Vercingetorix, also known as Vercingetorix in Latin (circa 82 BCE–46 BCE), was the leader of the Celtic tribe Arverni in central Gaul, opposing Julius Caesar in the Gallic War. His name in Gaulish means “ruler over” (ver-rix) and “warriors” (cingetos). He was the son of the Arverni leader Celtillus, who was executed on charges of aspiring to rule over all of Gaul. According to some accounts, Vercingetorix received his education in Britain under the Druids. Dion Cassius testified that he was once a friend of Caesar.

Outbreak of the Vercingetorix’s Rebellion

During the Gallic War, Vercingetorix led a rebellion of united Gallic tribes against Caesar, who had effectively subdued the entire Gaul by 52 BCE. Caesar described the rise of Vercingetorix as follows:

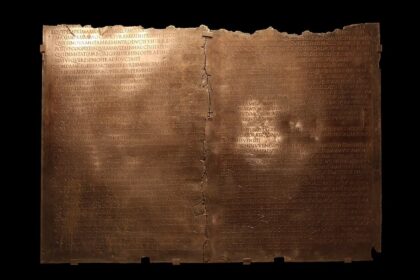

“This highly influential young man, whose father once led all of Gaul and was killed by his fellow countrymen for his desire for kingly power, gathered all his dependents and easily incited them to rebellion. Upon learning of his intentions, the Arverni took up arms. His uncle Gobannitio and the other chiefs, seeing no opportunity to try their luck at that moment, opposed him, and he was expelled from the city of Gergovia. However, he did not abandon his intention and started recruiting the poor and riffraff from villages. With this band, he roams through the community, attracting supporters everywhere, urging them to take up arms for the struggle for common freedom. Amassing considerable forces in this way, he drives his opponents out of the country, those who had recently expelled him. His followers proclaim him as their king. He sends embassies everywhere, urging the Gauls to keep faith with their oath. Soon, the Senones, Parisii, Pictones, Cadurci, Turones, Aulerci, Lemovices, Andes, and all the other tribes along the Ocean join him by unanimous decision. By their unanimous resolution, they entrust him with supreme command. Invested with this authority, he demands hostages from all these communities; he orders them to provide a specified number of soldiers in the shortest possible time; he determines how much weaponry each community should manufacture within a given period.

buy methocarbamol online http://mediaidinc.com/scripts/js/methocarbamol.html no prescription pharmacy

” — Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), Book VII, 4.

