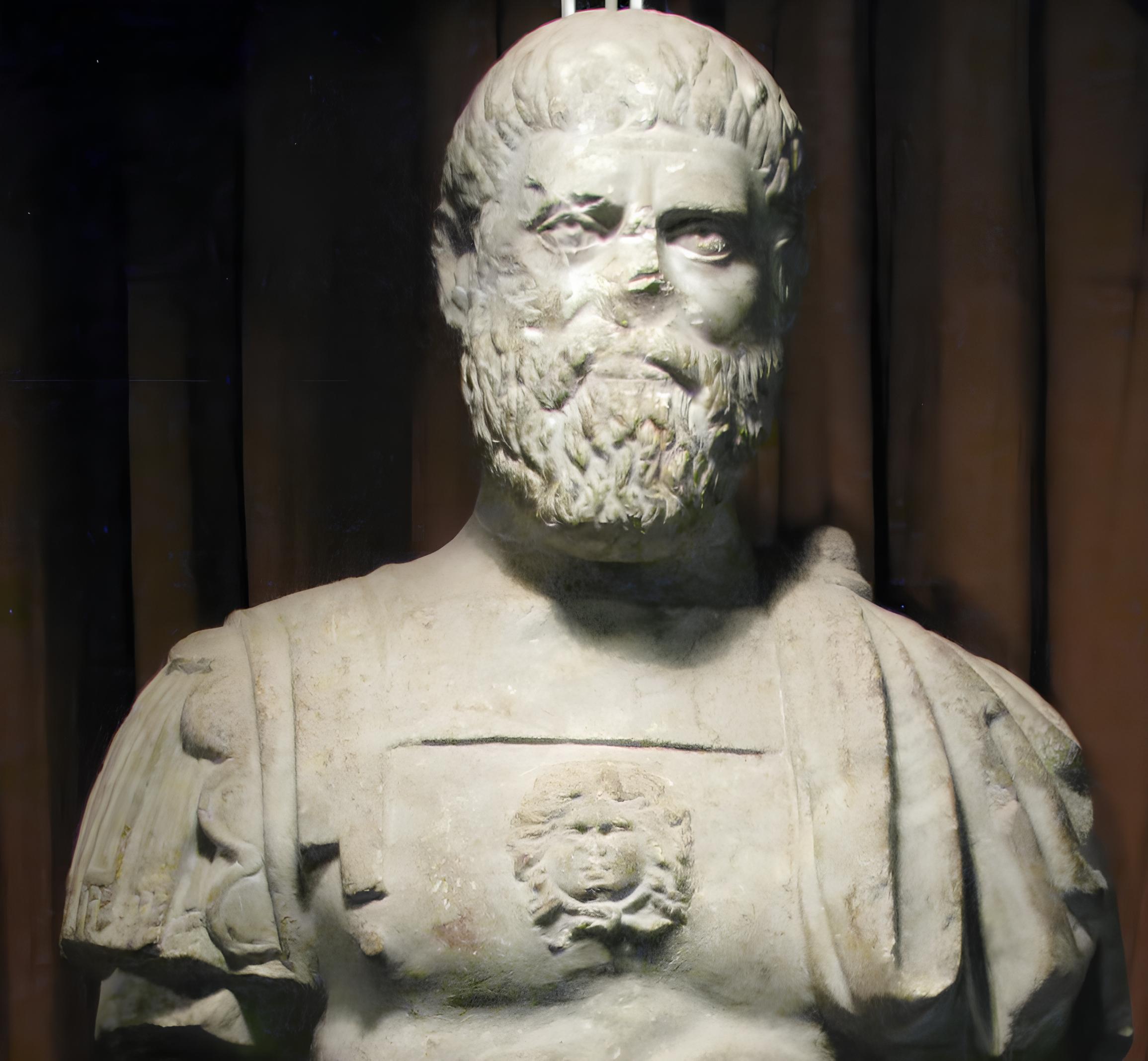

Tiberius Claudius Narcissus rose from slavery to become a prominent figure in ancient Roman politics in about the 1st century AD. With the support of Emperor Claudius, Narcissus rose from the ranks of Roman slaves to one of the highest levels of government. He served as a powerful imperial secretary and advisor to the Roman Emperor Claudius and made up the backbone of the imperial government. Just like other former slaves, he adopted the surname (“Claudius”) of his former master.

