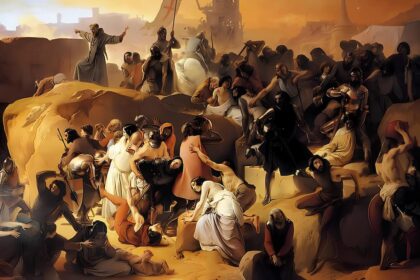

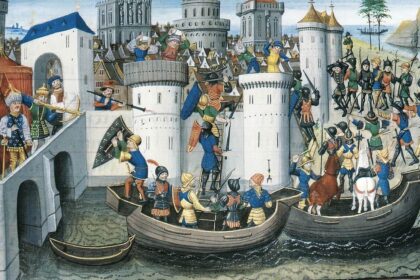

Travelling to the Time of the First Crusade

The First Crusade began in 1096 and lasted until 1099, spanning a period of about three years. It was initiated by Pope Urban II in response to the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I's appeal for military assistance against the Seljuk Turks, who had captured Anatolia and threatened Constantinople.