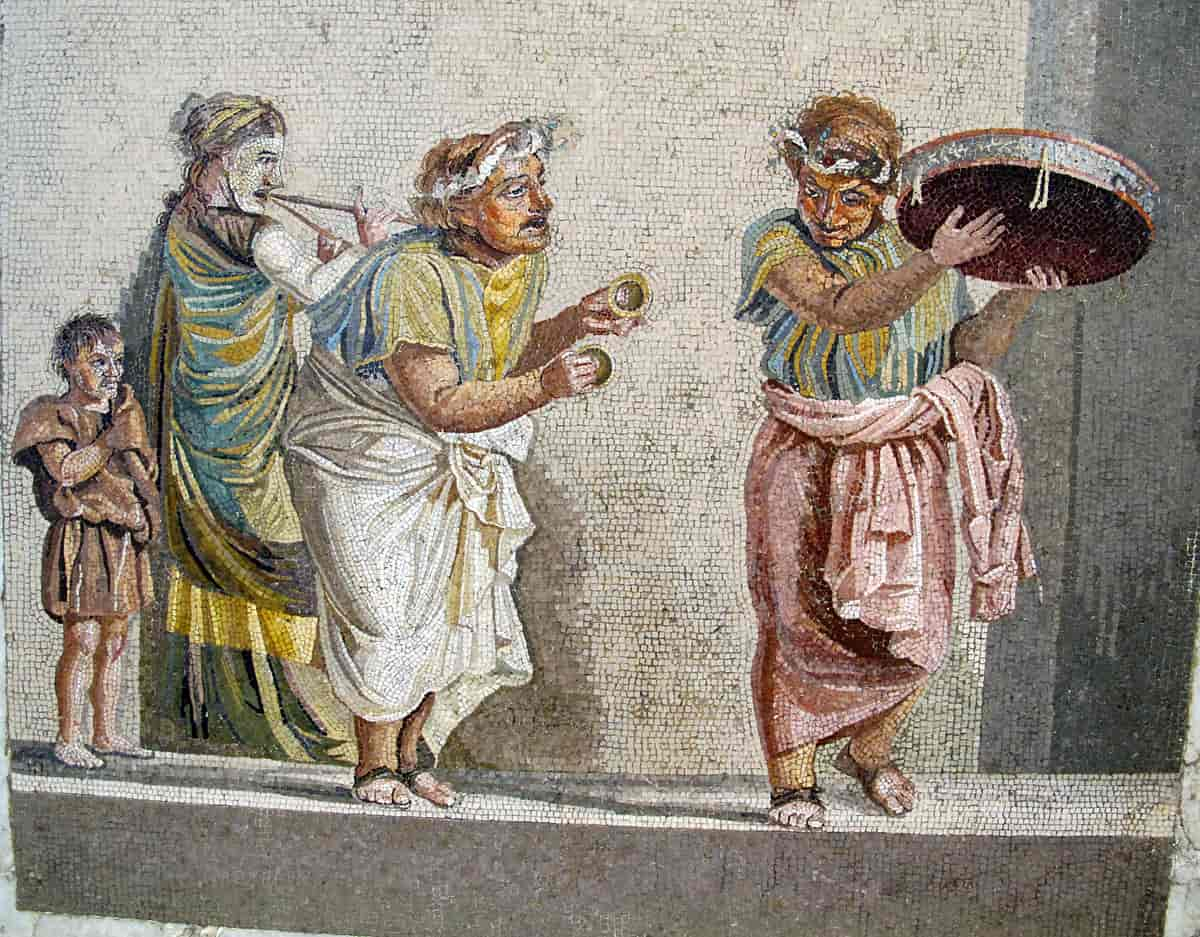

The signal for the uprising was the attack by the Carnutes tribe on Cenab (or Kenab, modern-day Orleans) and the killing of all the Romans in it, mainly traders. The attackers hoped that the Roman Republic, engulfed in a political crisis after the assassination of the politician Publius Clodius Pulcher, would not be able to react effectively. Robert Étienne suggests that Vercingetorix not only became the leader of the rebels before the massacre in Cenab, but also planned the entire rebellion, including the unusual start of the war in winter.

This forced Caesar, who was wintering to the south of the Alps under different circumstances, to traverse the snow-covered Cevennes mountains (Caesar writes about a snow cover height of 6 feet – about 170–180 centimeters) to reach the stationed legions in Gaul. The Gaulish leader’s plan was to block the Roman legions in the north and invade Narbonese Gaul in the south. According to this plan, Caesar would have had to divert all his forces to defend the Roman province, while Vercingetorix with the main army could act unhindered in central Gaul.

Having invaded the lands of Vercingetorix’s native tribe, the Arverni, Caesar left Decimus Brutus with cavalry there and, through the lands of the Aedui who remained loyal to Rome, reached two legions wintering among the Lingones. From there, he called the remaining legions from the territories of the Belgae.

Thus, Caesar managed to secretly reach his main forces, and Vercingetorix learned about it when the Roman forces were almost united. In retaliation, the Gallic leader attacked the Boii tribe, whom the Aedui had resettled in their lands. This compelled Caesar to make a difficult choice: either the commander started a campaign in the continuing winter, guaranteeing supply difficulties, or he refused assistance to the Boii, risking the confidence of Rome’s allies that Caesar could protect them.