See also: The Price of a Slave in Ancient Rome in Today’s Dollars

A Roman Emperor Who Put Emphasis on Merit

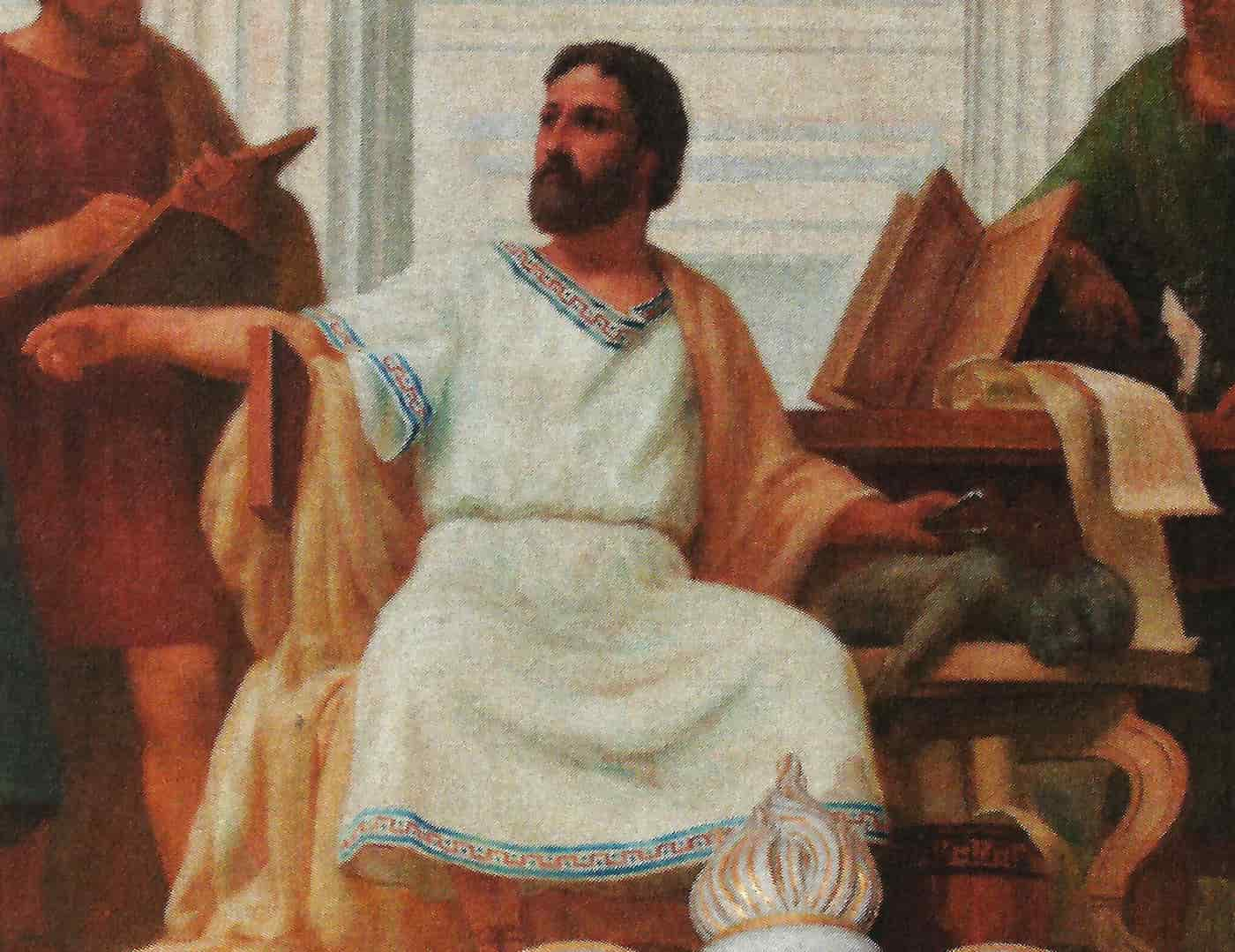

Many contemporary historians see Emperor Claudius as a “great prince.” He was very interested in politics, and he stressed the need for logic and change in government and the military.

Furthermore, to ensure the efficient administration of the ever-growing imperial government, he believed that appointing people to crucial positions solely based on their aristocratic lineage was not ideal. He advocated for capable bureaucrats who had proven their loyalty to the emperor through their talents and achievements.

As a “former slave,” Tiberius Narcissus was an ideal choice for Claudius. Because of his undying devotion to the emperor, Narcissus was given greater authority than anyone else. He gained a fortune through his considerable influence with the emperor.

