Charlemagne, son of Pepin the Short, was anointed Western Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800. It was under his rule that the Carolingian Empire flourished and expanded to include most of present-day Western and Central Europe. Charlemagne’s political legacy, however, did not survive him for long. After the death of his son Louis the Pious in 840, the empire was divided among his three grandchildren. Soon after, Lothar I, Louis II, and Charles II went to battle with one another over who would succeed as king. The fratricidal conflict between the three ended with the ratification of the Treaty of Verdun in August 843, which split the Carolingian Empire into three separate kingdoms.

Why was the Treaty of Verdun signed?

When the Western Roman Empire collapsed in 476, it was replaced by a patchwork of barbaric kingdoms. During the High Middle Ages, the Franks established the Carolingian Empire in Gaul following three centuries of territorial growth. When he was anointed emperor in 800, Charles I, commonly known as Charlemagne, expanded his kingdom’s frontiers and brought it to its zenith. However, since Clovis, it was customary for the heirs to break up the kingdoms. The Frankish Empire was split among Charlemagne’s three sons when his son, Louis the Pious, died (June 29, 840).

As a result, a bloody civil war broke out over who would succeed the king. Louis the German and Charles the Bald formed an alliance to counter their more powerful brother, Lothair I, who had become emperor. At the Battle of Fontenoy on June 25, 841, they were victorious over him and his nephew, Pepin II of Aquitaine. Lothair I accepted a compromise on February 14, 842, in the face of resolute opponents who had reinforced their alliance with the oaths of Strasbourg. With his brothers, he signed the Treaty of Verdun in August 843.

Who signed the Treaty of Verdun in 843?

Following traditional Frankish practice, Louis the Pious’ three sons split the Carolingian Empire in 840.

- Lothair I, the eldest

- Charles the Bald

- II. Ludwig (Louis the German)

The three grandchildren of Charlemagne finally convened in August 843 to sign the Treaty of Verdun after years of civil strife. However, the exact date of the signing remains unknown to this day. In all likelihood, it must be ratified in Verdun between August 8 and 11, 843. Not only had the date been deleted, but so had the content. As a result, the contents of the Treaty of Verdun are unknown since neither an original nor a duplicate survives. Nithard, grandson of Charlemagne, provided the bulk of the document’s details via his daughter Berthe’s writings. This episode is also vaguely recounted in the Carolingian era’s Saint Bertin and Fulda chronicles.

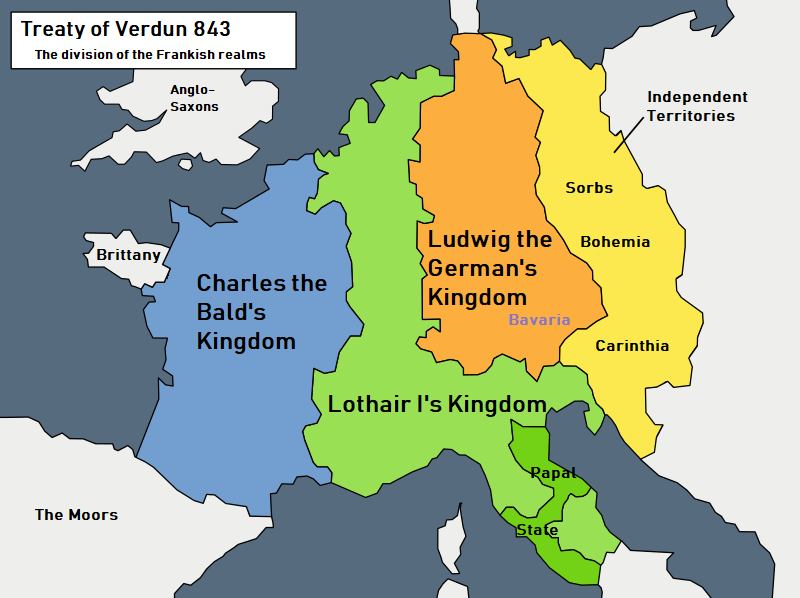

The division of the Carolingian Empire

The huge areas captured by Charlemagne’s grandson were divided up at the Treaty of Verdun. This resulted in the final partition of the Carolingian Empire into three major nations.

- West of the line formed by the rivers Scheldt, Meuse, Saône, and Rhone, Charles II was given the region now known as West Francia (with Paris as its capital). It included the regions formerly known as Neustria and Aquitaine, as well as the western portion of Austrasia and northern Burgundy.

- Louis II made Regensburg the capital of his eastern imperial province, East Francia. Bavaria, Saxony, the Alemannic and Franconian provinces, and the eastern half of Austrasia were all included.

- The oldest son, Lothair I, was given Middle Francia (also known as Lotharingia) and the imperial title. The latter reached from the North Sea province of Friesland to the Mediterranean. Part of this region was encircled by the kingdoms of his brothers; thus, it also comprised the Low Countries, the Rhineland, Burgundy, Provence, and Northern Italy. Rome, the home of the Catholic Church, was also the religious capital of the country, in addition to the political capital of Aachen.

The borders of the Treaty of Verdun evolved over time

At the time of the treaty of Verdun, the borders of the Carolingian Empire were set. However, they did not stay the same for very long. When Lothaire I died in 855, the Treaty of Prüm split middle Francia among his three sons. Louis II, who was the oldest and was called “the Younger,” got the southern part, which included the kingdom of Italy, and the imperial crown. Lothair II got the northern part, which became known as Lotharingia. Last, Charles, the youngest, got the center, which was made up of Provence and Cisjurane Burgundy (Lower Burgundy).

