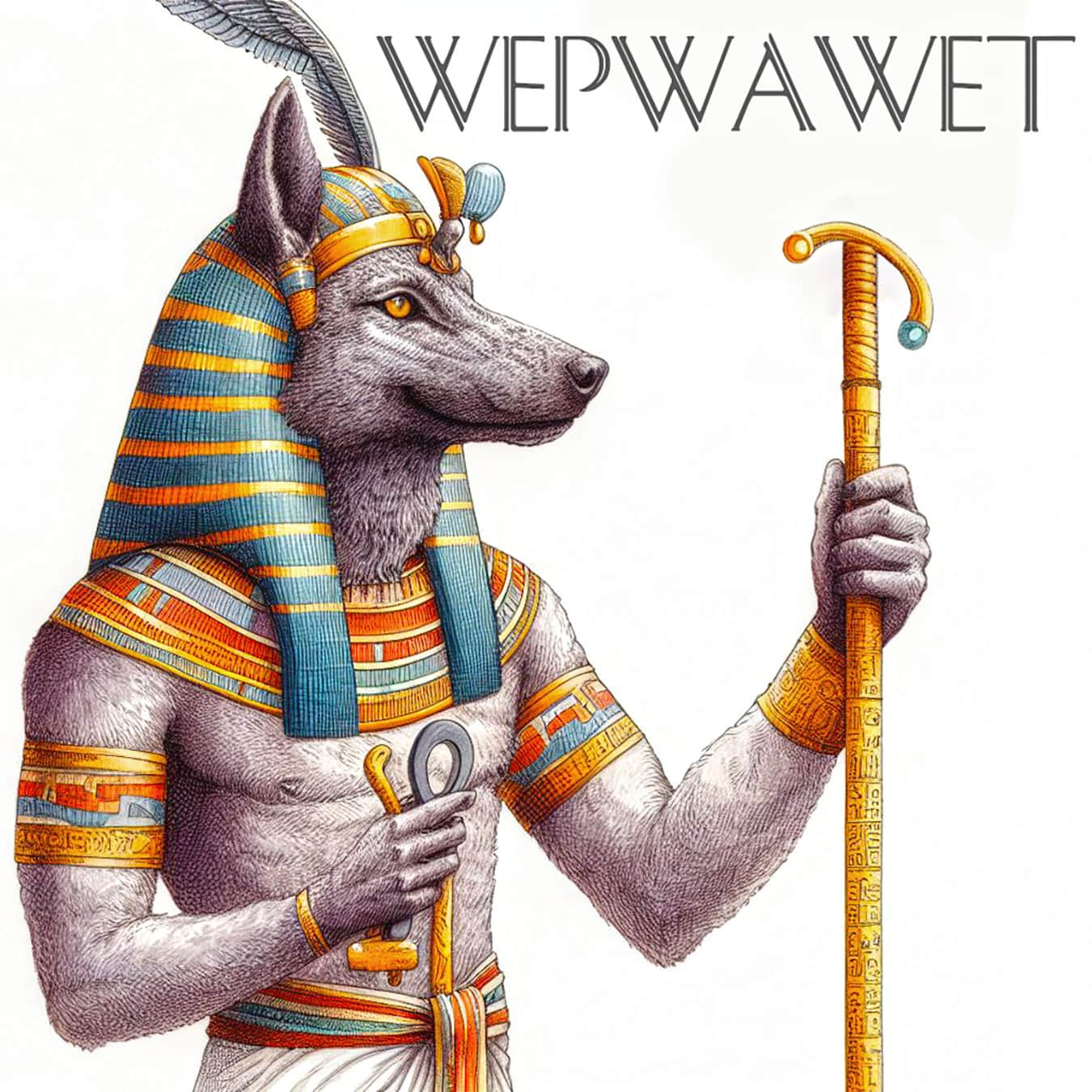

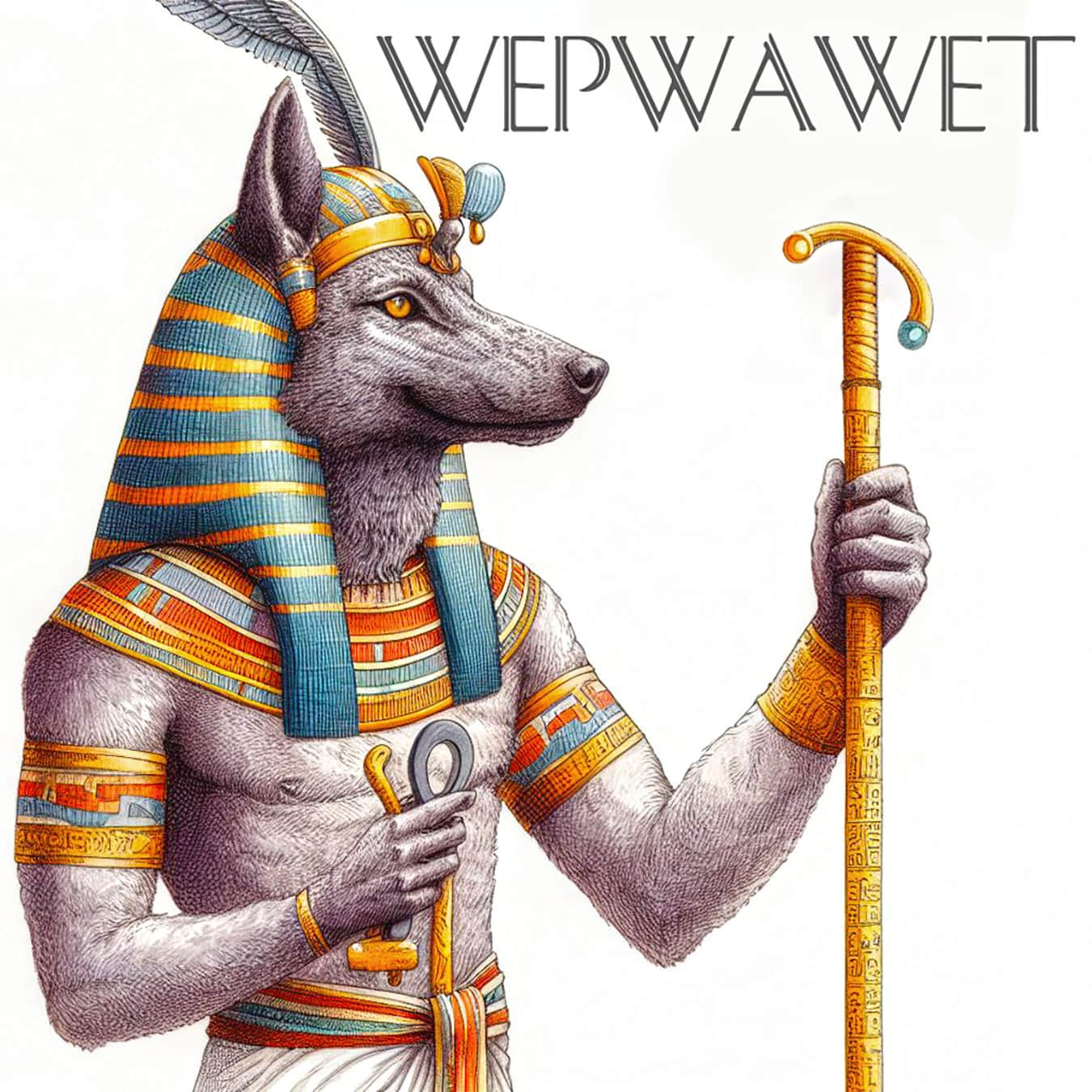

Wepwawet: An Egyptian Deity of Funerary Rites

There are almost 600 steles erected as offerings to him. The New Kingdom-era artifacts were uncovered in the Lycopolis tomb of Salakhana.

There are almost 600 steles erected as offerings to him. The New Kingdom-era artifacts were uncovered in the Lycopolis tomb of Salakhana.