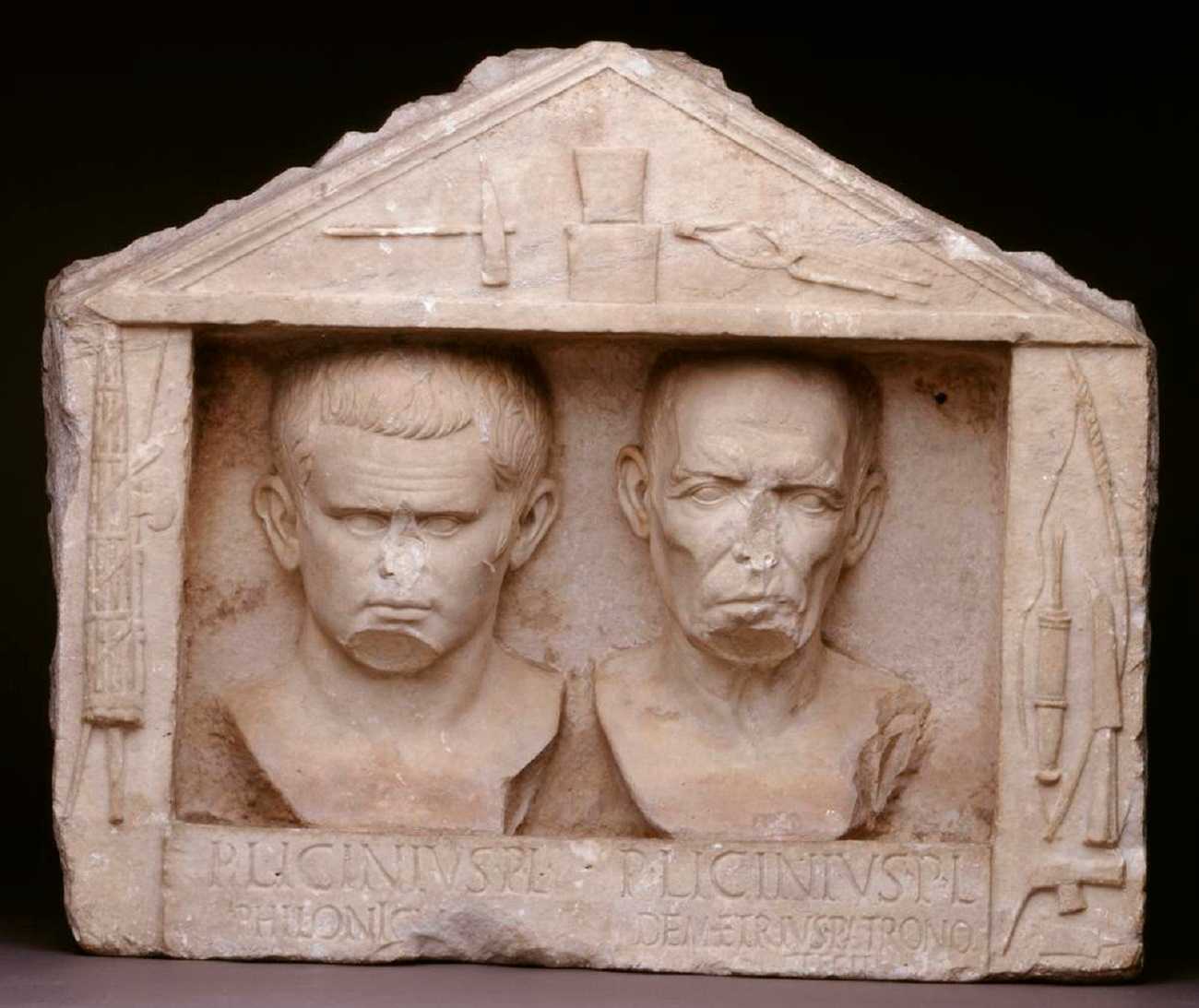

In ancient Rome, when an emperor released a slave, the former slave would be obligated to remain loyal to him out of gratitude and the customary sense of responsibility. Given their humble origins, it was also highly improbable for someone who was born into slavery and later freed to attain a prominent position within Roman authority.

See also: What Was Daily Life Like in Ancient Rome?

