The Treaty of Tordesillas, which was signed on June 7, 1494, defined Spain’s and Portugal’s overseas territories and created an illustrative border across the Atlantic Ocean west of the Cape Verde Islands. For the first time in history, a border was established that divided the world, denying rights to any other nation. John II of Portugal and the Catholic Kings agreed to divide the uncharted New World under the terms of this contract, which was confirmed by a papal bull. No rights to these new regions were granted to the other maritime powers in Europe. Francis I requested to look at “the clause in Adam’s will which excluded him from his share when the world was being divided.” During the Tordesillas negotiations, the peoples of Amerindians, Africans, and Asians were not consulted.

A Globe, Consisting of Portugal and Spain

In quest of a new trade route to Asia in the middle of the 15th century, Portugal constructed commercial ports along the African coast and set sail towards the Atlantic Ocean. Asia’s door was opened by the Portuguese expedition led by Bartolomeu Dias’s transit of the Cape of Good Hope, the entrance to the Indian Ocean, in 1488. However, Spain, a growing force in Europe, quickly began to compete with Portugal. Following the formalization of the Treaty of Alcáçovas signed in 1479, Portugal was compelled to renounce its territorial claims to Isabel the Catholic during the years 1480–1490.

More than anything else, Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the Americas heightened the urgency of drawing a border between the two Iberian Peninsula nations. The line of “demarcation” from pole to pole was established 100 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands by Pope Alexander VI in 1493 in his first Bull. Although the Portuguese monarch requested that this line of partition be renegotiated the next year, it was a triumph for the Spaniards. The debates started at Tordesillas, in the province of Valladolid, in May 1493.

The Treaty of Tordesillas

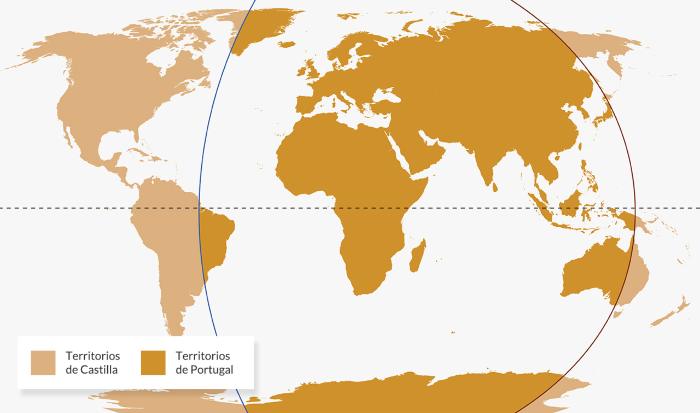

The demarcation line between Spain and Portugal’s future overseas possessions was set by the Treaty of Tordesillas, which was signed on June 7, 1494, by the Catholic Monarchs and John II of Portugal. Pope Alexander VI had set this line in 1493 at 100 leagues west of the Azores and Cape Verde, but the Portuguese requested that it be postponed to 370 leagues. Any new territory found east of this line belonged to Portugal, while any new land discovered west of this line belonged to Spain. In 1506, Pope Julius II gave his blessing to the Tordesillas Treaty (Inter Caetera). In the future, all areas found to the east of the aforementioned line would belong to Portugal, while all lands discovered to the west would belong to the Spanish crown.

The agreement granted Portugal exclusive access to the most sought-after trade routes, those that led to the priceless spices of the East, in exchange for the establishment of commercial outposts in Asia and along the coasts of Africa. Tordillas’ adjustment gave Portugal possession of the American continent, enabling it to establish Brazil, the only colony of the little Iberian monarchy.

After that, Spain was able to assemble a vast empire from Mexico and Peru and took the lead as the dominant European power. While boosting the economy of the old continent, the silver and gold that streamed in from America helped it pay for its conflicts in Europe. In the year 1550, nearly the whole of South America, Central America, Florida, Cuba, and the Philippines in Asia were under Spanish authority.

The Treaty Was Rapidly Challenged

The two countries made changes to the Tordesillas Treaty as early as the 16th century. The Portuguese colony in Brazil would eventually spread well beyond the line of demarcation, and Spain annexed Ternate and the Philippines in Asia, although they were still part of the Portuguese domain. Utilizing a contract that resolved a conflict over Brazil’s southwest boundary, the demarcation line and all the agreements associated with it were abolished in 1750. Later, in 1761, the 1750 pact was revoked. A new treaty was signed between the two nations in 1779 to resolve any further disputes.

The various treaties that Spain signed with the papacy and Portugal were of little importance to the maritime nations of northern Europe (England, France, and the Netherlands), so starting in 1520, a growing number of their merchant ships began sailing into the Caribbean Sea, bringing slaves from Africa to the larger islands. As new colonial empires arose in their spheres of influence as defined by the Treaty of Tordesillas, Portugal, and Spain, both in decline, could only watch helplessly throughout the seventeenth century.

Bibliography

- Roland Chardon, “The linear league in North America“, (1980).

- Horst Pietschmann, Atlantic history: history of the Atlantic System 1580–1830, (2002).