Why are colds so prevalent, particularly in the winter? A recently discovered defensive system of our nasal mucosa against viral infections provides the biological rationale. Deceptive membrane-enclosed secretory vesicles (or “decoys”) are produced in large quantities in the nose to trick viruses into believing they have a suitable host cell. They are lured in and ensnared. However, if you have a cold, your body’s production of these extracellular defense vesicles reduces dramatically, rendering your immune system useless against viruses.

During the winter months, there is often an increase in respiratory infections, including the common cold, the flu, and other flu-like illnesses. Many people attribute this phenomenon to the fact that we spend more time indoors during the winter, making it more conducive for the spread of infectious diseases. Additionally, it has been shown via research that our respiratory mucous membranes’ immune defenses are impaired at lower temperatures. This means that a cold nose is an ideal breeding ground for cold viruses.

A nasal weapon: secretion globules

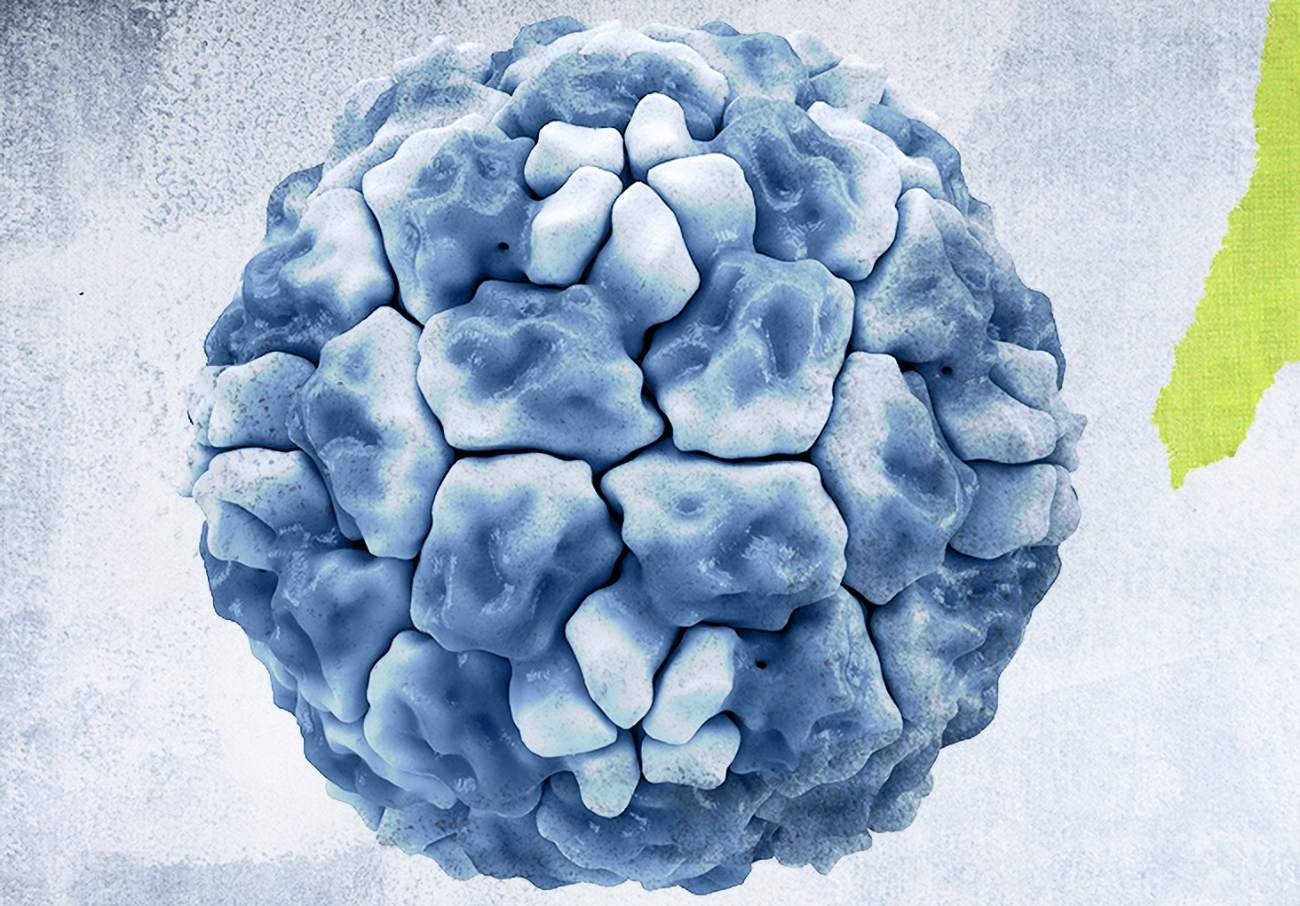

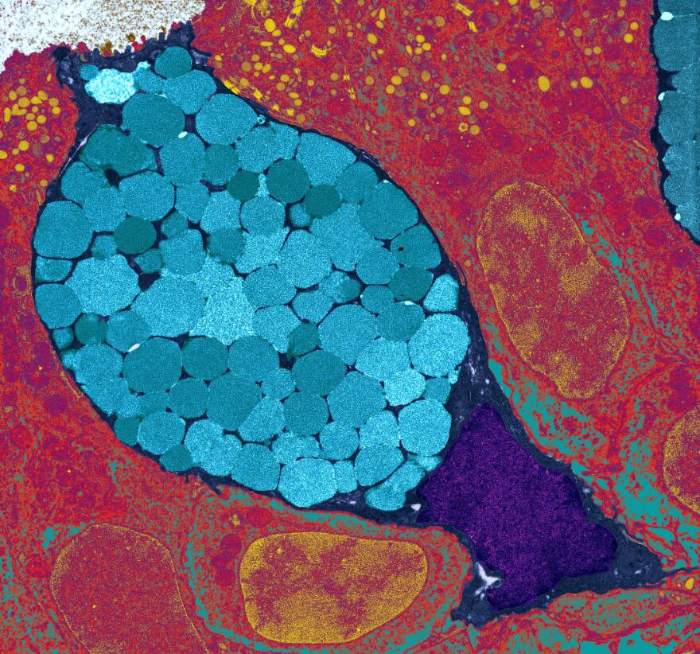

Okay, but what causes a nose to get cold? That’s precisely what Dr. Di Huang and his team at Northeastern University found. Their work focused on small, membrane-enveloped secretory globules that human nasal mucosa produces in reaction to microorganisms, which they reported in 2018. When our immune system detects pathogens, cells in the nasal mucus’ frontal lobe release large numbers of these antibacterial protein-laden vesicles.

It remained unknown, however, whether or not these vesicles were also created during viral infections, or what they were made of to combat viruses in nasal mucus. Two types of rhinoviruses and a cold coronavirus were used to infect human nasal mucosal tissue samples by Huang and his colleagues.

Decoys against viral infection

The experiments revealed that the cold viruses also stimulate the release of extracellular vesicles. However, this happens through a different signaling mechanism than in bacteria, the researchers observed. As a consequence, the membrane-enveloped secretion globules also have a distinct composition: they carry on their surface exactly the receptors that the cold viruses ordinarily employ to hook onto the mucosal cells.