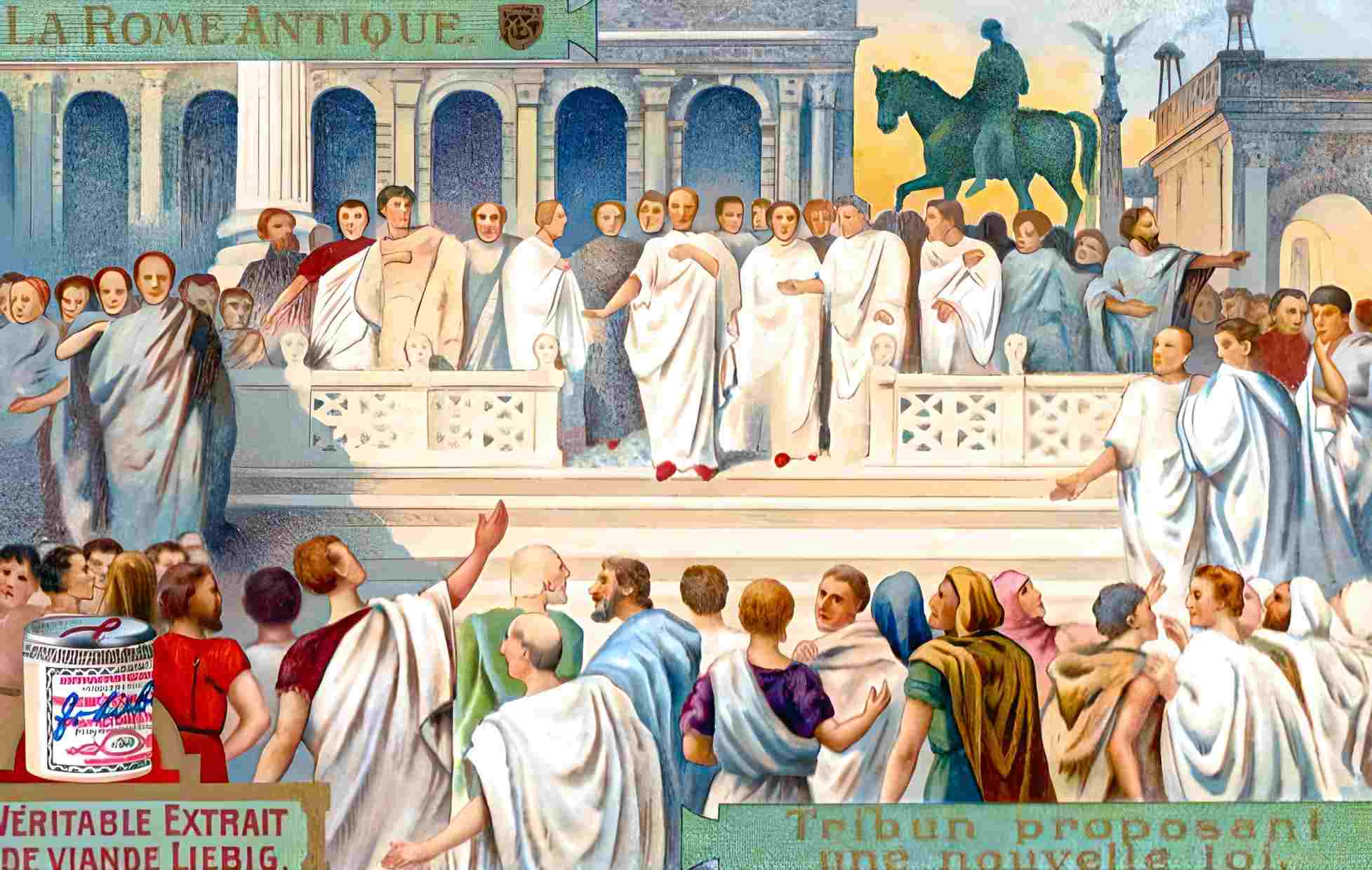

Ex-Slaves Ran the Roman Politics

Quick-witted, skilled ex-slaves ran the Roman politics around the emperor throughout Claudius’ reign, increasing both their number and their influence unlike anything witnessed in history before.

The political authority of the aristocracy was diminished, marking a transition from “emperor-bureaucratic centralization” to the establishment of absolute royal power.

The Roman nobility was the primary group to resist this change. It was believed that slaves had “stolen” politics, which was formerly the domain of aristocrats.

During Claudius’ reign, various assassination plots by aristocrats were uncovered, and Claudius murdered many of them, causing even greater animosity among the aristocracy.

See also: What Has Not Changed Since the Time of Ancient Rome?

Claudius had physical disabilities, as described by Suetonius: “His knees were weak; he faced difficulty walking; he stuttered often; and he experienced hearing impairment. He also had a tendency to drool and had a runny nose.” Recent research has pointed to cerebral palsy as a likely cause of these symptoms.

Although his intelligence was unquestionable outside of the realms of law and reform, many ancient nobles considered Claudius unsuitable to be emperor because of his infirmity.

That’s why most Roman historians often had a dim view of Claudius. However, one explanation for this is that the nobility were the ones who had the leisure time and resources to document the past. That’s why current scholarship agrees that he was “a very good ruler.”

See also: Was Julius Caesar a Good Leader? The Leadership of Caesar

Tiberius Claudius Narcissus: A Notable Ex-Slave in Roman Politics

The slave Tiberius Claudius Narcissus was a notable figure during the reign of Claudius. Tiberius Narcissus’ life is not well known, but we do know that Emperor Claudius bought him as a “former slave” and, after realizing his brilliance, set him free to work for the emperor as a government official.

He was Claudius’ right-hand man. So much so that his role as “Secretary Liaison” for the emperor gave Narcissus considerably more authority than his job description implied. He was responsible for a wide range of political choices.

For instance, Emperor Claudius’ greatest accomplishment, the “Roman Conquest of Britain,” included a tribute to Narcissus.

