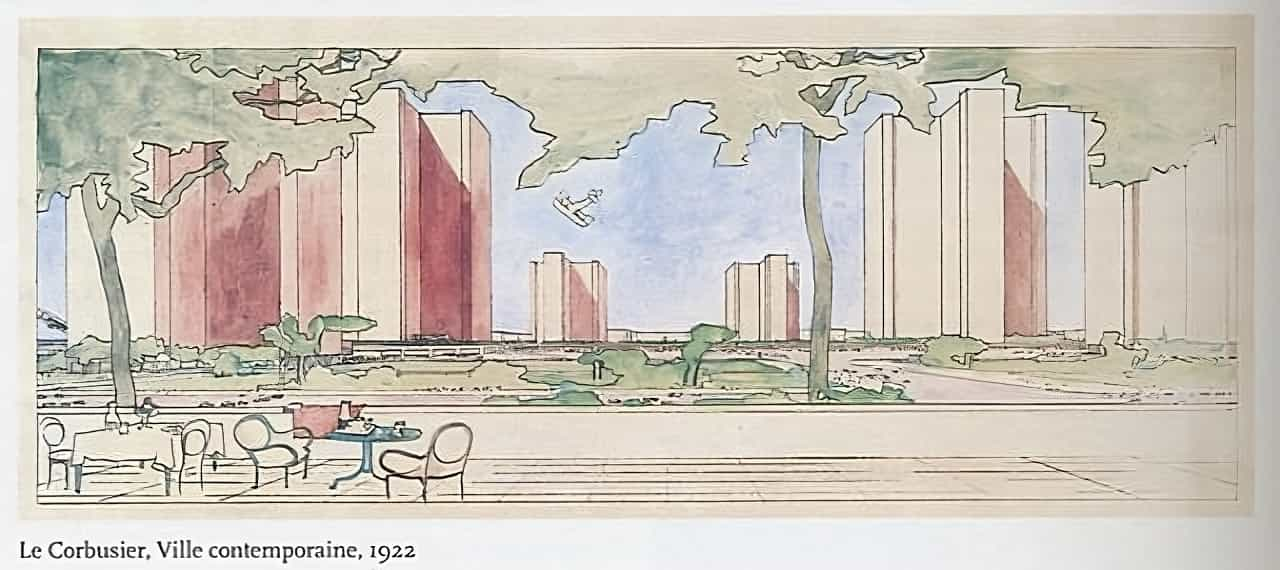

The Ville Contemporaine, or “Contemporary City,” is a visionary urban planning project created by the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier in 1922. At the time, Le Corbusier was tasked with creating the perfect city for an urban exhibition at the 1922 Autumn Salon (Salon d’Automne) in Paris. And the result was the “Modern City of Three Million People” (Ville contemporaine de trois millions d’habitants) or simply the Ville Contemporaine. His work quickly turned into a classic among visionaries.

The Historical Context of the Ville Contemporaine

After the exhibition, Le Corbusier kept working on the project, turning it from a general idea into a detailed one. Finally, he created the Ville Contemporaine. The city project was founded by Le Corbusier’s friend, the avant-garde airplane and car maker Gabriel Voisin. The project was not specific to a particular location.

In the 1980 mini TV series The Shock of the New, Robert Hughes discussed Le Corbusier’s contributions to urban design.

“…the car would abolish the human street, and possibly the human foot. Some people would have aeroplanes too. The one thing no one would have is a place to bump into each other, walk the dog, strut, one of the hundred random things that people do … being random was loathed by Le Corbusier … its inhabitants surrender their freedom of movement to the omnipresent architect.”

In 1922, Le Corbusier released a book named “Urbanism” (French: Urbanisme). Because of the detailed description of his imaginary three-million-person metropolis, his work turned into a classic among visionaries. The book continued to be published for the next 20 years. However, the traditionalists were not enthusiastic about the Ville Contemporaine. Nevertheless, the theory of urban centralism it represents has had a significant impact on the field of urban planning.

Le Corbusier advocated the urban planning theory of “urban centralism.” It was a new method of planning and construction to transform modern cities. This was in opposition to earlier theories of urban decentralism, such as the idyllic city (or pastoral city) and the organic evacuation theory. The latest iteration of satellite cities was designed with organic evacuation theory in mind. And the most stunningly gorgeous small towns in the world today are typically the result of the idyllic city hypothesis.

The Ideas Behind the Ville Contemporaine

Le Corbusier pioneered the incorporation of industrialization into urban planning. By examining the Ville Contemporaine, four primary ideas can be gleaned from Le Corbusier’s approach to city design. The first is the importance of technological change. It is for enhancing the clustering function of established metropolitan areas. The second idea is to improve traffic congestion in crowded cities. And this is achieved by erecting more “skyscrapers,” or extremely lofty structures. The idea is in line with visionary megastructures such as the Tokyo Tower of Babel, the Illinois Tower, and the X-Seed 4000.

