What did Alexander the Great really look like? As Plutarch describes it, Lysippos‘ sculptures of Alexander were the most lifelike depictions of his appearance. Alexander personally favored this particular artist to portray his face. According to Plutarch, the tilt of his neck and the look in his eyes are two of Alexander’s distinctive features that Lysippos managed to depict. Alexander only allowed three artists to use his image in their work. These famous artists, including sculptor Lysippos, painter Apelles of Kos, and engraver Pyrogoteles, are mentioned in historical records.

But only a few copies of Lysippos’ work remain, since none of the originals have survived to the present day. According to Plutarch, Alexander was “well built,” and his height was probably around 5’4″ and 5’5″ (1.62 and 1.65 meters). He was most likely average in size. Alexander was also often portrayed with a complexion of olive or tanned colors. It is hoped that in the future, the discovery of Alexander’s tomb will provide a clearer understanding of his physical appearance.

Alexander the Great’s Most Accurate Depiction

There are numerous instances of possibly inaccurate depictions of Alexander today. For instance, some have described him as having light blond hair, while others have described him as having dark black or brown hair. This is because of an attempt to give Alexander III an idealized appearance.

No contemporaneous accounts, busts, or pictures of Alexander the Great’s look have survived to this day. This includes the sculptures of Lysippos, and all we have today are believed to be reproductions. The only descriptions of Alexander’s look are found in the writings of much later ancient historians like Arrian, Curtius, and Plutarch, but they are not very detailed or accurate at all.

Greek art differed from Roman art in that it aimed more for excellence than realism. For instance, people of Greek and Macedonian descent are not often stereotyped as having a natural blond hair color. On the other hand, Alexander was often portrayed with a complexion of olive or tanned colors, which is fitting given his Mediterranean origins and frequent open-air activities as a Macedonian general.

“The outward appearance of Alexander is best represented by the statues of him which Lysippos made. […] Apelles, however, in painting him as wielder of the thunder-bolt, did not reproduce his complexion, but made it too dark and swarthy. Whereas he [Alexander] was of a fair color, as they say, and his fairness passed into ruddiness on his breast particularly, and in his face.

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, The Life of Alexander, 1–4.

Alexander the Great’s most accurate bust is Hermes Azara. It is a Roman work that was modeled after a bronze statue created by the Greek sculptor Lysippos. The statue is believed to have been created around 330 BC. It has undergone extensive contemporary restoration, but it is considered to be representative of Lysippos’ original work and provides a useful guide for recognizing Alexander’s portraits. With his hair unkempt and his mouth parted, Lysippos captured a passionate expression of Alexander.

This pillar-shaped bust is probably one of the most accurate depictions of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). Lysippos created it in the fourth century BC, but it was remade during the Roman Empire in the first or second centuries AD. Because Lysippos was Alexander’s personal sculptor during his lifetime, historians often considered it to be the most reliable appearance of Alexander. The bust was located in Tivoli, Italy, to the east of Rome, and it is currently on display at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

It is important to note that, by entrusting Lysippos as his personal sculptor, Alexander effectively held immense authority over the representation of his image. As a result, the busts of Alexander likely reflect his desired depiction, characterized by luxurious locks, a distinctive leftward tilt of the head, and a striking appearance.

That’s why these busts may not be entirely accurate, while this facial reconstruction below may be a more realistic representation of Alexander. Prior to Alexander’s reign, Lysippos also employed the head tilt technique in sculptures of Hephaestion (c. 356-342 BC), indicating that this styling was a prevalent choice among sculptors before Alexander.

