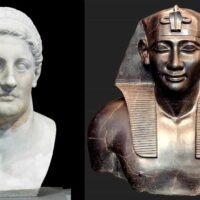

When Julius Caesar Gave Cleopatra the Throne

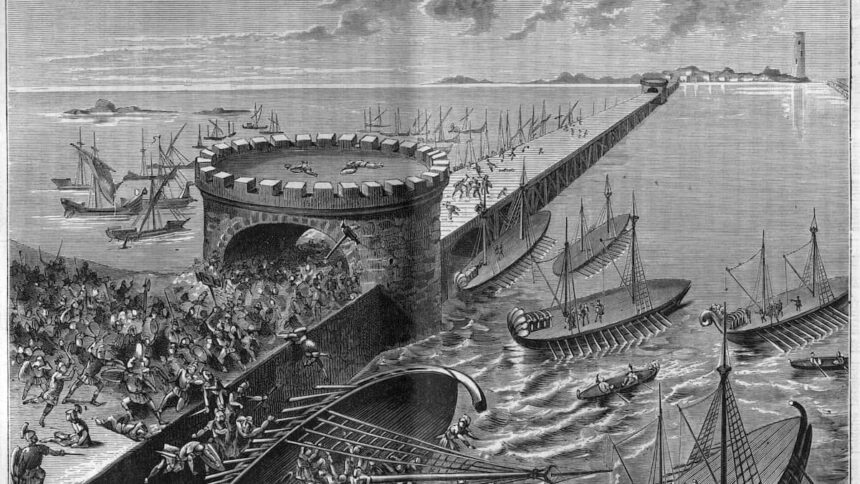

In October 48 BC, the imperator arrived in Egypt to capture his rival Pompey. He ended up staying for nine months to fight the armies of Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII. Julius Caesar nearly lost his life in battle but ultimately triumphed. Before leaving, he entrusted the kingdom to the Greco-Egyptian princess, Cleopatra.