For the third idea, the Ville Contemporaine promotes a more even spread of people and buildings throughout the city. This results in less concentration of employees and businesses in metropolitan centers. And fourth, it is necessary to create a new form of high-efficiency ground metropolitan transit system. This system includes raised roadways that are physically isolated from trains and cars.

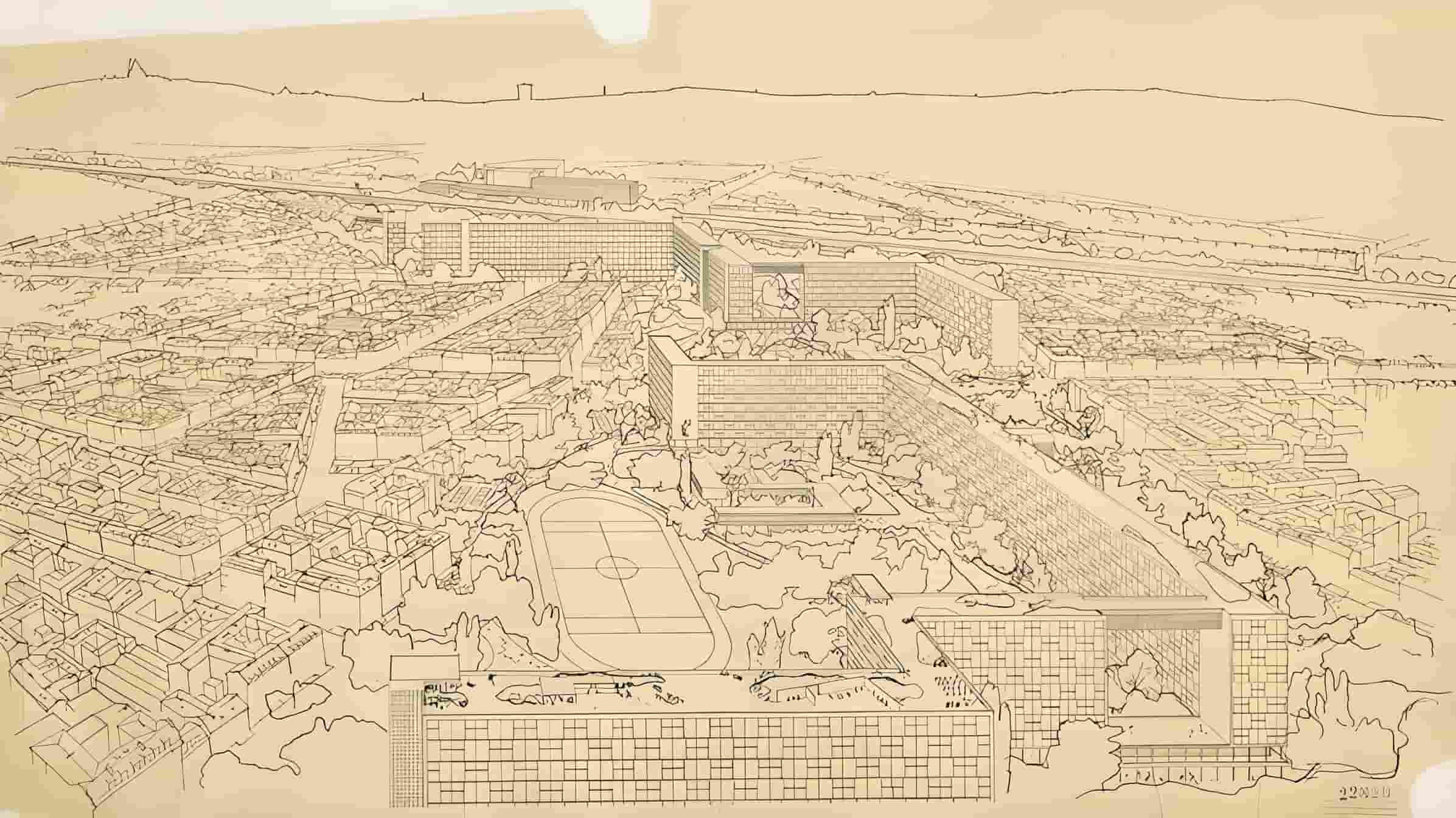

Based on the same principle as the Ville Contemporaine, Le Corbusier proposed a new plan for the rebuilding of Paris in 1925. The Plan Voisin was intended to house the offices of multinational corporations. It only consisted of a total of 16 structures but each with 60 stories. Nonetheless, the French government did not approve the proposal.