Alexander the Great’s Most Accurate Facial Reconstruction

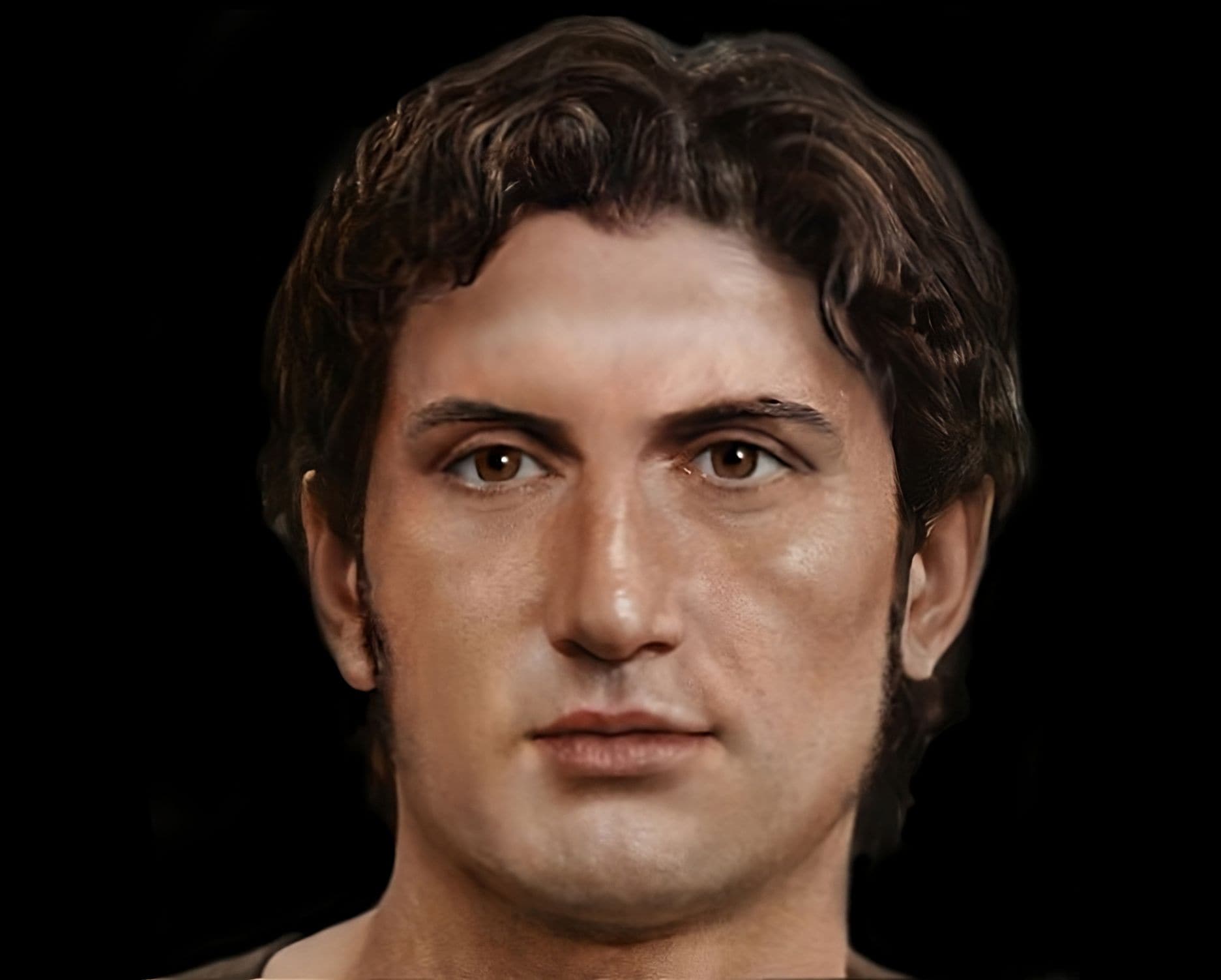

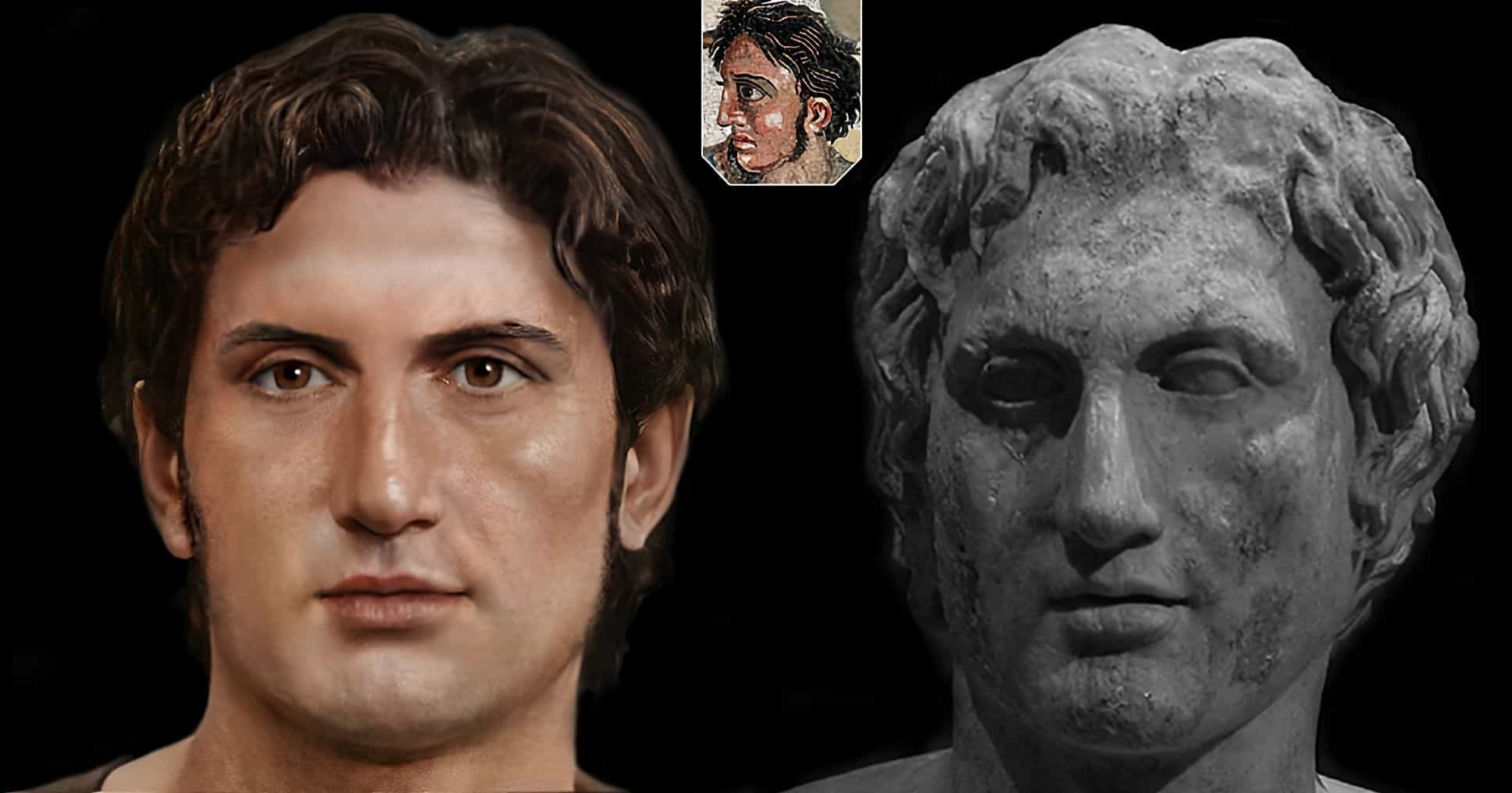

Alessandro Tomasi is a skilled digital artist from Italy who specializes in using busts, statues, and historical descriptions as reference material to ensure that his recreations are as accurate as possible. He has gained a reputation for his ability to bring these historical figures to life and has become quite popular among those interested in history and art.

