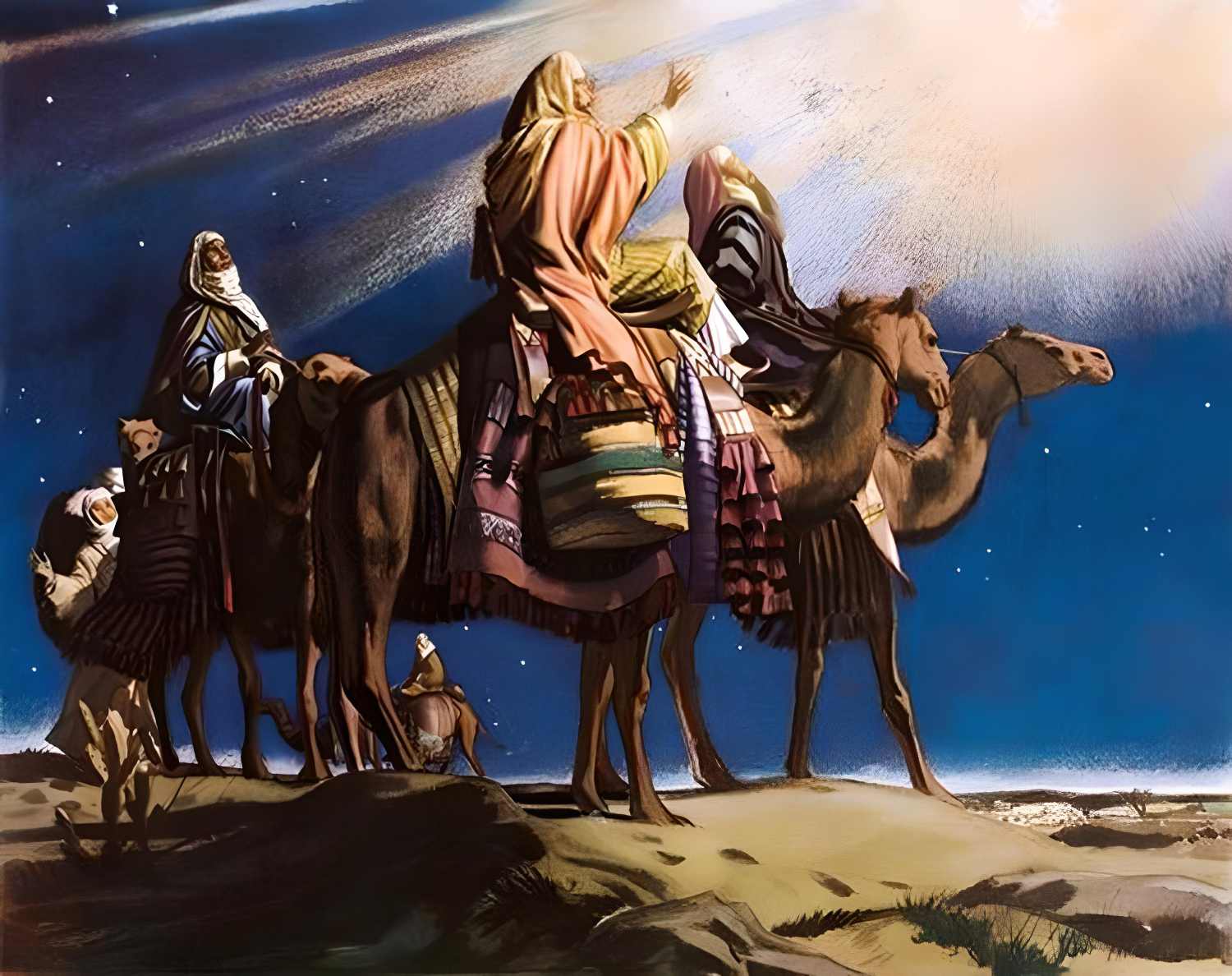

On January 6, religious Christians celebrate the day the Three Wise Men came to pay their respects to the Christ Child in Bethlehem. The Bible says that the men, sometimes known as the Biblical Magi or Three Kings, visited the infant Jesus with gifts. What kind of kings, if any, did they really play? And were there really three of them?

The origin of the Biblical Magi

This may disappoint the coral singers of the Epiphany, but the Bible says nothing about the number of the kings. The Greek word “magoi” (which is where the English word “magi” comes from) is the source for Matthew’s use of the term “wise men from the east” to describe the travelers who followed the star to Bethlehem to find the infant Jesus. According to the Gospel of Matthew, it was Roman Jewish King Herod the Great (b. 20 BC) who sent the wise men.