Design Features of the Ville Contemporaine

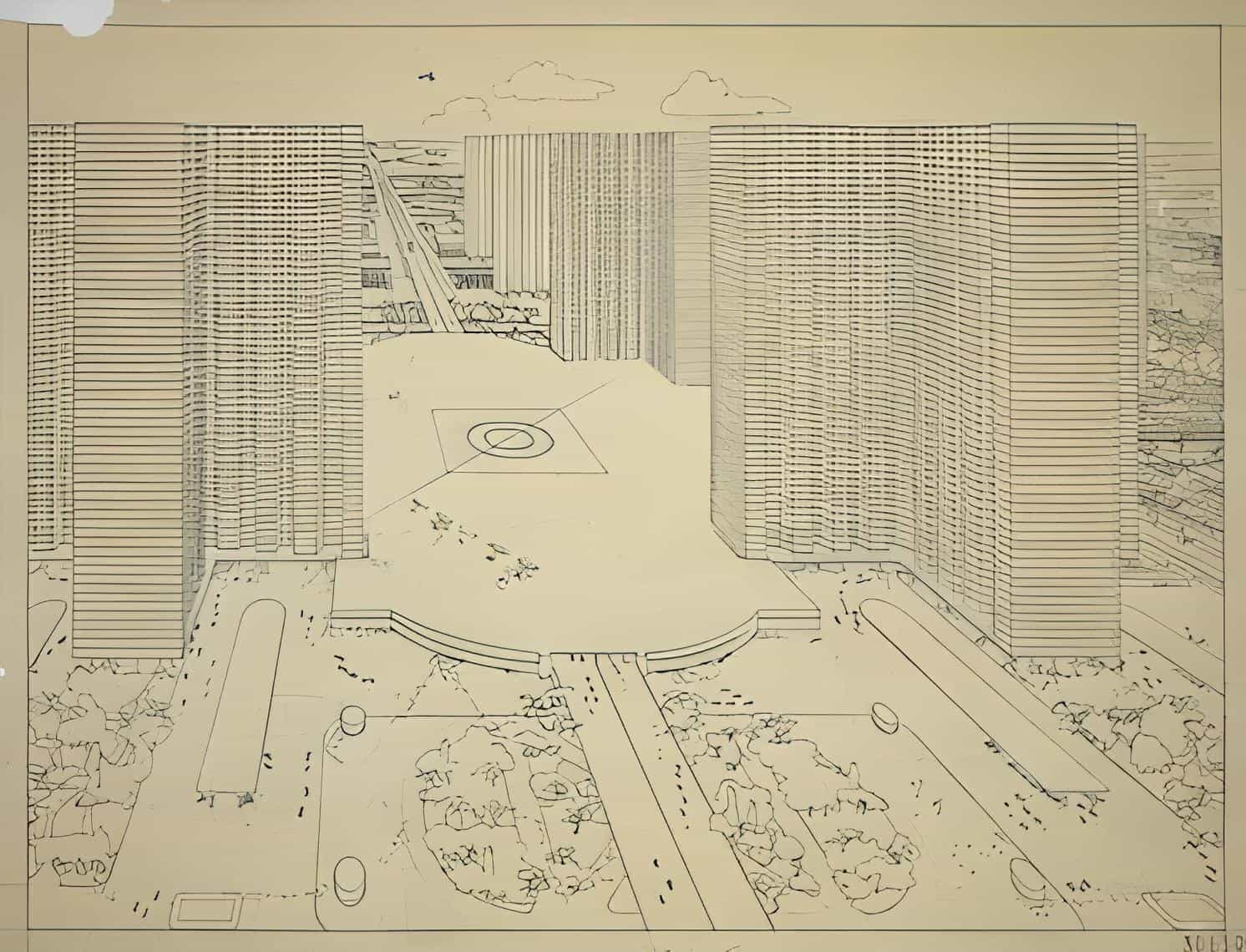

Le Corbusier’s vision for the Ville Contemporaine, with a population of 3,000,000, was to decentralize (or “evacuate”) the city center. And then raise overall density, enhance transportation, and provide green areas, sunshine, and space. The goal of Le Corbusier’s Ville Contemporaine was to make urban life as practical as possible. Le Corbusier proposed that this be done by having a central station for all cities where air taxis and buses could land. The area is also home to highway interchanges and an airport on top.

