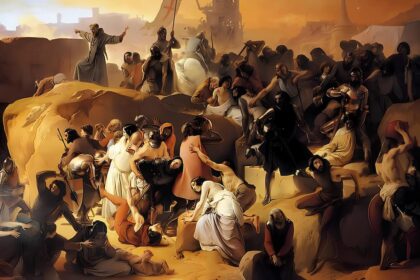

It has been almost a century since Urban II launched the Crusade to liberate Jerusalem, when the city was reconquered by Saladin in 1187. The Latin states were weakened, the county of Edessa had even been destroyed, and a previous crusade, led by two major Western sovereigns, had miserably failed. The situation was thus critical when a new crusade was proclaimed by Pope Gregory VIII; thus began the Third Crusade, perhaps the most famous, as it pitted great Western kings, including Richard the Lionheart, against the already legendary Saladin.

Why is the Third Crusade sometimes called the “Kings’ Crusade”?

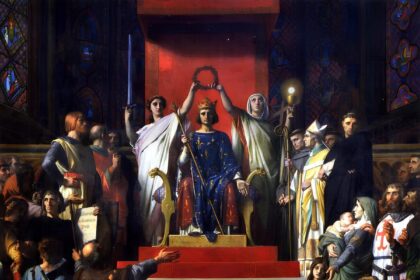

The Third Crusade is often referred to as the “Kings’ Crusade” because it was led by three of the most powerful European monarchs of the time: Richard I of England, Philip II of France, and Frederick I Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire. Their involvement highlighted the importance and scale of this crusade compared to previous ones.

The Crusade for Peace in the West?

The situation was actually much more complex, and the papal decision to call for a crusade was probably not solely due to the fall of Jerusalem and the main Latin strongholds in the Holy Land. Indeed, the West was embroiled in a war between the Capetians and the Plantagenets! For the former, Philip II of France (Philip Augustus) had consolidated his power in the Kingdom of France and could now turn against the already hereditary enemy, who held significant possessions on the continent, such as Anjou and Normandy.

The Plantagenets, led by Henry II, were experiencing serious problems with his sons, particularly Richard and John. The King of France did not hesitate to support them during the years 1186–88, and a weakened Henry II had to give in, despite a temporary reconciliation with Richard.

The latter succeeded him upon his death in 1189.

As early as 1187, however, Henry II had promised to respond to the call for a crusade from Gregory VIII (renewed by his successor Clement III); Richard was to take up the mantle. This did not bother him at all, as he was not very interested in the Kingdom of England and instead wanted to make a name for himself through his military exploits; he too had promised to take up the Cross at the end of 1187. This did not prevent him from persuading Philip II of France to accompany him, probably to avoid his French rival attacking him from behind once he had left for the Holy Land. Louis VII’s son could hardly refuse to undertake this pilgrimage.

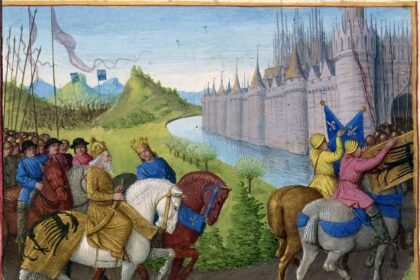

The two sovereigns prepared to depart around 1190. In England, Richard managed to impose the “Saladin tithe” to fund his crusade, but Philip II of France had to do without it, which would later cause considerable problems for royal finances. The two kings met in early 1190 to sign a non-aggression pact, which did not prevent new tensions and a postponement of their departure; however, they finally set off on July 4, 1190, from Vézelay, where Philip II of France and Richard the Lionheart began their journey to the Holy Land.

