Submarine fiber optic cables provide the backbone for almost all international data transmissions. They are crucial to the functioning of the Internet and, by extension, the economy and daily life in many areas of the world. If this infrastructure is so important, how safe is it? How vulnerable are the underwater cables and global Internet connection exactly?

- Understanding the significance of the global network of underwater cables

- The causes of cable breaks and the consequences

- How can you cut off an underwater communication line?

- The consequences of attacking the undersea cables and the greatest threats

- There are dangers even without explosive devices and divers

As many people learned in September 2022, during the explosion of the Baltic Sea pipelines, a significant portion of the vital underwater cables submerged in water were not sufficiently safeguarded. The weak point for Europe and other areas is not the pipelines themselves, but rather the many fiber optic connections that support global data traffic.

Understanding the significance of the global network of underwater cables

Veins of international communication

Whether we’re chatting online, having a video conference, or watching a movie online through a streaming service: All this online activity data has come a long way to get to us, and much of it has been submerged along the way. This is because submerged cables carry 98% of all Internet traffic today. In fact, the backbone of the Internet is a network of fiber-optic cables that run under the ocean, connecting each continent to the others.

Submarine cables are able to handle this by transmitting data at up to 200 Tbps with a latency of less than 60 ms. This is an order of magnitude higher than what can be achieved using traditional geostationary satellite connections. Orbital data transfer will only become relevant when low-Earth orbit satellite networks are fully operational. This is due to the fact that latency guarantees of 30 ms or fewer are anticipated from Starlink and the company. Their transmission speeds of 100–500 Mbps are far lower than those of undersea cables.

Interconnected web

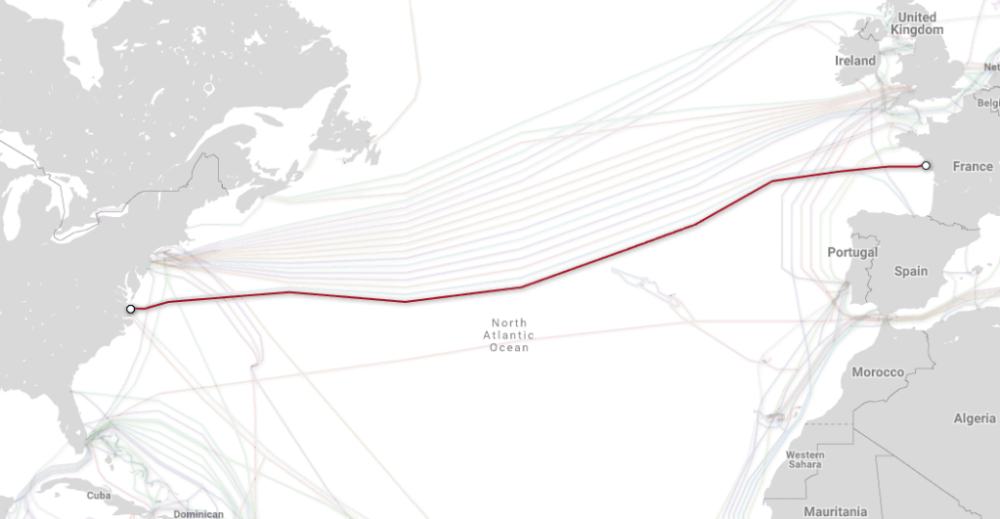

The combined length of all undersea cables in the world is 1,300,000,000 kilometers. The more than 475 strands of metal run parallel to the shores of the continents, dive under the waters, and weave together the Southeast Asian island nations into a single, cohesive whole. More than 20 of these cables link Europe and the East Coast of the United States; a comparable number connect the West Coast of the United States to Asia.

SeaMeWe-3, the world’s longest undersea cable, spans an impressive 24,200 miles (39,000 kilometers). It begins on the western coast of Europe and continues over the Mediterranean and Red Seas to the far eastern coasts of Asia and Australia. The 2Africa cable will be much longer, wrapping twice around the African continent when it goes live in 2023. While transatlantic cables typically terminate at a single site on each end, coastal and transoceanic cables may terminate at various stations in different nations due to their extensive branching.