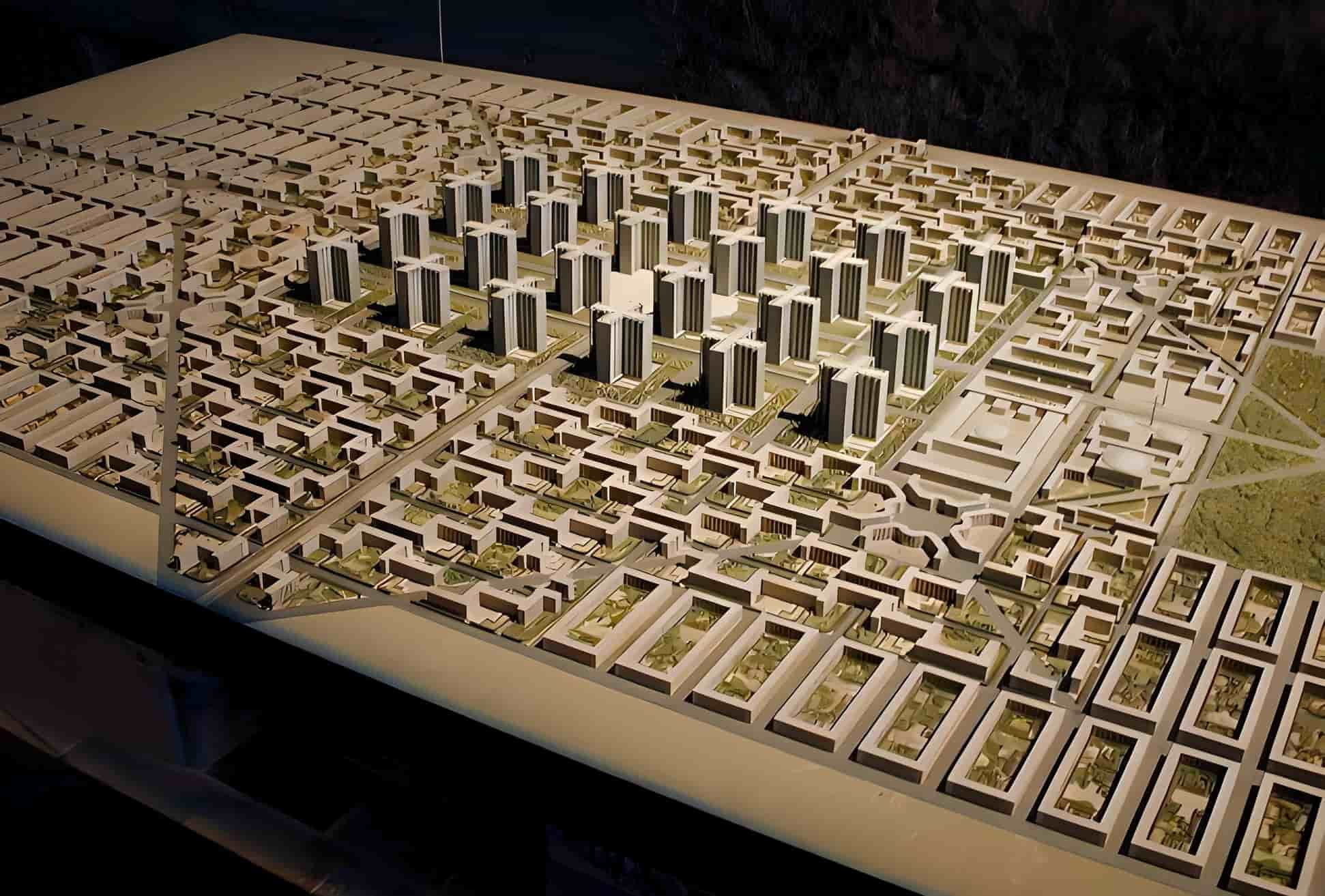

On its outskirts is a business district dominated by buildings housing anywhere from 10,000 to 50,000 people. And the Ville Contemporaine plan’s primary tenets are as follows: For its 400,000 residents, the city center is a business zone with 24 cross-shaped buildings rising 60 stories high. They are encased in steel and have curtain glass walls. Affluent people would both work and live in those towering structures.

The city’s hotels are also located in this area. Green spaces for public use are abundant among the towers of concrete and steel in this part of the contemporary city. Gardens and parks encompass an open space measuring 32,4 million ft2 (3 km2) at the base of the skyscrapers.

Outside it once more is a region of crowded living areas. They have buildings reaching a minimum of twelve stories in height and standing close together. The buildings are without gardens but instead have parks in between and additional gardening space on their roofs. Dining establishments, coffee stores, and high-end boutiques can all be found within the parks. They make a ring around the central business district.

The neighborhoods are made up of connected apartment buildings. These neighborhoods with slab-type residential buildings are home to approximately 600,000 people in the Ville Contemporaine.

On the other hand, the far reaches of the modern city have rural-style residences. They provide larger residential spaces with private lawns and buildings that are five to ten stories tall. This area is a better place to raise a family. And they are designed to house 2 million people alone. The Ville Contemporaine’s overall layout is a complex geometric arrangement of rectangular and diagonal roadways in an intertwined grid.

Every government structure is clustered together on the outskirts of this downtown area. Le Corbusier proposed elevating all parks and sidewalks on reinforced concrete pillars. This is so that vehicles could pass underneath them without impeding traffic. To reduce the need for automobiles within the urban center, the metro or railway would also run beneath these roads.