After Lothair II died in 870, a new division of middle Francia was put into place. Charles II the Bald and Louis the Germanic were his uncles. They signed the Treaty of Meerssen and split Lotharingia between them. After his nephew Louis II died in 875, Charles II became emperor of the West and took back control of the kingdom of Italy. By the Treaty of Ribemont in 880, his grandchildren gave Lotharingia to Louis the Younger, who was Louis the Germanic’s son. With this text, West Francia got back almost all of its borders from 843.

The results of the Treaty of Verdun

The hope of reuniting the empire was finally snuffed out with the Treaty of Verdun, which officially ended the Carolingian Empire. It set the stage for medieval Europe by splitting the enormous Frankish realm into three separate states. This agreement also constituted the birth of the French and German nations.

Before its eventual transformation into France in 1205, Gaul was known as “West Francia.” It was also possible to argue that Louis II was the first German king. His realm of East Francia would form the nucleus of the future Holy Roman Empire for decades.

Unfortunately, these nations’ populations were too different from one another linguistically and culturally to come together until much later. The feudal system that emerged in Europe throughout the Middle Ages can also be traced back to the Treaty of Verdun. As the number of Viking raids increased, the power of nations declined, benefiting the fiefs. Locally, the lords became de facto rulers once the monarch was deposed. From the 10th century forward, a feudal society gradually replaced the clientelism of the Merovingians and Carolingians.

MAIN DATES OF THE TREATY OF VERDUN

June 20, 840: Death of Louis the Pious

Louis I, also called “the Pious,” was born to Charlemagne and Hildegard of the Vinzgau in 814, and he eventually rose to the position of Western Emperor. During his rule, he faced several dangers, including Viking invasions and, in 830, a rebellion by his sons who wanted to succeed him. On 6/20/840, he passed away at Ingelheim, close to Mainz. After his death, his three sons, Charles, Louis, and Lothair, split up the Carolingian Empire. It didn’t take long for the fighting to start up again.

June 22, 841: The Battle of Fontenoy and the division of the Empire

Lothair I, who had been co-emperor with his father since 817, became sole emperor after his father’s death. Charles the Bald and Louis the Germanic banded together to oppose him because they both refused to acknowledge him as suzerain. At the Battle of Fontenoy in Burgundy on June 25, 841, Charlemagne’s grandsons fought over who would inherit the Carolingian throne.

It was a difficult war, but the two younger sons ultimately prevailed against their elder brother and nephew, Pepin II of Aquitaine. After signing the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the Empire was split into three separate kingdoms.

February 14, 842: Oaths of Strasbourg

Taking the vows of Strasbourg eight months after their triumph in Burgundy, Charles and Louis united to fight Lothaire. When the Carolingian Empire was split in two on February 14, 842, an oath of mutual support was signed between the two brothers. Louis made his commitment in Romance, the language from which French evolved, so that Charles’ troops would understand him. Charles repeated his phrases in Theodiscus, the proto-Germanic language. The oaths of Strasbourg, penned by their cousin Nithard, were the first official papers written in a widely spoken language other than Latin.

August 843: The Treaty of Verdun

Lothair, Charles, and Louis ended their animosity with a compromise the next year, thanks to the vows they took in Strasbourg. In August 843, the three sons of Louis the Pious signed the Treaty of Verdun, dividing the Carolingian Empire among themselves. Lothair retained the emperor title, though it was now only ceremonial and restricted to the kingdom’s core, which was medieval France.

The western part of Francia, which became known as France about the year 1200, was passed on to Charles, while Louis acquired the eastern part, which became the heart of the Holy Roman Empire and Germany.

November 22, 845: Independence of Brittany

Although the Breton duke Nominoe had declared his support for Charles II during the civil war, he eventually rebelled against his suzerain. At Ballon, close to Redon, on November 22, 845, he triumphed over the Franks. This triumph marked the beginning of the 700-year reign of Brittany as a cohesive and autonomous nation. They called Nominoe Tad ar Vro (“father of the country”) because he freed his people. When he passed away in 851, his son Erispoe became king of Brittany with the support of Charles II.

April 10, 879: Death of Louis II, the Stammerer

Louis II, often known as “the Stammerer,” became king of West Francia in 877. He was born to Charles II and Ermentrude of Orleans. In 879, on April 10th, after just 16 months in power, he passed away. He was 33 years old. His sons, Louis III of Neustria and Carloman II of Aquitaine and Burgundy, took the thrones after him.

The two brothers joined forces with their cousin Louis III, king of East Francia, to combat the Normans. At the Treaty of Ribemont’s signing in 880, they handed over Lotharingia to him. This redrawing of boundaries between the two realms would stand throughout the Middle Ages.

Bibliography:

- Oebele Vries, “Friesland”, Medieval Germany: An Encyclopedia (Routledge, 2001), pp. 252–56.

- Charlemagne and Anglo-Saxon England, Joanna Story, Charlemagne: Empire and Society, ed. Joanna Story, (Manchester University Press, 2005), 195.

- Pouzet, Philibert (1890). La succession de Charlemagne et le traité de Verdun. Paris. p. 72.

- La succession de Charlemagne et le traité de Verdun de Ph. Pouzet et E. Leroux, 1890.

- Histoire de France : des origines à l’an 2000, éd. Tallandier, 1998.

- Jean-Charles Volkmann, Chronologie de l’histoire de France