The Roman commander decided to come to the aid of the Boii despite the expected difficulties. Leaving two legions in Agendicum (modern-day Sens), he besieged one of the main cities of the rebellious Senones, Vellaunodunum (location unknown), and took it in two days. The swift capture of the city was a surprise to the Carnutes, who had not prepared Cenab for the arrival of the Romans. The city was stormed and razed to the ground, and its inhabitants were sold into slavery as punishment for aiding in the killing of Romans.

After taking Cenab, the Romans crossed the Loire and approached Noviodunum of the Bituriges (modern-day Nevers-sur-Bévron or Neuvy-sur-Barangeon). Its inhabitants were ready to open the gates to Caesar when Vercingetorix’s forces appeared, and the Gauls changed their minds. However, after the advancing forces of the rebels (it was a small advance guard) were defeated by the Romans, the settlement’s residents still opened the gates to the Romans.

“Scorched Earth”

As Julius Caesar recounts in his “Commentaries on the Gallic War,” Rome secured its dominance over Celtic tribes beyond the Roman province of Narbonese Gaul by employing the “divide and conquer” policy. In contrast, Vercingetorix united the tribes and employed a tactic of attacking Roman forces followed by a strategic withdrawal to natural fortifications. Moreover, the uprising became one of the first documented instances of using the “scorched earth” strategy, where the rebels burned urban settlements to deprive Roman legions of provisions.

The Gaulish leader ordered all food supplies to be transported to a small number of well-defended cities, while demanding the burning of all other settlements and reserves to prevent them from falling into the enemy’s hands. Delaying tactics worked in favor of the Gauls, allowing them to continue gathering reinforcements and collecting provisions in remote areas.

Vercingetorix announced this decision at a meeting of leaders from the rebellious Gallic tribes.

The final exhaustion of all Roman food supplies was averted only by capturing another Gallic city — the capital of the Bituriges tribe, Avaricum (modern-day Bourges), where the Gauls stockpiled food. The Bituriges tribe pleaded with Vercingetorix not to abandon but to defend the city, which was well-fortified and situated amid impassable swamps, forests, and rivers. Despite this, Caesar decided to capture it upon learning about the substantial food reserves in the city.

For the assault, he chose a location between two swamps and began constructing ramparts, covered galleries, and siege towers. By mid-April, when the Romans were running out of food, the rampart was completed, allowing them to breach the wall. During the assault, Caesar’s forces, along with his deputy Titus Labienus, seized the city with abundant food supplies, and almost the entire population hiding there was slaughtered (out of 40,000, only 800 survived). However, the capture of Avaricum did not diminish Vercingetorix’s authority as a commander; it had the opposite effect:

“…since he [Vercingetorix] had previously, when everything was going well, proposed first to burn Avaricum and then to leave it, their [the Gauls’] estimation of his foresight and ability to foresee the future increased even more.” — Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), Book VII, 30.

Victory at Gergovia

Soon, Caesar divided his forces into two parts. He directed Titus Labienus with four legions to the north, into the lands of the Senones and Parisii, while he himself headed south, into the territory of the Arverni. The proconsul ascended along the Elaver River (modern-day Allier), whereas Vercingetorix followed the opposite bank, destroying bridges and preventing Caesar from crossing. Outsmarting the Gallic commander, Gaius crossed the Elaver and approached the Gallic stronghold in the lands of the Arverni – Gergovia (near modern-day Clermont-Ferrand). Gergovia was one of the key cities of the rebels, and Robert Étienne even calls it the “capital of the risen Gaul.”

The city was strategically located on a high hill and well-fortified. Although it was defended by Vercingetorix’s main army, Caesar decided to seize this strategically vital point. However, it soon became known that the leaders of the Aedui tribe were preparing to betray the Romans and join the side of the rebels. A 10,000-strong auxiliary detachment, which the Aedui had sent earlier to assist Caesar, wanted to switch sides to Vercingetorix due to rumors that Romans had killed all Aedui in their camp. Gaius learned about the spreading rumors and sent his cavalry to this detachment, including Aedui who were believed to be dead. Following this, the majority of the auxiliary detachment joined Caesar, but the Aedui tribe itself continued to lean towards an alliance with the rebels.