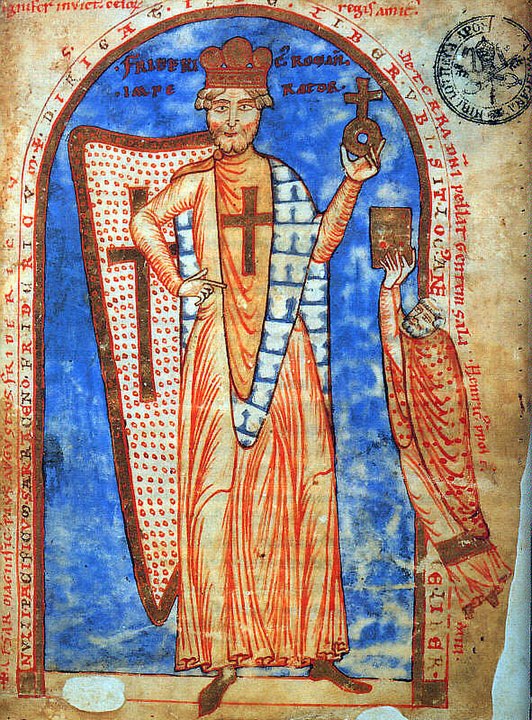

The Other Great Sovereign: Frederick Barbarossa

It would take too long to explain the circumstances of Frederick Barbarossa’s rise to the imperial throne, but it should be remembered that this followed the Investiture Controversy. Barbarossa had been in conflict with the papacy since the 1150s, and this continued into the 1180s, primarily due to the rivalries in Italy between the Hohenstaufens and the Guelfs, not to mention the Normans in southern Italy and Sicily! He had also been involved in the struggles between the Plantagenets and Capetians, often supporting Henry II.

In the early 1180s, the emperor had settled his affairs with the Lombard League at the Peace of Constance (1183) and definitively pacified rivalries within the Empire at Pentecost in 1184, where his power was recognized by most of the nobles. He decided to take the Cross at the Diet of Mainz in 1188.

The imperial army was by far the most impressive of the three royal armies heading for the Holy Land, with estimates of 100,000 men, including 20,000 knights! Frederick Barbarossa did not hesitate to challenge Saladin to a duel, and he marched decisively toward Jerusalem, without waiting for Richard and Philip. However, problems quickly arose due to the unwillingness of the other emperor, Isaac II Angelos of Constantinople, who had allegedly made deals with Saladin and imprisoned a German embassy.

Barbarossa then decided to ravage Thrace and force his eastern rival into cooperation; the Byzantine emperor had to relent and helped him cross the Dardanelles in March 1190. After a difficult journey through Asia Minor and two victories over Muslim armies, the emperor drowned while crossing the Saleph River! The great imperial army vanished with him, except for a few contingents that managed to reach Antioch.

Richard and Philip in Sicily

The English army reportedly numbered 850 knights, and the French army slightly more than 600. Although the two rival kings departed together from Vézelay, they then took different routes: Philip II of France sailed from Genoa, while Richard chose Marseille. The King of France arrived in Messina on September 16, 1190, and stayed in the royal palace; Richard made a grand entrance six days later, and the rivalry between the two men immediately resurfaced. Nevertheless, they remained in Sicily for six months! Tensions arose between the two armies, as well as with the local population, but in any case, it was the King of England who benefited; it was during these events that he was reportedly nicknamed “the Lion,” and Philip “the Lamb.

”

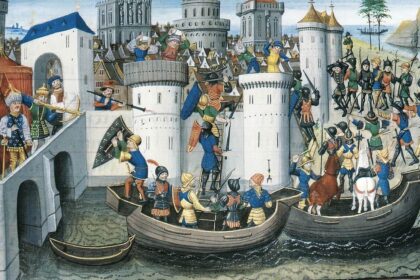

It also seems that a romantic issue arose, with Richard’s sister Joan, whom Philip had fallen for, as the central figure, and the main issue being the succession in Sicily. Tancred, cousin of the late William the Good and then ruler of the island, took advantage of the situation to strengthen his position by setting the two kings against each other. This led to the sack of Messina by the English army in October 1190, and Philip was deeply offended when he saw his vassal’s banners flying over the city walls; it is said that this is when he decided to seize Normandy later.

Despite attempts at compromise, tensions continued into the first half of 1191, exemplified by the case of Guillaume des Barres, a knight who managed to defeat Richard in a joust, provoking the latter’s fury and forcing Philip to dismiss him! Everything finally ended when Richard was allowed to break his promise to marry Philip’s sister, Alys, in order to marry Berengaria of Navarre, who arrived on the island accompanied by Richard’s mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine. It seems that an agreement was reached, and the two kings reconciled before continuing their journey.

From Cyprus to Acre

The king of France, however, prefers to leave Sicily before the arrival of Eleanor, and this is accomplished on March 30, 1191; he sets sail for Acre. Richard, who is getting married, will only be able to join him a month later due to a storm. This storm pushes him to the shores of Cyprus, and the fiery king sees this as a good reason to conquer the island! Since 1184, Cyprus had freed itself from Byzantine rule and become an autonomous state. It is held by Isaac Komnenos, who, jealous of his independence, does not hesitate to form an alliance with Saladin. He even goes as far as to threaten Berengaria of Navarre, whose ship had fallen into the hands of his troops, and Richard, faced with Isaac’s refusal to negotiate, decides to confront him in May 1191.