The data finds its own way

Neither the cable companies nor the data senders can control which cable a data packet uses as it zips across the world’s vast underwater cable network. The internet is a maze through which digital data wanders aimlessly. A standard protocol for data packets is to use the quickest path. An e-mail traveling from New York to Madrid may sometimes bypass the transatlantic cables in favor of a faster delivery through the Pacific and Asia when bandwidth constraints make the direct route too sluggish.

The volume of data traveling via these seabed arteries is always growing. Every day, more than 10 trillion US dollars worth of financial transactions go via the network of underwater cables. Since practically everything now exists in the cloud and the economy is becoming more digital, businesses cannot function without constant access to the Internet. Furthermore, the data traffic we create through our individual use of social media, streaming services, and Internet-based television shows extends far beyond the borders of continents.

Glass-cored “garden hoses”

Most undersea cables are hardly thicker than a garden hose, despite their critical role. They typically have a diameter of only a few centimeters. The innermost layer of such a hose consists of gel-coated glass fibers. Submarine cables have protective sheaths around them, and many bundles of cables, each with its own sheath, are often included inside a single cable. This offers some redundancy, since data flow may still proceed in the other bundles if just a portion of the undersea cable is damaged.

Submarine cables not only comprise fiber optic bundles, but also copper lines, which are utilized to provide power to the signal amplifiers and other components. A steel fiber structure, either inside the cable’s core or as a sheath surrounding this inner layer, is there to keep the fragile glass fibers from bending the cable. A layer of shock-absorbing insulation and an outer layer of protection from the ocean surround the whole assembly.

Before the landing points and in shallower water, the “hoses” are only about the thickness of an arm, but thereafter they are as thin as a pencil. This will help prevent the cables from being harmed by things like animals, ship anchors, and bottom trawls. While much of the world’s submarine cable system is buried near shore, the vast majority of it is simply laid bare on the ocean floor in the deep sea.

Submarine cables, despite appearances, are quite sturdy: They have a mean lifespan of 25 years, and failures owing to fatigued materials or faulty repeaters and control units are exceedingly unusual occurrences. Meanwhile, damage from outside sources occurs often…

The causes of cable breaks and the consequences

Cut and pulverized

In January 2022, a submerged volcano off the coast of Tonga erupted, causing extensive shock waves and blanketing the island country in ash. The solitary underwater cable that connected Tonga to the rest of the world was also severed by the earthquake the eruption created. This resulted in a five-week period during which most islanders had no access to the web.

Ship anchors, trawls and natural disasters

Despite all the ethereal-sounding euphemisms like cloud or cyberspace, the Internet is built on physical hardware—and that hardware, including underwater cables, can be destroyed. Each year, the worldwide subsea network suffers roughly a hundred accidents, most of them small, including damage to fiber optic cables. Most cable failures may be traced to a breach in the cable’s outer sheath, which allows salt water to enter the cable or causes the optical fibers or bundles to break. In such a scenario, transmission speeds are slowed down, but the link is not severed entirely.

Accidental damage along the shore caused by ship anchors, dredging, or trawl nets dragged over the seabed is the most typical source of such disturbances and failures. About 70% of cable failures and breakage may be attributed to them. In 2008, for example, a ship moored off the Egyptian coast, disrupting the FLAG Europe-Asia and SeaMeWe-4 cables that connect Europe and Asia across the Red Sea. Due to this, over 75 million individuals in Asia and the Middle East were left with severely restricted Internet access.

Approximately 20% of all cable damage is the result of natural events like earthquakes, undersea landslides, or volcanoes. However, this kind of damage is often significantly more severe. Commonly, they will attack and destroy many submarine cables all at once. In December 2006, for instance, an earthquake off the southern coast of Taiwan knocked off many major links in Asia, leading to days of downtime for Internet users in Hong Kong, China, and other Asian nations.

How vulnerable is Europe?

Therefore, the severity of the effects of a broken undersea cable is proportional to the degree of redundancy included in the system. But the likelihood that data will continue to flow unimpeded increases as the number of alternative land and submarine cables available to compensate for the loss of bandwidth caused by an interrupted connection increases.

250 lines, of which two-thirds are undersea cables, link Europe to the United States and the rest of the globe, making it one of the major nodes in the global communications network. France and Italy are major hubs for data transit between the Mediterranean and Asia. In the European Union, the majority of cables crossing the Atlantic Ocean land in the United Kingdom, with just a few dozen crossing the English Channel to reach the continent.