This is Alexander the Great’s most accurate facial reconstruction by Tomasi. The reconstruction is based on the copied bust of Alexander created by Lysippos and also the “Alexander Mosaic,” which dates between 120 and 100 BC. Although the reconstructions are still disregarded by scholars and experts in the field, this is probably the most realistic depiction of Alexander we have today.

How Historians Mythologized Alexander the Great

As a result of historians glorifying his life and career, Alexander the Great has turned into a myth over time. Historians from the past have tended to portray Alexander in a positive light, highlighting his military victories while glossing over his faults. Alexander has been portrayed in popular culture in ways that distort the historical record as well as his physical appearance.

Around 338 AD, the first draft of the Alexander Romance was published in Ancient Greek. It has been later copied and interpreted so often that it has taken on mythical and fictitious overtones. It asserts that just like Alexander himself, his steed Bucephalus also possessed eyes of different colors (Heterochromia) and that Alexander’s arrival into the world occurred on the same day that the Temple of Artemis was demolished. Because Artemis had prioritized aiding in Alexander’s birth over preserving her temple. But Plutarch or other ancient historians do not mention Alexander’s eye colors.

Plutarch also mentions another mythologized detail of Alexander:

Moreover, that a very pleasant odor exhaled from his skin and that there was a fragrance about his mouth and all his flesh, so that his garments were filled with it, this we have read in the Memoirs of Aristoxenus.

Plutarch conveyed this detail that Alexander’s skin had a pleasant citrus aroma because of the common belief at the time that humans descended from the gods had naturally sweet-smelling skin.

The Paintings Depicting Alexander the Great

There are very few paintings of Alexander the Great that exist today; in fact, the only known examples were created many years after his death and depict an idealized version of him. The inspiration for this artwork above could be traced back to a painting by the ancient Greek master Apelles.

It was found in the House of the Vettii in Pompeii and is dated to the 1st century BC. But the issue is that many artists have “beautified” Alexander, and without a doubt, Apelles of Kos did too. That is why Plutarch explained in The Life of Alexander that “Apelles… did not reproduce his [Alexander’s] complexion, but made it too dark and swarthy.”