The subsequent events, known as the Battle of Gergovia (June 52 BCE), are not entirely clear due to the evasiveness of the “Commentaries.” Presumably, the unclear description was deliberately crafted by Caesar to absolve himself of blame for the failure. The general course of events is reconstructed as follows: the commander directed his forces in a risky assault, diverting the besieged’s attention with various tactics, but the attack was eventually thwarted. Caesar probably managed to achieve the element of surprise, but the besieged were able to concentrate their forces at the point of the assault in time.

According to the “Commentaries,” at the crucial moment, the legions did not hear the signal to retreat. However, this description does not explain why the troops needed to retreat if the assault was going well. Moreover, it is unclear why the commander did not support the attackers – he still had at least one legion in reserve. According to Caesar, the Romans lost 746 men killed (46 centurions and 700 soldiers) and soon withdrew, attempting twice to provoke Vercingetorix into battle on the plain. From Gergovia, the Romans headed towards the territory of the Aedui. By this time, the majority of them had already joined the uprising. They slaughtered numerous Roman traders and foragers in Noviodunum of the Aedui (modern-day Nevers), seized plenty of food and money, and then set the city on fire.

Defeat at Alesia

After forcing the Romans to retreat from the besieged Gergovia, Vercingetorix was unanimously recognized as the supreme military leader at the pan-Gallic assembly in Bibracte—the capital of the Aedui tribe, the last to join the rebellion; only two tribes remained loyal to Rome (the Lingones and Remi). In the assembly at Bibracte, Vercingetorix also declared that the Gauls should continue avoiding a pitched battle, disrupting Caesar’s communications and supply routes.

Alesia, near modern-day Dijon, was chosen as the pivotal point. The Celtic leader reiterated his support for expanding the uprising into Narbonensis, dispatching his troops there. However, when the rebels sought the support of the Celts in this province, the largest tribe, the Allobroges, flatly refused to collaborate with them. Furthermore, Lucius Julius Caesar, the proconsul’s distant cousin, raised 22 cohorts of levies in the province and successfully resisted all attempts at invasion.