Richard defeats him easily, further increasing his wealth and fame.

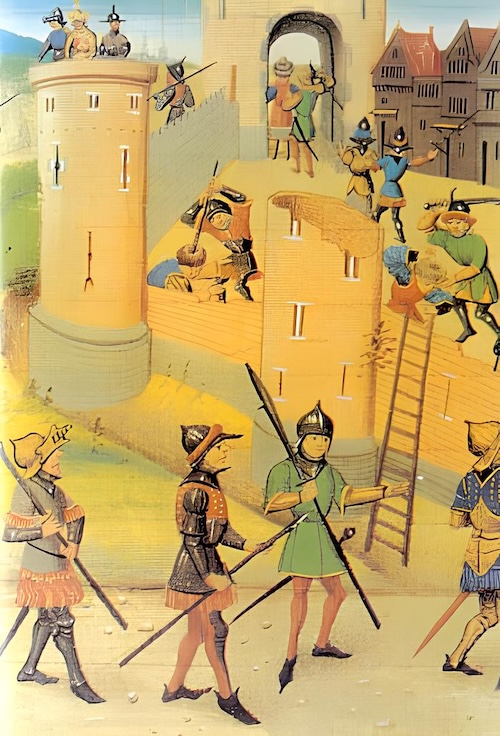

Upon arriving in front of Acre (taken by Saladin in the wake of his previous victories), Philip II of France finds himself in the middle of the rivalry for the succession to the throne of Jerusalem, as the Holy City has been reconquered by the Muslims. The rivalry between Guy of Lusignan and Conrad of Montferrat had been ongoing since the previous year, and the king of France sides with the latter. Richard’s army arrives to finish the siege of the city, which falls into the hands of the Crusaders on July 12, 1191.

Richard the Lionheart and Saladin

The matter of the succession to the throne of the Kingdom of Jerusalem is first settled, temporarily in favor of Guy, then in favor of Conrad, though not until 1192, and only briefly, as Conrad is assassinated. Guy is ousted in favor of Henry of Champagne but obtains Cyprus from Richard.

Meanwhile, Philip II of France realizes that he has no place in this crusade, where Richard’s overwhelming presence casts too much of a shadow. Rather than continuing to yield, and believing his duty fulfilled, he returns to France in early August! The future will prove him right, both against Richard and against his brother and successor, John Lackland.

Richard, however, continues his crusade, skillfully maintaining his reputation. His rivalry with Saladin begins to be talked about, and it intensifies following his victory against Saladin at Arsuf in September 1191, and then with the reconquest of Jaffa and Ascalon. The end of the year sees the first negotiations between the two men, although they never meet. Hostilities resume in the following weeks, but each time Richard hesitates to attack Jerusalem directly.

In September 1192, Richard learns that Philip II of France and his brother John are plotting behind his back in the West. Facing an aging and sick Saladin, he negotiates a truce of three years and three months, as well as free access to Jerusalem for Christian pilgrims. He leaves the Holy Land at the beginning of October 1192.

The Outcome of the Third Crusade

The outcome is mixed. While the Crusaders have reclaimed a few strongholds and gained access to Jerusalem, the remnants of the Latin states cannot be considered viable. Furthermore, the very image of the Crusade, after the failure of the previous one, is hotly contested in the West.

Politically, even for the Muslims, the result is relative: they have retained the essentials, and the status quo works in their favor, but Saladin faces increasing criticism. Weakened, he empties his empire’s coffers, leaving his successors in great difficulty when he dies in 1193. Rivalries resurface, again benefiting the Crusaders.

For the West, the consequences of this Crusade, even indirect ones, are significant. First, Richard is captured on his return by Leopold V of Austria; the latter had participated in the capture of Acre alongside him but felt humiliated when Richard refused to allow him to raise his flag alongside his and that of the king of France!

Richard is held for two long years and is freed only after a huge ransom is paid. During this time, his brother John plotted against him with Philip II of France. Richard forgives him, however, and resumes his war against his eternal rival; it is during a battle in Limousin that he is struck by a crossbow bolt and dies of his wounds in 1199. Subsequently, Philip II of France gains the upper hand over John, who has succeeded Richard.

The Third Crusade is therefore remembered primarily due to the legendary figures of Richard the Lionheart and Saladin, but also because of the rivalry between the Capetians and the Plantagenets in the West. The status quo achieved with Saladin will certainly prolong the presence of the Latins in the East, but the saga of the Crusades is far from over.