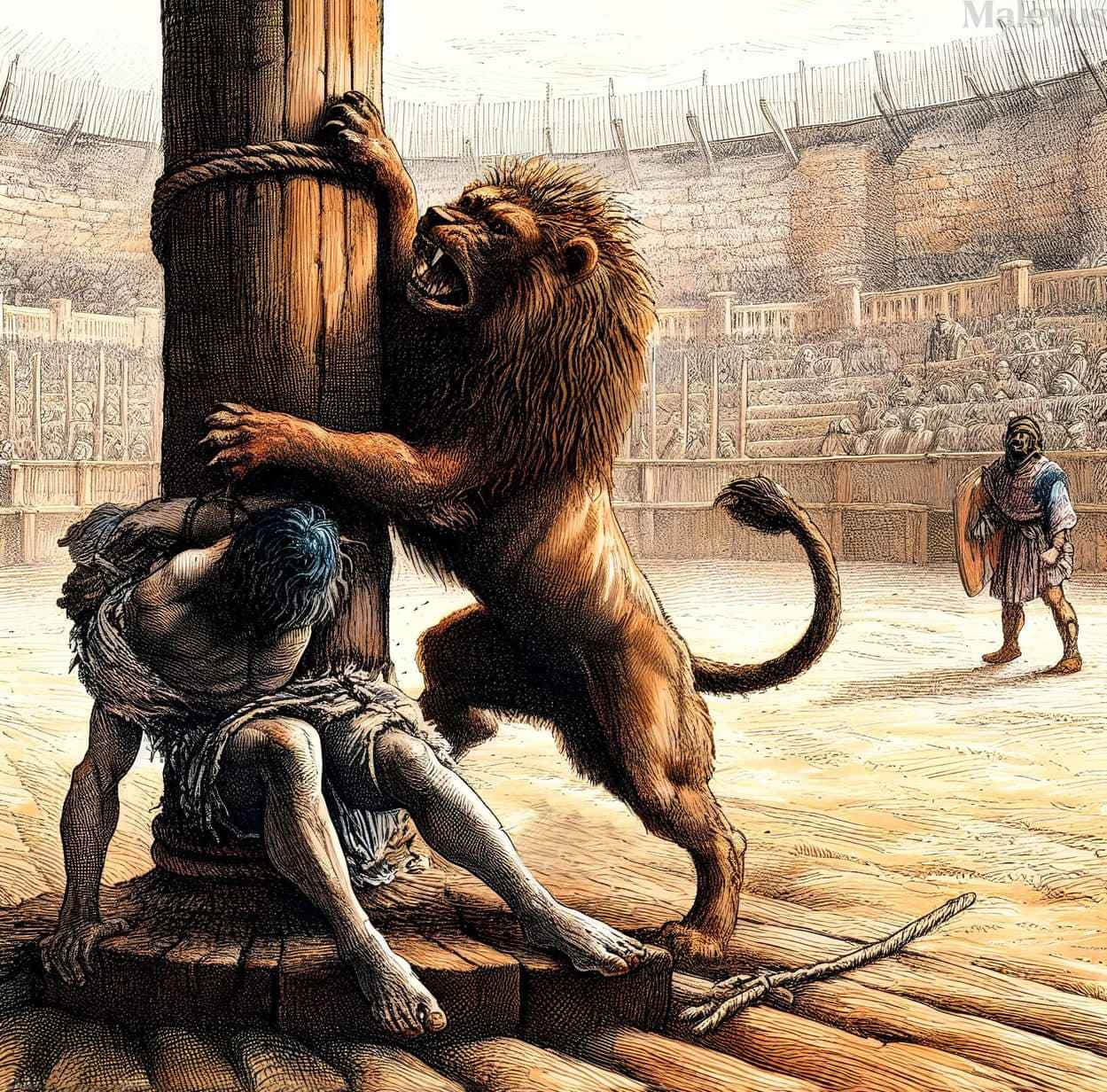

When the Roman army in AD 44 refused to go on an expedition to Britannia, the emperor sent Narcissus as his deputy to deal with the rebels.

Narcissus decided to taunt the soldiers and invoke the spirit of “Saturnalia,” a festival where slaves temporarily hold power over their masters. Witnessing a former slave now serving as their leader, Narcissus made the army put down the uprising and embark on the daring expedition in an extraordinary turn of events.