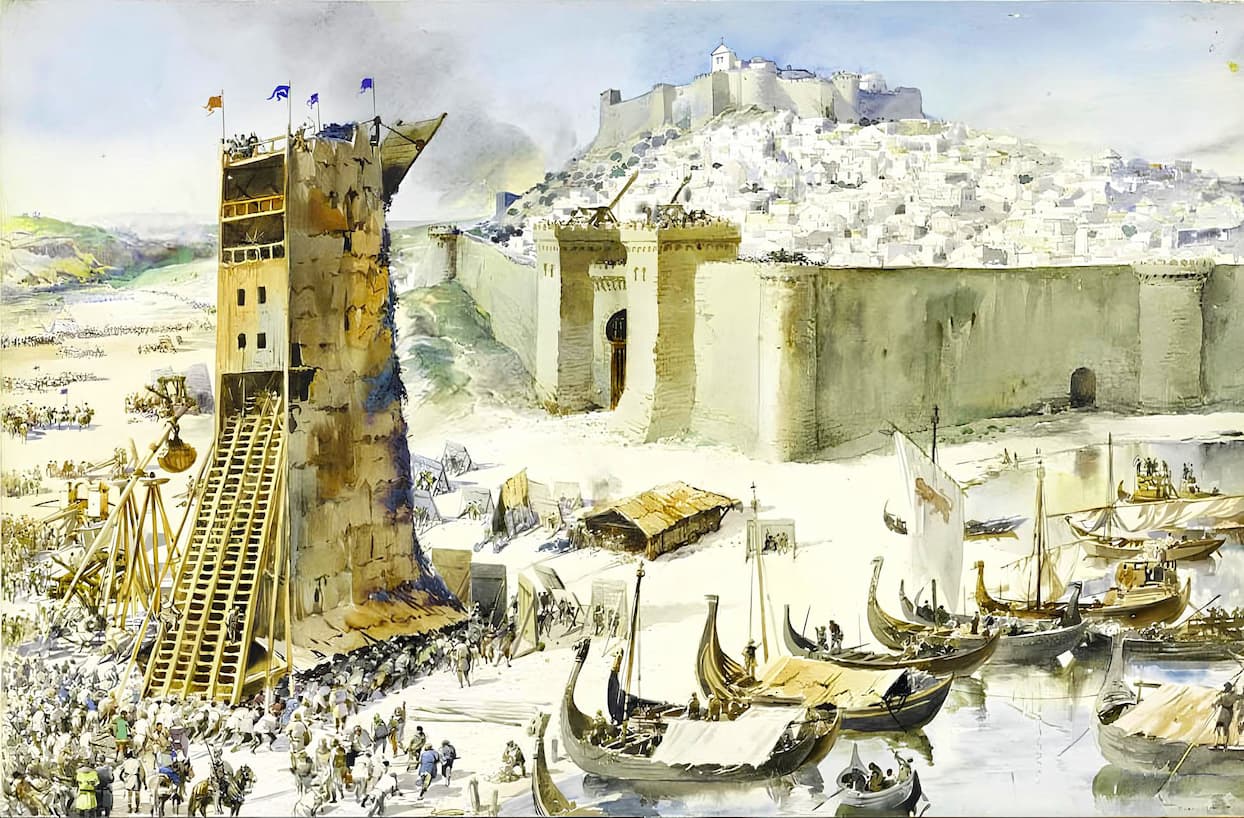

Despite their initial success, the rebels were eventually surrounded in the fortress of Alesia in central Gaul. Alesia was situated on a steep hill in the middle of a valley and was well-fortified. Vercingetorix, probably hoping to replicate the scenario that worked at Gergovia, found that the Romans instead began a systematic siege rather than attempting an assault. To achieve this, Caesar had to disperse his forces along the constructed siege walls with a total length of 11 miles (17 kilometers; according to other sources, 20, 15, or 16 kilometers).

The siege was particularly challenging due to the numerical superiority of the besieged over the besiegers: in Alesia, according to Caesar’s account, 80 thousand soldiers were sheltered. However, a more likely estimate of the besieged’s numbers is 50-60 thousand, although Napoleon Bonaparte and Hans Delbrück estimated the garrison of Alesia at only 20 thousand Gauls. The Romans, on the other hand, had either 10 war-weakened legions totaling 40 thousand soldiers or 11 legions with 70 thousand soldiers, including auxiliary forces, depending on different accounts.

The Gallic commander attempted to lift the siege by attacking the legionnaires constructing the fortifications, but the assault was repelled. Some rebel cavalry managed to break through the Roman ranks, and on Vercingetorix’s orders, spread the news of the siege throughout Gaul, urging tribes to muster armed resistance and march to Alesia. Although Vercingetorix called for assistance from other Gallic tribes, Julius Caesar organized a double ring of siege around Alesia, allowing him to break down the besieged and their allies who had come to their aid.

After all attempts to breach the Roman fortifications proved futile, the rebels surrendered due to the famine that had gripped Alesia. As food supplies neared exhaustion, and the Gauls calculated that they had enough provisions for at most a month, Vercingetorix ordered the evacuation of a multitude of women, children, and elderly from the city, although the Gaul Critoignat supposedly suggested consuming them. The majority of those forced to leave Alesia belonged to the Mandubii tribe, who had surrendered their city to Vercingetorix. However, Caesar commanded not to open the gates for them.

Although a massive Gallic force led by Commius, Viridomar, Eporredorix, and Vercassivellaunus approached Alesia at the end of September (with its strength, according to Caesar’s inflated estimate, exceeding 258 thousand people; according to Hans Delbrück, 50 thousand soldiers), the first two attempts to break through the fortifications ended in favor of the Romans. On the third day, a 60-thousand (according to Caesar’s testimony) detachment of Gauls attacked the Roman fortifications in the northwest, which were the weakest due to the difficult terrain.