However, this has been shifting after Brexit. New high-capacity cables arriving on the coastlines of France and Denmark, as well as in Bilbao, Spain, demonstrate this change. EU officials want to lessen their reliance on the United Kingdom, and they also believe that spreading the landing spots out throughout the continent will make it more difficult to pull off a hoax.

Nonetheless, changes have been occurring even since Brexit: The arrival of new high-power cables on the French and Danish beaches and in Bilbao, Spain, demonstrate this transition. The European Union (EU) would want to lessen its reliance on the United Kingdom (UK), and dispersing the landing sites across many regions lowers the probability of a global outage.

Bottleneck on the Red Sea

The same holds true for where the cables themselves are situated in the ocean. Although transatlantic cables may be laid out more widely over Europe’s lengthy western coast, the same cannot be said for Asian and African links. This route between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean through the Red Sea is the largest bottleneck in the EU. This corridor provides the backbone of Asia’s connectivity.

This chokepoint was directly affected by the unintentional capping of cables in 2008, albeit only two of the several intercontinental cables passing through this area were really cut. Since 16 of the EU’s most vital cables in the Suez Canal region had to be relocated to the beach after being damaged by passing ships, the area is now safer. However, there is an additional danger here since Egypt is home to intercontinental cables. Because of this, it is vital for the EU to maintain strong ties with Egypt to secure digital connections.

Is there any danger that the underwater cables would be purposely damaged or disrupted?

How can you cut off an underwater communication line?

Attacking the system

How susceptible are our digital communications backbones to politically or terroristically motivated acts? Few individuals, including those in positions of authority, realized until recently how much of our vital infrastructure is hidden under the waves. This reality entered the public and political knowledge only after September 2022, when the Nord Stream gas pipelines were sabotaged in the Baltic Sea.

In part, this is because no one ever sees it. Water blindness refers to the widespread propensity to ignore events occurring at sea. In deep water, their location is only shown approximatively on nautical maps. As a result, they are harder to target.

However, this is not the case along the coast: Here, the nautical charts accurately depict the path of the cables to protect mariners from potential dangers such as anchorages and trawl nets. Since the water is rather shallow, a reckless attack might be planned and carried out with relative ease.

On the other hand, deep-sea cable damage takes far longer to repair than nearshore damage because of the complexity of the repair process. The broken sections of cable need to be brought to the surface by a diving robot once the precise location of the damage has been determined. In such a circumstance, reconnecting the broken glass fibers one at a time may take weeks.

Tearing, blasting or cutting

So, what are the ways in which an undersea cable can be damaged? The simplest method, the paper claims, involves neither advanced knowledge nor expensive equipment. The experts concluded that any civilian ship, including fishing vessels, freighters, pleasure yachts, or research vessels, might be used as a weapon by cutting the cable using improvised methods, such as the anchor or towing equipment.

Mines or other remotely detonated devices would be a second option. The latter is simple and inexpensive to create. Furthermore, the glass fibers are so fragile that they can be broken with a very small amount of explosive force. Remotely operated or manned submersibles or drones are a third potential sabotage method. Increasingly widespread in the diving business, criminal groups have built and deployed such submersible devices for smuggling activities. This technology might be used to place explosives or sever the cable.

The military and other groups with access to specialized expertise and high-tech equipment are not alone in their willingness to target underwater data cables. Attacks against cable infrastructure might be low-cost operations that do not necessarily require high-end skills.

Landing stations as a neuralgic point

This is all the more true when attacking not the submarine cables themselves, but their landing points. These facilities, located at the ends of the submarine cables, are important switching points where data traffic arriving through the submarine line is transferred to one or more land-based backbone lines. While these land-based stations are protected by fencing and security, they are still significantly more vulnerable than the submarine lines.

In 2017, a report by the British think tank Policy Exchange also highlighted this risk. The cable landing points “often have minimal protection, making them vulnerable to terrorism,” warned Rishi Sunak, a member of parliament and author of the report. Attack scenarios range from simply cutting power to detonating improvised bombs to a missile attack. In addition, some landing points no longer have human crews, but only run remotely.