The Greek word “magoi” means a practitioner of magic, including even astrology. The word was used for the well-read and cultured men of the day, for whom stargazing or alchemy represented a scientific showdown with the cosmos. Therefore, “wise men,” as later translated by Martin Luther, was a better wording than the magi. The whole theme was that the foreign aristocracy was visiting the infant Jesus.

Popular in Christmas myths and rituals all across the globe, the Three Wise Men are generally shown as aged, wise men in traditional Christian art. It is often held that the three wise men story symbolized the three major faiths of the time—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—and that the presents they brought Jesus signified his three main functions as king, priest, and sacrifice, at least for the Christian scholars.

How many magi were there?

The idea that there should have been three magi is just an assumption with no historical value. The Biblical Magi brought three gifts: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. However, any number of individuals could deliver these three gifts. That is why some of the oldest murals about the Biblical Magi depict two men, while others have four. Only in the Middle Ages do the Biblical Magi become “three kings” or “three wise men.” One of the wise men had a dark complexion, and his name was Balthazar; his two companions’ names were Caspar and Melchior.

It’s not certain whether the Three Wise Men ever existed. Many Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) prophecies were used by Matthew to support the claim that Jesus was the promised Messiah. The story of the Three Wise Men from the East reads like a patchwork of many prophecies. The noblemen later became the focal point of Medieval Nativity scenes. Balthazar, the dark-skinned member of the pair, became a fan favorite and continues to be featured in dark skin as he was supposed to be of African origin.

The bones of the Magi

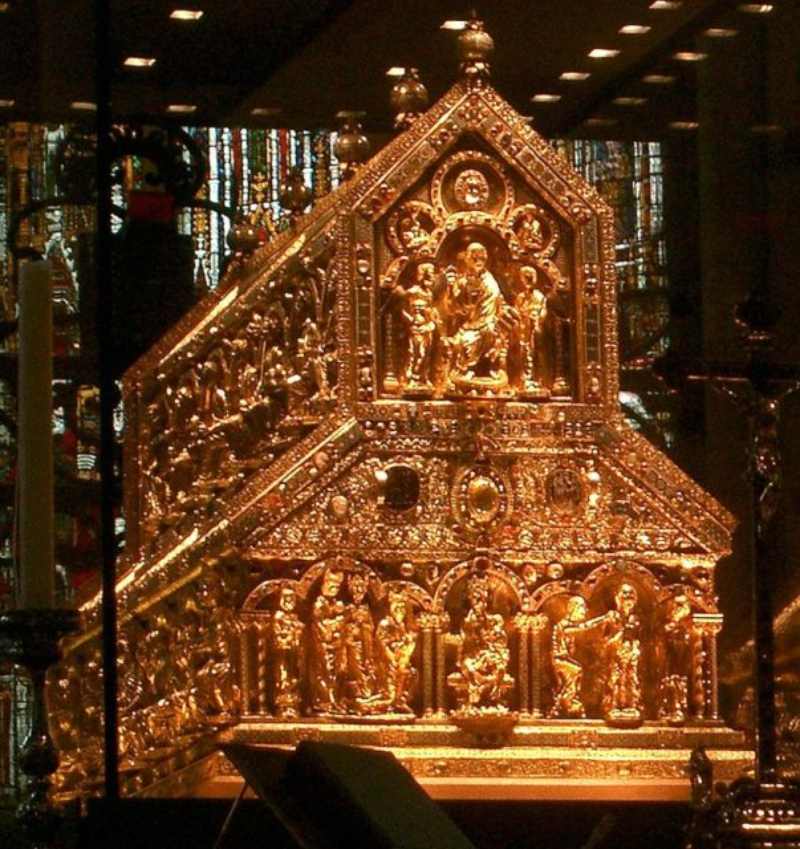

You may not need to go back in time if you want to pay a visit to the Three Wise Men. Christians believe that their remains are housed in the Shrine of the Three Kings, a golden shrine located in Cologne Cathedral in Germany. The Shrine of the Three Magi created around 1181-1230 by the goldsmith Nicholas of Verdun.

The remains were one of the Middle Ages’ most priceless artifacts of cultural significance. The Milan Cathedral was the first location where the bones were stored. The artifact was a war booty given to Rainald von Dassel, Archbishop of Cologne, by Frederick Barbarossa after the latter’s 1162 conquest of the city.

