 million copies. The press diversified further, with the creation of sports, music, and other specialized newspapers.

Although the 1920s are often called the “Roaring Twenties,” it is clear that society was changing. However, the garçonne (flapper) remained a myth, and women were still largely expected to stay at home (in line with the pro-natalist policies of the early 1920s, which emphasized that a woman’s duty was to bear children for France). In this regard, the postwar period did little to change the status of women in France, and World War I did not emancipate them. Proof of this is that while women made up 37.7% of the active population in 1911, this figure had dropped to 35.5% by 1931.

The End of the Roaring Twenties

In reality, except in the cultural domain, where the era was exceptionally rich, the Roaring Twenties did not profoundly change French society, which remained rigid in its social structures (for example, women’s employment did not survive demobilization), still rooted in rural traditions and a culture of saving. Victorious in the Great War, France was haunted by the fear of another conflict and retreated into a visceral pacifism, which would weaken it in the face of rising totalitarian ideologies, particularly Nazism.

The 1929 crisis brought a brutal end to this second “Belle Époque.”