Despite these scenarios and risks, to date, there has been no known targeted attack or act of sabotage by political or criminal actors on a submarine cable. However, this does not mean that this will remain the case…

The consequences of attacking the undersea cables and the greatest threats

What would be the impact if someone destroyed one or more of those undersea Internet cables? And who would be the possible perpetrators of such attacks on critical infrastructure? Aren’t they automatically cutting their own flesh as well?

Cable cutting with only limited effects

Unlike many other regions, the failure of just one submarine cable would have little impact on the continents, including North America or Europe. Given the large number of cables and the high level of redundancy, an EU-wide Internet blackout would be highly unlikely. As long as there are still sufficiently fast alternative routes for the data, this would probably be barely noticeable to users.

However, a coordinated attack on multiple cables could cause significant disruptions. That’s because alternate routes would then become scarce and the available bandwidth for intercontinental data transmissions would drop. Such a scenario would be conceivable, for example, if a landing point were destroyed at which several submarine cables terminated at the same time. This is particularly the case with stations in the United Kingdom, where several transatlantic cables come in at the same time. But an attack on the bottlenecks in the Red Sea or the Strait of Gibraltar also has the potential to cut several cable connections at once.

Nothing would work without the transatlantic cables

The impact on Europe would be particularly severe if the transatlantic connections were to be interrupted. Although this is an almost impossible scenario due to the large number of submarine cables, it would be devastating. If Europe lost the cable lines to the U.S. tomorrow, the Internet there would simply collapse.

Because about 80 percent of the content European users consume comes from the US. Almost all programs, platforms, and websites of the major U.S. tech companies in Europe also need a connection to the U.S., despite regional data centers in Europe.

However, experts believe that a targeted attack on the submarine cables that connect key EU military outposts to mainland Europe is much more likely. Accordingly, attacks on submarine cables could be carried out to affect naval bases in Djibouti (East Africa) or Bahrain (Middle East), which are critical to current naval operations in the Middle East, such as in the Strait of Hormuz. But other submarine cables used primarily by the military could also be targets.

It would be similarly problematic if the repair infrastructure were attacked in addition to the cables. That’s because there are only four ships stationed in Europe designed to repair submarine cables—two for the Mediterranean and two for the Atlantic. If they fail, it could take days to weeks to repair the cable damage.

Submarine cables outside the shallow water zones are exposed on the seafloor and at risk of being destroyed by anchors and trawl nets.

The Russian threat?

But who could benefit from such an attack on critical communications infrastructure? Actors from hostile or rival countries are considered the greatest danger. For some time now, Russia has been at the top of the list as a potential attacker, and not just since the start of the Ukraine war in February 2022. As early as 2015 and 2017, the presence of the Russian ship Yantar off the U.S. coast caused tensions, as this vessel has two mini-submarines and thus the ability to detect and attack submarine cables.

NATO Admiral Andrew Lennon said in 2017 that “We are now seeing Russian underwater activity in the vicinity of underwater cables that I don’t believe we have ever seen.” Russia’s interest in the seabed infrastructure of NATO countries has obviously intensified. Submarine cables in the European seas have seen an uptick in sightings of Russian ships in recent years. Off the coast of Ireland in 2021, a Yantar mini-submarine performed a deep-dive test, which just so happened to be along the route of the AEConnect-1 and Nordic transatlantic cables. Russia once again conducted naval drills in this region in 2022.

Russia has both the expertise and motivation to utilize unconventional and hybrid warfare techniques, including disruption of communications networks. During the 2014 takeover of Crimea, Russia severed the peninsula’s primary cable link to the rest of the world in an attempt to censor the news and other information.

China, too?

Submarine cable assaults are very worrying, but Russia isn’t the only possible culprit. Western economic rivals, most notably China, may gain an advantage if they disrupt digital infrastructure. In particular, China is far less reliant on the international Internet than either Europe or the United States. For political reasons, the government has cut off access to numerous digital services and platforms from the global Internet, despite recent investments in its own infrastructure.

If China were to lose all the deep-sea cable links linking it to the globe tomorrow morning, simply nothing would happen in China. It’s possible that Shanghai-based stock traders may suffer a cardiac arrest if they are suddenly cut off from the London Stock Exchange. On the other hand, for the Chinese people, absolutely nothing would change.

