Many people know what it’s like to dive headfirst into a captivating book. Sometimes fictional characters and emotions can feel completely real. But what happens in our brain when we devour page after page? How does this differ from its work during other moments of everyday life? And is there any difference at all?

These questions were partially answered by a team led by specialists from Carnegie Mellon University. They explored how we read literature using a machine learning algorithm.

How Scientists Study Brain Activity During Reading

The perception and comprehension of written text is an incredibly complex process. Early research tried to break it down into parts, focusing on each aspect separately. For instance, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), they tracked which brain structures were involved in processing a single word or sentence.

However, these strictly controlled experiments barely resembled the actual process of reading. Sentences used as stimuli for brain activity were often out of context, crafted specifically for the research. While such studies provided useful information about certain aspects of text comprehension, they did not help form a complete picture.

Machine learning specialists took a different approach. Volunteers read a chapter from an engaging novel while scientists scanned their brains. The researchers then deconstructed the brain’s functioning process. According to the scientists, they created the first integrated model in the world that shows how our brain processes written words, grammatical structures, and stories.

The Study’s Process

Researchers gathered a group of eight volunteers and recorded their brain activity using an MRI scanner as participants spent 45 minutes reading a chapter from the book Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (specifically, the episode where the characters are learning to fly on broomsticks).

In the next stage, the scientists fed the data into a computer program they had written. Their algorithm looked for patterns of brain activity that occurred when participants read specific words, grammatical constructions, names of characters, and so on. There were 195 such “story elements” in total.

The program was able to determine which part of the chapter the participant was reading based solely on brain activity. To make these conclusions, the algorithm used models of brain activity that it had learned to associate with each story element. When researchers applied all these models at once, the program was able to identify which of two passages a person was reading with 74% accuracy, which is significantly higher than random guessing.

Finally, the scientists repeated the test for each type of story element in every brain region. This helped them discover connections between them and precisely determine which brain structures process different types of information. Some results aligned with the researchers’ expectations, while others were quite surprising.

Practical Implications of the Findings

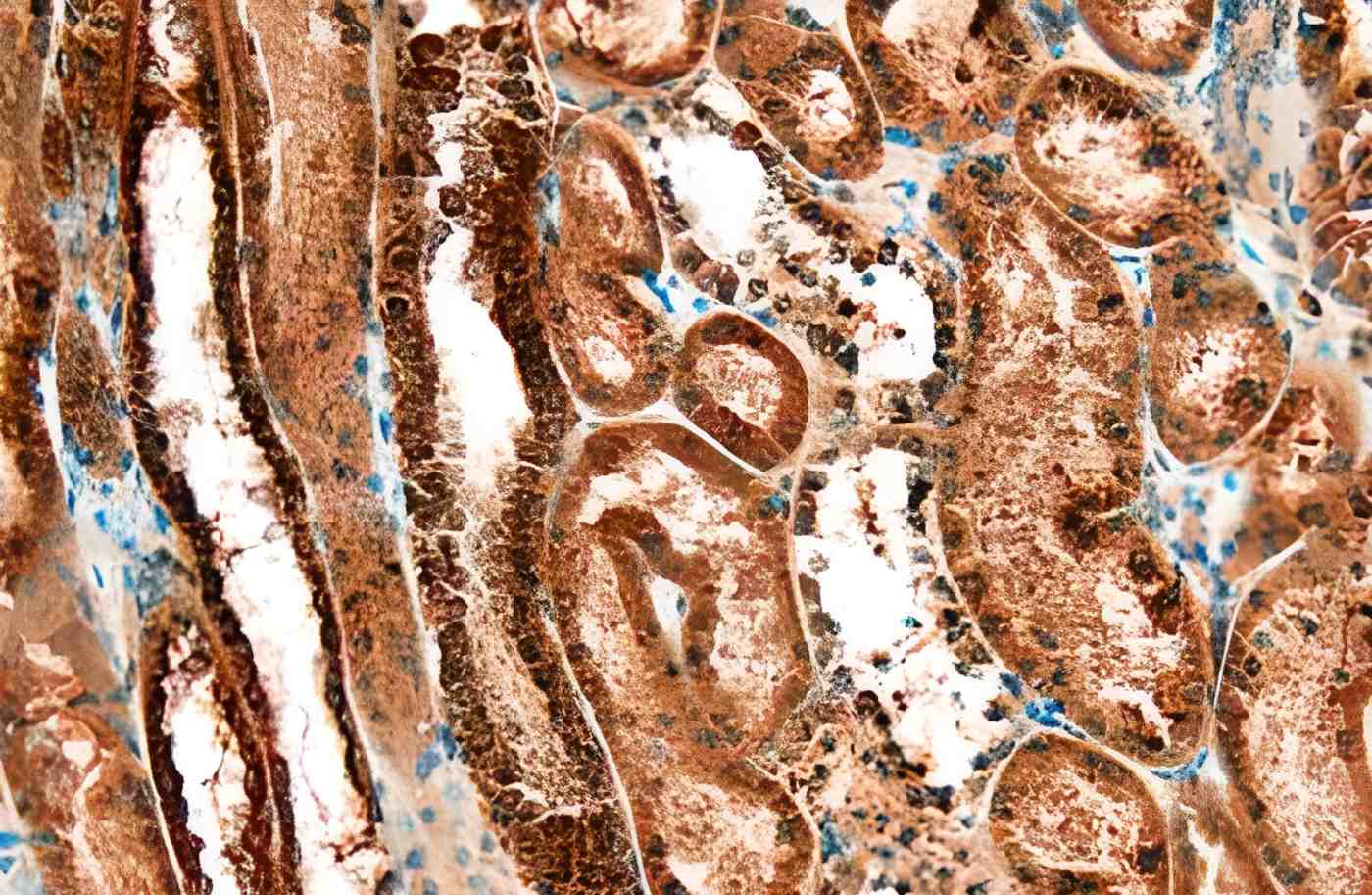

As expected, the brain processes individual words through an initial stage in the visual cortex, which handles all visual information, and then through higher-level processing areas. These include gyri in the frontal and parietal lobes, which are involved in language, speech comprehension, interpretation of text, reflection, and more. But that’s not all.

When participants read descriptions of physical movements in the book, activity in the posterior temporal lobe and angular gyrus changed.

These brain regions are involved in perceiving real-life movements.

Different characters’ personalities correlated with neuron activity in the right posterior superior and middle temporal regions. These structures are important for speech perception, visual memory, and emotions.

Dialogues were linked to the right temporoparietal junction, a brain region critical for imagining the thoughts and goals of others.

Interestingly, some of the areas listed are not even considered part of the brain’s language system.

We use them daily when interacting with the real world, and now it turns out that they also engage when we imagine the perspectives of different characters in books.

This seems to confirm the existence of a phenomenon scientists call the “narrator perspective network.” In other words, it’s a network of brain areas that allows us to “become” the character of the story we’re reading.

If these hypotheses are correct, science could be on the path not only to creating a more accurate neural model of language processing but also to better understanding how and why this process can break down.

Scientists are interested in various ways that speech perception can be disrupted. With enough data, they may be able to understand how one brain, for example, that of a person with dyslexia, works differently from any other.

Researchers hope that such diagnostic tools will one day help create individualized neurological correction methods for dyslexia and other reading disorders. If these methods prove effective, many people may find it much easier to fully immerse themselves in a good book.