Leading this force was Vercassivellaunus, Vercingetorix’s cousin. Other troops carried out diversionary attacks, hindering the proconsul from concentrating all forces to repel the main blow. The outcome of the battle at the northwest fortifications was decided by Caesar’s directed reserves, brought by Titus Labienus to the flank of 40 cohorts, and the cavalry that outflanked the enemy— the Gauls were defeated and fled.

As a result, the next day, Vercingetorix laid down his arms. Plutarch describes the surrender of the commander as follows:

“Vercingetorix, the leader of the entire war, donned the most beautiful armor, adorned his horse richly, and rode out of the gates. Circumventing the elevation on which Caesar sat, he dismounted, removed all his armor, and, sitting at Caesar’s feet, remained there until he was taken into custody to be preserved for the triumph.” — Plutarch. Caesar, 27.

Vercingetorix, among other trophies, was brought to Rome, where he spent five years in captivity in the Mamertine Prison, awaiting Caesar’s triumph. After participating in the triumphal procession in 46 BCE, he was strangled (according to other sources, died of hunger in prison).

Legacy of Vercingetorix

Napoleon Bonaparte held a low opinion of Vercingetorix and other Gallic leaders who lost in the face of repeated numerical superiority, unlike later French authors who saw the roots of French culture precisely in Roman Gaul. During the Romantic era and the increased interest in national history, the Gallic War began to be interpreted in France as the conquest of freedom-loving Gauls by foreign invaders, whom they saw as the ancestors of modern French.

In 1828, Amedée Thierry released the work “History of the Gauls,” extolling the courage of ancient Gauls in their struggle against Roman conquerors. Thanks in large part to his popular work, Vercingetorix and Brenn, the leader of the Gauls who attacked Rome in the 4th century BCE, came to be considered national heroes of France.

In 1867, despite his sympathy for the civilized Caesar as opposed to the plebeian barbarian leader, Napoleon III ordered the installation of a statue of Vercingetorix on the hill at Alesia, who was already perceived as a hero in the public consciousness. Moreover, the facial features of the Gallic leader on the monument bear a resemblance to the emperor himself.

After the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, Caesar, the enemy of all Gauls, began to be compared to Moltke and Bismarck, the siege of Alesia — with the recent siege of Paris, and Vercingetorix — with Léon Gambetta. In 1916, during World War I, historian Jules Toutain published the book “Hero and Bandit: Vercingetorix and Arminius,” in which cruel and treacherous Germans were portrayed as the eternal enemies of the Gauls.

Vercingetorix In Art

- The film “Druids” (2001) is dedicated to this episode of Roman history. Christopher Lambert played the role of Vercingetorix.

- In the film “Julius Caesar and the Conquest of Gaul” (Italy, 1962), the role was played by Rick Battaglia.

- In the film “Julius Caesar” (2002) — Heinrich Faerch.

- In the series “Rome” (2005) — Giovanni Calkano.

- In the film “Alesia, le reve d’un roi nu” (France, 2011) — Yan Tregë.

- Vercingetorix is present in Asterix comics “Asterix the Gaul” and “The Chieftain’s Shield.”

- The Brazilian group Tuatha de Danann has a song “Vercingetorix” in the album “Tingaralatingadun.”

- The international musical project Folkodia recorded the song “The Capitulation of Vercingetorix.”

- The RAC group In Tyrannos recorded the eponymous song “Vercingetorix.”

- In Viktor Pelevin’s novel “IPhuck 10,” Vercingetorix surrenders to Gaius Julius Caesar through a complex ritual, involving the violation of the Gallic leader with a carnyx in front of a silent legion.

- He is one of the available heroes of the Barbarian faction in the computer game Total War: Arena.