As part of the program of clearing the land, Tiberius Narcissus was also given the massive task of canalizing Fucine Lake in Italy to reduce the water level.

Britannicus and Nero in a Clash for the Throne

Claudius had a significant “successor problem” in his old age. The first and second wives did not produce any offspring, whereas the third wife did have a son (Britannicus). Unproven rumors suggest Narcissus plotted with Claudius’s third wife Valeria Messalina to have a number of individuals killed. On top of that, doubts arose regarding the legitimacy of the child due to Messalina’s infidelity coming to light, which led to the disqualification of her claim.

“Agrippina the Younger,” (15–59 AD) the emperor’s fourth wife, gave birth to “Nero,” who was a “candidate successor” in the lineage of the emperor since he was a fourth-generation descendant of Emperor Augustus via the maternal line.

There were two camps within Claudius’ bureaucracy: the “Nero faction” and the “Britannicus faction,” with Claudius and Britannicus at odds and Nero seen as his heir apparent. Britannicus was retained as a backup in case Nero was assassinated.

However, Narcissus did not have faith in the fourth empress and demanded that Claudius remove Nero’s inheritance, name Britannicus emperor, and install him.

The Death of Narcissus

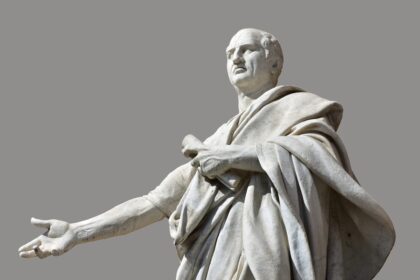

Agrippina, Claudius’ fourth wife, is widely believed to have plotted with the nobility to poison her husband so that Nero might ascend to power. However, contemporary scholarship suggests that Claudius may have died of natural causes. Nero, being just 17 years old, became Emperor upon the unexpected death of Claudius.

Agrippina, the emperor’s mother, had considerable power and quickly confronted Narcissus, the powerful leader of the Britannicus faction, whom the nobility despised. Without delay, Narcissus was arrested and sentenced to death, and within a few weeks of Claudius’ passing, he was executed by beheading in October, 54.

Before his arrest and death, he burned all of Claudius’ letters to prevent Nero from exploiting their contents.

Upon Nero’s ascension to the throne, Agrippina, who held significant influence, ruthlessly orchestrated a campaign to eliminate those who opposed Nero’s rise to power. As a result, Narcissus and numerous accomplished former slave officials appointed by Emperor Claudius met their demise, while Britannicus fell victim to poisoning.

Nevertheless, as time passed and Nero reached adulthood, he grew increasingly dismissive of his mother’s involvement in political matters, leading to Agrippina’s diminishing influence. Moreover, due to her opposition to Nero’s mistress, Nero made the drastic decision to have his own biological mother executed.

Nero had a disdain for advisers who offered dissenting opinions and systematically removed them from his circle. He surrounded himself with individuals who flattered him, and as a result, the empire’s finances rapidly deteriorated, cementing his name as one of the most notorious tyrants in Roman history.

Eventually, a nobility-led uprising would result in Nero’s death. He was the last direct descendant of the Julio-Claudian dynasty to hold the title of emperor.

Historians have long overlooked Claudius and Narcissus. Even though he was held in low regard by noble historians of the time, Claudius had his share of successes and shortcomings. To further his own interests, Narcissus ingratiated himself with the emperor, assumed political power, and became a man who rose from slavery in ancient Rome.

Recent studies have shed light on the “prejudice” of early historians and led to a reevaluation of Claudius’ accomplishments, including his policy reforms, legal reforms, and conquest of Britannia. This reevaluation also sheds light on the ex-slave Narcissus’ life.

The verdict of history remains enigmatic.

In passing, it’s also widely believed that the influential Roman Emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305 AD) was himself the child of a slave.