That is to say, these vesicles serve as a distraction for our nose. These “host” cells really attract viruses, much as a decoy on a military plane might attract a stray missile. These viruses bind to receptors on secretory globules, where they are ensnared and neutralized. According to Huang, the more of these decoys our nose generates, the greater the possibility that viruses will be trapped by them before they can infect the mucosal cells.

Inhibition of vesicle formation by cold

Here’s where the cold comes in. To see how much of an impact cold air has on this newly found defensive mechanism, researchers chilled nasal mucosa cultures by five degrees, which is about the same as the amount our noses cool when we step outdoors into the four- to five-degree air. Actually, it came out that the amount of protective vesicles secreted by the nasal mucosa decreased by 42%, and there were less antiviral proteins on the surface of these vesicles as a result.

As a consequence, we can now explain the cyclical nature of upper respiratory tract infections using a mechanical model. This is due to the fact that our nasal mucosa’s extracellular defensive tactics are weakened by the cold weather, in addition to the fact that cold weather promotes the spread of cold viruses.

In the fight against the flu

The scientists have found a novel immunological mechanism in the nose and revealed what hinders this protection. The challenge now is figuring out how to use this natural defense mechanism to lessen the severity of common colds. Nasal sprays that trigger the production of these antiviral vesicles might be a first step.

A warm nose and a healthy immune system are our main priorities until then. So far, no effective cure for the common cold has been discovered, despite scientists’ best efforts. Creating a vaccine, for instance, is challenging due to the rapid evolution of some viruses, such as rhinoviruses. Similarly, several potential preventative measures have not advanced beyond the laboratory. Studies have demonstrated that zinc supplementation is the only way to reduce cold symptoms and minimize their duration.