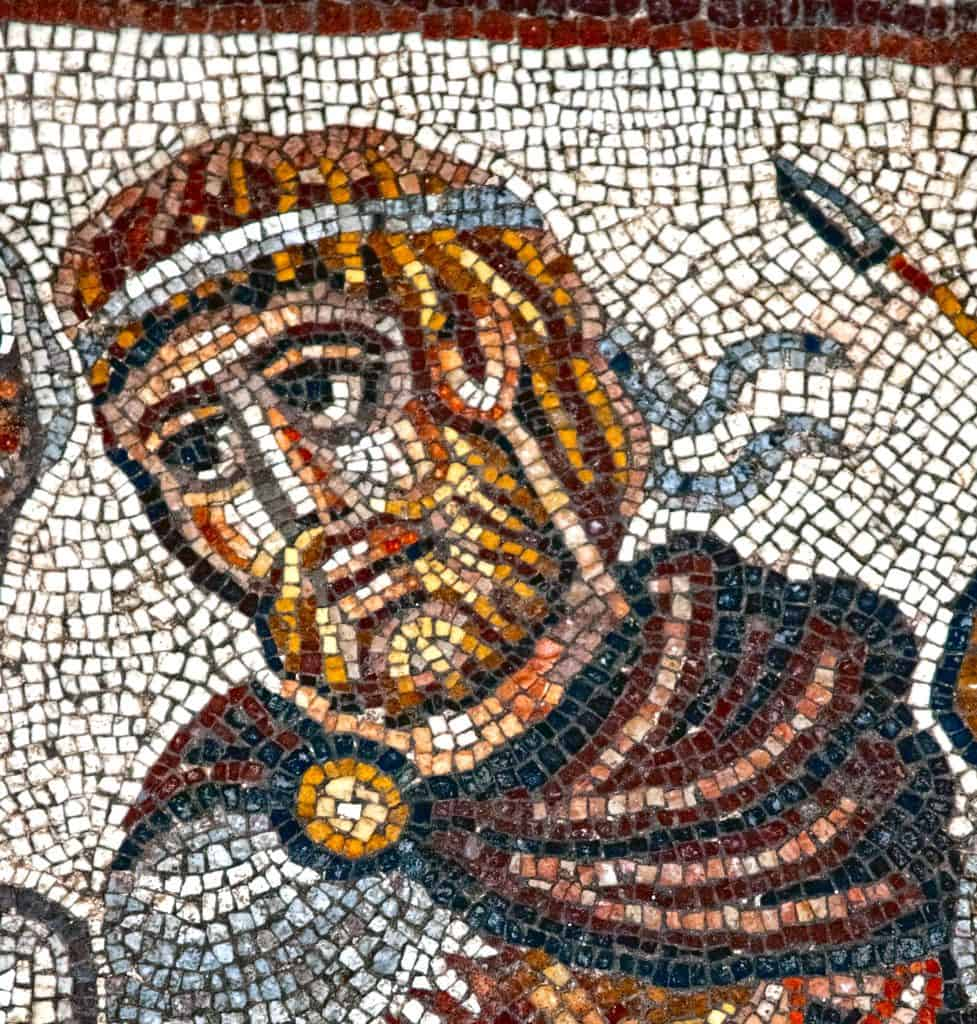

Alexander the Great was a popular subject for artists throughout the Mediterranean. In 1831, a stunning piece of art was uncovered in Pompeii—a mosaic that had adorned the floor of one of the rooms in the House of the Faun. It was among the grandest and most opulent homes in the area. This Alexander Mosaic is the most famous and probably the only authentic mosaic of the Macedonian king.

This mosaic illustration of the Battle of Issus is dated to 120 and 100 BC and is actually a reproduction of an ancient Hellenistic Greek painting, believed to have been originally crafted in Alexander’s time during the 4th century BC. The painting is thought to have been created by either Apelles or Philoxenus of Eretria, both of whom lived during Alexander’s time.

One might assume that this later copy is not of great accuracy since the mosaic is not nearly contemporary with Alexander. So, this depiction of the king could not be accurate enough. But the overall hair color and the fair skin complexion appear to be coherent in a racial sense.

There were a number of Alexander paintings made during his period that were on exhibit in historical art museums. The main building of the Forum of Augustus (which was built in 2 BC) included a collection of artworks from all around the Empire. There are probably many more paintings of Alexander the Great in the main Hellenistic cities around the world waiting to be discovered. This mosaic from a 5th-century BC synagogue in the ancient Jewish village of Huqoq in Israel is most likely a fictionalized version of Alexander the Great and shows him with blond hair and a beard. During the Roman period, the village was known as Hucuca.

Alexander the Great’s Depiction in the Coins

Silver Drachms, Silver Tetradrachms, and Gold Staters were the most common precious metal denominations among the various coins produced in Alexander the Great’s honor. However, many of the coins found today were produced in the name of Alexander by succeeding rulers.

This coin above is a depiction of Alexander the Great, who has been imagined as Herakles. The coin was minted during the time of ancient Greece, between 356 BC and 323 BC. Alexander is shown wearing the traditional lion-skin robe of Herakles, and there is a decorative border around the edge of the coin. The back side of the coin features Zeus, the King of the Gods, sitting with his eagle companion on one side and holding a staff on the other.

Located in Turkey, the city of Lampsacus in the province of Mysia served as the mint for this Alexander coin. The coin was struck around 305-281 BC, at least 18 years after the death of the king.

During his reign from 305-281 BC, Lysimachus, an old comrade and commander of Alexander the Great’s, inherited the kingdom of Thrace in northern Greece. In the early third century, he produced a series of gold and silver coins. This coin’s back depicts Alexander wearing the ram’s horn crown of the Egyptian deity Amun. The Greek inscription reads, “Of King Lysimachus,” and there is a depiction of the goddess Athena seated on the back.