Three men of varying ages were determined to be the source of the bones when they were inspected in 1864 by an anatomist in Bonn. At first glance, this seems meaningless. But the bones are still among the oldest authentic Christian artifacts since they were found on a piece of 2nd-century Syrian fabric, indicating that they were treasured as relics at an early date anyway.

The chalking-the-door tradition

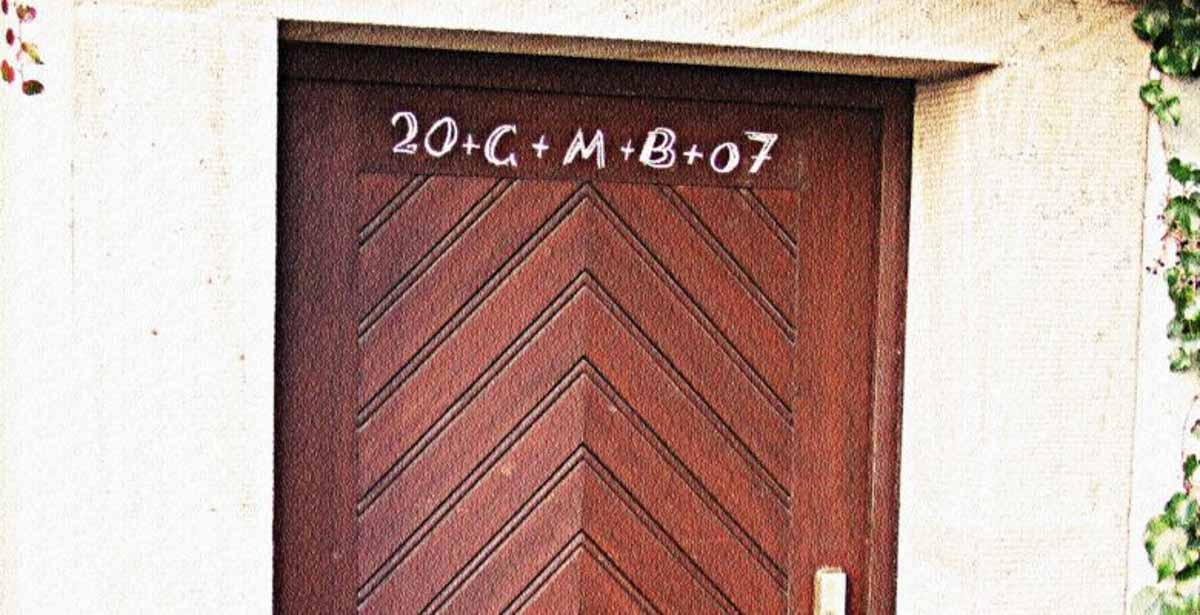

Whether or not the Three Wise Men existed, the mythology still motivates hundreds of kids every year to dress up as nobles and chant their way around neighborhoods in search of donations for charity. The year and the initials of the wise men are chalked into the doors on the Fest of Epiphany on January 6 as follows: 20*C+M+B+23 (for 2023).

In time, Christians also interpreted these initials to mean “Christus Mansionem Benedicat” in Latin, or “Christ, bless this house. This “chalking the door” tradition was also a Scottish way of telling renters they had to leave, until recently.

The origin of Epiphany

Today, one of Christianity’s earliest celebrations—Epiphany—is encapsulated in a tradition that has its roots in legend: God incarnates as Jesus Christ. Epiphany has its roots in the early Christians’ celebration of Christmas, which was more interested in the metaphor of light than the romanticism of a manger.

It’s possible that the first Christians appropriated and reinterpreted this feast from various religions and also the Roman Emperor Cult. Because the church in the Roman Empire accepted the popular celebration of the unconquered sun god (“Sol Invictus”) and its symbolism as Christmas on December 25.

Even though January 6 is not as significant a Christian holiday as Christmas or Easter, it is nonetheless observed as a holiday in various countries, from Argentina, Bulgaria, and Egypt to the United States or Finland.

For a long time, January 6, the day of Epiphany, was a major celebration day. Until the middle of the 20th century, the first day of school usually began later than January 6th after the winter break in western countries. Since the public was aware that Christmas celebrations often continued until at least January 6.

Bibliography

- Nigel Pennick (2015). “Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies.” Inner Traditions – Bear & Company.

- “An Epiphany Blessing of Homes and Chalking the Door”. Discipleship Ministries. 2007.

- Essick Amber, John Inscore (2011). “Distinctive Traditions of Epiphany” (PDF). 2016.