Nonetheless, analysts agree that China’s danger to underwater cables and digital infrastructure is more cyber than physical.

There are dangers even without explosive devices and divers

Manipulation and espionage

To disrupt, manipulate, or spy on the data flow of an area or nation, there are far more subtle, digital means that don’t need explosive devices or sabotage. Data rerouting, software backdoor eavesdropping, and even digitally blocking an undersea connection are all examples.

One possibility is to interfere with data transmissions over the internet. Digital data has a mind of its own. Therefore, its path cannot be controlled directly, but it is open to indirect manipulation. If you redirect the most direct route via your own territory, you can guarantee that the data you want enters the network. Most of the time, the corporations whose interests the cables serve also have to be considered throughout the route design process. This is because most underwater cables are jointly controlled by a group of different telecommunications corporations, rather than any one country.

Cable investors may affect the flow of global Internet traffic by picking the capacity and connectivity nodes of new underwater cables. Data follows multiple channels and crosses international boundaries as the Internet’s physical structure evolves. As a result, the nations will be able to monitor and maybe intercept each other’s communications.

U.S. tech giants like Google and Facebook, as well as a Hong Kong firm, explored the possibility of laying an underwater cable connecting the two cities in 2013. As of June 2020, the U.S. Communications Administration has decided against green-lighting the endeavor. According to the U.S. government, this latest technology cable, when finished, would be by far the quickest fiber-optic link in the U.S. to the whole Asian metropolitan region. Thus, data that might include sensitive information would likewise be sent to China through this line.

Access through operators and publishing companies

The second example shows how to get at this information. Submarine cable operators and publishers both have the technical ability to manipulate and intercept data digitally. Experts, notably in the United States, are concerned about China’s growing involvement in the submarine cable industry. In the year 2021, Chinese state-controlled firms were operating 44 different underwater cable systems.

Many of these cables do not even have a landing site in China, much less pass into Chinese waters. However, operators may intercept data and even block the flow of data entirely using the control software and other components. Because they provide the gear and software to run the cables and repeater stations, the businesses that lay and maintain the cables on behalf of the operators may, in theory, also insert backdoors into the components that are subsequently utilized by state actors.

Here, Westerners’ attention has been focused on Huawei Marine, a Chinese firm that lays and repairs a lot of underwater cables all over the globe. The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) estimates that the corporation has installed or maintained 25 percent of the world’s cables. Since Huawei Marine was slated to handle the design and laying of a cable project in the South Pacific, Australia abruptly canceled the project out of safety concerns.

Brand-new players like Google, Amazon, and more

Submarine cables allow not just nation-states but also private corporations to exert control over international data transmissions. Nearly two-thirds of all submarine fiber optic cables are now controlled by private consortiums, and major IT firms are progressively investing in their own cables. For instance, Google manages or cooperates with ten underwater cables, Amazon owns two, and Microsoft and Facebook are responsible for the two major new transatlantic connections.

All four IT giants are expanding their spending on cable infrastructure, which helps move data over oceans and continents and into their own cloud networks. But, it also creates a new dependence. Of course, they won’t be content with just offering this infrastructure, but then want to use it to sell their services along with it, and they can also control to some extent how far and how well other companies can gain access to this network.

What are the options here?

This is compounded by the fact that there are almost no worldwide legal standards governing the installation and maintenance of underwater cables. A majority of the requirements are related to technological norms. Thus, the market and the interests of investors and operators are major factors in deciding who lays a cable where. Cables running across territorial seas and land stations located inside a state’s borders are subject to the approval of that state’s government. However, unless they are the customers and the operators of the cables, their sway is restricted beyond that.

Submarine cables play a major role in corporate control over the development, operation, and safety of the Internet worldwide. This is a cause for worry given the meteoric rise of cloud computing, especially in mission-critical areas like the military, the financial industry, logistics, and healthcare. Submarine cables are the backbone of the Internet. Therefore, it is more crucial than ever to fortify the safety and durability of this essential infrastructure.

Given this, European and American operators and governments should pay even more attention to underwater cables, their operators, and the potential risks to this infrastructure than they have in the past. Physical sabotage could be stopped by keeping a closer eye on potentially dangerous behavior at sea, making shore stations more secure, and paying more attention to who owns the underwater cables that connect us to the internet.